No, the ancient Maya did not predict that the world will end in December 2012. Yes, the Penn Museum is taking advantage of the popular fascination with that distinctly North American misinterpretation of the Maya calendar to mount a wide-ranging exhibit examining Maya notions of time and much more about this rich, still-thriving culture.

By Beebe Bahrami | Illustration by Rich Lillash

Sidebar | The Maya in History

Crossing the Mesoamerican gallery on my way to interview the key players in the Penn Museum’s new exhibition on the ancient and modern Maya—MAYA 2012 Lords of Time, which runs through January 13, 2013 (assuming our world is still around then)—I see a dignified elderly docent herding a flock of three-dozen or so restless, distracted fourth graders visiting the museum on a field trip. With theatrical aplomb, the docent changes his voice so that it’s just loud enough to rise over the din of chatting and texting.

“What is going to happen when the big cycle of the Maya calendar ends in December 2012?” he says, raising one eyebrow and drawing out his words, placing particular emphasis on ends.

A hush falls over the school group. No one looks at their phones, all eyes on the prophet of the moment. A few other gallery visitors move closer. The floor perhaps trembles a little beneath our feet.

The eyebrow relaxes.

“Nothing.” He smiles innocently, his voice normal again. “A whole new long cycle will begin.”

The kids look bummed. The other visitors move on. No cataclysm? No great cosmic shift of consciousness? No John Cusack outracing the apocalypse in a battered RV? What gives?

This “package of calamity and alignment of planets” didn’t originate with the Maya at all. “It’s a North American creation,” says Loa Traxler Gr’04, curator of the exhibit and the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Associate Deputy Director. It’s hard to put your finger on exactly how the process got started, but it involved the misreading of disparate pieces of evidence that were poorly understood or interpreted outside the actual cultures from whence they came, including the Maya, to the point where the mishmash of misinformation has taken on a life of its own—a purely North American one. “These threads are from all different areas and are being bundled and linked to a calendar that has nothing to do with [them].”

Traxler should know. Her affiliation with the museum and the Maya goes back to 1989 when she began to turn her archaeological specialty toward Central America. From 1990 to 1998, she excavated every dig season at the Classic Maya city of Copan with the Penn Museum’s Early Copan Acropolis Program (ECAP), which operated from 1989 to 2003. (See the sidebar on page 44 for a primer on Maya historical periods.) She later supervised the museum’s program to publish its extensive Copan Acropolis research and oversaw publication of other monographs, as well as coordinating the Penn Maya Weekend conference before being appointed associate deputy director in 2009.

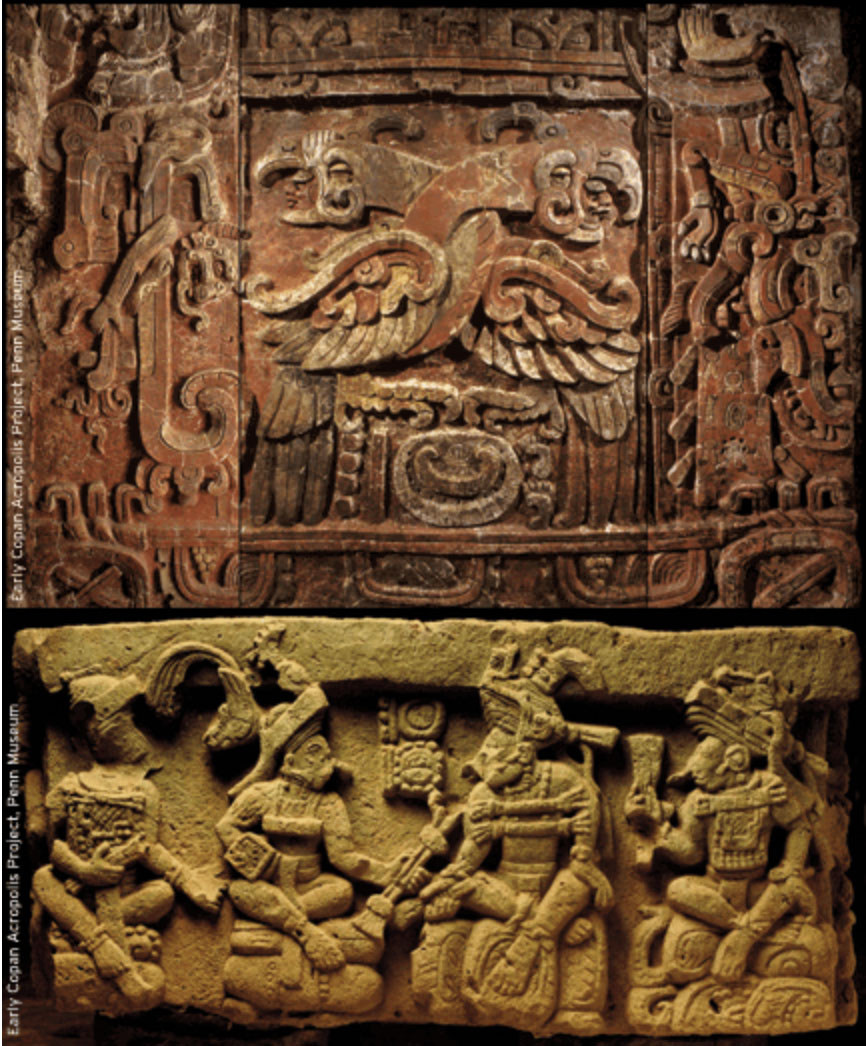

Thanks to the several decades’ long collaboration between the Penn Museum and the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (IHAH)— “the steward of Honduras’s cultural patrimony,” Traxler explains—ECAP excavations carefully dug some three kilometers of tunnels and revealed temples, palaces, and tombs containing physical remains of Copan’s royalty during its reign between 400 and 800 CE.

The Acropolis’s royal residences and temples were built on top of each other in a seemingly haphazard manner that made mapping the site more challenging. Serendipitously, the nearby Copan River had eroded portions of the eastern edge of the acropolis, offering a sneak peak of how the different sequential structures were related. This is where the team began their tunnels. (The river has since been redirected away from the archeological site.)

One of the most crucial finds was the Hunal tomb belonging to Copan’s first king, K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, who founded the dynasty in 426 CE, and the tomb of his likely queen and the mother of Copan’s second king. For Traxler, another “lifetime” find occurred in March 1992 as her two-person excavation crew was investigating a plaster floor that ran underneath a staircase.

“We decided to follow the floor as a feature and came in a short distance to where the floor had been cut into in ancient times. The cut into the floor was part of a large pit excavated in a courtyard area in the mid-6th century CE. Following down through the fill of the pit, we came upon a ceremonial offering and capstones to a tomb,” she recalls. “When one of my workmen removed a small stone wedged between the capstones, he looked within a dark opening and could see nothing but the edge of a masonry wall … With my flashlight, we were able to see an entire chamber preserved and a burial in place with many offerings.” She and her team had uncovered the completely undisturbed tomb of Copan’s eighth king, Wi’ Yohl K’inich, who ruled from 534 to 551 CE.

Seated in her modest office at the museum—decorated with prints of royal stelae (stone markers) from Copan—Traxler explains how the MAYA 2012 show hopes to leverage the buzz generated by productions like the disaster-movie 2012 to offer a more accurate picture of the Maya culture, past and present.

“It was a natural fit to take this time of attention on the Maya—whether it has any bearing on the actual Maya—and to bring people into richer engagement” with them, she says. “It’s not only on the ancient Maya but the modern Maya; it’s not only what we understand about the ancient Maya but how they continue to contribute to the world—to give voice to contemporary Maya people. We decided to focus on the Maya, their calendar, and their civilization.”

MAYA 2012 Lords of Time uses the popular and romantic notion of 2012 as a doorway into the real Maya universe—one ordered terrifically by time and observations of time through remarkably accurate astronomy, mathematics, and calendars. Like changing base metal to gold, the exhibit transforms pop-culture ideas into the truth about the fascinating Maya culture and civilization, an earthly presence of some 3,000 years and still going strong.

The museum is partnering with IHAH to mount the exhibit. More than 74 artifacts—the majority of those on display—are on loan from IHAH, supplemented by more than 50 objects from Penn’s own collection as well as materials from Harvard’s Peabody Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“This exhibition builds on the long-standing research collaboration between the Penn Museum and the IHAH,” Traxler says. “Together these institutions have carried out over two decades of research on the archaeological history of the Copan Acropolis and the royal dynasty of the ancient Copan kingdom. This generous loan of outstanding pieces from recent excavations allows the Penn Museum to showcase the collections and research of the IHAH and to promote the cultural heritage of Maya people and the nation of Honduras.”

Throughout the show’s run there will be all manner of events, from kids’ tours led by experts (such as a glyph expert, an astronomer, an archaeologist, and a conservator); to adult tours, including self-tour options narrated by Traxler and co-curator Simon Martin, an expert on deciphering, reading, and interpreting Maya texts; to lecture series. In addition, Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle will visit the Penn Museum throughout the exhibition. Agurcia is a Copan expert, Honduran archaeologist, and the executive director of the non-profit Associación Copan, a private research, education, and conservation organization dedicated to Copan and Honduras’s cultural and natural heritage. His collaboration has enriched the program of events at the Penn Museum. (For more information on programs and to order tickets, visit the Penn Museum website.)

MAYA 2012 uses calendars, monumental items, time periods, and even colors to show the passage of time. The first gallery is a dark-walled space, a “twilight” world (if you will) in which visitors will be privy to the full range of pop culture theories about the end or transformation of the world in 2012—on December 23 to be exact, the curators say, according to the nearest Gregorian reckoning of the relevant Maya calendar.

At which point, as the disappointed fourth graders learned, a new cycle starts. But not to spoil the fun too soon: among the more inventive yarns are theories about galactic alignments that may bring about the end, or that instead may offer a new beginning, a great shift of human consciousness. To offer all the evidence and set the record straight, the exhibit is fitted out with engaging panels, some called Debunkers and others Maya Misconceptions, that aim to test, tease, and educate at once.

The Debunkers ask questions (and offer answers) such as, “Did the Maya predict the end of the world? Did the Maya foresee a rare galactic alignment with disastrous results for Earth? Does the Maya calendar contain ancient predictions for the future?” And, “Are predictions for the apocalypse in 2012 different from predictions in the past?”

Likewise, Maya Misconceptions challenge popular misinformation and enticingly offer the truth. For example:

“Maya Misconceptions: The Maya recorded their calendar on a circular ‘calendar stone.’ Truth: There is no such thing as a Maya calendar stone. This was a creation of the Aztec culture.”

Part of the fun is the treasure hunt for the fascinating truth about the Maya that these panels offer.

The show’s next section deals with the Maya calendar system—which is actually several calendars, each tracking its own special relationship with celestial timing, from solar to lunar to planetary rhythms. But the one responsible for all this 2012 business is the long and largely linear calendar called the Long Count.

The Long Count’s units, called bak’tuns, are around 400 years long, and a large single Long Count cycle runs 13 cycles of bak’tun units, so about 5,125 years. Within a bak’tun are smaller units: a k’atun(approximately 20 years long), a tun (around one solar year), a winal (20 days), and a kin (a single day).

These five units, transliterated from Maya numbers into Arabic numerals, show December 23, 2012 as 13.0.0.0.0. (December 24, 2012, would be 0.0.0.0.1). It’s not unlike turning the page from December 31 to January 1, only on a much longer calendar. On December 23, 2012, a Long Count cycle is completing its 5,125 year journey, one that began around August 11, 3114 BCE.

That seems like a long time, but it wasn’t enough for the Maya. According to co-curator Simon Martin—senior research associate at the museum and associate curator of the American Section; and one of the world’s few epigraphers of Maya, specializing in deciphering, reading, and analyzing the historical records left in stone, painted on vessels, or in books—there are texts indicating that there are at least 19 more names demarcating even higher time places on the Long Count, above the 5,125 year cycles.

This idea of time cycles greater than five thousand years reverberates in my head. What does that mean? I finally ask.

That rather than time stopping, he says, “it goes on for up to trillions of years.”

Which sounds rather optimistic to me.

“The Maya didn’t associate the Long Count with apocalyptic ideas,” Traxler says. “They did acknowledge destruction, but not in the Long Count. They didn’t see the end of the bak’tun as the end—it just completed it—and then started [a new] bak’tun.”

Once visitors have learned that all the Long Count was really doing was tracking time, long stretches of it, and marking the end—and the beginning—of cycles, based on astronomical observations, they enter the ancient Maya world as seen at Copan. Here, the exhibit’s wall colors shift to the palette of a dawning day, and the focus is on who the ancient Maya really were—and who they were not (namely, Aztec and Inca).

Copan offers a particularly compelling case study of the Classic Maya period (250-900 CE), when the civilization was characterized by city-state polities with extensive trade relationships and complicated, hierarchical social and political organizations, ruled by dynastic kings who inherited their role as semi-divine leaders of their community—aka the “Lords of Time.”

Copan is remarkable for many reasons, and not least because it offers a nearly complete archaeological and historical documentation of the Classic Maya from around 400 to 800 CE, from the city’s beginnings to its decline. Rarely do archaeologists discover a site that is undisturbed enough to afford a complete survey of its existence, from its founding to its abandonment.

“The fact that I can stand in the West Court of the Copan Acropolis and truly envision the evolution of that location over generations of kings and queens, complete with their ceremonial buildings, artistic programs, and remains of their lives, is a remarkable feeling as an archaeologist,” says Traxler. “Few locations offer the same richly detailed history in the Americas.”

MAYA 2012 conveys the drama of being at Copan by replicating several pieces of life-size monumental architecture that were too large to transport from Honduras. Notable among these are the Margarita Panel and Altar Q, which are something of the alpha and omega of monuments at Copan. Measuring nine feet high and 12 feet wide and carved around 450 CE, Margarita commemorates Copan’s first ruler, while Altar Q was dedicated in 776 CE by the last king of Copan to the founder of the dynasty 348 years earlier. The remarkably well-preserved Margarita Panel, found buried deep within the Copan Acropolis, shows the name of the king (K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’) as represented by an intertwined quetzal bird (K’uk) and scarlet macaw (Mo’), with crest elements that mean first or green (Yax). Altar Q has a portrait of each king, with his name and reign, in a chain of succession. The founder hands the scepter to the 16th king, while the founder’s son, the second king, sits behind his father, and behind him, the third king, and so forth. It is an archaeological gem but also a mythmaking piece, bringing these 16 rulers to life.

Subsequent galleries introduce the Maya of today in their own voices—in Mayan and Spanish with English subtitles—through videos gathered by Traxler while on the ground in Central America.

Today, some 10 million Maya live all around the globe, with the largest populations in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, and El Salvador. The videos offer Maya perspectives on the world today and their place in it, as well as Maya views of 2012.

“We decided to use the hook of 2012 in popular culture to bring people in and to teach about the Maya,” says Kate Quinn, the Penn Museum’s director of exhibitions. “Throughout there will be expert kiosks, five experts on the Maya and six experts who are Maya. Part of the exhibit’s strength is it allows modern Maya to tell their experience in their own voices.”

The exhibit also has kiosks where visitors can learn about Maya glyphs, spell their names using them, and interactively investigate the numerical system (including working out their birthdays on the Maya calendar).

Quinn, who came to Penn from the Delaware Art Museum in 2008, has an extensive background in theater, film, and exhibit design and has worked with cultural materials for exhibits from all around the world, including the recent Penn Museum exhibits Secrets of the Silk Road [“Ancient Secrets, Found and Shared,” Jan|Feb 2011] and Iraq’s Ancient Past. Asked to name the highlight of working with the Maya materials, she says, “I can see the Maya better because I’m an artist and they are so visual. They are so expressive and visual it’s amazing.”

Traxler suggests that this may be a part of the general fascination with the Maya. “The artwork blends together a very humanistic and naturalistic quality, such as in the faces, and at the same time it’s bound with extremely complex and dynamic symbolism.”

She points overhead to a large image of a royal stela on her office wall. “For example, take a king’s portrait,” she says. “He’s regal and is holding up a sky bar and all around him swirls all this iconography and yet at the center is a very real human face. It’s exotic and at the same time recognizable.”

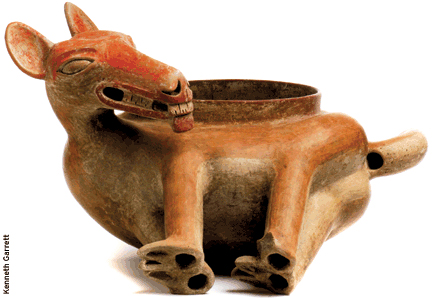

One of the objects on display that vividly demonstrates this is the lid of an incense burner, or censer, depicting Copan’s dynastic founder, K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, who ruled from 426 to 437 CE. It shows a very hip-looking fellow by modern aesthetics, who today could be taken as a famous rapper, movie star, or daredevil pilot. His eyes are covered by what appear to be goggles or Gucci sunglasses, but which are in fact shell rings that, to the Classic Maya, represented a warrior. Along with other tomb finds related to K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, the object is a reminder that, back in the 5th century, it took some serious moxie to found this remarkable city-state, requiring the skills of a strategic warrior and politician who could also demonstrate his favorable standing among the gods.

The Maya also fascinate because of their intricate and complex culture, one that made accurate astronomical calculations using the naked eye; had a complex mathematics and numerology system; and constructed remarkable architectural monuments, cities, trade networks, transport systems, and irrigation systems.

Perhaps most stunning of all, “the Maya developed the only comprehensive writing system in the New World that we can read,” Martin adds. “In the New World, we have what the Spanish said about the Inca, the Aztecs, and a little about the Maya, and beyond that we have archaeology. With the Maya we have an inverted situation where we can now read what they have to tell us about themselves over 2,000 years.”

The Maya have always been great observers of time and the skies, as their mathematics, numerology, and astronomy attest. During the Classic period, Maya royalty used the Long Count as an instrument to weave themselves significantly into great stretches of time, but many other calendars are cyclical and shorter and have been in use from ancient times to the present. Among the most important are the Sacred Calendar, a cycle of 260 sacred days, and the Haab, a largely solar calendar of 365 days. Other calendars were based on the movement of other celestial bodies, such as the moon, Venus, and other planets.

MAYA 2012 elegantly demonstrates these systems graphically. The exhibit also clearly shows that the Maya were profoundly interested in the cosmic timing of everything, in the skies and in earth-bound affairs. Indeed, the sky and earth, as well as the underworld, were all connected in one great cosmic orchestration.

“The Maya loved numerology and were fascinated by temporal interconnections and intricacies of representing time,” says Traxler. “The exhibit highlights the Long Count calendar and its uses during the Classic period—and that it is the most formal way to represent time. It is written in extremely formal language. It would be like opening up a formal invitation and it being written—time included—in a very formal language. The Long Count was how Maya kings wrote about time. It was primarily used by kings to describe their place in time.”

A particularly important day on the Sacred Calendar was the day with the day sign Ajaw, which is not only a day sign but also the Maya word for king or lord. When an Ajaw day intersected with an important day on the Long Count and the Haab, kings took note. “The day signs were like ours, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, King, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, for example,” Martin explains. “Every time the day is Ajaw, they [the kings] would like to tell you. Any cycle worth its name ended in zero, and it is the day of King/Lord.”

The calendar was how a king expressed himself as a Lord of Time. “He was a part of the order of the cosmos,” says Traxler. “The king was exalted and the representative of the community. The king was semi-divine, but both representative [for the community] and able to intercede with the spiritual world and to help protect in relation to the cosmos, with the gods of the underworld.”

If the king interceded successfully, the majority could continue to thrive, to plant and harvest, gather and trade, build and create. It was a symbiotic relationship where each side—the royal elite and the majority non-elite—upheld their end of the bargain, so long as the cosmos backed the king.

The auspicious moment in 435 CE when Copan’s founder and his son celebrated the end of the ninth and the beginning of the 10th bak’tun of the current bak’tun cycle is recorded in two stone monuments at Copan, the Motmot Marker and Stela 63. The language speaks of their success in seeing this cycle of time through to fruition and the beginning of a promising cycle. There, they weren’t wrong. Copan would flourish for almost another 400 years. But there was no similar commemoration of the transition from the 10th to the 11th bak’tun—by then, the city-state was already in decline.

Commemorative events between bak’tun cycles often occurred in periods of 20 years, sometimes 10. Called a k’atun ending ceremony, these functioned more or less as a 20-year review, an opportunity to look back and reflect, “Hmm, seems like the events fulfilled that prophecy, right on. The gods are still working with us.” It was a way of keeping track of prophecies and understanding how they manifested, and that they did, and that the king had managed to hold his effective role as intermediary between the divine and mortal realms. Part of the reason for the decline of the dynasty around 820 CE was the advent of natural and human-induced disasters that made it appear that the kings were ineffective: the 20-year review didn’t look so good.

While the Long Count fell out of use more than a thousand years ago, time is still quite important to the Maya. In traditional areas the Sacred Calendar and the solar calendar are still crucial for picking dates to build a house, get married, or celebrate other important life passages. Moreover, Daykeepers—Maya shamans—are engaged with time as a guide to important individual and community rituals.

Even though the Maya don’t share North American delusions about 2012, that doesn’t mean the December date will go unnoticed in the Maya world. To the contrary, 2012 is planned as a celebratory year of the Maya culture, with festivities, tours, and exhibits planned throughout Central America. These celebrations are especially pronounced in areas where Maya culture is rebuilding its vitality after centuries of colonial and post-colonial silencing.

Among the Maya today, says Traxler, “there is continuous use of the Sacred Calendar in ceremony and divination because it’s still encapsulated by divining specialists [Daykeepers] and related to divination practices, such as asking, ‘What’s the right day to marry, to build a house.’ It’s still in use like this in really traditional communities.”

She smiles. “And then there are Maya here or there who keep track of time with their cell phones, like a lot of us. For most Maya, 2012 is hopefully a really good year. It’ll be like New Year’s.”

Beebe Bahrami Gr’95 is a widely published writer and anthropologist and frequent contributor to the Gazette. Fascinated as much by the ancient past as the unpredictable present, she is at work on a time-traveling memoir, Café Oc, excavating southwestern France’s past and present.

SIDEBAR

The Maya in History

Archaeologists and historians regard the sweep of the Maya’s dynamic past in terms of the Preclassic, the Classic, and the Postclassic periods.

The Preclassic stretches from somewhere around 1000 BCE, before the time of the Maya kings, to about 250 CE.

The Classic period, from around 250 CE to 900 CE, is considered the point when the Maya civilization exhibited the most social hierarchy, with the rise of elite minorities governing over non-elite majorities, as well as the most architectural, artistic, and written output, the largest population centers, trade networks, and dynastic centers. “There was class division,” says MAYA 2012 co-curator Simon Martin, “and it was hierarchically organized. Everyone had a sense of place and it was very rigid.”

This was the time of city-states such as Copan, Palenque, and Tikal. The Classic period in Maya history is the apex of the ancient Maya universe expressed in complex and stunning astronomy, mathematics, calendrical systems, architectural and agricultural feats, trade networks, and complex political, social, and cultural systems.

A lot about the Maya can be understood through this window, one where the Long Count calendar was in full use, the very calendar whose misinterpretation by us moderns has got us in this 2012 bind.

The Postclassic period (900 –1500 CE) describes the aftermath of both natural and human-induced decline of these dynastic Classic centers when overpopulation, environmental degradation, a long period of recurring droughts, crop failures, famines, and deaths from diseases and violent conflicts emptied the cities.

Traxler explains that we can view the Postclassic as an era of transformation. The Maya actually recovered from the natural and human-made disasters and opened up new and wider trade with other Mesoamerican peoples, creating a more pan-Central American network of trade and influences between the Maya and non-Maya world. They also developed new crafts and established less hierarchical communities.

With the decline of the dynastic centers, the Long Count stopped being used because it was really the device of the kings and equated with them and their time of power on earth. The last known Long Count date comes from a stela at Toniná, Mexico, carved with the date 909 CE. But time did not cease just because the Long Count stopped being employed. The many other calendars, especially the two all-important Sacred Calendar and Haab (solar) continued, and time tracking was still important, as it remains today in traditional Maya communities.

From European contact around 1500 to the present, not only have the Maya persisted in their distinct language and culture, but they are in the midst of a serious cultural flourishing after centuries of suppression. Martin thinks that this success may in part have been from the lucky circumstance that “the Maya area didn’t have gold and that might have helped keep their culture intact with [Spanish] contact.” Language also plays an important role. “Language is the best continuing and defining characteristic of the Maya. They have a strong sense of identity [through] language [and] art styles, and [these] make a strong distinction between themselves and other [Central American peoples].”

The exhibit gracefully elaborates on these time periods, from the ancient, to contact and colonization, to the modern era where some 10 million Maya live in the world today, mostly in Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Belize, and El Salvador, but many in immigrant communities throughout the world, including Philadelphia.

—B.B.