Thomas S. Kirkbride M1832 wrote the book—literally—on the housing and treatment of the mentally ill in the 19th century.

BY JOANN GRECO

Sidebar: Keeping “Kirkbrides” Alive

Walking along Philadelphia’s Race Street one summer day in 1840, Thomas Story Kirkbride M1832 happened to encounter a friend who was on the Board of Managers of Pennsylvania Hospital. His interlocutor relayed news of a position about to open at the prestigious institution. At first, the young physician assumed this must be the post of attending surgeon at the hospital, which (as he later wrote) he had coveted as “one of the most honorable and useful that could be held by any individual.” Kirkbride had been given to understand—by the incumbent surgeon, no less (John Rhea Barton, for whom Penn’s first endowed professorship in surgery was named)—that he “should be the successful candidate” upon Barton’s resignation from the post, which had recently been announced.

But to Kirkbride’s surprise, his friend had in mind another proposal entirely, asking instead “with apparent interest, what would induce me to go over the river, to take charge of the new Hospital for the Insane,” which Pennsylvania Hospital had recently established in West Philadelphia.

Although he wrote that his “professional friends regarded such a change in my plans as ill-advised,” since surgical openings were rare, Kirkbride was tempted by the fact that the asylum post offered the “opportunity of starting a new institution, and developing new forms of management, in fact giving a new character to the care of the insane, and possibly securing for myself a reputation as desirable as that which I might obtain by remaining in the city.”

Historian Nancy Tomes Gr’78, author of The Art of Asylum-Keeping: Thomas Story Kirkbride and the Origins of American Psychiatry , lays out the terms of his dilemma. “Surgery was growing into a prestigious specialty, and the decision wasn’t easy for him,” she explains. “He had always been frail, though, so ultimately he feared that he didn’t have the stamina for surgery.”

Kirkbride’s wife, the former Ann Jenks, wasn’t keen on the idea of a surgical career, either, fearful of the long hours away from home that the job would entail, while the care of the Hospital for the Insane would be sure to keep him somewhere on its premises. Kirkbride’s parents, too, were on board, favoring “my accepting this new office as being a certainty in place of an uncertainty.” And the position promised “a comfortable residence [and] a rather liberal salary.”

Kirkbride called the chance meeting “one of those incidents that seem beyond the control of men, and which changed the whole course of my life.” It certainly had a profound effect on the course of mental health treatment over much of the 19thcentury, as Kirkbride’s ideas shaped the construction and management of hospitals for the insane across the country, leaving behind as well a rich architectural legacy that, after decades of neglect, is at last being preserved and turned to fresh uses (see page 53). Kirkbride’s long tenure as the head of the Hospital for the Insane of the nation’s oldest medical institution, along with his influential writings, have assured him a permanent place among figures to be reckoned with by any student of the history of treating mental illness or early American medicine.

Tomes—now a SUNY Distinguished Professor of History at Stony Brook University—first encountered the groundbreaking physician in the course of her doctoral research in Penn’s history department. She views his legacy as three-fold: “Along with a few other contemporaries, he was instrumental in advancing the idea that the insane deserved care and not disdain or fear or curiosity,” she says. “Secondly, the treatise he developed on the design of mental institutions, which came out of these beliefs, influenced asylums for years to come; and finally, there’s the fact that he was one of the founders of what became known as the American Psychiatric Association,” the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII).

Tomes, who won the 2017 Bancroft Prize in American History and Diplomacy for Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers , has a personal fondness for the good doctor, too. “I owe him my tenure,” she says with a laugh. “As part of my research, I was taken to the West Philly hospital, and as I dug through boxes and boxes of archival material, it became clear that Kirkbride was the star. Those materials became my doctoral dissertation, which turned into the book, which started me on my path.”

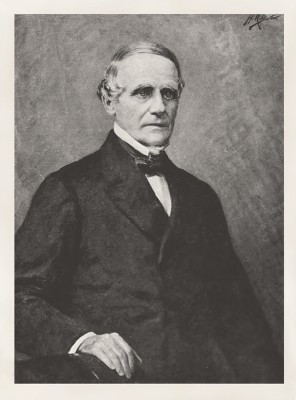

And a star he was. Kirkbride took up his post as superintendent of Pennsylvania Hospital’s asylum on January 1, 1841, and served until his death, shortly before midnight on December 16, 1883. In a commemorative volume issued by the AMSAII—which includes a “Memoir” mostly written in the third person relating Kirkbride’s life story but incorporating numerous direct quotes as well, including those above—it was noted that his 42-year tenure proceeded “without suggestion or thought, either on the part of the Managers of the Hospital or the public, that a more efficient or faithful administrator of the duties of this important place could be found.” The board also resolved, with no small flourish, that Kirkbride’s works and contributions to the subject of insanity “entitle him to rank very high among the benefactors of his race.”

Despite Kirkbride’s initial reported doubts, it wasn’t entirely out of left field that the hospital board would have thought of him to head its new asylum. While serving a two-year term as resident physician at Pennsylvania Hospital before opening his own medical practice on Arch Street, he had had “opportunities of studying the subject of mental disorders in the department of that Hospital which, for eighty years, had been specially set apart for that class of disorders,” as the “Memoir” puts it. Perhaps more significantly for his future treatment approach, immediately after graduating from Penn’s medical school, he had undertaken a year’s residency at the Friends Asylum in Philadelphia’s Frankford neighborhood.

That year would prove to be an illuminating one for Kirkbride, as it introduced him to the more humane treatment concepts then becoming popular in Europe, which he would adapt to his own practice. Dubbed the “moral treatment,” this approach had been developed independently in France—where the physician Philippe Pinel experimented with releasing the insane from their shackles and straitjackets—and in England by the Quaker William Tuke, who believed that if the insane were treated as friends and brethren, they would start acting like friends and brethren. “The patients’ minds were to be constantly stimulated by amusements such as games, lectures, and parties [and] regular physical exercise would tone their bodies and calm their minds,” writes Tomes. “If moral measures were carefully and diligently implemented,” she summarizes Tuke and Pinel’s conclusions, “no restraint or harsh treatment would be needed to control the insane.”

Kirkbride would never advocate the complete lack of restraint—indeed, he wrote in his 1877 report to the hospital board, “It is an error leading to wrong popular impression, to speak of any hospital for the insane as being conducted without restraint. There is no such thing, and cannot be,” noting that even control of the “gentlest kind” constitutes some form of restraint. But his whole approach was aimed at limiting such restraints through the design of the physical environment and by keeping patients usefully occupied. Sounding a note that runs through all his writings, he added, “The only persons who can properly decide just how far restrictions shall be carried, and freedom be granted in an institution, are its medical officers.”

Kirkbride came from an old Quaker family— Philadelphia’s Bridesburg neighborhood derives from a tract of land owned by an ancestor who made the crossing with William Penn. He grew up in rural Bucks County, Pennsylvania, the eldest of seven children, but knew early on that tending the family farm wasn’t for him. His father made no objection, and in fact was particularly keen on Thomas becoming a doctor, and so as a teenager, he was set early on a path that would lead to that career.

Kirkbride wrote of his education that his father was his first teacher, and he then attended local schools for several years: “2d, Morrisville; 3d, Fallsington, three miles distant, often walking in both directions.” For four years, he received a classical education at a Trenton, New Jersey, school run by “the Rev. Jared D. Fyler, a very accomplished scholar, and a teacher of rare ability,” and followed that up with a year in “the study of the higher mathematics, under the care of John Gunmere, at Burlington, New Jersey.”

He then spent the better part of a year on his father’s farm, “in the practical pursuits which I felt in later years to have been a permanent advantage to my health”—an appreciation of the benefits of outdoor activity that would inform his treatment ideas. He took a special interest in his father’s herd of sheep, he added, and “became so familiar with them as to recognize them by their physiognomy.”

At age 18, Kirkbride entered into a brief apprenticeship with Nicholas Belleville, an old-school physician—in Kirkbride’s accounting, he’d come to America originally with Lafayette’s forces at the time of the American Revolution, but was so seasick on the voyage that he never made the return trip to France—with connections to Philadelphia medical pioneers Thomas Bond, Benjamin Rush, and Phillip Syng Physick.

In 1828, Kirkbride gained admission to the University of Pennsylvania, where he “learned a much milder course of therapeutics than that advocated by his preceptor, Belleville,” writes Tomes. “He was instructed to avoid harsh drugs [and] to trust more in the body’s own healing powers.” In fact, in his thesis on neuralgia (nerve pain), Kirkbride offered a preview of the philosophy that would come to dominate his treatment regimen by recommending not only the standard medical treatments he had been taught but also encouraging that patients receive “active pursuits and cheerful society.”

Upon graduation, Kirkbride secured the Friends residency, but when that institution offered him a permanent position in 1833, he opted instead to leave for another residency at Pennsylvania Hospital. Located in the middle of what by now was a bustling city, the hospital had been established by Bond and Benjamin Franklin in 1751. Its charter included a promise to care for the sick, poor, and insane of the city, and its motto, “take care of him and I will repay thee,” was borrowed from the story of the Good Samaritan.

Despite these good intentions, treatment of the insane was harsh during the early days of the institution. According to a brief history posted on Penn Medicine’s website, these unfortunates were placed in “the dark, dank basement [and] chained to the wall and sometimes made to wear ‘madd-shirts,’ which restrained the movement of their arms. For the people of Philadelphia, it was considered a pastime to come to the hospital and peer into the rooms of the insane to witness their episodes … Keepers were given whips and … allowed to use them on patients.”

In part, these prisonlike conditions “merely reflected the violent character of its inhabitants,” writes Tomes, adding that “only the most dangerous and disruptive lunatics were placed in the hospital.” Under Benjamin Rush, later dubbed the “father of American psychiatry” and an attending physician there from 1783 until his death in 1813, things began to change.

While certainly not averse to the use of restraints, purging, and bloodletting, Rush was an early advocate for the view that mental illnesses stemmed from diseased minds rather than demonic meddling. Just as he had been instrumental in the early prison reforms that (after his death) led to the opening of the Quaker-inspired Eastern State Penitentiary, his wish that “mental illness be freed from moral stigma, and be treated with medicine rather than moralizing,” served as a guiding principle at the hospital.

This comparatively enlightened outlook prompted families to become more comfortable with the idea of relinquishing control of their loved ones, and the hospital’s population became more diverse in terms of the sex, class, and wealth of those committed. But the increased crowding that resulted led to the need for expansion, and the board of managers soon approved construction of a western addition, built for the sole purpose of housing the insane.

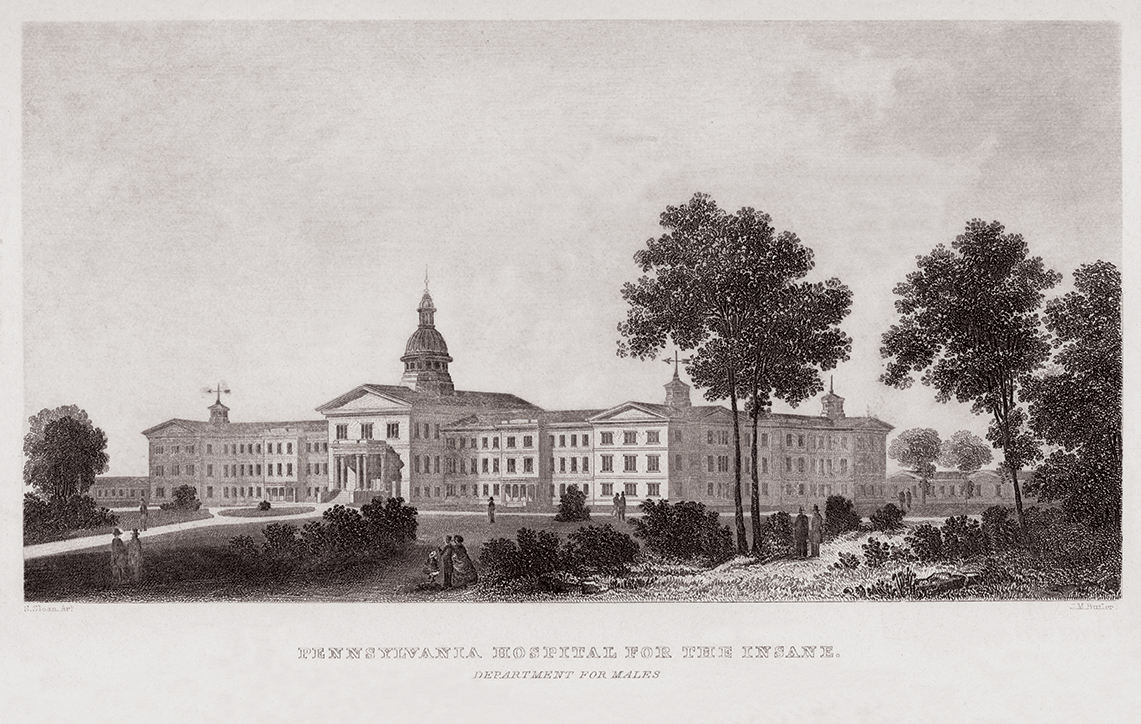

Opened in 1796, this section featured common “day” rooms where the more affluent patients—such as Mary Lum, who suffered from emotional outbursts and was committed by her husband, financier Stephen Girard—enjoyed the use of books, games, musical instruments, and writing implements. Eventually, this wing too exceeded its capacity—fueled, Tomes says, by a continuing move away from household care and a rapidly modernizing and urban society where behavioral niceties (and the inability to abide by them) were pushed to the fore. An entirely new building was necessary, and it was at this facility—the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, at 44th and Market Streets—that Kirkbride took the reins in January 1841. “[T]he first patient was received on January 9, 1841, and in a short time all the insane from the hospital in Pine Street were transferred to the new Institution,” the “Memoir” records. “He gave himself, mind and heart, to the duties of his position, and his zeal and enthusiasm for the welfare of the insane never slackened as long as life endured.”

Madhouse. Funny farm. Loony bin. Cuckoo ’ s nest. Snake pit. These disparaging terms and the disturbing images they conjure still run deep through our popular culture and psyches. At the time of Kirkbride’s reluctant entry into the care of the insane, the horrors of bedlam (a term which may derive from Europe’s oldest psychiatric institution, Bethlem Royal Hospital in London) were mostly confined behind the walls and hidden from the outside world.

Reform was in the air, though. In the same year that Kirkbride assumed his new position, the writer, schoolteacher, and activist Dorothea Dix—inspired by meeting Samuel Tuke (William’s grandson) and other mental health reformers during a trip to Europe—took it upon herself to embark on a statewide tour of Massachusetts in order to document the conditions in the prisons, private homes, and almshouses where the less privileged insane languished. She soon presented a report to the legislature. “I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, stalls, pens!” she wrote. “Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience.” Her passionate appeal led to an increased budget to expand the State Mental Hospital, and Dix took her campaign on the road, successfully persuading states like Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, Maryland, Louisiana, Alabama, South Carolina and North Carolina to assume greater responsibility for the mentally ill.

Back in West Philadelphia, Kirkbride took note of these developments, just as he remembered the lessons of moral treatment that he had experienced at the Friends asylum. Under Kirkbride’s direction, things were run very differently in the new facility than they had been in the Pine Street hospital. “First, he removed the restraints from the ‘dangerous’ patients and let them move freely in the wards,” writes Tomes. “The inmates sat down together to take their meals in a regular dining room, equipped with ordinary utensils and crockery, amenities unknown in the old institution. During the day, the doctors did not allow them to sit about unoccupied, but kept after them to read, play checkers or work around the grounds.” In his first annual report to hospital management, Kirkbride observed that “from this freedom of action, and from these indulgences, we have found nothing but advantage.”

In 1844, Kirkbride and a dozen other asylum superintendents met in Philadelphia to form the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, precursor to the American Psychiatric Association. Elected as the organization’s first secretary, he would serve in that capacity for seven years, then as vice president for seven years more, and president for another eight.

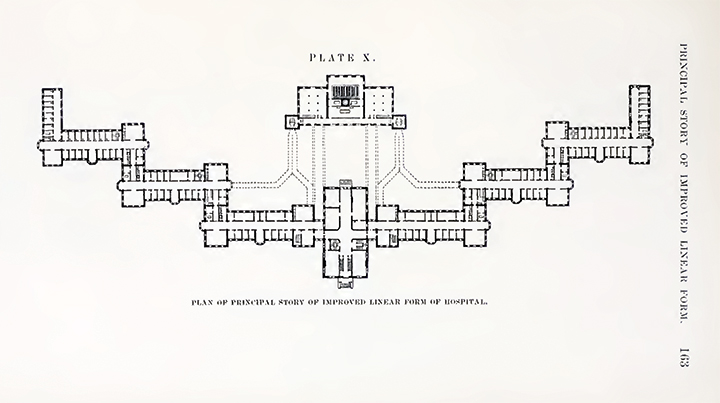

Meanwhile, he began to formulate his own thoughts about the ideal asylum, tying its architecture into its treatment regimen. He first spelled out his philosophy in an article in the American Journal of Medical Science in 1847. The next year, following the testimony of Dix before the New Jersey State Legislature, the first asylum built according to what would come to be called the “Kirkbride Plan” opened in Trenton.

In 1854, Kirkbride published On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangement of Hospitals for the Insane ; a second, expanded edition would appear in 1880, prepared during a long illness before Kirkbride’s death. As more states constructed new mental institutions, they turned to Kirkbride’s book as their bible and blueprint; eventually 75 facilities modeled after his ideas dotted the nation.

As the patient population at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane kept growing, the administration decided to build yet another facility on the grounds a few blocks away from the building at 44th and Market Streets. Here Kirkbride would finally get his chance to personally put into practice everything he had learned and written about. “He always felt that there were things he didn’t like about the Philadelphia asylum,” says Tomes. The new building, which was at 49th and Market and opened in 1859, was “Kirkbride’s baby from start to finish. Basically, it was his big, showy new piece of treatment.”

As reported in the “Memoir,” the new facility cost $355,907.57, including “the Hospital with all its out-buildings, the wall surrounding its grounds, all its varied and expensive fixtures of every kind and the furniture in use.” Kirkbride led the successful fundraising effort himself, and “labored with the greatest assiduity to collect by private subscription the money needed.”

For the project, Kirkbride hired a young architect, Samuel Sloan, who had served as a foreman during the construction of the earlier Philadelphia asylum. Sloan, who started his career as a carpenter working at Eastern State Penitentiary, wound up designing the greatest number of “Kirkbrides” of any architect and also provided the illustrations and plans included in Kirkbride’s treatise.

Kirkbride’s book specified everything from the site (at least two miles from a town of considerable size), acreage (at least 100 acres, much of it devoted to farms and gardens because Kirkbride believed that both the opportunity to work and to experience nature contributed to healing), and enclosure (a wall to provide privacy and security, about 10 feet high but placed far enough away from the building so as not to “give the idea of a prison”). He outlined details on plumbing, drainage, fire safety, lighting, and heating and ventilation. In essence, he tied design to functionality—as had Eastern State Penitentiary before it—in the conviction that the built environment can impact social behavior.

“He really understood the importance of suggesting confidence and calmness through the architecture,” says Robert Kirkbride GAr’90, dean of the School of Constructed Environments at Parsons School of Design, and an 11th-generation Kirkbride. “The Kirkbride Plan created a code that melded soft human touches to the physical environment to create a new way of treatment.”

Key to Kirkbride’s plan were two wings, stepped back in a V-shaped formation from either side of a central administration building. Each wing was separated by sex, and eight wards within each wing further divided the residents according to the severity of their illnesses (with the most impaired patients confined to the ground floor and farthest from the center, and the least closest to the center on the top floor). Each ward offered long, wide corridors featuring generous windows, high ceilings, and direct egress to the grounds outside. The central part of the building, through which visitors entered, contained administrative offices, back office functions such as the kitchen, and the superintendent’s apartment.

The meticulous Kirkbride also devoted considerable attention to managerial matters, delineating the roles of board members and outlining policies on admission, visitation, and the use of restraints. He also suggested the number of—and salaries for—assistant physicians, attendants, bakers, carpenters, carriage drivers, cooks, dairy maids, domestics, engineers, farmers, firemen, gardeners, ironers, jobbers, matrons, stewards, supervisors, teachers, washerwomen, and watchmen. For good measure, he offered a tally of staff—71 persons (36 males and 35 females) would live alongside the maximum of 250 patients that he recommended.

The critical takeaway when it came to organization, though, was Kirkbride’s insistence on the power of the superintendent. The superintendent, he wrote, “should have entire control of the medical, moral, and dietetic treatment of the patients, the unrestricted power of appointment and discharge of all persons engaged in their care, and should exercise a general supervision and direction of every department of the Institution.”

He also argued for a new nomenclature, such as substituting “hospital for the insane” for “asylum.” The latter term, he wrote, suggested that “those who entered were not sick, or did not come for treatment … rather they came as … though they had committed some crime or been banished from the sympathies as well as the presence of society.”

Life at a Kirkbride Plan facility was a far cry from the asylums of old, Tomes reports. Gone were the chains, bleeding and whipping, and while cupping and restraints were still used for the most manic cases, drug therapy (mostly morphine) was preferred. A schedule of work and leisure pursuits ruled the day, with patients participating in daily walks, putting in stints working the farms and gardens (though he warned against strenuous labor), and enjoying the library and billiards room. At his own hospital in West Philadelphia, Kirkbride even became famous for presenting magic lantern shows, offering residents the same pleasures and access to new technologies as their compatriots outside the walls were enjoying.

The mostly happy populace gave Kirkbride mostly rave reviews. Take Eliza Butler, an affluent young woman admitted in the winter of 1858 as suffering from a “melancholia of two months,” according to Tomes’ account. After she was discharged later that summer, Butler and Kirkbride stayed in touch and, years later, reader, she married him. (Kirkbride’s first wife, Ann, had died in 1862, likely of tuberculosis.)

Eliza would go on to become an advocate for school reform—South Philadelphia’s Eliza B. Kirkbride Elementary is named for her—and a crusader for the idea that through moral treatment the “insane” such as she could be cured. Writing to Dix, she noted that Kirkbride’s habit of “sitting down by patients and talking to them in the calm way, which I know from my personal experience, carries help and light to helpless, clouded minds.”

Eventually, modernity caught up with an aging Kirkbride. New laws emboldened patients to sue for being wrongly committed. Journalists balked at what they saw as over-promising by Kirkbride—only about half of all patients at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane eventually left as “cured,” a marked improvement over Rush’s time when just 17 percent of the insane were deemed “cured” but well short of the 80 percent that Kirkbride estimated could be cured using moral treatment. More generally, Kirkbride’s architectural dictates began to be viewed as too huge and expensive to implement and manage, while his insistence on the supremacy of the superintendent fell under increased statewide scrutiny. (Unlike Pennsylvania Hospital, most hospitals for the insane were public institutions.)

Without naming names, the writers of the “Memoir” pushed back against such second-guessing: “It has been the fashion with some who, with no practical experience, have pushed themselves forward in matters connected with building hospitals, to decry the plans as behind the age; but their plans have not yet been tried sufficiently long to prove their defects in all respects, and those defects will be found at the very points where they have departed from the well-considered details which he so carefully worked out.”

From the perspective of the present, architect Robert Kirkbride calls his ancestor’s eponymous plan “a cautionary tale to hubris and idealism.” In the end, though, the buildings and the theories, the magic lanterns and the pretty gardens weren’t really the point but rather means to an end. As Eliza Kirkbride observed in a memorial published shortly after her husband’s death, Kirkbride’s real strength was his “power over the afflicted.” That ministry, she continued, had been “more potent, perhaps, in itself than the many remedial agencies gathered within [his] Institution.”

JoAnn Greco writes frequently for the Gazette.

Sidebar

Keeping “Kirkbrides” Alive

In Upstate New York, Buffalo’s brand new Hotel Henry bills itself as an “urban resort.” Just minutes away from downtown, it’s set in an historic landscape (designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux and recently restored by Philadelphia’s Andropogon) of ancient white oaks complemented by native plantings, rain gardens, and sweeping lawns. Its castle-like building, the first professional commission for H. H. Richardson—an architect whose name graces a specific style, “Richardsonian Romanesque”—offers features like soaring 20-foot ceilings and curving corridors that act as sunlit interior “porches” for the 88 guest rooms.

A decade in the making and following a $102.5 million restoration, the resort is bringing new life to the former Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, which had been shuttered and deteriorating since the 1970s. It’s the latest and most visible turnaround of long-vacated “Kirkbrides”—mental hospitals built following the ideas of Thomas S. Kirkbride M1832—according to architect Robert Kirkbride, his descendant and founding trustee for PreservationWorks, a 501c3 organization advocating their preservation and adaptive reuse. Of the 75 Kirkbride Plan asylums that once stood, only 34 remain, he says, and 13 of those are still used as medical facilities of some sort. Another dozen have recently been, or are in the process of being, adaptively reused.

“Luckily, there’s a new generation of developers and users who appreciate the embodied labor in the buildings, as well as their historicity,” Kirkbride says. While the hospitals’ typical features and layouts—lots of small ‘cells,’ wide corridors, separate wings, and large common spaces—are not suitable for all uses, he adds, many surviving structures can work for mixed-use projects.

That’s been the case in Buffalo, where restaurants, an architecture center, meeting spaces, and other features are part of the Richardson-Olmsted complex that contains the Hotel Henry; and also in Traverse City, Michigan, where a developer reportedly bought an abandoned Kirkbride for $1 in 2002 and has over the years transformed it into a live-work-play complex.

Elsewhere, the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in Weston, West Virginia, now serves as an attraction offering historic and ghost tours, while the Oregon State Museum of Mental Health in Salem takes a more serious approach to the issues surrounding treatment of the insane. The latter, which is in a building on one of the few Kirkbride campuses located west of the Mississippi, was the setting for the 1975 movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Parts of the complex are still used as a psychiatric hospital.

Several other adaptive reuses of Kirkbrides are currently under development. In the nation’s capital, St. Elizabeths Hospital—an asylum that once housed President James Garfield’s assassin, Charles H. Guiteau, and Ronald Reagan’s would-be killer John Hinckley Jr.—is being converted, with no apparent irony, into the new headquarters for the Department of Homeland Security. Plans are underway to transform the Hudson River State Hospital in Poughkeepsie, New York, into the $250 million Hudson Heritage development, with homes, shopping, and a boutique hotel included in the project. And in Tuscaloosa, the Alabama Hospital for the Insane will become a welcome center and provide new museum galleries for the University of Alabama.

“These buildings are beautifully constructed—we’ll never be able to build again with these materials and attention to craftsmanship,” Kirkbride says. But more than that, he adds, they are “remarkable physical documents from a certain time in history.”—JG