Ken Burns reflects on the filmic portrayal of historical heroes.

“A story is the editing of human experience,” Ken Burns observed to Penn Interim President Wendell Pritchett Gr’97 during the 2022 David and Lyn Silfen University Forum in April. “‘Honey, how was your day?’ does not begin, ‘I backed slowly down the driveway, avoiding the garbage can at the curb…,’” the documentary filmmaker continued. “We edit human experience. Everybody does, whether you’re making fiction or fact-based stuff.”

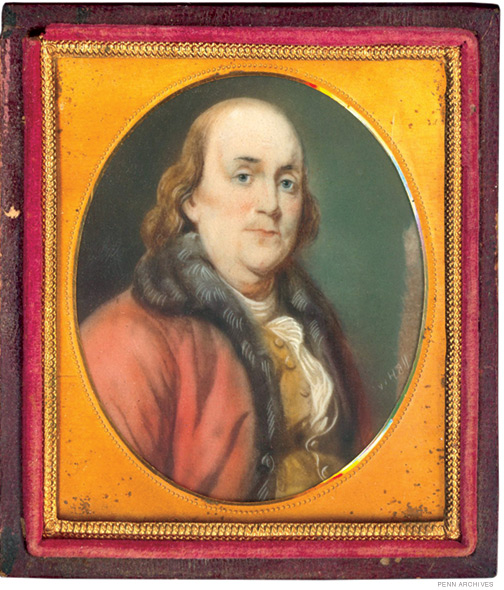

Burns, who came to Irvine Auditorium ahead of his turn as this year’s Penn Commencement speaker, engaged in a wide-ranging conversation about his latest film: the two-part, four-hour Benjamin Franklin for PBS. His conversation with Pritchett took prompts from screened excerpts stamped with the director’s characteristic style—slow pans over archival images interspersed with curated commentary from a handful of historians, ranging from popular biographer Walter Isaacson to Erica Armstrong Dunbar C’94, a scholar of early US and African American history [“Profiles,” May|Jun 2017].

The film, which received funding from the University of Pennsylvania via the Better Angels Society, endeavors to situate Franklin’s complexities within a familiar frame: a view of the American experience bending ever toward redemption. “Franklin was pretty simple in his moral code,” Isaacson intones in the first minute. “He was driven by a desire to pour forth benefits for the common good. But there’s a lot in Benjamin Franklin that makes you flinch. And we see Franklin not as a perfect person, but somebody evolving to see if he could become more perfect.”

The documentary does not shy away from the ways its subject reflected or even exemplified the anti-Black racism that suffused 18th-century America. “We have so fair an opportunity, by excluding all Blacks and Tawnys, of increasing the lovely White and Red,” we hear Franklin proclaim (as voiced by actor Mandy Patinkin). “But perhaps I am partial to the complexion of my country.” To whom the country truly belonged, and to what and whom contemporary Americans can credit for the evolution of its social contract, remain subjects of lively debate among historians. But few would dispute the significance of Franklin, whose claim upon a “quintessentially American” life draws sustenance from areas as diverse as his outsized influence on early American print culture, to his variegated support of and late-life opposition to slavery, to a genius for common-good innovation that ran from the many inventions for which he never sought patent exclusivity to his pioneering formation of mutual-aid societies like the Philadelphia Library Company and the volunteer Union Fire Company.

During the conversation, Burns explained his approach to portraying “heroes” in film, tying it to a neon sign hanging in his editing room that reads it’s complicated. His remarks have been edited for length and clarity. —TP

“In my business, if a scene is working, you don’t want to touch it. And I put that sign up—it’s in cursive and it’s lower case: it’s complicated—just to remind people that we do a better service when we find out new information and have to destabilize a pretty good scene. Because it’s always worthwhile. Maybe it’s no longer the great scene that it was. But maybe the adjacent scenes are improved by that. The whole thing is better for tolerating that complexity.

Let’s just think about heroes. We lament that we don’t have any heroes. But what is a hero, the Greeks would tell us, but a negotiation between a person’s very obvious strengths and their flaws? And the negotiation—which is sometimes a war between those things—is what defines heroism. Not perfection. So Achilles had his heel and his hubris to go along with his great strengths. The best way I know to explain it is through a story I recently heard about I. F. Stone, the muckraking progressive journalist and historian. A student of his said, ‘How could he possibly admire Thomas Jefferson?’ And he said: Because history—meaning everything—history is tragedy, not melodrama. In melodrama all villains are perfectly villainous, and all heroes are perfectly virtuous. But that’s not the way life is. And if you attend to tragedy—none of us are getting out of here alive, which is the first and essential point—then you’ve got a chance to do something.

And that’s complicated. Wynton Marsalis, in our jazz film, stunned me, because I felt he had just spoken directly to my soul when he said, ‘Sometimes a thing and the opposite of a thing are true at the same time.’ And you have to be able to hold those competing things at the same time and understand them. You can’t be married if you don’t get that. You can’t be a parent if you don’t get that. You can’t be a good friend. And I think that you can’t be wise.”