Carl Cheng’s ruminations on the Anthropocene epoch take over the ICA.

Carl Cheng’s first in-depth museum survey, at Penn’s Institute of Contemporary Art through April 6, may be overdue. As a commentary on the precarity of human claims on the environment, Carl Cheng: Nature Never Loses is also eerily timely.

With fires still ravaging Southern California when the show opened in January, the 83-year-old, Santa Monica–based artist seemed to be directly addressing his community’s most pressing concerns. But, in fact, those same concerns have animated him for more than six decades.

“I don’t feel like I’m predicting the future for anybody,” Cheng says. “It’s just that I’m living our present. I am documenting what we are doing.”

Born in San Francisco, one of five sons in a Chinese American immigrant family, Cheng has long wrestled with the complicated interactions between human beings and nature. He was “creating work about global climate change before the term ‘global warming’ was even born,” says Hallie Ringle, interim director and Daniel and Brett Sundheim Chief Curator at the ICA. “And his practice feels so much more resonant today, especially as we collectively grapple with the increasing impact of global warming.”

While Cheng has experimented with a variety of media, many of his themes have remained constant: the perils and promise of technology, the notion of identity, the role of art institutions as gatekeepers. Schooled in art and industrial design (at UCLA) and the Bauhaus tradition (at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen, Germany), he has hand-crafted “art tools” and “nature machines” whose functions include creating sand sculptures and replicating the process of erosion.

In recent years Cheng has turned to public art commissions to secure funding and reach larger audiences. Not incidentally, those public installations, whether intended as permanent or evanescent, often thrust his art into direct conversation with natural environments.

In Santa Monica Art Tool (Walk on L.A.) (1983–88), a massive, tractor-driven concrete cylinder stamped a design corresponding to the topography of Los Angeles onto the Santa Monica beach. The intricate relief, a sort of elaborate sandcastle, included recognizable city landmarks and even the requisite traffic jam.

Santa Monica beachgoers were not meant to be passive viewers. In ironic defiance of the shibboleth that nobody walks in Los Angeles, they were invited to participate in the artwork by treading on it, mimicking the depredations of Godzilla. A video in Nature Never Loses captures the project’s cycle of creation and destruction.

The thematically organized Cheng exhibition represents the culmination of a five-year labor of love for its curator, Alex Klein, former senior curator at the ICA and now head curator and director of curatorial affairs at the Contemporary Austin, where the exhibition debuted. Denise Ryner, the ICA’s Andrea B. Laporte Curator, organized the display in Philadelphia.

The show will travel to two European venues—Bonnefanten in Maastricht, Netherlands, and Museum Tinguely, in Basel, Switzerland—before ending its tour at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Apart from six loans, all of the roughly 60 items come from the artist’s studio, Klein says.

“It’s been a heavy week installing this show, which is so much about Los Angeles and comes so much out of Carl’s experience growing up there and living there,” she says.

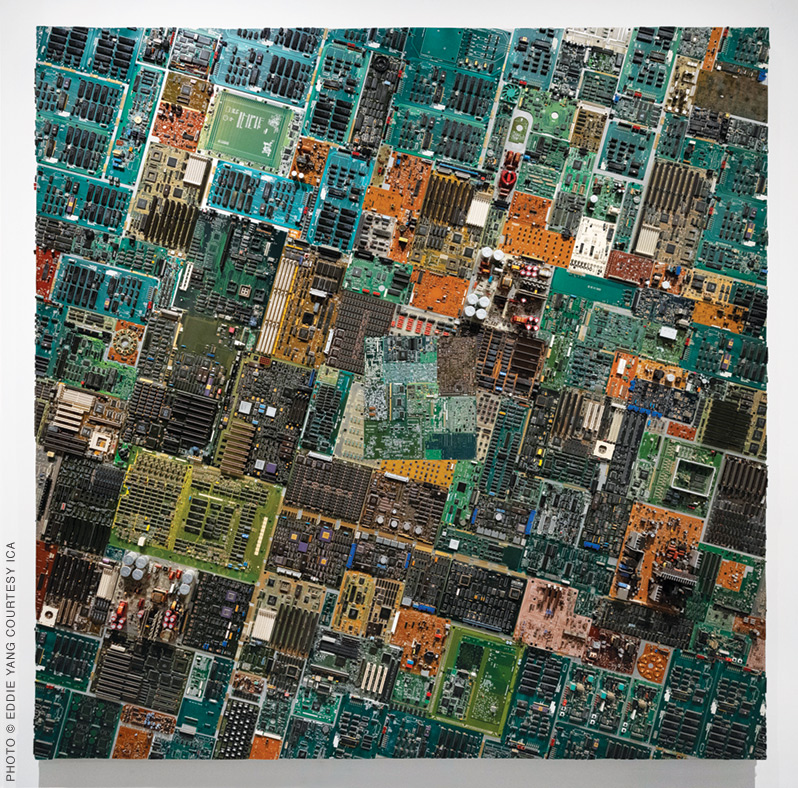

Divided into six sections, Nature Never Loses begins with Anthropocene Landscape 1 and Anthropocene Landscape 2, both from 2006, two particularly beautiful works that sum up Cheng’s preoccupations. Each is constructed of computer parts—printed circuit boards and rivets on aluminum. The second piecereflects the industry’s increasing miniaturization. With their geometric designs and colors, the works evoke aerial landscapes as seen from different elevations—an unintentional reminder of recent views of the devastation of Pacific Palisades, Altadena, and other Southern California neighborhoods. (The term “Anthropocene” refers to a geological epoch in which humans have begun to impact climate and the environment.)

Much of Cheng’s early work interrogated the conventions of photography. He used plastic, wood and plexiglass to construct photographic sculptures, and photocollage to juxtapose different images of a Pacific Coast landscape. In his Scroll Series, he cut rectangular holes in scrolls and had participants use them to frame views of the Great Wall of China and other iconic vistas, underlining the subjectivity and artifice of photography.

Klein first encountered Cheng through his photographic sculptures. When she saw his weirdly idiosyncratic Erosion Machines, “my mind was blown,” she says. For these contraptions, one for each of the five Cheng brothers, the artist fabricated “human rocks” out of organic and inorganic materials and subjected some to streams of water to produce erosion.

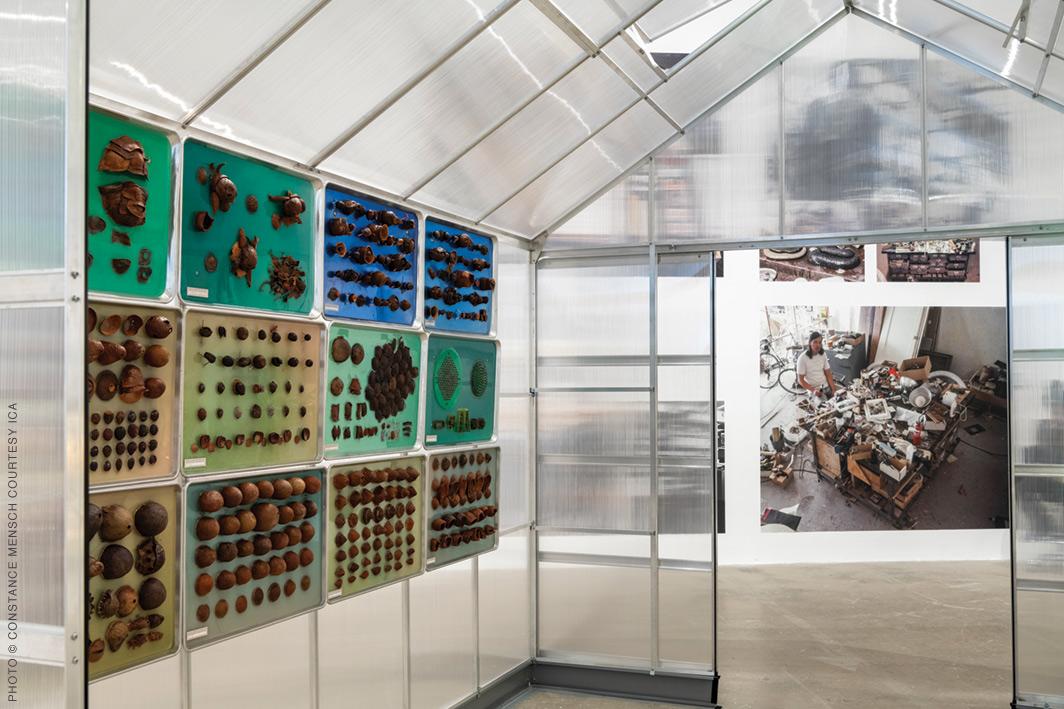

One gallery is anchored by Cheng’s Avocado Laboratory (1998–2024), a greenhouse filled with whimsical avocado sculptures constructed from dried-out avocado pits, skins, and other materials. Cheng says he ate every avocado involved. Klein describes him as “a consummate recycler.”

Another gallery displays work attributed to John Doe Co., an alter ego Cheng adopted in the late 1960s for both practical and symbolic reasons. The name originated from the advice of a tax accountant, and its corporate gloss helped him obtain industrial materials. It also served, Klein suggests, as a commentary on anonymous Vietnam War deaths, the commodification of art, and his own marginalization as an Asian American artist. Finally, it represented an homage to Marcel Duchamp and his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy. “There’s a lot of humor in Carl’s work, but at the same time there’s this kind of biting critique,” Klein says.

One John Doe Co. project was Early Warning System (1967–2024), a mechanized sculpture featuring sheaves of wheat, a radio playing maritime weather, and a projector showing human-caused natural disasters. First Generation Family Entertainment Center (1968–2020), a water tank with a motorized wave generator, LED lighting, and sound, both satirizes and replicates the allure of television. “It’s also an apt metaphor for the hypnotic glow of the screens on our phones,” Klein says. Cheng exhibited the piece at a gallery, as part of a mock living room, then marketed it at the California State Fair as a consumer product in what Klein calls a “humorous intervention” intended to highlight the ambiguity between artistic and consumerist modes of production.

Over time, Klein says, “Carl started questioning who art was for and where it was located.” One early public art initiative was Natural Museum of Modern Art (1978–80). Imitating an old-fangled automat, it allowed visitors to the Santa Monica Pier to pay a quarter and turn a dial to choose among 10 miniature dioramas made of organic materials. Gazing through a window, viewers would then observe the movement of an art tool sketching designs on a table of sand. “They had no explanation,” says Cheng. “It was quite abstract.”

A forerunner to his Santa Monica beach project, Natural Museum was inspired in part by Cheng’s travels in the early 1970s around Japan, Indonesia, and India with his longtime partner, the graphic designer Felice Mataré. In India, he says, he was struck by “people using art in public realms and not worrying about whether it was art or not.”

The ICA exhibition concludes with Art Tool: Rake 924 (1979–2024) and Human Landscapes – Imaginary Landscape 1 (2025). At each tour venue, Cheng will use the mechanized rake, which he fabricated, to sculpt a different design in sand,inviting meditations on technology, art, nature, and the idea of impermanence. The ICA landscape is a tableau of abstract symbols, evoking an alien language. “You just play around till it turns into something,” Cheng says. “What I like about it is there’s no such thing as a mistake.” —Julia M. Klein