A new documentary probes the achievements—and betrayals—of an iconic civil rights photojournalist.

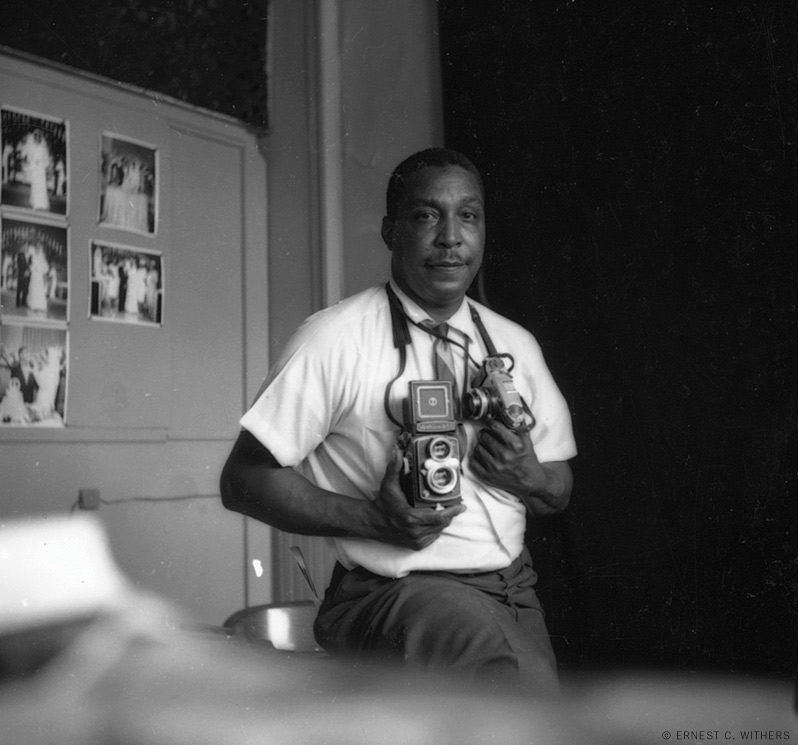

“Pictures Tell the Story.” That was the business slogan of Ernest Withers, the nominal subject of The Picture Taker, a new documentary film now streaming on PBS. Withers was a legendary Memphis-based photographer whose pictures of the leaders and events of the civil rights movement helped cement that history in the public consciousness. His photos indeed tell those stories—but the slogan came to have another, hidden, meaning as well.

After his death in 2007 at age 85, Withers was revealed to have doubled as an FBI informant, sharing many of his photographs—along with information about the people in them—with his FBI handler. A journalist at the Memphis Commercial Appeal discovered Withers’ identity while working on a related investigation and exposed him in a 2010 series in that newspaper. FBI records secured by the paper through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) confirmed he had been a paid informant for nearly two decades beginning in the early 1960s. The Memphis community, Withers’ family, and civil rights advocates have struggled to reconcile these seemingly disparate identities.

The Picture Taker is directed and produced by Emmy and Peabody Award winner Phil Bertelsen, along with producer Lise Yasui C’77—whose short documentary Family Gathering, about the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, was nominated for an Academy Award in 1989.

The Withers film project was initiated by St. Clair Bourne, who profiled several African American cultural leaders. But Bourne died in 2007, just a year after beginning production—and before Withers’ death and the revelation about his double life.

Bertelsen was asked to step in to complete the work that Bourne had begun. Withers took nearly 2 million photographs: in addition to covering the civil rights movement, he chronicled the lives of Black families and social events in Memphis, captured the Beale Street music scene, and celebrated the Memphis Negro League baseball team. Bourne’s vision, prior to the exposé, might have simply been an account of Withers’ remarkable career.

And then the revelations came out. “A complete bombshell,” says Bertelsen. “Questions were raised about his legacy, his photos, the movement—was he part of a plot to kill Martin Luther King?—literally all these doubts. The film project became much more compelling.”

Bertelsen and Yasui became friends more than 30 years ago while both were working at a PBS member television station in Philadelphia. Six years ago, intensely involved in other film and TV projects, Bertelsen asked Yasui to come on as a creative producer to help finish The Picture Taker. It would prove to be a prescient move.

“Before anything about the FBI came to light, I decided I would tell the story of the civil rights movement through this photographer,” says Bertelsen. “I never left that idea; it just got complicated by the FBI revelations. Lise understood on a personal level the impact of government overreach. Her perspective helped shape the story into something much more comprehensive.”

In Family Gathering, Yasui told the story of her grandfather, Masuo Yasui, a leader in Oregon’s Japanese American community who was arrested by the FBI within days of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Classified as a “potentially dangerous enemy alien,” he was confined for over four years in a special Department of Justice camp, part of the system of internment camps that imprisoned 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. As revealed in FBI files, investigators interpreted Masuo’s acts of Japanese community support as evidence of a plot to undermine the government.

“Researchers have since found evidence that the government’s own investigators knew the Japanese Americans weren’t a threat,” says Yasui. “When Phil described the Withers film to me, I knew from experience that there was probably more to the story than simply the enigma of Withers as an informant. The FBI’s agenda in using him as one had to be explored.”

The exploration ultimately involved thousands of documents and photographs, plus interviews with more than two dozen people, most of whom knew Withers personally: civil rights leaders, local Black community members, entertainers, and Withers’ family, among others.

As the lead researcher on the project, Yasui reviewed many of the 7,000 FBI documents related to Withers, including reports secured through two FOIA requests she initiated. “It was fascinating to read the files,” she says. “You don’t always get what you want, but the answers sometimes come from cross-referencing reports. For instance, the FOIA reports we secured were redacted in different places than the reports the Memphis newspaper suit obtained, divulging key information. I also found references to Withers in the John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. FBI files that were recently unlocked.”

Through the lens of Withers’ career, the film tells another complex story. Retired FBI agent Avery Rollins recalls in the film that during the Cold War—which intersected with the rise of the civil rights movement in the 1950s—the FBI believed that Soviet agents were trying to penetrate and take over civil rights groups. Informants were crucial in identifying suspected infiltrators, and Rollins observes that Withers’ FBI number, ME338-R, indicates that there were 337 prior informants in Memphis (“ME”) alone.

But the value of an informant’s report must be “taken with a grain of salt,” as Tim Weiner, an authority on the FBI’s history, advises, because the agency was shaped by director J. Edgar Hoover’s determination to discredit and disrupt the civil rights movement. The film taps several experts, authors of books on Withers, and archival footage of Withers’ FBI handler testifying at the 1978 House Select Committee on Assassinations, to provide insight about how someone might be recruited under pressure, how FBI reports relied on hearsay, and how agent careerism came to bear on the lives they were surveilling.

Withers’ extraordinary photographs offered a unique visual thread. Yasui reviewed nearly 15,000 of them and, with Bertelsen, selected 350 to be used in the film—sometimes as illustration, sometimes as counterpoint to the dialogue. For instance, one interviewee says that when a local Black activist attracted FBI scrutiny, Withers’ photo of the man allowed the FBI to add him to a shoot-to-kill watch list. That photo and the associated report are shown on screen together.

“These kinds of films, dense with historical information, pose a challenge,” says Yasui. “At 24 frames per second, it’s hard to absorb the details. So you have to make a film that makes sense to a one-time viewer, but also a film that stands up to freeze-frame scrutiny. What’s on the screen has to be accurate.”

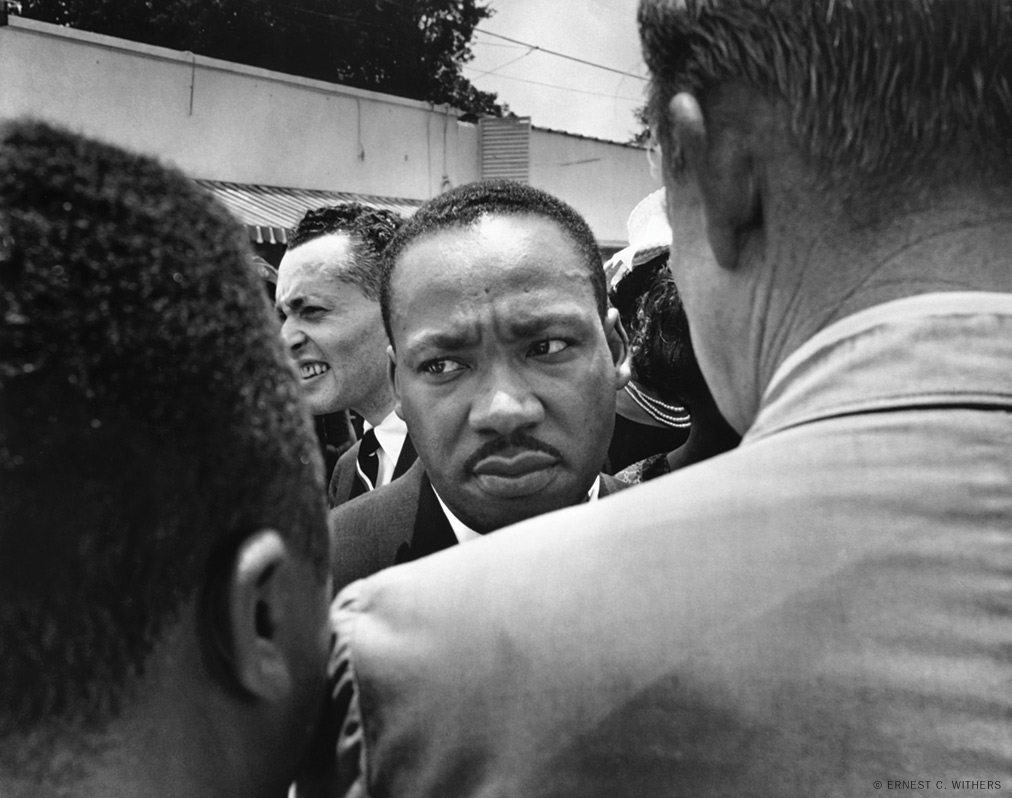

Withers’ photos serve to tell the story of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., at the Lorraine Motel, on April 4, 1968, providing the film’s emotional center. More than two dozen pictures create this sequence, starting with Withers’ coverage of the sanitation workers’ strike in February 1968 that brought King to Memphis a month later. Withers’ photos of the strikers carrying I AM A MAN signs became emblematic of that critical chapter. The subsequent March 25th demonstration and ensuing riot is told in a rapid succession of images: police swinging billy clubs, protesters running in every direction. Withers was at the center of the action.

King and his colleagues returned to Memphis on April 3 to attend a hearing on whether the city would permit another march to be held. Withers’ photos capture King at various moments during those two days before he was assassinated.

Harold Ford Sr., a member of Congress from Tennessee during that time, states in the film that he believes there were four or five informants the day of King’s murder who were reporting on his whereabouts. “We know from FBI reports that Ernest Withers was one of them.”

Although a lone shooter was eventually convicted of the assassination, controversy surrounding the investigation and the FBI’s role has been ongoing from the beginning.

“I’ve told the story of King’s assassination twice,” says Bertelsen. “The Picture Taker was the opportunity to really probe it from the standpoint of the FBI.”

“It’s an important part of our history that we need to understand,” says Yasui. “Many people are now calling for the FBI headquarters in Washington to be renamed, for Hoover’s name to be removed. There’s a story there.”

The Picture Taker tells the story of a man so dedicated to his community that he swings by at the end of his busy evening to photograph a little girl in her First Communion dress. And a man so deeply enmeshed in the contradictions and compromises of that era that he could say he was only at a tent city of sharecroppers kicked off their land for registering to vote “to take pictures and deliver them to the Negro newspapers.” Yet as this documentary ably illustrates, the story of Ernest Withers—and the history he helped document—is even more complex.

—Kathryn Smith Pyle