Francis Hopkinson signed the Declaration of Independence, designed the American flag, wrote some biting satire, composed the nation’s first secular music, and got some props for his scientific ingenuity. Not a bad career for the College’s first alumnus.

By Samuel Hughes | Illustration by David Hollenbach

Sidebar | Designs for Wine and Country

Sidebar | From Bluecoat to Redcoat, a Turncoat

Podcast | “The Battle of the Kegs,” by Francis Hopkinson. Read aloud by Samuel Hughes.

December 16, 1776. War has come to the rebellious American colonies. The Hessian Jäger Corps has marched into Bordentown, New Jersey, a small town on the Delaware River just northeast of Philadelphia. Captain Johann Ewald, the regiment’s commander, enters a handsome brick house known to belong to a prominent rebel. Its library is filled with numerous pieces of “scientific apparatus”—and, of course, lots of books. One, titled Discourses on Public Occasions in America, by the Rev. William Smith—the provost of the College of Philadelphia and a staunch, though nuanced, Loyalist—catches Ewald’s eye, and he plucks it from the shelf. After riffling through the pages he takes a pen and writes, in German and beneath the bookplate of the book’s owner:

“This man was one of the greatest Rebels, nevertheless, if we dare to conclude from the library and mechanical and mathematical instruments, he must have been a very learned Man also.”

The learned rebel was Francis Hopkinson C1757 G1760 Hon1790, a member of the first graduating class of the College of Philadelphia, which would soon become the University of Pennsylvania. Most of the mechanical instruments had been lent to him by the College’s founder, Benjamin Franklin, who would later bequeath them all to Hopkinson and make him an executor of his will.

Being described as “one of the greatest Rebels” must have been quite the compliment to the diminutive, delicate-featured Hopkinson. Consider the description of him by John Adams four months earlier in a letter to his wife, Abigail. Having just met Hopkinson at Charles Willson Peale’s art studio, Adams described him as a “painter and a poet” who had been “liberally educated,” adding:

I have a curiosity to penetrate a little deeper into the bosom of this curious gentleman, and may possibly give you some more particulars about him. He is one of your pretty, little, curious, ingenious men. His head is not bigger than a large apple … I have not met with anything in natural history more amusing and entertaining than his personal appearance; yet he is genteel and well-bred, and is very social.

Adams harrumphed a bit about not having the “leisure and tranquility of mind to amuse myself with these elegant and ingenious arts of painting, sculpture, architecture, and music,” though he acknowledged that a “taste in all of them is an agreeable accomplishment.” All in all, his tone seems a bit condescending, perhaps, and a bit unfair. Hopkinson would serve his country ingeniously and bravely in the coming years, even if he didn’t carry a musket. Having already signed the Declaration of Independence as a member of the New Jersey delegation to the Continental Congress, Hopkinson would serve as the de facto secretary of the Treasury and the de facto secretary of the Navy (neither of those positions officially existed yet) and as a judge of the Admiralty (a position from which he was impeached and then completely exonerated). He would later be appointed to the federal bench by President George Washington; be called a “man of genius, gentility, & great merit” by Thomas Jefferson; and be praised by Robert Morris, the new nation’s financier-general, as a “Gentleman of unblemished Honour & Integrity, a faithful and attentive Servant of the Public and steadily attached to the American cause.”

While Adams’ suggestion that Hopkinson’s talents were essentially artful is on-target, those artistic contributions were fired by a very real patriotism. His talent for graphic design resulted in such iconic images as the American flag (see p. 53) and (though he wasn’t the main designer) the Great Seal of the United States—not to mention the Orrery Seal for his alma mater.

Hopkinson was also the first American-born composer of secular music. His “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free,” written in 1759, is believed to be the first secular composition in the country (or at least the first written down), while his “The Temple of Minerva,” celebrating the alliance between France and the United States, is considered, in the words of one critic, America’s “first attempt at grand opera.”

Famous in his day for his literary wit, Hopkinson churned out satirical poems and parables like “A Pretty Story” (a sort of colonial American precursor to Animal Farm); “A Prophecy: Written in 1776” (an allegorical response to the Loyalist warnings of Provost Smith); and “The Battle of the Kegs,” a puckish nose-thumbing at the occupying British that went viral, at least by 18th-century standards.

“I have not the abilities to assist our righteous Cause by personal Prowess & Force of Arms,” he would write in a letter to Benjamin Franklin, “but I have done it all the Service I could with my Pen—throwing in my Mite at Times in Prose & Verse, serious and satirical Essays, etc.”

This was no small contribution. Dr. Benjamin Rush, the “father of American psychiatry” who taught chemistry at the College and practiced medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital, put it this way: “the various causes which contributed to the establishment of the Independence and federal government of the United States, will not be fully traced, unless much is ascribed to the irresistible influence of the ridicule which [Hopkinson] poured forth, from time to time, upon the enemies of those great political events.”

Hopkinson was just 14 when his father died in November 1751. Thomas Hopkinson had been a founder and trustee of the Academy of Philadelphia (the secondary-school precursor of the College), and earlier that year he had enrolled Francis as its first student. The senior Hopkinson had been a good friend of Franklin, who mourned his passing in The Pennsylvania Gazette and looked after his family for many years. He took a particular interest in Francis, and despite the age difference, the two would be friends until the end of their lives. (In congratulating Hopkinson on his appointment as treasurer of loans during the Revolution, Franklin wrote: I think the Congress judge’d rightly in their choice, as Exactness in accounts and scrupulous fidelity in matters of Trust are Qualities in which your father was eminent, and which I was persuaded was inherited by his Son …)

Two of Hopkinson’s classmates in that first College class would become his brothers-in-law. One sister married Jacob Duché (class valedictorian, professor of oratory, Anglican minister, and eventual turncoat—see p. 54); another married John Morgan, who organized the medical department of the College and served as director general and physician-in-chief to the general hospital of the Continental Army.

Hopkinson was apparently one of Provost Smith’s star pupils, and became, along with Duché, part of a poetic group that called themselves the Swains of the Schuylkill. In November 1754 he gave a public address titled “On Education in General,” noting that “whether the Design be to preserve a good Constitution … or to mend a bad One, and secure it against all Dangers from without, it is only to be done effectively by the slow, but sure Means of a proper education of youth.”

A bad constitution in need of mending might seem to suggest the stirrings of a young revolutionary, but Hopkinson, like most people affiliated with the College in those days, was still quite loyal to the British Crown. He contributed an essay to a book published by Smith titled The Reciprocal Advantages Arising From Perpetual Union Between Great Britain and Her American Colonies, and at the Commencement of 1762 delivered an “Ode on the Accession of His Present Gracious Majesty, George III,” which might charitably be described as blandiloquent.

Less than a year later, he published some caustic verses ridiculing a Latin grammar that had been written by his former Latin professor, John Beveridge. To make things worse, the printing of the grammar had been overseen by Vice-Provost Francis Alison. “Errata, or the Art of Printing Incorrectly” included the following lines: “When Mr. Beveridge took his Pen in hand/ What for to write he did not understand/ He then invok’d his Muse in plaintive strain,/ His Muse obey’d & fill’d his plodding Brain/ The Time of Labor comes—but then alas!/ The filthy Offspring proves to be an Ass/.” When Beveridge wrote a satirical reply in Latin; Hopkinson fired off another poetic salvo.

The offending verses, noted Thomas Haviland in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, “directly resulted in action by the vice-provost and the Latin professor which prevented Hopkinson—a steady contributor of music and odes for some time after his graduation—from taking part in the Commencement of 1763, to the consequent impoverishment of those festivities.”

But the College soon relented. In May 1765 the trustees wrote that “as the first scholar in this seminary at its opening, and likewise one of the first who received a degree, [Hopkinson] has done honor to the place of his education by his abilities and good morals, as well as rendered it many substantial services on all public occasions.” Therefore, they added, “the thanks of this institution ought to be delivered to him in the most affectionate and respectful manner.”

Throughout his life Hopkinson had a keen interest in scientific matters, and in 1762 he dedicated his lengthy poem “Science” to the trustees, provost, and faculty of the College. He would later collaborate with David Rittenhouse on “An Account of the Effects of a Stroke of Lightning on a House Furnished with Two Conductors,” and receive the first Magellanic Prize from the American Philosophical Society for his invention of a “spring-block designed to assist a vessel in sailing.”

“I have your Gimcrack Instruments in safe Preservation, & they afford me great Amusement,” Hopkinson told Franklin in 1781. “I have many new Ideas floating in my Brain, in Consequence of the Experiments I make; but have not Time, or what is more likely, not Genius sufficient to form them into a System for your Amusement.”

For all his interest in Gimcrackery and the arts, Hopkinson needed a day job, and for most of his life that would involve the law. (That he had no illusions about the profession is clear from a couplet he dashed off in Chester: “Attorneys and clients here lovingly meet,/ The one to be cheated, the other to cheat.”) After studying under Benjamin Chew, Pennsylvania’s attorney general, Hopkinson hung out his shingle in 1761. That year he was appointed to a new Indian Commission charged with making a treaty with eight tribes of Native Americans. He transmuted his experiences at the treaty conference in Easton, Pennsylvania into “The Treaty,” a long poem that sounds like something out of The Sot-Weed Factor. (“See from the throng a painted warrior rise,/ A savage Cicero, erect he stands,/ Awful, he throws around his piercing eyes,/ Whilst native dignity respect commands.”)

Hopkinson’s romantic streak showed itself before he started writing rhapsodic love poems to Ann Borden, whom he would marry in 1768, and with whom he would have five children. (One of his sons, Joseph Hopkinson C1786 G1789, attended the College, served as a trustee, became a federal judge and a US Congressman, and wrote the lyrics to “Hail Columbia.”) In 1764 Hopkinson and several other gallant fellows helped a young woman named Betty Shewell escape from the Philadelphia room where her brother had locked her up for accepting a marriage proposal from the painter Benjamin West, who was then living in England. After descending by rope ladder, she was taken by a waiting carriage to Chester, where she boarded a ship for London. Hopkinson’s co-conspirators, incidentally, were an unlikely group: Benjamin Franklin, the future Bishop William White (then 18), and—according to some accounts—Provost Smith, who later complained that West had never thanked him or acknowledged his role in the escapade.

When Hopkinson traveled to Britain two years later, he stayed with West (a friend since his College days) and his bride. That trip prompted the first hint of a social consciousness in Hopkinson, who was shocked by the appalling conditions of the Irish peasantry: “All along the road are built the most miserable huts you can imagine of mud & straw, much worse than Indian wigwams, & the miserable inhabitants go scarce decently covered with rags—the poor are numerous & very indigent indeed.” While no one among the “lower class in Pennsylvania” lacks the comforts of life “who hath health & industry,” he added, “many of the poor here cannot obtain the necessities of it.”

Hopkinson was unable to secure a sinecure in England despite a glowing letter to the Bishop of Worcester from Franklin, who described him as a “very ingenious young man” and praised his “good Morals & obliging Disposition.” When he returned to Philadelphia he opened up a dry-goods business that also offered “choice Port wine,” and in 1772 Lord North appointed him Collector of the Customs for New Castle, Delaware. (Hopkinson already had a similar post for Salem, New Jersey.) That patronage did not stop him from penning increasingly pointed anti-Tory essays and allegories, however. Eventually, despite the need to provide for his young family, he would resign from those jobs.

As the First Continental Congress was opening its first session in August 1774, a Philadelphia printer named Peter Dunlop published a 76-page allegory by “Peter Grievous, Esq., A. B. C. D. E.” Titled “A Pretty Story,” it told the tale of a “certain Nobleman, who had long possessed a very valuable Farm” and who was married to a succession of wives (think Parliament) chosen by his children and grandchildren. The old nobleman had “obtained a Right to an immense Tract of wild uncultivated Country at a vast Distance from his Mansion House,” and there some of his “more stout and enterprising” children had settled.

Eventually, problems arose: “the Nobleman’s Wife began to cast an avaricious Eye upon the new Settlers” and passed a series of odious acts, including a tax on “Water Gruel,” which the settlers refused to unload and otherwise let spoil. Finally a settler named Jack “stove to Pieces the Casks of Gruel … and utterly demolished the whole Cargoe.”

The old nobleman “fell into great Wrath,” and his wife “tore the Padlocks from her Lips, and raved and stormed like a Billingsgate,” while the Steward swore “most profanely” that he would humble the settlers. A “very large Padlock” was fastened upon Jack’s gate, which could not be opened “until he had paid for the Gruel he had spilt, and resigned all Claim to the Privileges of the Great Paper” (aka the Magna Carta). To drive the point home, a “large Gallows was erected before the Mansion House in the old Farm.”

When the other settlers supported Jack and his family, sneaking food to them and advising them “to be firm and steady in the Cause of Liberty and Justice,” the steward responded with a “thundering Prohibition” declaring any meetings to be “treasonable, traitorous and rebellious.” The tale ended on the following note: “These harsh and unconstitutional Proceedings irritated Jack and the other inhabitants of the new Farm to such a Degree that *****”—followed by the Latin words Cetera desunt. (“The rest is wanting.”) In other words, Stay Tuned.

Hopkinson’s wit “flashes upon every legal question then at issue,” wrote Moses Coit Tyler, author of The Literary History of the American Revolution, and “A Pretty Story” established him as “one of the three leading satirists on the Whig side of the American Revolution.” (Unlike the other two, John Trumbull and Philip Freneau, Hopkinson “accomplished his effects without bitterness or violence.”)

Some in Philadelphia knew that Peter Grievous was Francis Hopkinson. “But to the members of the First Continental Congress, who did not know of this local wit and satirist, the story simply was an amazing allegorical account of England and the colonies,” noted George Nichols Marshall in Patriot with a Pen. “Many delegates at the Congress bought copies to mail home, and soon editor after editor began publishing it as a serial in local newspapers.”

Long before the Revolution, Benjamin Franklin and William Smith, the founder of the College and his hand-picked provost, had fallen out [“Your Most Obedient Servant: The Provost Smith Papers,” April 1997]. For some years after his graduation, Hopkinson was able to stay friends with both. But when it came time to take a stand, Hopkinson emphatically sided with Franklin.

In “A Prophecy: Written in 1776” Hopkinson used a Biblical style to tell his story about a “new people” in a “far country,” who will soon be given a tree by the “king of islands.” But a certain “North wind” will arise and “blast the tree, so that it shall no longer yield its fruit, or afford shelter to the people, but it shall become rotten at the heart …” Then, he wrote:

a prophet shall arise from amongst this people, and he shall exhort them, and instruct them in all manner of wisdom, and many shall believe in him; and he shall wear spectacles upon his nose; and reverence and esteem shall rest upon his brow.

Just how much Franklin influenced Hopkinson’s opinion of Smith is impossible to say, but the bottom line is that Hopkinson had no qualms about penning some harsh words about his old provost—whose series of letters signed Cato had warned Pennsylvanians that they had “much to lose in this contest.” (Those letters were themselves a response to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense.”) In Hopkinson’s “Prophecy,” the man who called himself Cato

shall strive to persuade the people to put their trust in the rotten tree, and not to dig it up, or remove it from its place. And he shall harangue with great vehemence, and shall tell them that a rotten tree is better than a found one; and that it is for the benefit of the people that the North wind should blow upon it, and that the branches thereof should be broken and fall upon and crush them.

And he shall receive from the king of the islands, fetters of gold and chains of silver; and he shall have hopes of great reward if he will fasten them on the necks of the people, and chain them to the trunk of the rotten tree … And his words shall be sweet in the mouth, but very bitter in the belly.

In case the point wasn’t clear, Hopkinson concluded:

And Cato and his works shall be no more remembered amongst them. For Cato shall die, and his works shall follow him.

By the winter of 1777-78, things were looking pretty grim for the American cause. General William Howe’s British troops occupied Philadelphia, and George Washington’s soldiers were freezing and dying at Valley Forge. The rebellious spirits badly needed a lift.

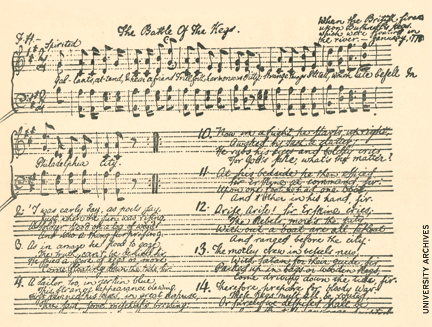

On January 5, a flotilla of kegs, filled with gunpowder and designed to explode on contact with anything they bumped into, was pushed into the Delaware River from a point several miles north of Philadelphia. (The plan was conceived and executed by David Bushnell, the inventor of the first American submarine and other aquatic weapons, though Hopkinson—then chairman of the Continental Navy Board’s Middle Department—and his father-in-law, Joseph Borden, probably had a hand in the operation.) The kegs didn’t hit any of the British ships anchored in the Delaware on account of all the ice, but they did explode—apparently killing at least one curious boy—and drew fire from some of the British troops.

Shortly after the event, a suspiciously tongue-in-cheek prose account of the episode appeared in local newspapers:

“Some reported that these kegs were filled with armed rebels, who were to issue forth in the dead of night, as did the Grecians of old from their wooden horse at the siege of Troy, and take the city by surprise,” the author claimed, “whilst others asserted they … would, of themselves, ascend the wharves in the night-time, and roll all flaming through the streets of the city, destroying every thing in their way.”

From the British warships, “whole broadsides were poured into the Delaware,” and “not a wandering chip, stick, or drift log, but felt the vigor of the British arms.” That day, the writer concluded, “must ever be distinguished in history for the memorable battle of the kegs.”

The anonymous writer was almost certainly Hopkinson, who used the final phrase as the title of the 88-line satirical poem that would be published in The Pennsylvania Packet on March 4.

“The Battle of the Kegs,” which even referenced Howe’s married Philadelphia mistress, “soon was read in papers all over the colonies, memorized by regimental bards and barroom buffoons,” noted George Marshall. “The account of the ridiculous British navy fighting an unseen enemy in the Delaware burst the seams and tickled the funny bones of the colonists.”

PODCAST: “The Battle of the Kegs,” by Francis Hopkinson.

Read aloud by Samuel Hughes.

Hopkinson’s merriment was only temporary, as in May of that year, another troop of British soldiers marched into Bordentown, and this time they pillaged his house and burned that of his father-in-law.

“I have suffered much by the Invasion of the Goths & Vandals,” Hopkinson wrote to Franklin, then in France. “The Savages plundered me to their Hearts’ content—but I do not repine, as I really esteem it an honour to have suffered in my Country’s Cause in Support of the Rights of human nature and of civil Society.”

Hopkinson enclosed the “The Battle of the Kegs” and another satirical piece titled “Date Obolum Belesario,” to which Franklin replied: “I thank you for the political Squibs; they are well made. I am glad to find such plenty of good powder.”

The poem became even more popular once it was set to music. By July 10, 1780, Continental Army Surgeon James Thacher was writing in his journal about a festive evening near Passaic Falls in New Jersey: “Our drums and fifes afforded us a favorite music till evening, when we were delighted with the song composed by Mr. Hopkinson, called, the ‘Battle of the Kegs,’ sung in the best style by a number of gentlemen.”

On December 11, 1781, less than two months after the decisive Battle of Yorktown, a musical work titled “The Temple of Minerva, An Oratorial Entertainment” was performed in Philadelphia. Among those in attendance were Anne-César De la Luzerne, the French Ambassador to the United States; General and Martha Washington and General Nathanael Greene; and Hopkinson, the composer of the work. Originally titled “America Independent,” the work was a “dramatic allegorical cantata,” in the words of musical historian Oscar Sonneck, who called Hopkinson “America’s first poet-composer.”

Set in front of the Temple of Minerva (the goddess of wisdom), the cantata’s three male figures—the Genius of France, the Genius of America, and the High Priest of Minerva—prayed for the goddess to appear and make a prediction about the new nation of Columbia. When she made her entrance in Act II, Minerva predicted that a happy state would repay all of Columbia’s grief, and that if her sons would stand united, “great and glorious shall she be.”

The outcome of the war was still very much in doubt when Hopkinson composed “The Temple of Minerva,” which gave its cautiously optimistic words an even sweeter ring when performed before the victorious generals. But while a review in The Freeman’s Journal the following week said that the performance “afforded the most sensible pleasure,” the Tory response can be gleaned from a parody published in the January 5, 1782 issue of the Royal Gazette: “The Temple of Cloacina: An Ora-whig-ial Entertainment.” In that version—which consisted of a severely pencil-edited copy of the original—the temple was an outhouse. In a lengthy 1976 article for the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, musicologist Gillian B. Anderson described the entire parody as shockingly obscene.

Hopkinson himself told Benjamin Franklin that “The Temple of Minerva” was “not very elegant Poetry, but the Entertainment consisted in the Music & went off very well.” Since the music consisted of works by Handel and other composers as well as his own, he explained, he had to tailor his lines around their works. “In short, the Musician crampt the Poet.”

Whatever the critical assessments of Hopkinson’s music, we know that it sometimes had a strong effect on listeners. When he sent a collection of his popular songs to Thomas Jefferson, then the US Ambassador to France, Jefferson responded that “while my elder daughter was playing [one song] on the harpsichord, I happened to look toward the fire, & saw the younger one all in tears. I asked her if she were sick? She said, ‘No; but the tune was so mournful.’”

Hopkinson later sent a copy of his song book to Washington, with the following comment:

However small the Reputation may be that I shall derive from this Work, I cannot, I believe, be refused the Credit of being the first Native of the United States who has produced a Musical Composition. If this attempt should not be too severely treated, others may be encouraged to venture on a path, yet untrodden in America, and the Arts in succession will take root and flourish amongst us.

Washington’s answer was both generous and diplomatic. While he himself could “neither sing one of the songs, nor raise a single note on any instrument to convince the unbelieving,” he wrote, he could offer “one argument which will prevail with persons of true taste (at least in America)—I can tell them that it is the production of Mr. Hopkinson.”

Hopkinson’s contributions to the American cause didn’t end with the Revolution. By the crucial year of 1787, he had become a firm Federalist. In that arena, true to form, he’s probably best known for “The New Roof,” the allegorical essay and poem he wrote about replacing the Articles of Confederation with a new constitution. (The poem was originally titled “The Raising: A New Song for Federal Mechanics.”)

The gist of the prose version goes like this: Despite being only 12 years old, the “roof of a certain mansion house” had decayed so badly that it could no longer provide protection from the weather. When a group of “skillful architects” examined it, they found that the “whole frame was too weak”; that its 13 rafters were “not connected by any braces or ties so as to form a union of strength”; that “some of these rafters were thick and heavy, and others very slight”; that the “lathing and shingling had not been secured with iron nails but only wooden pegs,” which would shrink and swell in the sun and rain—causing the shingles to become “so loose that many of them had been blown away by the winds.” Finally, the roof was “so flat as to admit the most idle servants in the family, their playmates and acquaintances, to trample upon and abuse it.”

In order to build a new and better roof, the architects “consulted the most celebrated authors in ancient and modern architecture” and tried to “proportion the whole to the size of the building and strength of the walls.” (The validity of his imagery is still debated; in a recent essay titled “A Roof without Walls: The Dilemma of an American National Identity,” historian John Murrin wrote: “Francis Hopkinson to the contrary, Americans had erected their constitutional roof before they put up the national walls.” But that’s another story.)

“The New Roof” was widely read and well received in its day—though again true to form, Hopkinson’s potshots at the Anti-Federalist camp (too complicated to go into here) sparked some return fire. One opponent called him a “base parasite and tool of the wealthy and great, at the expense of truth, honor, friendship,” and added: “Little Francis should have been cautious in giving provocation, for insignificance alone could have preserved him the smallest remnant of character.”

Hopkinson had the last laugh, though. On July 4, 1788, Philadelphia—which had waited until 10 states had ratified the Constitution—celebrated with a “Grand Federal Procession” that was both wildly propagandistic and a spectacular success. Hopkinson himself, the Grand Marshal, planned and directed the whole event. Its 87 divisions consisted of floats, allegorical figures, and groups; bands and military organizations; state, national, and foreign officials; delegations from various societies; and representatives of trades and professions ranging from stone-cutters and farmers (motto: “Venerate the Plough”) to gun-smiths and sugar refiners (“Double Refined”).

“The rising sun was saluted with a full peal from Christ Church steeple,” wrote Hopkinson, followed by a “discharge of cannon from the ship, Rising Sun … anchored off Market Street, and superbly decorated with the flags of nations in alliance with America.” About 5,000 people marched or rode in horse-pulled floats in the procession itself, which started at Third and South streets and arrived at Union Green, part of the Bush Hill estate north and west of 12th and Market. Franklin, then president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, was “too much indisposed” to attend, but Hopkinson marched in a division representing the state’s Court of Admiralty, which he knew would be made obsolete by the Constitution. The chief justice of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court rode in a 13-foot-tall bald eagle, its breast emblazoned with 13 silver stars and its talons clutching an olive branch and 13 silver arrows. (Eat your heart out, Stephen Colbert.) “Students of the university, headed by the vice-provost,” marched with representatives of the city’s other schools, holding a small flag inscribed The Rising Generation, Hopkinson noted, while at the end of the procession marched lawyers, physicians, and “the clergy of the different Christian denominations, with the rabbi of the Jews, walking arm in arm.”

And the most imposing float in the procession was the “New Roof, or Grand Federal Edifice,” designed by Charles Willson Peale: a 30-foot-tall circular temple with 10 Corinthian columns (and spaces for the columns representing the three still-unratified states) and a roof whose cupola was crowned by the figure of Plenty, holding her cornucopia. The words In Union the Fabric Stands Firm were carved into the base.

At Union Green, James Wilson [“Flawed Founder,” May|June 2011] climbed onto the Grand Federal Edifice and delivered a speech to an audience of about 17,000 people.

“A people, free and enlightened, establishing and ratifying a system of government which they have previously considered, examined, and approved!” he told them. “This is the spectacle which we are assembled to celebrate; and it is the most dignified one that has yet appeared on our globe.”

After the address, the assembled multitudes had dinner, where they were served locally made porter, beer, and cider, and drank toasts to, well, pretty much everybody.

A year later, the newly elected President Washington sent Hopkinson a letter informing him that the Senate had confirmed his appointment as a federal judge for the US District Court for Pennsylvania. In congratulating him, Washington wrote: “I have endeavoured to bring into the offices … such Characters as will give stability and dignity to our national Government.”

In November 1790, Hopkinson was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Law degree by the penultimate incarnation of his alma mater, the University of the State of Pennsylvania. A year later it would merge with the briefly resuscitated College of Philadelphia (which had been closed during most of the Revolution for its overly Tory ways) into a single institution: the University of Pennsylvania.

On the morning of May 9, 1791, Hopkinson was “seized with an apoplectic fit,” in the words of Benjamin Rush, “which in two hours put a period to his existence, in the 53d year of his age.” He was buried in the Christ Church graveyard, not far from Franklin, who had died the previous year. Among the provisions in Hopkinson’s will was one that would free his two “Negro Slaves Dan and Violet,” though only after the death of his wife. An anonymous contemporary of Hopkinson’s wrote:

“And be this truth upon his marble writ—

He shone in virtue, science, taste, and wit.”

Over the decades, his gravestone deteriorated to the point that no one knew for certain where his remains were buried. Finally, in the 1930s, a plot believed to be Hopkinson’s was dug up. The skeletal remains were sent to Penn Anatomy Professor Oscar V. Batson, who concluded that they were indeed Hopkinson’s.

After his old bones were re-buried, a new headstone was placed over them, this time with a plaque listing his most significant accomplishments. It’s a pretty impressive list. But it doesn’t begin to tell the whole story.

SIDEBAR

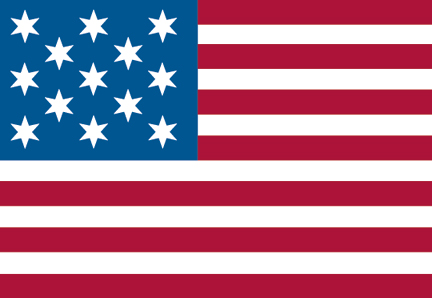

Designs for Wine and Country

On May 25, 1780, Francis Hopkinson submitted a request for payment for certain “labours of fancy” to the Continental Marine Committee and Board of Admiralty with the following comments:

It is with great pleasure that I understand that my last Device of a Seal for the Board of Admiralty has met with your Honours’ Approbation. I have with great Readiness, upon several Occasions exerted my small Abilities in this Way for the public Service; &, as I flatter myself, to the Satisfaction of those I wish’d to please, viz

The Flag of the United States of America

7 Devices for the Continental Currency

A Seal for the Board of Treasury

Ornaments, Devices & Checks for the new Bills of Exchange in Spain & Holland

A Seal for the Ship Papers of the United States

A Seal for the Board of Admiralty

The Borders, Ornaments & Checks for the new Continental Currency now in the Press,—a Work of considerable Length

A great Seal for the United States of America, with a Reverse.—

For these Services I have as yet made no Charge, nor received any Recompense. I now submit to your Honour’s Consideration, whether a Quarter Cask of the public Wine will be a proper & a reasonable Reward for these Labours of Fancy and a suitable Encouragement to future Exertions of a like Nature.

His claim to have designed the American flag—which he sometimes referred to as the “Naval flag of the United States”—isn’t doubted by those who have studied the matter. (Even the US Postal Service, which tries hard to avoid stepping into unsettled historical debates, honored Hopkinson as “Father of the Stars and Stripes” on Flag Day 20 years ago.) One of his designs placed the stars in symmetrical rows, while another had them in a circle. True, they were six-pointed stars—probably taken from the family crest he brought back from a visit to England—not the five-pointed stars that were eventually used in the flag sewn by Betsy Ross. But that’s a pretty minor adjustment.

“Of all candidates, he is the most likely designer of the stars and stripes,” says Edward W. Richardson in Standards and Colors of the American Revolution, while A History of the United States Flag, published by the Smithsonian Institution, states: “The journals of the Continental Congress clearly show that [Hopkinson] designed the flag,” adding that the authors of that volume had “no question that he designed the flag of the United States.”

And even though his enemies blocked all attempts to have him paid for his services, “they never denied that he made the designs.”

Hopkinson never did get his quarter-cask of wine, even though it seems, from this vantage point, a pretty reasonable recompense for the time and graphic-design talent required—not to mention the enduring quality of some of the designs. The Commissioners of the Chamber of Accounts concluded that the charge was “reasonable and ought to be paid.” But he ran afoul of bureaucratic nitpicking and some personal animosity from his enemies in the Board of Treasury, who said that he had neglected to submit any vouchers supporting his requests. When he resubmitted the bill, this time for money ($7,200, which sounds like a lot but wasn’t, given the weak state of the dollar), the Board of Treasury again postponed the matter, sniping that he “was not the only person consulted on these exhibitions of fancy” and thus “wasn’t entitled to the full sum charged.” When he went to its offices in person, the door was literally slammed in his face.

Congress appointed a committee to investigate the quarrel and, when the Board of Treasury refused to appear before it, issued a report that lambasted the behavior of its secretary and two commissioners as “very reprehensible, extremely disgusting, and has destroyed all friendly communication of Counsels, and harmony in the execution of Public Affairs.” It recommended the dismissal of all three men, but that too got bogged down in bureaucratic torpor. All this while a war was going on.

—S.H.

SIDEBAR

From Bluecoat to Redcoat, a Turncoat

On September 7, 1774, Jacob Duché C1757 G1760 was asked to give the opening prayer for the First Continental Congress at Carpenters Hall. Having served as professor of oratory for the past 15 years at the College of Philadelphia, where he was a trustee and a former valedictorian of his class, he knew how to move people with words. And as rector of Christ Church, the most prestigious Anglican church in Philadelphia, his words carried considerable weight.

Duché gave Congress what it wanted that day, and then some. He began by imploring the Almighty to “look down in mercy” on “these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod of the oppressor and thrown themselves on Thy gracious protection, desiring to be henceforth dependent only on Thee.” He also prayed for the Americans to “defeat the malicious designs of our cruel adversaries; convince them of the unrighteousness of their Cause and … constrain them to drop the weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle!”

The effect of his words was electric.

“I must confess I never heard a better prayer … with such fervor, such ardor, earnestness and pathos, and in a language so elegant and sublime for America [and] for the Congress,” wrote John Adams in a letter to his wife Abigail. More to the point, “I never saw a greater effect upon an audience.”

Duché was still aboard the Revolutionary bandwagon in July 1776 when the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence. He and the vestry of Christ Church passed a resolution removing all references to King George III, and five days later Congress voted to make him its first official chaplain.

A year of war apparently changed his mind. When General William Howe’s troops marched into Philadelphia on September 26, 1777, Duché prayed aloud for the king at Christ Church. He was promptly arrested and thrown into jail, though quickly released. Three weeks later he would resign as chaplain to Congress, citing the pressure of work and poor health.

But by then he had already written a letter to General George Washington that would change his reputation in the eyes of history forever. Given the incendiary contents, it’s worth quoting at some length.

After saying that “all the world” knew that Washington’s motives for serving his country were “perfectly disinterested,” Duché expressed shocked disbelief at the cause to which he had committed himself and his country: “What then can be the consequence of this rash and violent measure and degeneracy of representation, confusion of councils, blunders without number?” He pooh-poohed the Pennsylvania faction for “the weakness of their understandings, and the violence of their tempers,” and dismissed the other states’ Congressmen as a bunch of “Bankrupts, attorneys,—and men of desperate fortunes,” adding: “Long before they left Philadelphia, their dignity and consequence was gone; what must it be now since their precipitate retreat?” (His one unnamed exception was presumably his brother-in-law and former classmate, Francis Hopkinson: “a man of virtue, dragged reluctantly into their measures, and restrained, by some false ideas of honour, from retreating, after having gone too far.”)

After heaping contempt on the American military effort—“your harbours are blocked up, your cities fall one after another; fortress after fortress, battle after battle is lost … How unequal the contest! How fruitless the expence of blood?”—Duché then made his pitch: “represent to Congress the indispensible necessity of rescinding the hasty and ill-advised declaration of Independency,” and recommend “an immediate cessation of hostilities.” Then appoint some “men of clear and impartial characters, in or out of Congress … to confer with his Majesty’s commissioners” with some “some well-digested constitutional plan.” And since “millions will bless the hero that left the field of war, to decide this most important contest with the weapons of wisdom and humanity,” he added: “Oh! Sir, let no false ideas of worldly honour deter you from engaging in so glorious a task …”

Finally, if Washington couldn’t persuade Congress to negotiate a surrender, Duché suggested that he still had “an infallible recourse” at his disposal: “negociate for your country at the head of your army.” In other words, sell out your country in secret and save your own hide.

Washington promptly turned the letter over to Congress. He then wrote a letter to Hopkinson, who was serving the patriot cause in a number of capacities. (See main story.) Had “any accident have happened to the army entrusted to my command, and had it ever afterwards have appeared that such a letter had been … received by me,” Washington explained, “might it not have been said that I had, in consequence of it, betrayed my country?”

Washington was clearly appalled at having received “so extraordinary a letter” from Duché, “of whom I had entertained the most favorable opinion, and I am still willing to suppose, that it was rather dictated by his fears than by his real sentiments.” But, he told Hopkinson, “I very much doubt whether the great numbers of respectable characters, in the state and army, on whom he has bestowed the most unprovoked and unmerited abuse, will ever … forgive the man, who has artfully endeavored to engage me to sacrifice them to purchase my own safety.”

If Washington was appalled, Hopkinson was apoplectic.

“Words cannot express the Grief and Consternation that wounded my Soul at the Sight of this fatal Performance,” he wrote to Duché. “What Infatuation could influence you to offer to his Excellency an Address fill’d with gross Misrepresentations, illiberal Abuse and sentiments unworthy of a Man of Character? … I could go thro’ this extraordinary letter, and point out to you the Truth distorted in every leading part. But the World will doubtless do this with a Severity that must be Daggers to the Sensibilities of your Heart.”

Apart from the moral failure, Hopkinson warned: “You will find that you have drawn upon you the Resentment of Congress, the resentment of the Army, the resentment of many worthy and noble characters in England whom you know not, and the resentment of your insulted Country …

“You presumptuously advise our worthy General, on whom Millions depend with implicit Confidence, to abandon their dearest Hopes, and with or without the Consent of his Constituents to negotiate for America at the head of his Army. Would not the Blood of the Slain in Battle rise against such Perfidy? …

“I am perfectly disposed to attribute this unfortunate step to the Timidity of your Temper, the weakness of your Nerves, and the undue Influence of those about you,” Hopkinson told his old friend and brother-in-law. “But will the World hold you so excused? Will the Individuals whom you so freely censured and characterized with Contempt have this tenderness for you? I fear not … I pray God to inspire you with some Means of extricating yourself from this embarrassing Difficulty.”

For his own part, Hopkinson said, “I have well considered the Principles on which I took part with my Country and am determined to abide by them to the last Extremity.” Asking Duché to send his love to his mother and sisters in Philadelphia, he concluded: “May God preserve them and you in this Time of Trial.”

Duché fled to England the following year, and when the American army re-entered Philadelphia, his property was confiscated. Hopkinson interceded on behalf of his sister and her children to recoup enough money to pay their passage to London.

The two classmates never saw each other again.

—S.H.