Dayton Duncan sees the national parks as the “Declaration of Independence applied to the landscape.” Now he and Ken Burns have made an epic movie about them.

By Samuel Hughes | Photo by Jared Leeds

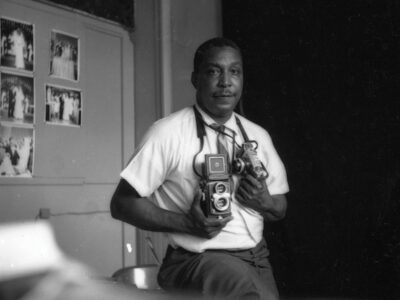

Interview with Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns

Many years later, as his son faced the mountain goats, Dayton Duncan C’71 would remember that distant time when his own parents took him to discover the national parks.

He was nine years old then, and nothing in his Iowa upbringing had prepared him for that camping trip to the touchstones of wild America: The lunar grandeur of the Badlands. The bear that stuck its head into their tent in Yellowstone. The muddy murmur of the Green River as it swirled past their sleeping bags at Dinosaur National Monument. Sunrise across Lake Jenny in Grand Teton, an image that would cause his mother’s eyes to grow misty for decades to come …

Now it was the summer of 1998, and Duncan had brought his family to Glacier, Montana’s rugged masterpiece of lake and peak and pine. Having spent some blissful days there 13 years before with his then-girlfriend, Dianne, he was returning with her and their offspring: 11-year-old Emme and eight-year-old Will. After switchbacking up the vertiginous Going-to-the-Sun Road, they crossed the Continental Divide at Logan Pass. Then, from the visitors center, he and Will set out on a two-hour hike that culminated in a near-mystical encounter with a family of mountain goats.

“In that vast amphitheater of Nature, some dim memory buried deep within the DNA of all human beings was awakened,” Duncan later recalled in an essay. As they walked back to the visitors center, father told son that, in honor of his sure-footedness, he was giving him a new name in the Native American tradition: Goat Boy.

That night, in the old Many Glacier Hotel on Swiftcurrent Lake, the elder Duncan took a peek at the journal entry Goat Boy had been furiously writing just before falling asleep. It began: THIS WAS THE MOST EXCITING DAY OF MY LIFE.

That, arguably, was the most rewarding moment of Duncan’s.

“It really was overwhelming to me, reading Will’s little hand-scrawled diary entry,” he recalls. “I told Dianne, ‘You know, this is what this trip is about.’”

Duncan is sitting on a bench in Lafayette National Park in Washington, stopping every 10 minutes or so to relight his pipe, which keeps going out because he’s too caught up in answering questions to puff on it. Behind him, past an anti-nuke demonstration and a wrought-iron fence and Pennsylvania Avenue, is the White House, shimmering soddenly in the D.C. humidity.

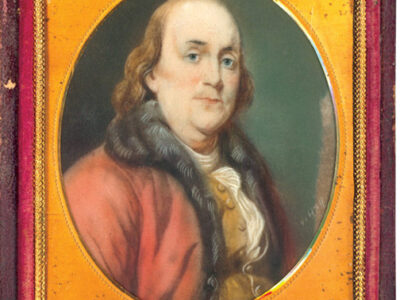

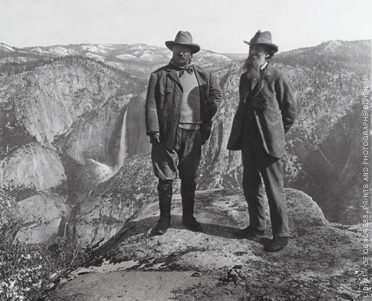

Certain occupants of that building have loomed large in the broader narrative that Duncan has been exploring. Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill creating the first national park at Yellowstone in 1872, and eight years before that, Abraham Lincoln had signed legislation protecting the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove. During a triumphant visit to Yellowstone in 1903, Theodore Roosevelt praised the “essential democracy” of the fledgling national parks, and a few weeks later spent three incandescent nights in Yosemite camping with the legendary conservationist John Muir. After the president and the high priest of the Sierras awoke their last morning covered in snow, an ecstatic Roosevelt would tell the crowds in Yosemite Valley: “This has been the grandest day of my life.” The Bull Moose would go on to become the parks’ greatest champion.

Clearly, the national parks have touched something deep inside people, whether it was the president of the United States at the beginning of the 20th century or an eight-year-old boy at the end.

“The notion that a national park is the portal to a different experience was very visceral to me,” says Duncan. “You could feel this intersection of time and place, the place being the same, which again I think is part of what parks are about. They offer you the same place, in layers of time.”

A couple days after his transformative moment in Glacier, he realized that the portal through which he had passed had led him to an idea that bordered on an imperative: “Ken and I need to do a film on the national parks.”

Roosevelt and Muir at Yosemite, 1903.

That would be Ken Burns, head of Florentine Films, arguably the nation’s most successful documentary filmmaking outfit. It’s not hard to schedule a meeting when you both live in Walpole, New Hampshire, especially when you’ve been close friends and professional collaborators since the 1980s. They had already made one very successful film—Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery (1997)—from a Duncan script, and another on the American West (1996) for which Duncan was co-writer and a consulting producer. (Duncan, the author of 10 books, also served as a consultant on Burns’ The Civil War, Jazz, and Baseball.) By 1998, the time of his national-parks epiphany, they were knee-deep in the filming of Mark Twain. But since it had taken 10 years to sell Burns on Horatio’s Drive—an entertaining romp of a tale about the first automobile road trip across the country that was still in the Florentine Films on-deck circle—he knew he had to make his best pitch.

He was certain that the story of the parks had all the elements for a classic Ken Burns film. For one thing, the national parks were a uniquely American invention; for another, their history was rife with outsized characters and unpredictable plot twists—and issues that still resonate today. That fall he decided to broach the idea.

“I wanted to come in fully loaded, with ideas and an argument for it,” Duncan recalls. “It always helps to reference things that we’ve done before. So I said, ‘We need to do a series that’s on a uniquely American idea and invention, like baseball and jazz. It springs from a democratic notion, just like All men are created equal, written by Thomas Jefferson.’ So I’ve already referenced three films now.

“Then I said, ‘The first tentative expression was in 1864 during the midst of the Civil War, and’—and I think it was right around the and that he said, ‘Yeah, let’s do this.’ So it took less than a minute. Because he got it, right from the start, and because it is right in line with some of these other major series that we’ve done.”

On the other side of Walpole, in his second-floor office in the converted barn that is Florentine Films’ headquarters, the boyish, quietly high-revving Burns concurs.

“This was right in my wheelhouse,” he says. “It is really very much about what our friendship has been about—exploring the wild spaces of America. It’s what my whole life’s work has been about, trying to understand who we are. It’s very much an American institution, and as he said, born during the Civil War. By the time you say Abraham Lincoln, you’ve got me.”

“You know, I’m very parochial,” Duncan is saying, sitting in the old clapboard house in Walpole that serves as his studio. “In the sense that the Fourth of July is, to me, the most sacred holiday on my yearly calendar. My kids got tired at an early age of listening to me read the entire Declaration of Independence on Independence Day. I believe that this is an experiment, here on this continent, that somehow came from us as a people—that we have been struggling to move forward a little bit to make it better.

“I’m also fascinated by this continent that we inhabit, and what an incredibly varied, beautiful, and huge land it is,” he adds. “Most of my adult life has been spent either exploring that notion of this experiment, or exploring the land that we inhabit—and oftentimes combining both. And [The National Parks] is an exploration of these wonderful landscapes—but it’s also an exploration of a very democratic idea expressed on the landscape.”

Duncan himself comes across as a pretty democratic expression of Iowa, where he was raised, and New Hampshire, where he has spent most of his working life. There’s a Midwestern openness about him that makes him a comfortable and heartfelt interview, both on- and off-camera, and a writerly thought process that’s been honed by political campaigns, both small-town and big-time.

“I don’t get up on a soapbox, but I have a point of view, and it often seeps through,” he allows. “And I think my involvement in politics not only ignited but informs my understanding of history.”

His first real taste of politics came after graduating from Penn, where he had majored in the unlikely field of German literature. At The KeeneSentinel in New Hampshire he earned his stripes as a reporter and editor, sharpening his edge in a column called “Wooden Nickels” that was picked up by a string of New England papers.

“We had a right-wing, somewhat lunatic governor [the late Meldrim Thomson Jr.], who would do things like call for the National Guard to be armed with nuclear weapons, or lower the flag to half-staff on Good Friday,” Duncan recalls. “Made it easy to be a political satirist.”

Thomson was defeated in the 1979 election by Hugh Gallen, who promptly called Duncan and asked him if he would consider being his press secretary.

“At first I didn’t want to, because I thought the purity of my journalism would be forever soiled,” says Duncan dryly. But he quickly realized that it would be pretty interesting to work in the State House, “trying to undo and rectify a lot of things I didn’t believe in, with a guy who believed in the things that I believed in.” Within a year he had become Gallen’s chief of staff—and a certified political junkie.

“I love politics,” he says. “I mean, I love the purpose of it. I believe in it. I like campaigns because they’re exhilarating, as well as important.”

One day he got a call from a young filmmaker from Walpole who had an assignment from the BBC to interview the governor about reviving old mill buildings and mill towns. Duncan agreed to the request, and when the time came, “this guy that looked like he was 14 years old walks in.” His name was Ken Burns.

When Burns’ first film, Brooklyn Bridge, was nominated for an Academy Award a year and a half later, he invited Gallen and Duncan to attend a special screening in Hollywood, where the governor was using the success of On Golden Pondto promote the New Hampshire Film and Television Office. A friendship took root.

Gallen died shortly before his term ended, at which point Duncan went back to writing. Neither he nor incoming Governor John Sununu wanted much to do with each other, so as an “excuse to get out of New Hampshire,” Duncan decided to take a different tack. He would retrace the Lewis and Clark Trail.

In a sense, his exploration of democratic landscapes began with Lewis and Clark, who were the first to probe the continent, at a key moment of American history. “That’s both an adventure story and a travelogue,” he says, “and it’s also a look at some possibilities that might have been, had we chosen a different path.”

While some of those paths might have led to a more peaceful relationship with the original inhabitants of the continent, Duncan takes a nuanced view of that history.

“Some historians are more interested in saying, ‘Well, the history of the West is one unmitigated disaster after another wrought by white people,’” he says. “That’s the antithesis of what I was probably raised on as a young child, which was this glorious, triumphant march of civilization across the continent. Well, neither of [those views] is right.”

But politics wasn’t through with him yet, and as he was writing a magazine piece about the explorers, he got a call from Walter Mondale’s presidential campaign asking him to be its deputy press secretary. The next 16 months were spent crisscrossing the country with Mondale, who lost the 1984 election in a landslide.

Around that time he and Dianne moved to Walpole, where he reconnected with Burns, whose second daughter was about the same age as the Duncans’ Emme. It turned out that the two men had a lot in common.

“At the dinner table, I would start telling an excited story about Lewis and Clark, and my family would be rolling their eyes, and he’d be excited,” recalls Duncan. “And he’d start telling an excited story about Huey Long, and his family would roll their eyes. We learned that we both read the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July. So we realized that we had both a shared interest in storytelling, and in American history, and a belief in the purposes of our country, and democracy.”

Burns even helped with the reporting for Duncan’s second book, Grass Roots: One Year in the Life of the New Hampshire Presidential Primary (1991), in which Duncan followed a volunteer from each of the presidential campaigns for the year leading up to the New Hampshire primary of 1988.

By the time he had finished his research for that book, he had signed on as national press secretary for the Dukakis campaign. (“My job was to say, with a straight face, ‘No, he doesn’t look ridiculous,’” he says, adding that some reporters took to grading his performances on an Olympic scale of one to 10, depending on the difficulty of the task.) The election results weren’t any better this time.

“After ruining two good Democrats,” he says, “then the party got together and said, ‘If we can just get Dayton to stay out of this and go back to writing, maybe we can win the White House’—which they promptly did in ’92.”

By then he had expanded his magazine piece about Lewis and Clark into a book, Out West: An American Journey. In retracing the route of the Corps of Discovery in the mid-1980s, he met up with a raft of colorful characters. One was Gerard Baker, a Hidatsa Indian who was then serving as district ranger at the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Park North Unit in the Badlands.

“One afternoon this guy shows up in an old Volkswagen bug, and he’s researching a magazine article about the Lewis and Clark expedition,” recalls Baker, now superintendent of Mt. Rushmore National Park. “Usually I’m kind of standoffish, but this guy immediately got into where I was at from a historical standpoint. We kind of spoke the same language. In fact, I liked him so doggone much that he babysat for my kids.

“He asked a lot of good questions,” Baker adds. “His interest was not just skin-deep. It was in his heart.”

Baker invited Duncan out to a sweat lodge, even though in those days he was “pretty closed to non-Indians doing that.” Later, when a bison escaped the park’s boundaries and Baker was forced to shoot it, he invited his guest to help with the butchering—and to partake of the raw liver. Duncan accepted the invitation.

“You go first,” Baker says, in what has become the wry gesture of hospitality. “It’ll give you some of the buffalo’s strength.” He watches intently as I chew the slice of liver: warm, a little crunchy, and surprisingly sweet and strong tasting.

Baker also suggested that his guest spend a night in an earth lodge in the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site near Stanton, North Dakota, where the Hidatsa were living when the Corps of Discovery wintered in 1804-05. To make the experience more authentic (and help his visitor survive the sub-zero blizzard blowing in), Baker provided Duncan with five buffalo robes—then pulled out his own bedding, a down-filled Eddie Bauer sleeping bag good to 20-below, and informed his guest that it was the responsibility of the person with the most buffalo robes to keep the fire going all night.

“Dayton was a true brother, because I got along with him immediately, which means I gave him a bad time from the start,” says Baker, who makes an appearance in The National Parks. “I took him back home, among my relatives, and oh, they’d be merciless on him. Tease and tease, and he’d laugh and tease back.” Baker’s family later adopted Duncan into their clan.

The personal connection was enhanced by the fact that Duncan had read and thought a lot about the U.S. government’s history with the native peoples it was displacing.

“There were a lot of things that happened between the tribes and the government, and he had a really good understanding of that,” says Baker. “He was so open and honest. We had some really, really good discussions. [Out West] is actually a pretty damn good history book.”

“What Dayton combines is a kind of reporter’s ear for details and a good story with a historian’s rigor for scholarship,” says Burns. “And then there’s a new sort of x-factor, which is the personal. He’s a really emotional person, and he feels these things as much as he thinks them and sees them and hears them. That combines to make the writing not only well rounded, but to make his overall approach incredibly humanistic.”

Nowhere is that more evident than at the end of Lewis and Clark, when Duncan, speaking on-camera, describes the mental breakdown and final days of Meriwether Lewis. When Duncan finally says, eyes brimming, “and then he shot himself,” it’s an extraordinarily moving moment.

“With the death of Meriwether Lewis, I was talking about the suicide of a guy who is a friend of mine,” he says. “I don’t want to sound too Twilight Zone here, but I got to know him pretty well over the long course of studying him, and went to all the places that he did. And I can put myself there at Grinder’s Stand, and can feel the isolation that he felt, of things crowding in around him—and understand his desire for his best friend, William Clark, to be there at that hour of need, and realize that he wasn’t going to. And it’s a very emotional thing.”

Duncan recently declined an invitation from the Lewis and Clark Trail Foundation to speak at Grinder’s Stand on the 200th anniversary of Lewis’ death. “I just can’t,” he says simply. “Maybe I got to know him too well, or something. But he is a friend, and when he dies, he’s taking part of me with him.”

“Dayton is the Yellowstone National Park of human beings—things bubble up from the surface all the time,” says Burns. “He feels these stories very intensely, and this is a story he knew and loved for more than a decade. But there were many other times in the film where he began to tear up, and we just kept that off-camera—as we’ve done now in The National Parks. And you’ll see there are some incredibly moving parts as well.”

Every now and then, when Duncan and a Florentine Films crew had been up until midnight for the fourth long summer day in a row, shooting in some wild corner of Montana or Alaska, knowing that they had to get up again a few hours later and wait for the sunrise, he would light his pipe and say quietly: “Does anybody have to remind the rest of us that we’re actually being paid to be here?”

“My job requires me to take a topic that I’m already interested in, and learn everything I can about it,” he says. “Read everything about it. Meet the people who know the most about it. Go to the places that are important to those stories, then do research, and then return with a film crew. And my job requires me as a writer to write.

“And then my job requires me to work with a talented team of editors and my best friend, who just happens to be the best documentary filmmaker in America. So I have the best job in America—I truly believe that. And on this one it was particularly true, because my job required me to go to all 58 of the national parks—and many of them many different times in different seasons.”

Over a six-year span they shot 800 rolls—146 hours—of film, collected some 13,000 still images from a vast array of archival sources, and conducted 50 interviews. Since Duncan is the producer on this film as well as the writer, he’s responsible for a lot more than just the words.

“As a producer, what makes up for the headaches is the fact that you get to make a lot of decisions that, if you were just the writer, you wouldn’t get to make,” he says. “So I do get involved in music; I do get involved in who we are interviewing; I do get involved with the film trips, of where we go, of being able to tell the camera crew, ‘Let’s not concentrate on this; over here is where we want to be.’

“But it would be hard for me to produce a film I didn’t write, because ‘In the beginning was the Word,’ as the Bible says. And in the films that Ken makes, that we make together, the Word gets a lot more attention than in many other films.”

That very deliberate, Word-driven style, he acknowledges, isn’t for everybody.

“We get accused sometimes of being fuddy-duddy and slow, because we don’t have a lot of quick edits and such,” he acknowledges. “We believe that by having that extra time, if you’re looking at an image while you’re listening to John Muir, you’re more likely to absorb what this guy’s got to say to you than if you’d carved that shot into 25 shots.”

In Burns’ view, it’s not so much that he and Duncan are on the same wavelength as it is a matter of complementary talents and sensibilities.

“I bring certain things, he brings other things, and they work really well” together, says Burns. “He’s an incredibly great writer and producer, and he’s dogged in his determination to get it right and do the right thing. That’s invaluable, particularly nowadays as I’ve moved to working on several things at once. To know that there’s somebody like Dayton on the ground, on a particular project, is to be able to sleep at night.”

The National Parks: America’s Best Idea is both a six-part, 12-hour film airing on PBS this month and a companion book published by Alfred A. Knopf. It’s not much of an exaggeration to call the film a hymn, and the book a lavishly illustrated hymnal. Those who received the wild’s call, like John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt—and Dayton Duncan—emerged with a wilderness-revering passion that borders on the religious.

“This is the morning of creation,” John Muir was heard to cry out during an early Sierra Club outing. “The whole thing is beginning now! The mountains are singing together.”

As with most Burns/Duncan collaborations, there are plenty of outsized characters, whose stories are presented warts and all. (Well, maybe there aren’t any warts on Muir, unless you’re put off by the fact that he once drank the steeped juice of sequoia cones in order to make himself “more tree-like and sequoical.”)

“We’re old-fashioned historical-narrative storytellers,” says Duncan. “We very much believe that you start here and you move through time. And we want to bring people to life because that’s how history actually occurs—with real people, not knowing how things are going to turn out, making decisions and doing things.”

Take the second episode, which begins with a young New York politician reading a newspaper article about the destruction of the buffalo herds and becoming so upset about their looming extinction that he jumped on a train headed west. His name was Theodore Roosevelt, and his goal on that trip was to bag a buffalo before the species became extinct.

“Teddy Roosevelt is just a force of nature, and a great exemplar of how nobody is stereotypical,” says Duncan, whose film on Mark Twain cast the president in a slightly less favorable light. “You love him as you’d love a boisterous nephew, knowing that he also breaks the china. As [historian] Clay Jenkinson says in our film, he has a little suspicion of anybody who wasn’t willing to kill a quadruped.”

While Roosevelt never lost his love of hunting, “there was an evolution in his own mind about what conservation was about, partly under the tutelage of George Bird Grinnell,” adds Duncan, referring to the conservationist and Audubon Society founder. “Grinnell helped steer him towards a larger view of conservation, and the result was the greatest president for the national parks and conservation you could ever imagine.”

Ask Burns about the film’s wide range of compelling characters, and he plays down the big names.

“It’s funny—when people bring it up they always say, ‘Oh, Teddy Roosevelt,’” he says. “And I say, ‘Yes, and he’s fantastic, but he’s one part of our second of six episodes.’ Or maybe you’ll have someone who knows about John Muir, or John D. Rockefeller [Jr]. But what was so wonderful, and surprising for us, was the discovery—without any kind of politically correct attempt to root it out—that this was just an amazingly diverse story, that is black, and brown, and red, and yellow, and female, and unknown, as much as it is male, and white, and well-known. And that makes for some good storytelling.” (An ironic example of that diversity is the fact that Yosemite and Sequoia national parks were overseen by the Buffalo Soldiers in the first decade of the 20th century—“when more African Americans were lynched than at any other time in our history,” as Burns points out.)

A sampling of characters includes:

• Virginia McClurg, the champion of Mesa Verde, who at the last minute changed her tack from preserving the ruins as a national park to having it become a “women’s park run by her very exclusive women’s organization,” says Duncan. “At the final moment, she couldn’t quite get to it becoming a national park, and everybody’s park, instead of just her park.”

• George Melendez Wright, a naturalist who in the late 1920s undertook—and funded out of his own pocket—a wildlife survey of the parks, which would provide the data and recommendations for putting the wild back in wildlife.

“We take it for granted today, but it wasn’t always that way,” Duncan points out. “When I was visiting Yellowstone you could stop and feed the bears. There were no wolves, because they’d all been killed.”

• U.S. Representative John F. Lacey of Iowa, author of some of the most important environmental legislation in the nation’s history.

“Lacey was a very conservative Republican, but he had a number of radical ideas,” says Duncan. “He saved the birds of the Everglades from being slaughtered. He wrote the law that gave protection to the buffalo and the elk, and the natural features of Yellowstone. And this conservative Republican authored the Antiquities Act, which ceded to the president of the United States an authority to act unilaterally that no Congress in its right mind anymore would ever do. It became the most important tool for conservation in our history, one that activist presidents have used to the horror of Congress, and to the outrage of local politicians—at the Grand Canyon with Theodore Roosevelt, at the Tetons with Franklin Roosevelt, in Alaska with Jimmy Carter, with Bill Clinton in the southern part of Utah.”

• George Bird Grinnell, the conservationist and Audubon Society founder who led the fight to create Glacier National Park. (He also teamed up with General Phil Sheridan, who had become so disgusted by the slaughter of Yellowstone’s wildlife that he dispatched a troop of cavalry to oversee the park—a “temporary” measure that lasted some 30 years.)

• Marjory Stoneman Douglas, the Miami journalist and nature writer who led the fight to save Biscayne Bay.

• Stephen Mather, the dynamic marketing executive who pestered Interior Secretary Franklin Lane (a college classmate) about the parks’ deteriorating condition until Lane told him: “If you don’t like the way the parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself.” Mather spent a great deal of his own money improving the parks, lobbied for the creation of a National Parks Service, and became its first director.

There are others, of course, ranging from hardscrabble Civilian Conservation Corps workers who built roads and planted trees during the Depression to early Studebaker-driving park visitors to some amazingly poetic park rangers.

All those stories “show a wide range of the kind of people who fell in love with these places,” Burns adds. “This is not just noblesse oblige; this is not just the province of the idle rich, but in fact a story of Americans from every stripe who fell in love with the place, and then worked very, very hard to set it aside for people they don’t know—meaning us.”

“If you boil it all down, the story behind each national park is that somebody says, ‘Wow—what a wonderful place. We ought to save it,’” notes Duncan. “Over time that could become a fairly boring, repetitive thing—except that each place is different, and each person is different.”

Not every character in The National Parks is a hero, which is just as well. Too much nobility and sequoia juice could be cloying. The doppelganger of Teddy Roosevelt, for example, is Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service and two-time governor of Pennsylvania. Though he professionalized the Forest Service, he took a utilitarian view of natural resources—that they should be developed and used, not simply set aside for people to enjoy. That strain of the American character has vied with the preservationist for control over the nation’s wild spaces, and the tension between the two camps—and others—is with us still.

“The tensions are not just, ‘Will the park get created or not?’” says Duncan. “We like to say it’s the Declaration of Independence applied to the landscape, and that very notion sets in motion tensions. If it’s open for everybody, if everybody’s co-owner, can there be rules of what they can do? Are we saving it just for this generation, or for generations yet unborn? If it’s for everyone for all time, then what do we allow? Is it the scenery that we’re preserving, or is there something more?”

Those who want to create a national park have often been at loggerheads with local people who don’t want to relinquish control of the land to the federal government, he points out. Yet over time, that local opposition has often morphed into a grudging approval.

“We have several of those stories, not only historical but in our lifetime,” says Duncan. “Someone who fought and fought against the expansion of Grand Teton National Park as a politician and then, on camera, says he’s glad he lost the battle. Someone in Alaska testifying against the ‘Carter Monuments,’ as those national parks were called, and then on camera saying, ‘Well, it turned out it’s been good for us.’”

Oddly enough, some of the most nakedly commercial interests ended up helping the parks’ cause.

“John Muir was an eloquent person, but the reason that those early parks were created was not his eloquence; it was because the railroad lobby was working the halls of Congress,” Duncan points out. “They thought, ‘Here’s a scenic attraction that will help our ridership,’ and eventually they said, ‘and maybe we can control what goes on inside the park and make even more money.’”

Every issue facing the parks today has a precedent in the past, Duncan adds. “The Army, when it was running Yosemite and Sequoia national parks and there was a problem of poaching, started confiscating people’s guns when they came in. This was long before this latest uproar about guns in national parks became an issue.”

The millions of people who visit the national parks each year encompass a wide range of recreational preferences, ranging from backcountry hikers to those who want what Duncan calls “the windshield experience.” And he is adamant that both styles should be respected.

“I’ve stood at viewpoints and watched a busload of people get off, and thought to myself, ‘The most exercise those 50 people are going to have this year is getting off that tour bus and walking the 25 yards into the beautiful scenic view and say, ‘Wow, isn’t that something,’ turn around, and get back on their bus. And that’s easy to caricature. But those people, nonetheless, will have been touched by that experience. And when somebody says, ‘They’re thinking of building a dam in the Grand Canyon,’ they’ll say, ‘Don’t you let them do that!’ And they have as legitimate a stake as the person who’s going to do the two-week backcountry, hard-core experience where they can be by themselves in nature. It belongs to all of us.”

“What is this, a Phish concert?” asked a passerby. His confusion was understandable. The line at the Bellows Falls Opera House this past July 1 was already a block and a half long, and the doors wouldn’t open for another half-hour. The sold-out event featured a special screening of excerpts from The National Parks and a Q & A session afterward with Duncan and Burns. Since Bellows Falls, Vermont, is just across the Connecticut River from Walpole, and since the proceeds were earmarked for the Walpole Historical Society and the Student Conservation Association (which sends student volunteers to work in national parks around the country), the filmmakers weren’t exactly stumbling into enemy territory. And indeed, when the excerpts end—the gorgeous shots of frost-bearded bison in Yellowstone and molten lava snaking down the black rock of Hawaii’s Volcanoes National Park, the articulate interviews with historians and park rangers, the archival footage of presidents and early visitors—the audience responds with a prolonged standing ovation.

Similar reactions have occurred at some other preliminary screenings around the country. “People come to us and say, ‘How can we help?’ and ‘How do we give money?’ says David Barna, chief of public affairs for the National Park Service, who thinks the film (which he calls “stunning”) will provide a significant boost to attendance.

“The park service gets about 275 million visitors a year,” Barna says. “That number fluctuates some from year to year, but this could easily push us over the 300 million mark.”

Such a bump would not be without precedent. Burns tells his Bellows Falls audience how, after The Civil War aired on PBS in 1990, he walked a battlefield at Gettysburg with the park superintendant. At one point, the superintendent leaned down to pick up a candy wrapper and said dryly, “This is all your fault.”

“There is nothing Dayton and I would like more,” Burns added puckishly, “than to have every superintendent in every park in the country angry with us.”

This past March, the National Park Service showed how it really felt. During a ceremony at the Department of the Interior auditorium, acting director Dan Wenk read citations announcing that Duncan and Burns had been chosen to be made honorary park rangers (a very select group, by the way). After praising his work in researching and producing The National Parks, which provides Americans with an “opportunity to reflect on the significance and value of our national parks, the public lands that we collectively own,” Wenk announced that Duncan had “demonstrated the highest and best qualities of the park ranger-interpreter.” He then presented him with one of the park service’s distinctive ranger hats.

Duncan doesn’t attempt to hide his feelings about that honor.

“When I’m at home, if I get cranky, Dianne says, ‘Go put the ranger hat on. Because you’re never in a bad mood when you’re wearing your ranger hat.’”