The University cleaned up at the 1900 Summer Olympics in Paris, collecting 21 medals— 10 of them gold—in track and field events. Since then, there’s been a Penn presence at every summer games the US has participated in. On the eve of the 2012 London Games (which will make 25), here are some stories of Quaker Olympians through the decades.

By Dave Zeitlin

Illustration by Chris Sharp

Photos: University Archives

Sidebar | 2012, Too

Sidebar | Two Big Loves: The Olympics and Penn

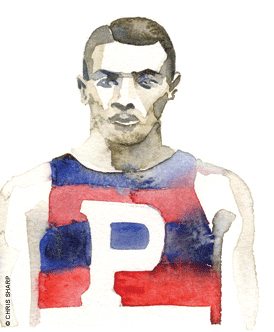

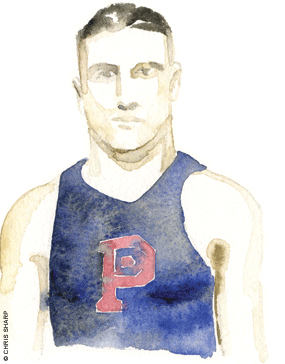

Two years after Franklin Field was built, a muscular dental student named Alvin Kraenzlein D1900 arrived in Philadelphia and made an indelible mark on the now 117-year-old stadium. The son of German immigrants, Kraenzlein could run fast and he could jump high and he did both so well that he helped the University of Pennsylvania’s track team emerge as the nation’s best. He was a bona fide athletic star at Penn, one of the first of many.

But that wasn’t all. In 1900, Kraenzlein and some of his Penn track teammates embarked on a bold voyage to Paris to compete in a new international competition: the second modern Olympics. For Penn, it was a trip that would be the start of something special.

The Olympics were much different then, with athletes competing for their colleges or clubs, instead of for their home countries as they do today. That worked out well for the Quakers, who took one of the world’s most powerful teams to Paris. Thirteen Penn track stars participated in the 1900 Olympics, collecting a total of 21 medals, 10 of which were gold. Walter Tewksbury D1899, Kraenzlein’s roommate and fellow dental student, and Irving Knott Baxter L1901 claimed a whopping five medals apiece, while Kraenzlein returned home with four gold medals, all in individual events: the 60-meter run, the 110-meter hurdles, the 200-meter hurdles, and the long jump. To this day, the only other American men to win four track and field golds at a single Olympic Games are legends Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis—and both were aided by medals in relay races.

Kraenzlein wasn’t just a Franklin Field phenomenon. He was a worldwide track sensation, enshrined forever in Olympic lore.

“He would clearly have been the outstanding athlete in the world that year if there had been a poll taken,” said Penn Relays director Dave Johnson, the University’s preeminent track and field historian. “When people speak of Jesse Owens being the first to win four Olympic gold medals, they’re actually mistaken. It was Kraenzlein who did that.”

There’s a reason Kraenzlein is sometimes overlooked when people talk about all-time great Olympians. For starters, the sport of track and field was not nearly as widespread at the turn of the 20th century as it is today, meaning there was less competition. Secondly, some of the events the Penn athletes medaled in have since been discontinued. And then there was the bizarre set of circumstances that helped Kraenzlein win the long jump, as Syracuse’s Meyer Prinstein was forbidden by his school to compete in the finals because it was held on Sunday, the religious day of rest. (Legend has it that Kraenzlein and Prinstein had an initial agreement that neither would compete on Sunday, and when Kraenzlen did anyway, Prinstein punched him in the face.)

But Penn’s wildly successful 1900 Olympics was still, according to Johnson, something the University “trumpeted quite a bit—and we have ever since.” And even as the Olympics grew from an ambitious idea to a commercialized spectacle, even as more countries participated and different events were added, even as little-known amateurs became professionals with corporate sponsors, Penn could remain proud of its sustained participation and success on the world’s athletic stage.

Excluding the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, a Penn student, coach, faculty member, or alumnus has appeared in every single Summer Olympics. (Penn may not have sent a team to Athens in 1896, Johnson reasons, because they didn’t know much about it.) Taking into account the Games that were cancelled in 1916, 1940, and 1944 due to war and the US boycott in 1980, that’s a streak of 24 consecutive Summer Olympics in which Penn has had a representative. And the streak will continue at the 2012 Olympics in London, which runs from July 27 to August 12. (See the story on page 36.)

According to an online exhibition posted by the University Archives and Records Center, Penn’s athletes have won at least 26 gold medals, 28 silver medals, and 28 bronze medals. Among the medalists are legends like Jack Kelly C’50 (who rowed in four Olympics and later became the president of the US Olympic Committee), future World War II heroes like Wilson T. Hobson W’24 and James C. Gentle W’26 (who helped the US field hockey team win its only Olympic medal, a bronze, in 1932), and longtime Penn swim coach Jack Medica (who swam to a gold and two silvers at the 1936 Games).

In all, the University of Pennsylvania has sent nearly 200 athletes, coaches, managers, doctors, and committee members to the Olympics—competing in sports that include track, rowing, swimming, wrestling, field hockey, equestrian, fencing, rugby, and yachting and representing countries ranging from Canada to Belize to Great Britain and to Greece.

To bring the Olympic experience to life, we’ve selected some compelling Penn Olympians to feature, spanning nearly 100 years of history and five different sports. Some are living and some are dead; some are men and some are women; some are black and some are white. But they all share one thing in common—carrying the flag for their country and for Penn. Here are their stories:

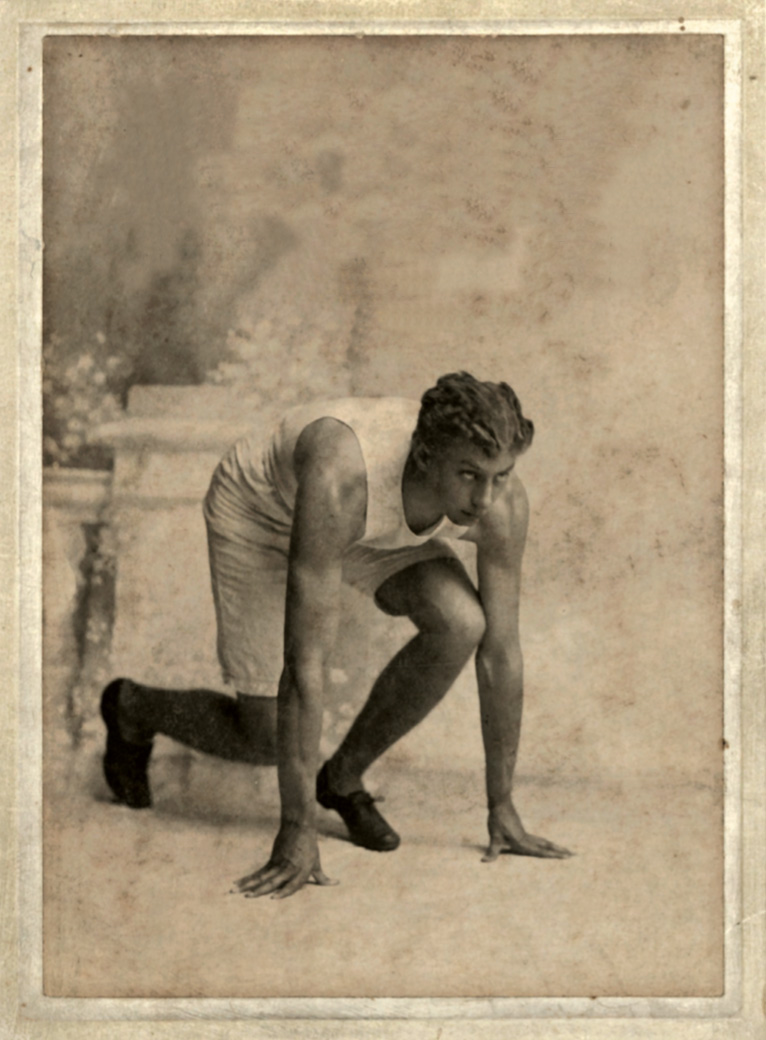

John Baxter Taylor V1908: The Pioneer of the Track

Starting in 1900 and lasting through the 1930s, Penn athletes enjoyed an incredible amount of Olympic success on the track. Among the standouts were sprinter Nate Cartmell W1908, who won four total medals at the 1904 and 1908 Olympics, and sprinter, middle-distance runner, and world record-holder Ted Meredith C1916, who captured a pair of golds in 1912.

But of all of Penn’s medal-winners from that era—or ever, for that matter— no one made as big a cultural impact as John Baxter Taylor V1908, who remains one of this country’s great, if sometimes overlooked, athletic pioneers.

A world-renowned quarter-miler, Taylor—who began his schooling at Wharton in 1903 and later enrolled in the School of Veterinary Medicine, where he graduated in 1908—was the second African American to compete in the Olympics and the first to represent his country in an international competition. Taylor then doubled down on history by becoming the first African-American to win a gold medal, when his sprint medley relay team crossed the finish line first at the 1908 Olympics in London.

Before Jack Johnson was crowned boxing’s world heavyweight champion later that year, and Jesse Owens raced to four gold medals in front of Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, and Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color barrier in 1947, there was John Taylor, the world’s most prominent black athlete.

One reason that Taylor is much less well-remembered than those pioneering figures is that he never got a chance to add to his legacy following the 1908 Olympics. On December 2, 1908, at his home on Woodland Avenue, in the shadow of Franklin Field, he died suddenly of typhoid pneumonia. Taylor was widely revered in the Penn community, and the 26-year-old’s funeral was front-page news. In an unidentified newspaper clipping, then-Penn track coach Mike Murphy called him “the nicest man he had ever had to train; he never gave any bother, worked hard, and was always on time.”

When the United States sends its predominantly black track team to London this summer, they’ll be in the same city where Taylor helped make their success possible, more than 100 years earlier. And at Penn, the first African-American to win a gold medal has certainly never been forgotten. Above his desk, Penn’s interim men’s track and field coach Robin Martin C’00 keeps two pictures: one of himself running and one of Taylor.

“He’s definitely one of my heroes,” says Martin, a black track star at Penn in the late 1990s. “He reminds me what’s possible and what’s powerful within. He prevents me from allowing mediocrity, from allowing the idea of just being okay, to creep into my head.”

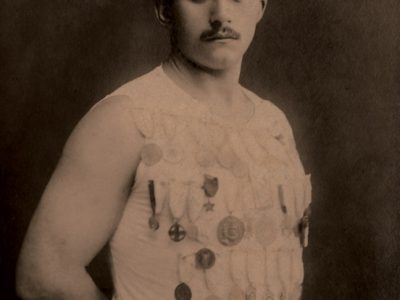

Samuel Gerson CE’20: The Peaceful Wrestler

Somewhere, perhaps in an old box in a basement, dusty and weathered, there is a copy of the 1916 South Philadelphia High School yearbook. And inside those crinkled pages, there is an entry on a graduate named Samuel Gerson, which might seem a bit harsh and, looking back on it now, also laughably ironic. “He is a crackerjack chess player,” the entry reads, “but as for his wrestling, he is only mediocre.”

After leaving South Philly High in 1916, Gerson went on to win an intercollegiate wrestling championship at Penn and an Olympic silver medal in wrestling for the United States, before using the sport to springboard a lifelong mission to foster world harmony.

We should all be so mediocre.

“He felt the Olympics was a peace movement,” one of his three children, Jack, said in an interview with the South Philadelphia Review in 1988, 16 years after his father died. “And that Olympians, because of their prominence, could promote peace, rather than war.”

Interestingly enough, his son said in the same interview, Gerson never spoke about his trip to the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, when he took home a silver medal in the featherweight class of freestyle wrestling. In fact, Gerson—who came over to the United States from Ukraine in 1895 to live with relatives in South Philadelphia—was said to have thought that he experienced prejudice because he was Jewish, which perhaps prevented him from winning the gold.

After graduating with an engineering degree from Penn, where he captained both the wrestling and chess teams, he began to wrestle against those kinds of prejudices. Following the end of World War II in 1945, Gerson staged the first Olympic reunion of its kind in the US—at the old Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia—and organized what was called “the United States Olympians.”

“In spite of obstacles, lack of funds, and social standing,” he wrote in a 1952 letter, he managed to track down past US Olympians and create groups of them in eight different American cities. The hope, he wrote in a newsletter, was that “these Olympics groups will work in unison and gather at the site of all future Olympic games to maintain good fellowship, friendship and exchange ideas of peace in a world full of disorder, disunity and belligerence.”

Looking to extend his reach, Gerson, whose day job was as an engineer, traveled to the 1960 Olympics in Rome and launched a worldwide organization, the Olympian International. Based out of Philadelphia, his home city, it began with 22 countries, a number that swelled to 36 at the 1964 Games in Tokyo. In a 1968 Pennsylvania Gazette notice, Gerson said he planned to go to Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil to continue to promote his group in even more nations, connecting people around the globe in a way few people did before the age of the Internet.

The last Olympics that Gerson attended were the 1972 Games in Munich, which was marred by a terrorist attack in which 11 Israeli athletes were killed. It’s been said that Gerson—a longtime member of Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel in Philadelphia and the founder of the Maccabi-Philadelphia Sports Association for Jewish athletes—was so distraught by the attack that it contributed to his death later that year, of a heart attack.

But his love for the Olympics lives on. Inscribed on his tombstone, in a cemetery in Delaware County, is the Olympic emblem of five rings, intertwined.

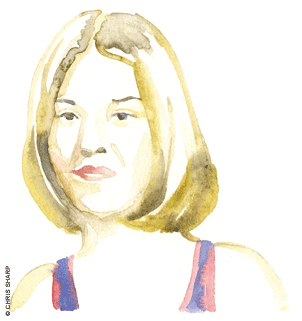

Ellie Daniel CW’74: The Swimming Superstar

When she was only 18 years old, Ellie Daniel went to the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City and returned with swimming medals of all varieties: one gold, one silver, one bronze.

In today’s world, such an accomplishment would be met with fanfare and adulation, and would almost certainly allow her to pick the college of her choice to continue swimming on scholarship—that is, if she didn’t decide to turn pro. But back then?

“Not one recruitment letter,” Daniel recalls. “Not one phone call.”

Sadly, before the advent of Title IX in 1972, which banned sex discrimination in schools, women had little traction in the way of college athletics. And not only were there no athletic scholarships available for Daniel, there were also no sponsorships for Olympic swimmers back then, which meant that just training for the Olympics caused a significant financial strain on her family.

But none of that squashed her dreams of swimming on the world’s stage—in multiple Olympic Games. It was a goal she first set when, as a wide-eyed 11-year-old, she went to a national swim meet in Philadelphia and ran around the pool to collect autographs.

“I swam for the pure love of it, and I just wanted to be the best I could be,” says Daniel, who actually didn’t learn how to swim until she was nine, after flunking beginners’ swimming lessons at least four times. “It was a very personal goal. Money had nothing to do with it.”

Following her remarkable Olympic debut in ’68—when she won gold in the medley relay, silver in the 100-meter butterfly, and bronze in the 200-meter butterfly—Daniel enrolled at Penn (the academic reputation, as well as the proximity to her home in Elkins Park in the Philadelphia suburbs, attracted her to the University) and trained with the Quakers’ men’s swim team. After two years at Penn, she took a leave of absence to live and train with other potential Olympians in Sacramento, a grueling regimen that helped her break the world record in the 200-meter butterfly four times and qualify for the 1972 Games. There, she added another medal to her collection, returning from Munich with a bronze in her marquee event, the 200 fly.

The 1972 Olympics would mark her final time swimming competitively, as Daniel decided to return to Penn, where she earned two bachelor degrees—in psychology and education—in 1974. Later, she went to law school and began working as a prosecutor with the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office in 1990. She still works there today.

“I just couldn’t do it anymore, even though I hadn’t reached my potential,” Daniel said of her athletic career. “I thought I could swim faster. But I made the goal to go to two Olympics, and I could only justify that in terms of the expense and the sacrifices my parents and brothers were making.”

Just because she retired, however, did not mean she ceased to make an impact on her sport. Three years after her final Olympic swim, Daniel testified before the President’s Commission on Olympic Sports to advocate for changes to the amateur athletic structure. That helped pave the way for the United States to start sending professionals to the Olympics, which has undoubtedly helped many athletes like Daniel achieve their dreams without the burden of finances weighing them down.

“They are truly 100 percent professionals now and that’s wonderful,” Daniel said of today’s swimming stars. “And I was one of the pioneers who fought for that.”

Anita DeFrantz L’77: The Rowing Trendsetter

Anita DeFrantz remembers staring ahead at the rough water, the waves hitting her boat from both sides, the absolute silence at the starting line, the French commands, the steely-eyed determination, the boats taking off, the eruption of sound, the pumping of arms, the East German boat pulling ahead and then the Soviets doing the same, crossing the finish line in third place, and the excitement of bringing home a bronze medal in the 1976 Olympics in Montreal in what was the first year the United States fielded an Olympic women’s rowing team.

But she also remembers the helplessness, anger, and despair she felt when she was denied the opportunity to do it again because of the United States’ boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (to protest the Soviet war in Afghanistan). In the 32 years since then, even as a prosperous career sprouted from her Olympic involvement, that feeling has not subsided.

“I’m still furious,” DeFrantz says. “It was a ridiculous thing to be done.”

A practicing lawyer at the time, DeFrantz filed a lawsuit against the boycott, which she believed to be unconstitutional. The Olympics, she reasoned, are not about political squabbles between countries. They’re about the equality of dreams and individual citizens seeking the privilege of competing for their countries, no matter the obstacles.

If anyone should know that, it’s DeFrantz. After getting a late start to her rowing career, beginning as an undergrad at Connecticut College, she returned to her native Philadelphia to go to law school at Penn. Despite her classes and schoolwork and her graveyard shift at the Philadelphia Police Department, she trained with the exclusive Vesper Boat Club, whose stated goal is “to produce Olympic champions.” That’s what she wanted to be, even if it meant not getting very much sleep and eating quick, cheap meals most days.

“It was dicey for sure,” she says. “But I was on a mission.”

When DeFrantz found out she was selected for the women’s eight crew, she immediately called her parents, who, she says, “always thought it was interesting I was rowing but were never quite sure about it.” That changed when she became an Olympian, and adding a medal was the icing on the cake—even if she and her teammates were disappointed they didn’t win gold.

“If you were looking at us [on the medal stand], we didn’t look all that happy,” DeFrantz says. “We had come to win a gold medal. But I think we knew that the odds were against us.”

Since then, DeFrantz has paved the way for many other women to proudly wear medals around their necks. Despite losing her 1980 lawsuit and missing her last opportunity to compete internationally herself, the Penn law graduate has stayed heavily involved in the Olympics, becoming the first woman and the first African-American to represent the United States on the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1986 and then the IOC’s first woman vice president in 1997. She is also president of the LA84 Foundation, which uses surplus funds from the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles to create sports program for youths.

“I feel very fortunate to have noticed these opportunities,” DeFrantz says. “Sometimes opportunities are right in front of you and you ignore them.”

As chair of the IOC’s Commission on Women and Sports, DeFrantz has made it her primary mission to create gender equality. And she proudly pumps out some statistics to show how far the Olympics have come. From 1988 to 2010, she notes, almost twice as many women competed than from 1900 to 1984. And at the 2012 London Games, about 44 percent of the athletes will be women—which represents roughly a 20 percent leap over the past 18 years. Also, for the first time in history, all of the programs will be open to both men and women this summer.

How has DeFrantz been able to spearhead so much progress?

“I’ve helped people understand,” the first women’s US Olympic rowing captain says, “that it’s the right thing to do.”

Cliff Bayer W’03 WG’03: The Fencing Jedi

It began with a lightsaber.

Long before he began clashing swords with some of the world’s best fencers, Cliff Bayer dressed up like Luke Skywalker from his favorite movie, Star Wars, and clashed (plastic) swords with his older brother Greg.

“We beat each other senseless,” Bayer says. “So our parents decided to get us into something that was a bit more productive. They found a fencing club in New York and the rest is history.”

Using the same kind of scrappiness forged by being the overmatched kid brother in duels, Bayer developed into a Jedi master with the foil (the most common of the sport’s three weapons), starring first at Riverdale Country School in the Bronx and then at the University of Pennsylvania under longtime fencing coach and three-time Olympian Dave Micahnik C’59. While at Riverdale, he won his first of four US National Championships in 1995 (becoming the youngest men’s foil champion ever) and was crowned the NCAA Foil Champion the next year during his freshman year at Penn.

Still, despite his meteoric rise in the sport, Bayer once again felt like the overmatched kid brother when, as a 19-year-old, he went to the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta as part of the US foil squad.

“I was the youngest guy on the team and I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. “To go from fencing in tournaments in high-school gyms to an event where thousands of people are screaming your name was really amazing.”

Bayer ended up finishing 34th in the individual foil competition while his team placed 10th. Immediately, he began looking four years ahead to the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, where his goal was to capitalize on the experiences from ’96 and take home a medal. To do so, however, the American star would need to unseat the typical fencing powers from Western European countries.

“At that point, Americans were really very middle-of-the-road in terms of results and reputation,” says Bayer, who took time off from Penn to train full-time leading up to the 2000 Olympics. “That was a big motivating factor for me, to really disprove a lot of those notions. That’s what would really drive me to the gym in the early morning and late at night.”

In the end, despite being one of the country’s best hopes, Bayer did not win a medal in Sydney, losing a third-round heartbreaker to eventual champion Kim Young-Ho of South Korea by a single point. The result stung, at least for a while.

“One of the great things about the Olympics—and I realize this more now that I’m retired—is that it’s less about the result,” Bayer says. “It’s more about the journey and the experience. And I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to do it twice.”

Like Daniel, Bayer made a clean break from the sport following his second Olympics. Excited to be a “full-time student” for the first-time, Bayer earned both an undergraduate and graduate degree from Wharton in 2003, before returning to his native New York to become an investment banker for UBS Securities.

These days, he doesn’t fence anymore and his old sword is buried somewhere in his parents’ house. But it doesn’t take much for him to think about his past Olympic life. Calling himself “extremely patriotic,” Bayer stops what he’s doing any time he hears the national anthem, as chills run through his body.

“One of the great things about being an Olympian is you’re always an Olympian,” Bayer says. “You always have that honor of representing your country in one of the most important and biggest sporting events in the world. It’s a real honor I take with me every day.”

Dave Zeitlin C’03 writes frequently for the Gazette and oversees the magazine’s sports blog.

SIDEBAR

2012, Too

Susan Francia C’04 G’04 eats almost 4,000 calories per day, sleeps at least eight hours per night, and spends much of the rest of her time napping, resting, or recovering. “My mom jokes that I’m a baby because I just eat and sleep,” Francia says with a laugh. “And I’m like, ‘Yeah, and row!’” Oh, right—that too. Let’s not forget the part that’s made the Penn alumna a world-class athlete and a potential two-time Olympian [“Alumni Profiles,” Nov|Dec 2008].

In mid-June, Francia, who won a gold medal as part of the women’s eight boat at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, was selected for the same eight-person boat at the 2012 Olympics. She joins a slew of other Penn students or alums that were in the mix to get to the London Games—a list that includes Tom Paradiso C’02 (rowing), Catherine Vuksich W’07 (white water slalom canoe/kayak), Matt Valenti C’07 (wrestling), Brendan McHugh C’12 (swimming), rising junior Shelby Fortin (swimming), Brian Chaput C’04 (track and field), and possibly rising junior Maalik Reynolds (track and field).

For all of them, it’s a grueling, 24-hour-per-day process that transforms their diet, sleep patterns, and daily routine in ways most people can’t even imagine … and then culminates with the pressure-packed stage of the US Olympic Trials where all of that hard work manifests itself over the course of just a couple of days.

“You’re basically living the life of a monk where you get up and train, then you recover, then you train again, then you recover again,” says Paradiso, a former Penn rower and coach, as well as a longtime member of the US National Team. “Even being in a place like Los Angeles, where there’s a nightlife and there’s beaches and there’s surfing, it’s kind of like, you can do that after. You can’t try out for the Olympics again. You can’t train for the Olympics again. But you can go surfing any time.”

All of the hard work paid huge dividends for Paradiso in 2008, when he qualified for the Beijing Olympics as a member of the US lightweight four boat. But after finishing in fourth place in the men’s double sculls finals at the USRowing Olympic Selection Events in April, Paradiso says his chances of making a return trip to the Olympics are “very, very slim.”

Following that race, Paradiso immediately began to question himself. Did he not allow enough time to prepare, having quit his job as a Penn assistant coach only last summer to begin full-time training? Did he let down his partner in the boat, Bob Duff? Will he ever be able to row the same way again after blowing out his back in 2009? Was it worth it?

“You start to wonder what else you could have done,” he says. “And in a boat where you have a partnership, it’s not an awkward situation but it’s definitely one where you feel for your partner as much as you feel for yourself, like you let him down.”

In some ways though, Paradiso says he felt “a little bit of relief” as well. Unlikely to try again for the Olympics in 2016, he can now “return to real life” and explore other options, perhaps settling in to a more permanent position on the Penn crew coaching staff.

Others like Francia aren’t ready to move on from competitive rowing just yet. Luckily, she doesn’t have to. While Paradiso, Valenti, and Vuksich didn’t place high enough at their own US Olympic Trials to earn a trip to London, Francia kept the school’s Olympic torch aflame. (Visit the sports blog at https://thepenngazette.com/category/blogs/sports-blog/ or the Gazette website, https://thepenngazette.com, for updates on all of Penn’s Olympic hopefuls and participants.)

Francia’s selection process was different than Paradiso’s because the US women’s eight boat already qualified for the Olympics by winning at last year’s World Rowing Championships. That means, as opposed to winning a race at trials, she had to be picked by a coach from among a group of women she trains with every day—which, for her, made the whole process more subjective and extra competitive.

But there’s never any shortage of motivation. All she ever needed to do was think of her last trip to the Olympics when her joy of winning a gold medal was compounded by having NBA superstars like Dwight Howard and Kobe Bryant come up to her in the Olympic Village and ask if they could hold it.

“It’s not a sacrifice for me,” says Francia, who battled back from a herniated disk and broken ribs she suffered last year. “The only sacrifice is, OK, I miss some weddings or I don’t go to a friend’s baby shower or something. But I love what I do. I wouldn’t be doing anything else.”

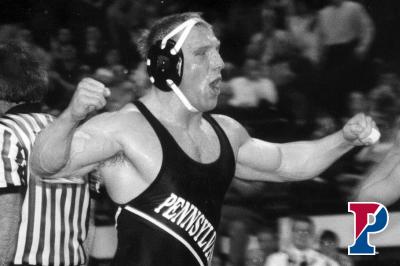

The same could be said of another Penn Quaker turned Olympic champion: Brandon Slay W’98.

One of the best wrestlers ever to go to Penn, Slay qualified for the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, and advanced to the finals of the 167 ½ pound weight class, where he lost to Germany’s Alexander Leipold. But Slay became the first wrestler from Penn ever to win a gold medal when Leipold tested positive for steroids—a feat so thrilling he later named his daughter Sydney.

Now, he’s back for more. Despite being long retired as a competitor, Slay currently works as an assistant coach for USA wrestling at the United States Olympics Training Center in Colorado Springs. And he’ll be traveling with the US freestyle wrestling team to London, where he’ll try to impart some of the lessons he learned 12 years ago.

“In the midst of all of the hoopla, all of the pandemonium of the games, you still just have to walk out there, shake hands, and wrestle,” he says. “Because I’ve been through that experience before, I think it will be beneficial for the team.”

But even knowing that, Slay still might get caught up in all of the pageantry himself. That’s because after 12 years away from the Olympics, he’s ecstatic to carry the torch for his alma mater, once again.

“I missed the grind, and I missed the journey,” Slay says. “So I decided to come back.”

—DZ

SIDEBAR

Two Big Loves: The Olympics and Penn

Almost every day, C. Robert “Bob” Paul Jr W’39 had the same routine.

He’d wake up at 5:30 a.m., put on his suit and hat, catch the 6:10 train out of Merion Station and jump on the 6:30 New York train departing from Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station. He’d sit in the smoking lounge so he could puff on his Bering cigar while he read the morning paper. After arriving at Penn Station, he’d make the mile-long walk to the old Olympic House building at 57 Park Avenue, work well into the evening and make the long commute back to his suburban Philadelphia home, where he’d retire to a table in the corner of his bedroom and do some more work—usually typing and talking on the phone, while watching a ballgame on TV and listening to another on the radio. Sometimes, on the really late nights, he’d stay in his Manhattan office, where his trusty cot beckoned.

As the first-ever director of public information and press chief for the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), where he worked from 1967 until his retirement in 1990, Paul logged so many hours for two reasons. One, he needed to, in order to keep what was then a lean organization afloat. And two, the former Penn sports information director simply loved his job. Until the day he died, in January 2011, at the age of 93 [“Obituaries,” May|June 2011], he cared deeply about the Olympics.

“Outside of his family and friends, he had two big loves: the Olympics and Penn,” says his son, Bob Paul III W’77. “He devoted his life to both of those things.”

Yes, in addition to all of Penn’s Olympians, there were also Penn graduates like Paul who further stamped the University’s legacy on the world’s foremost sporting competition. Without Paul, the Olympics might not even be where it is today. At a time when only about 10 people worked for USOC, Paul was, according to his son, “a fountain of knowledge” who not only coordinated the efforts of the media but also fielded questions from the general public. In a tribute written shortly after Paul died, his former deputy, Mike Moran, called him a “library-on-legs” and “one of the few remaining links between today’s streamlined, diverse, and powerful USOC and the tidy, patrician, Ivy League-dominated Olympic House on Park Avenue.”

“It went way beyond being in charge of publicity and communications,” Paul’s son says. “He had to wear a lot of different hats.”

Paul was certainly well suited for the job. After working as Penn’s SID from 1953 to 1961—at which time he played an integral role in the formation of the Big 5 and the Ivy League, as well as helping turn the Penn Relays into the country’s premier track and field event—and then at the Amateur Athletic Union from 1961 to 1967, Paul was a “legend in the business already,” according to Moran, when he began working for USOC.

Paul’s son remembers going with his dad to the Summer Olympics in 1968, 1972, and 1976 and seeing just how happy he was working at his press office in the Olympic Village. “It was probably like living his dream,” says the younger Paul, who worked the ’76 games with his dad, between his junior and senior years at Penn. But it was also a grind. “He went three days straight without even going to his room,” Paul’s son recalls. “It was remarkable how much he did on a shoestring budget in those early days.”

As he got older and the Olympics got bigger, Paul’s workload eventually became more manageable. In 1978, he and his co-workers moved from their headquarters at Olympic House to a sprawling complex in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where the USOC expanded to meet the ever-growing needs of its athletes and the media covering them. But until his retirement in 1990, Paul remained the go-to guy for Olympic information—so much so that his old boss, former USOC chief F. Don Miller, said at Paul’s retirement party, “Much of Bob Paul’s life has been an unstoppable ascension of Mount Olympus, and this evening, he reaches its summit. Therefore, Bob Paul’s life and dedication now define him—he is truly an Olympian.”

If he were alive today, Paul would probably scoff at the notion that he was an Olympian. Others did more, he might say, and others won medals for their country. For him, it was just good enough to be around the real Olympians, to befriend the ones who were living and research the ones who were not. His goal was to keep the torch aflame, always.

And then there was Paul’s just-as-strong connection to Penn. Told about the University’s remarkable streak of sending athletes to every Summer Olympics since 1900, Paul’s son remarks that it was probably his dad who first came up with that.

“Any fact out there about Penn Olympians he knew,” the younger Paul says. “That was the convergence of his two loves. He knew about all Olympians, but Penn Olympians was his favorite subject.”

Bob Paul’s son pauses for a few moments, thinks more about his father, and then continues, with a more wistful tone. “Penn’s got a great Olympic tie-in and my father is an example of that,” he says. “He helped bring it to life.”

—D.Z.