Looking back at the man who transformed conservativism.

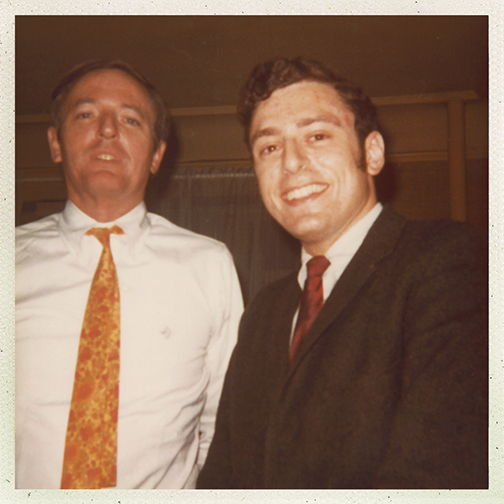

William F. Buckley Jr. first appeared on Alvin Felzenberg’s radar—and on the Felzenberg family’s TV—in 1965, when he was running for mayor of New York as the Conservative Party candidate. Felzenberg was then a sophomore at Irvington High School in New Jersey. And he was immediately hooked.

“I had never seen a more refreshing candidate for anything,” recalls Felzenberg, now a lecturer in the Annenberg School, in a lengthy phone interview. “The first question to him was, ‘What would you do if elected?’ He said, ‘I’d demand a recount.’”

Buckley also told reporters that he was running a “paradigmatic” campaign, which sent young Felzenberg scrambling for a dictionary. Soon he was reading Buckley’s widely syndicated (and polysyllabic) column to prepare for the SATs and devouring his increasingly influential magazine, National Review.

In Felzenberg’s new biography of Buckley, A Man and His Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. (Yale University Press, 2017), he focuses on the outsized role that Buckley played as a behind-the-scenes strategist in the political careers and presidencies that spanned his own career, which ended with his death in 2008.

“Someone once said that Arthur Schlesinger, God rest his soul, was a political consultant wearing a mortarboard,” says Felzenberg. “Buckley clearly was a political consultant masquerading as a journalist.” That career really started during his undergraduate days at Yale, where Buckley and his future brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell, “ran every organization worth joining on campus”—including, in Buckley’s case, the Yale Daily News—and knew where to find votes for whatever election was at hand.

After announcing in the inaugural issue of National Review in 1955 that the magazine would “stand athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so,” he evolved into a conservative kingmaker, one whom presidents and would-be presidents ignored at their peril.

Buckley’s influence on and personal connection with those presidents and candidates varied widely. His Buckley Rule of supporting the most “rightwardmost viable candidate” led him to endorse Barry Goldwater in 1964 and Richard Nixon in 1968 (though as the Watergate scandal unfolded he eventually called for the latter’s resignation). The president Buckley influenced most was Ronald Reagan, and Felzenberg devotes two chapters to the relationship of “Bill and Ronnie”—first “Preparing a President,” then “Advising a President.”

“Reagan said that Buckley did more to guide him on his journey from liberal Democrat to conservative Republican than anyone else, and did more to make the Reagan presidency possible than anyone else,” Felzenberg says. “And Reagan came to Buckley the old-fashioned way. He read National Review for six or seven years before they met. And he thought this guy was making sense.” The two became close friends—Felzenberg quotes Buckley’s son Christopher as saying he was “the only male friend that got through the veneer”—and he became close to the quietly influential Nancy Reagan as well.

“I thought that was fascinating,” Felzenberg says, “and that if I could get his letters and read about this triangular political operation between Ronald, Nancy, and Bill Buckley, I had a tremendous story.”

He certainly wasn’t lacking in material to work with, starting with Buckley’s 50-plus books, 5,600 newspaper columns, 35 years as editor-in-chief of National Review commentary, voluminous correspondence, and more than 1,100 television programs, including 33 years of Firing Line, the television program he started in 1966.

The last president who was able to ignore the upstart founder of National Review without paying a political price was Dwight Eisenhower, whom the young Buckley disdained for being insufficiently hardline against the Soviet Union. Yet Buckley defended Ike against the wild accusations of Robert Welch and his John Birch Society, who “believed that the Soviets were putting fluoride in our water to brainwash our children, and that the American government was run by Moscow—and that Dwight Eisenhower was a Communist,” notes Felzenberg. “That was absolutely appalling to Buckley and all the people at National Review.”

His decision, for reasons both principled and shrewd, to cast out what he called the “extremists, bigots, kooks, anti-Semites, and racists” is part of what made him both an effective leader and a compelling subject for a biographer.

“He considered his drumming out of the extremists his greatest lasting achievement,” says Felzenberg, acknowledging that the extremists have since returned. “He thought that any movement is defined by its weakest link in the chain—and that its opponents will certainly focus on its defects, so he’d better do it first. So he writes a series of editorials about Robert Welch.

“By 1965, when he’s running for mayor, he is now the spokesman for the conservative movement,” Felzenberg adds. Knowing that John Lindsay, the liberal Republican candidate, would take Lyndon Johnson’s approach to Goldwater and paint Buckley as a “tool of the Birchers,” he “decides to do a special issue of National Review, what I call ‘nuking the Birchers by the roots.’ And he gets every responsible conservative of 1965 to sign on with him.” It is, Felzenberg suggests, an example that the current Republican leadership should have followed.

“History will write that one of the greatest shames of the Republican Party of the last decade was the failure of its national leadership to attack the Birther movement in its cradle,” he says. “Our current president has been given credit for bringing it from the fringe and the underground conspiracy theorists right out into the open. And they’re really reaping the harvest of that.”

Buckley would have wanted a “much different response to Charlottesville,” Felzenberg adds, since he “believed, with every fiber in him, that we are the first country founded on an idea—not by conquest, not by bloodlines, not by tribalism, not by race. This is rather relevant to where we are going now.”

Buckley’s willingness to take on certain members of the conservative tribe extended to Ayn Rand, author of Atlas Shrugged, whom he (and Whittaker Chambers) attacked in National Review despite agreeing with her views on economic libertarianism.

“Buckley believed—it sounds somewhat corny to modern audiences—that man is created in God’s image and is given choices and is given gifts. And his greatest possible gift is to use his strengths and his abilities to glorify God in some way. And he went after Rand, because he didn’t believe that libertarianism was libertinism or a ticket to hedonism. It bore with it great responsibilities to use your talents to benefit others.”

The fact that Buckley once famously said that he’d “rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University” didn’t exactly indicate a conversion to populism.

“That’s an attack on liberal elites,” says Felzenberg. “What he really wanted was conservative elites. He never wanted a populist uprising because he was very fearful of the mob, of the crowd, of the tension, the violence.”

But he did lose some of his more virulent elitism, courtesy of a brief non-combat stint in the US Army, where he met a far less high-toned crowd than he had been raised with.

“This is culture shock,” says Felzenberg. “And it didn’t come easy to him.” For all his patrician elitism, Buckley had a surprising ability to connect with working-class voters—partly because of his wit and on-screen charm, which were comparable to John F. Kennedy’s, with whom he became disillusioned despite some lingering admiration. But it was more than that.

“Remember, he was a Catholic at a time when Catholics were discriminated against, whether he felt it personally or not,” says Felzenberg. “He was seen by working-class Catholics as all they wanted to be. He runs for mayor at a time when the courts are banning prayer in schools, ordering busing for racial balance. Those [working-class] parents are not able to send their kids to private schools. They’re saying, ‘We’re losing control. City Hall doesn’t care about us. And we’re the people who make the city go.’ Buckley stands up and says, ‘That is not racist. Listen to them.’ And so he becomes a hero. Everybody thought he would get the conservative Republican vote that was worried about budget and spending. No. He did better in Queens than he did at the Yale Club.”

Though Buckley retained some of conservatism’s more depressing prejudices—he once proposed that HIV-positive men be required to have their affliction tattooed on their bodies, and famously called arch-enemy Gore Vidal a “pink queer” on national television—he was willing to examine his views and change them. His biggest transformation was from patrician white supremacist to principled civil rights supporter. While Felzenberg acknowledges that “there’s no excuse for his atrocious, segregationist, racist editorials in the 1950s,” he puts it in context. “He grew up on both sides the son of a Southern family, and accepted their mores. They believed in white supremacy. But they also hated the Klan, and hated violence. He was coming of age when the Southern Bourbons, the genteel Southern noblesse oblige, were beginning to lose power in their own region to what Buckley called the ‘welfare populists.’ These were the violent types, who openly embraced the Klan.

“But after the Birmingham church bombing in 1963, which takes place a week after the March on Washington, he writes a letter to his mother in which he says that he’s tormented by this. ‘There’s nothing in the Catholic catechism that says whites are superior, that sanctions segregation, nothing that says black people are not made in the image of God. What am I supposed to do with this?’”

After openly opposing the 1964 Civil Rights Act on constitutional grounds, “by 1965 he did not oppose the Voting Rights Act,” says Felzenberg. “He basically says that the Southerners brought this on themselves with every resistance and violent act against demonstrators. So by the time the law takes effect, he’s completely repudiated the things that he wrote earlier. He [also] said, ‘I hear there’s a conspiracy to obliterate the KKK. Where do I sign up?’”

In 1969, at the recommendation of Daniel Patrick Moynihan (Richard Nixon’s domestic advisor), Buckley and several other journalists were invited by National Urban League President Whitney Young to tour several inner cities.

“He is charmed by self-help community organizers,” says Felzenberg. “He loves their sass, loves their wit, loves their contempt for bureaucracy. He believes that they’re lovers of children and want to make the community better. And he says, ‘One of them may well be president in 10 years.’ Well, we had a community-organizer president [40] years later, right? So his math may have been bad. But he saw that coming.”—SH