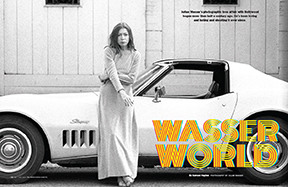

Julian Wasser’s photographic love affair with Hollywood began more than half a century ago. He’s been loving and hating and shooting it ever since.

BY SAMUEL HUGHES | Photography by Julian Wasser

At one point during our long, careening, R-rated conversation over lunch at La Scala Presto, I tell Julian Wasser C’55 that I wish I could go back with him to some of those early shoots in the Los Angeles of his salad days. He assesses my sanity through probing eyes. Then: “Do it!”

Click.

“It was a golden age and a hopeful time,” he writes in the introduction to The Way We Were: The Photography of Julian Wasser, a coffee-table book of his work published two years ago by Damiani. “Angelenos weren’t just existing, they were living. For a photographer, too, life was good.”

That it was, especially for a young man who had fled the gritty urban East of his youth and hitched a ride around the world with the US Navy, doing photo intelligence and reconnaissance. When his inner compass steered him to the City of Angels, it turned out to be more than just a place to live. It was a character, I suggest—a dazzling, seductive, outsized character in his work.

“It always was,” he agrees. “I was in the Navy, in San Diego. I came up here, and it was like Sodom and Gomorrah—a dream! I saw how everybody—guys and girls—they were all beautiful. I said, ‘Can I live here? How am I even gonna get a date?’”

But you did all right, I say.

“Yeah, well—the Sixties came along, and that became my decade.”

Click.

Until a few months ago, Wasser wasn’t even a blip on my radar. Then in January we got a call from David Pullman C’83 [“Alumni Profiles,” April 1997]. He had just met an older alumnus in LA who had photographed Marcel Duchamp and David Bowie and dozens of the brightest stars in the Hollywood firmament—and the Gazette really needed to check out his work. Pullman’s enthusiasm spilled out in torrents, and after I hung up I went to julianwasser.com and started poking around. Within a few seconds my eyes were popping. There they were:

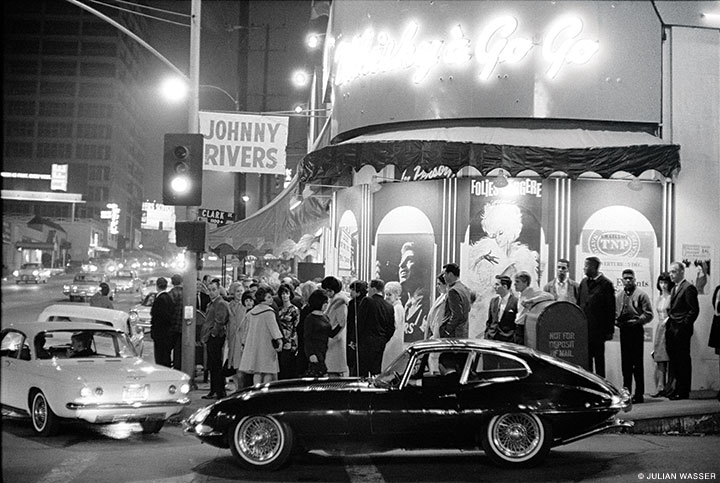

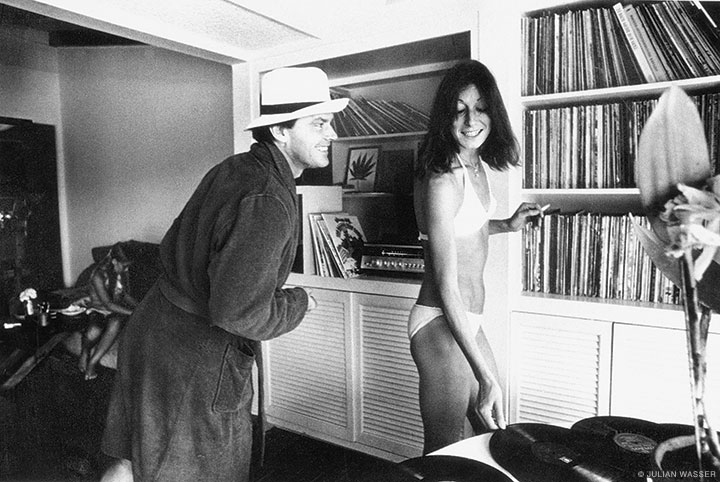

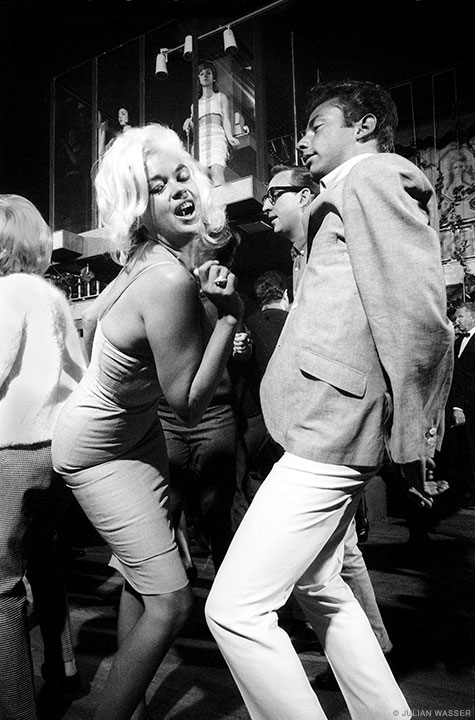

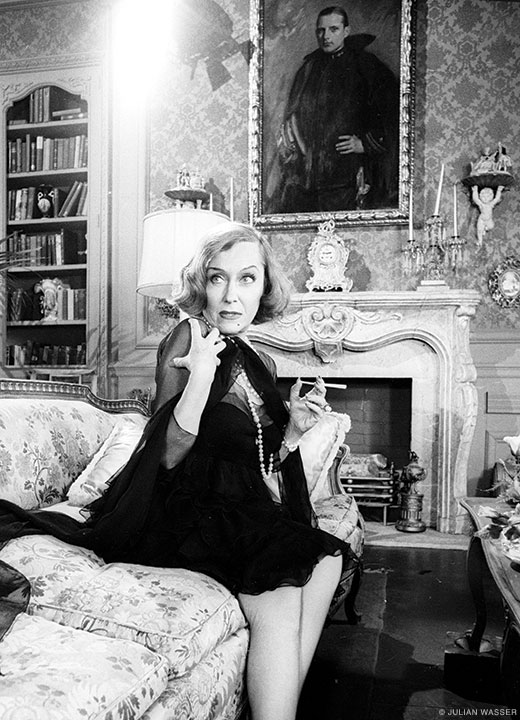

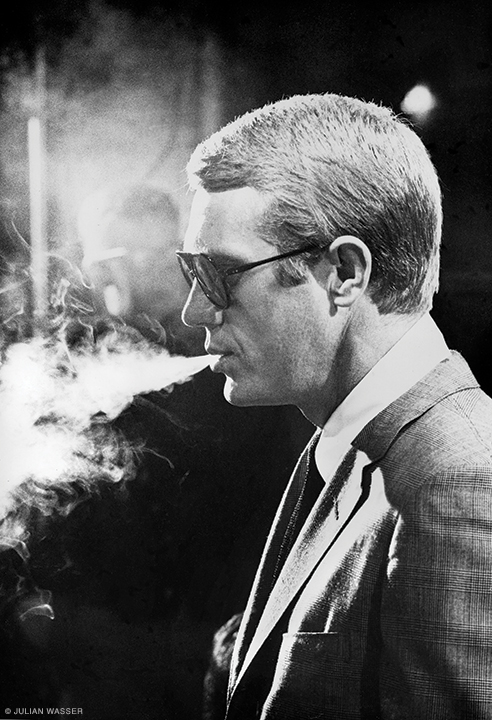

Steve McQueen, a portrait of smoke and ice on the set of Love with the Proper Stranger. Jack Nicholson, horsing around in his Mulholland Drive digs with Anjelica Huston (he’s grinning like a deranged Ed Norton in a bathrobe and backwards Panama hat; she’s smiling coyly in her tiny bikini, a cigarette in her left hand, an LP in her right). Jayne Mansfield, whose eye-melting form lit up the cover of Hollywood Babylon, getting down and dirty on the dance floor at the Whisky à Go Go. Bobby Kennedy, surrounded by jubilant supporters and reporters at the Ambassador Hotel after the 1968 California primary—just five minutes before he was murdered in the hotel’s kitchen. Iggy Pop, bare-chested on stage at Rodney’s English Disco, being bull-whipped with disturbing intensity by a guitarist dressed in Nazi regalia. Not to mention Gloria Swanson and Jodie Foster and John Travolta and the Brian Jones-era Stones and—well, so many more that I won’t even try to sketch a representative sample, lest my prose bring on what I’ll call the Didion Principle.

In 1968, Wasser photographed Joan Didion for a Time magazine article celebrating her just-published collection of LA-centric essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. In one photo she stands in a long-sleeve maxi dress in front of her Stingray Corvette; in another, she holds her two-year-old daughter, Quintana Roo, in her lap. In both, she gazes intently at the camera, holding a cigarette. Forty-six years later, she would tell an interviewer from Vogue: “Anybody who had their picture taken by Julian felt blessed.” Asked how she felt about that Time article, she replied: “I don’t remember the article. I remember the pictures.”

Click.

We meet, at Wasser’s suggestion, at La Scala Presto, the Brentwood offshoot of Jean Leon’s original Beverly Hills star palace. It doesn’t really feel like an It Spot, despite all the framed caricatures of stars on the walls, but the food is good and it works for a lunch interview. Though I’ve never met him or seen his picture, I know it’s Wasser as soon as I see him hurrying toward the door. He has astonished eyes, the urgency of a deadline reporter, and the physique of a hunger-striker, thanks to open-heart surgery just a month before.

It doesn’t take long to figure out that this is going to be a live one. Within seconds of our meeting, Wasser explodes at a waiter for nixing the booth we wanted after telling us we could sit anywhere. (He asks me not to repeat what he said, so I’ll just say it was colorful.)

“I’m surprised I survived this operation,” he says in a raspy voice after we settle into another booth. “I went to France—I felt really shitty. I’d walk 50 steps and it hurt so much that I had to stop for two minutes, leaning against the wall. So I came back to LA, went to a doctor. He said, ‘Your coronary arteries are 99 percent blocked. You have to have an operation immediately or you’re gonna die.’ So I did it. Oh, it’s horrible. I feel so bad now, so weak, it’s awful.”

Yet there’s something almost boyish about his appearance. He won’t divulge his age (“I’m like an actress that way”), though you can ballpark it with the help of the C’55 algorithm. His face has a touch of film star, albeit a protean one. At times he reminds me of Christopher Walken, and when he flashes his disarming smile I glimpse Henry Fonda (whom he once photographed in the actor’s home, flanked by Peter and Jane). All things considered, I tell him, he looks pretty good.

“Yeah, right,” he says. “I sit in the sun; I eat all the good stuff. I’m eating almond butter with a spoon—everything with calories. I lost 25 pounds—it’s horrible!”

The next day he shoots me an email that gives some context to his pique with the waiter (whom he later buttered up, more or less successfully). The gist of it is that after Jean Leon died, the maître d’ and staff who had once made the place feel like a “private Beverly Hills club” left, and those who replaced them were mostly “indifferent.” The bottom line is a refrain that he keeps coming back to: “the Hollywood magic was gone.”

Click.

“Whether shooting the beautiful people or social documentary, my intent as a photographer never changed,” he writes in The Way We Were: “to be where things were happening, to meet the people who were responsible for the world we live in, and, through my pictures, to evoke in viewers what I saw and felt at the instant I tripped the shutter.”

At our lunch, he offers a pithier goal: “I wanted to show life as it was.” I’m in the Emerson camp when it comes to foolish consistencies, so I’ll just say that he clearly meant “life as it was in certain parts of LA,” and that even then he should be given some artistic license. When I ask him about another famous Penn photographer, the late Mary Ellen Mark FA’62 ASC’64 Hon’94, for example, he responds: “I don’t care about dingy Bombay neighborhoods, working-class brothels. I want pretty things. I think photography should add to the beauty of the world.”

And yet, I point out, he’s photographed some not-very-pretty things himself.

“Well, I show what is!” he says. “If I see a cop beating all these black kids, I’m gonna show it. It’s part of life. But it’s not the only part of my life. It’s not an image I’m gonna say, ‘This is an example of my work.’”

For a photojournalist, he adds, the bottom line is: “It’s not how good you are. It’s that you’re reliable, and you always come up with a set of usable photos. And I always did that.”

Click.

Wasser’s standard for usable is a good deal higher than most, and by the time he got to LA, he had already learned his craft in some very challenging situations (more on that later). In this casually hot new world, the planets were aligned with the stars in a syzygy that is unlikely to be seen again.

“I was working for Time and Life, the hottest magazines on planet Earth,” he says. “So whenever they wanted a picture of anybody, they could get it. It’s not like now, with the paparazzi and the scandal TV shows. You saw everybody all the time, you could talk to them. Now there’s layer upon layer of protection based on economic factors. So now you have these mole-like pieces of shit who, because they’re so wealthy, you can’t get near ’em! It’s horrible!”

In some cases, his familiarity with the scene and maybe his own mercurial charm must have helped him get access. Yet wouldn’t a photographer have had to work hard to build trust with the likes of Jack Nicholson?

“No!” Wasser says incredulously. “He didn’t give a shit. You come in and you photograph him, he’ll make another $100,000 from that story. What the hell did he have to trust me for?”

But if the stars were closer to Earth then, that doesn’t mean they always wanted to see you shooting them, on set or anywhere else.

“The two guys who made my life the toughest were Charles Bronson and David Carradine,” he says. “Bronson. Just. Would. Not. Cooperate. Whenever I brought my camera he’d turn his head away. I had to be real fast to get him.” Carradine told him flat-out that he was going to make his life miserable.

Then there was Raquel Welch, who had him kicked off the set of Bob Hope’s Christmas Special one year.

“I was in her line of sight,” he explains. “She could look and see me. She said, ‘Get him outta here!’ And Bob Hope goes, ‘I’m really sorry, but it’s either you or her.’”

A similar thing happened with Doris Day. “I was shooting some kind of shit she was doing at Twentieth [Century Fox], and I went to take a piss. I was standing by the urinal, and the publicist comes scuttling up to me and says, ‘You’ve gotta leave this set immediately. Miss Day doesn’t want you here anymore.’” He shakes his head. “That’s when you want to puke.”

“Some people are control freaks,” he adds. “So what can you do? Live and learn. I go on a set now, I wear dark clothes and I keep out of everybody’s line of eyesight. But it’s worse now.”

Click.

It wasn’t the music per se that drew Wasser to the Beach Boys and the Jackson 5 and Joan Jett and Jagger.

“I shot all the bands,” he says with a shrug. “That was big money then.” More to the point: “It was a phenomenon.”

One night in what he thinks was 1972, Wasser was at a party at some lawyer’s house above the Sunset Strip when he saw Rodney Bingenheimer, the publicist and KROQ DJ, standing with an attractive, epicene young man with long, flowing hair and a long, flowing floral dress. It was David Bowie. Wasser’s reaction as he pressed the shutter? “No reaction! I was photographing Rodney, not Bowie. Bowie was nobody then—can you believe it? Rodney was the guy who introduced him to RCA and to America.”

Several years later, at The Forum, Wasser snapped what proved to be an iconic image of Bowie, the essence of chiseled androgyny—a quality heightened by the ghostly, Chorus Line-like apparition of five more Bowies beside him. Wasser had just bought a $30 splitter filter from Spiratone, the cut-rate photo company, and he liked the effect.

“In photography, you’ve gotta try everything,” he says. “It’s like the Beatles’ music backwards—whatever works.”

Somewhere around 1964, another California phenomenon, not unrelated to the music, “blew a mist over the entire scene,” as he puts it in The Way We Were.

“The whole hippie thing,” he says. “That was a real movement, an earth-shaking thing. LSD, all that stuff. I knew I was part of something very, very big. Most of those people didn’t come out of it very well. They got big psychological troubles, physical troubles. A lot of them died young. I was glad not to be part of that. I was never into drugs. Never, never, never.”

Click.

August, 1969. Film director Roman Polanski kneels on the stone patio of his Cielo Drive home in Benedict Canyon. On a wooden chair beside him sits a large Polaroid camera. He turns to look at the white door, which has the word Pig written on it in blood that has dried to a rusty orange. Until a few nights before, that blood had been flowing through the veins of his pregnant wife, the actress Sharon Tate. That was when members of the Manson Family cut the telephone lines, broke into the house, and stabbed her—and four others—to death.

At that time, the LA police had no clue who was behind the murders, and the desperate, grieving Polanski hoped that a psychic might be able to pick up some vibes from Polaroid photos taken at the scene.

“Tommy Johnson, the entertainment editor of Life, was a friend of Roman’s,” recalls Wasser. “He called me. We went up with two cops, the psychic Peter Hurkos, his assistant, and a couple of other people, so I could take Polaroids and Hurkos could look at my photos and find out who the murderer was.” Inside the house, Wasser took another picture: of a nightstand with a framed photograph of Polanski and Tate on their wedding day. Beside it is a white telephone, smeared with blood.

Polanski was “destroyed” by the murder, says Wasser. “We were in his nursery, and he was looking at all these 11 x 14 photos in the drawer, and he started crying. I felt like I was a grave robber, even though he had invited me.

“I used to see him in Paris a lot” in the years that followed, he adds quietly. “I never wanted to remind him of how we had met.”

Click.

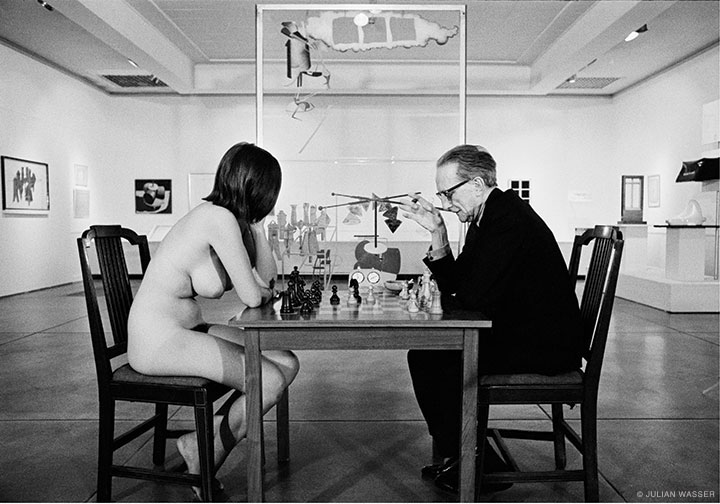

Time never used the photos Wasser took of Marcel Duchamp in October 1963, when the Pasadena Art Museum held the first-ever retrospective of the legendary artist’s work. But they were some of the most memorable images he ever made.

“When I went out to photograph him for Time, I didn’t even know who he was,” Wasser says. “I knew he had done that Nude Descending a Staircase, so I saw him as this old guy, and I respected him because of that 1912 portrait.”

In one photo, Duchamp sits pensively before his Bicycle Wheel, holding a short cigar; in another, he puffs on the cigar in front of his famous porcelain Fountain. Both are terrific images, but neither grabs the eyeballs so brazenly as the one in which the gaunt, elderly artist sits at a table in the museum, playing chess with a naked, voluptuous young woman named Eve Babitz. Behind them is Duchamp’s Dada work, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelor, Even.

Wasser not only took the photo but had set it up. He and Babitz—among others—recently recounted their roles in that tableau vivant for a Vanity Fair article that chronicled its many backstories, sexual and otherwise. (At one point Babitz recalled watching Duchamp play chess with museum director Walter Hopps, with whom she was having an affair: “And then Julian came up to me. ‘Hey Eve,’ he said, ‘how about I take a picture of you and Duchamp? You’ll be naked.’ And I thought about it. And I thought it was maybe the best idea ever.”)

“I asked Eve because she had a very classic female body, OK?” Wasser told that magazine. “I asked her because I knew she’d blow Duchamp’s mind. And you know what? She did. She blew his mind!”

Click.

My guess is that Wasser was always a wise guy—that he came into the world quick, feisty, tenacious. True, he spent his childhood in the Bronx (Grand Concourse) and his formative years chasing crime in Washington, both of which had some effect on him. But whichever theory of human personality you subscribe to, he was sufficiently in touch with his inner gadfly that by the time he was 14, his DC public school had had quite enough of him.

“I was so bad,” he says. “A troublemaker, making noises, disrupting classes—the teachers all hated me. I was in the principal’s office all the time. My mother was a substitute teacher—it was so embarrassing. I guess I was subconsciously looking to get out of there. So they moved me to Friends.”

That would be Sidwell Friends, the Quaker school whose student body currently includes Sasha and Malia Obama. (One of their father’s two favorite photos—Wasser’s 1963 photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. speaking in LA—hangs in the White House.) Wasser is not what you’d call the quintessential Quaker, but Sidwell seems to have been a pretty good fit.

“Private schools are great,” he says. “The headmaster called me in one time and said, ‘You’re a real wise guy—we don’t like the way you are. If you don’t change your behavior, you’re not coming back here next year.’ And I got so good, immediately. I shaped up real quick.”

His real education was decidedly extra-curricular. By the time he switched schools he was already working as a copy boy for the Associated Press’s DC bureau. His goal was to be a spot-news photographer, and he took to the violent crimes in that segregated city like a shark to chum-filled waters, guided by a police radio that he had installed in his father’s car. Soon he was selling his pictures to The Washington Post. The fact that he was “way underage” and lacked a driver’s license didn’t stop him from sneaking out.

“I would just listen for police calls, and go respond to fires and accidents and shoot them,” he says. “My father would see one of my photos on the front page of the Post the next day and say, ‘Oh—there’s another Julian Wasser that’s a photographer.’”

His father had already helped jump-start his career by giving him a Contax 35mm that a friend had taken during the war from a dead or captured German officer. It wasn’t exactly what young Julian had in mind, though he used it.

“I thought 35 was just for assholes,” he says. “I wanted the Speed Graphic—that’s what I saved my money for.”

Speed Graphic was the camera of choice for a legendary New York crime photographer named Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee. When he visited DC to promote a company’s brand of film, he stopped by the AP bureau and let the awestruck copy boy ride around with him in his car.

“That was a real big deal,” says Wasser. “He was the dean of spot-news photographers. And a dirty, disgusting person. Anything you could imagine about him, that’s what he was. And he was my hero!”

Wasser’s AP apprenticeship was serious business. “I worked from 3:30 until midnight,” he recalls, “and then if the guy didn’t come in at midnight I worked until 8 in the morning, all the way through.” Any “mentorship” by those hardboiled photographers seems to have come in the form of abuse.

“They would have a pornographic picture floating in the fixer, and they’d say, ‘Hey kid, can you bring it to us?’ I reached in—it had a capacitor in it—and I got a tremendous shock! I’d come running out all white-faced, and they’d be laughing their asses off.”

The photographers also had a TV in the office. “They’d say, ‘Kid, turn the TV on.’ I turned it on and it had another capacitor—so it exploded! They said, ‘You blew up our TV, you little fuck! You owe us $400!’” He laughs, a bit darkly. “The good old days.”

“You were a kid—a piece of shit—and they were gonna make you suffer,” he says by way of explanation. “These were all the White House photographers, all these real tough, hardened, AP guys—I was what they laughed at. You didn’t get angry or let your feelings get hurt—because you’re nobody, right? Now, their feelings get hurt and they go murder their parents. They have self-esteem. We didn’t have that then.”

His editor at the Post wasn’t any better than the AP guys.

“He was so crude and ruthless with me,” Wasser recalls. “I wrote him a letter years later, and I said, ‘Thank you—for putting me in the magazine business.’ At least they didn’t mistreat their people.”

Yet all that brutal hazing clearly toughened his skin, which had to have been helpful in the long run, right?

“For a photographer?” he asks incredulously. “Oh yeah—shit, ’cause you never take No for an answer, no matter what. There was plenty of ‘No, no, get out, fuck off, get lost’ [in Hollywood]. So you don’t quit. You don’t give up.”

Click.

By the time he transferred to Penn in the fall of 1952 , after a dispiriting year at Colgate, Wasser had pretty much lost interest in crime photography. “Who doesn’t?” he says. “It’s low-life!”

He now wanted to be a magazine photographer and “make images that, while still documenting daily life, would be more iconic and lasting than most crime photos,” he notes in The Way We Were. By then he had upgraded to Nikon.

He took mostly journalism classes from English professor Reese James, though once again, his real education was hands-on: as head photo editor for The Daily Pennsylvanian and as a freelancer for the Gazette. After he rented a small plane and took more than 100 aerial photos of Penn’s campus, the Gazette ran a three-page photo spread in its March 1955 issue titled “The University from the Air.” It included this editorial note: “Julian has been snapping shutters at just about everything he has seen for a number of years now, and he plans to make photography his profession after graduation in June.”

Though Penn’s tuition in those days was only $700 a year—paid for by his grandmother as a reward for submitting to the “torture” of his bar mitzvah—Wasser needed money. He made it covering the fraternity scene.

“I would photograph all these Gentile fraternity parties and sell prints,” he says. “It was segregated, Gentile and Jewish—the Rush Guide of that era had you and your picture, and next to your name was H for Hebrew, C for Catholic, P for Protestant. How do you get away with that shit? It should be illegal! So I took these pictures, all the guys with their Fifties dates with their bouffant hairdos and their expensive gowns.”

For his senior thesis he interviewed the likes of Richard Avedon, Alexey Brodovitch, and Allan and Diane Arbus. He liked Allan’s work more than Diane’s, especially after he saw some of her portraits in the Museum of Modern Art of people that he knew personally.

“She made them look like monsters!” he says disgustedly. “She was projecting her own tortured soul. So fuck that! I don’t want to see that. If she’s got problems, let her go to her therapist and work it out.”

Click.

Back at La Scala Presto , I’m wondering if there was a specific moment when Wasser concluded that the old LA magic had disappeared. Or did it? Is the city and its exotic, cocooned community of stars and beauty-worshippers still reinventing itself?

“It’s still magic,” he says, despite having spent a good part of the last two hours complaining about it. It seems he has come to appreciate the place a little more after living in Paris for a couple of years.

“Paris is shit compared to LA,” he says. “Well, it’s beautiful, it’s lovely, the ambience is this deep—but it’s horrible! Everybody lives like a dog there. They’re all uptight; it’s this hierarchical society; everything is difficult to do—impossible. They’re always arguing and bending your ear with all this stupid shit. All the women there make trouble. I mean, they’ve got great croissants, but it’s better here. It’s transparent here. What you see is what you get here.”

I ask him what drives him to keep shooting. He rubs his thumb and first two fingers together: “Money. What else?” But a few seconds later his film noir persona softens to take on another dimension.

“You gotta keep working, too,” he says. “If you don’t keep shooting you lose the edge. I would shoot on my own just for the hell of it, just to keep sharp. You can’t stop.”

At the end of our conversation, I ask if I can take his picture with my iPhone, just for personal reference. He agrees, but looks a little worried. “I got a good photo I’ll give you,” he says. “Really.”

Relax, I say. We won’t run anything I take in the Gazette.

So he smiles, an uncharacteristically bright and cheerful smile for the camera—and holds it for maybe three seconds.

“Click—shoot!” he snaps.

Click.

“That’s it. Enough.”

Thank you for your article on U Penn alumni Julian Wasser. I learned more about my father from your paper then I ever did from my family!

Relay my thanks to the author S Hughes.

Best regards,

James Wasser