The last of Penn football’s “Mungermen” recall the painful transition from big-time football to the Ivy League 70 years ago—including a University president’s short-lived “Victory with Honor” campaign, a not-so-harmonious “harmony dinner,” and the unceremonious exits of a legendary football coach and controversial athletic director.

By Dan Rottenberg

Through the first half of the 20th century, the University of Pennsylvania was celebrated in many quarters not as America’s first university, nor for incubating America’s first medical school, first business school, first psychological clinic, and the world’s first electronic computer—but for its leading role in the American game of football.

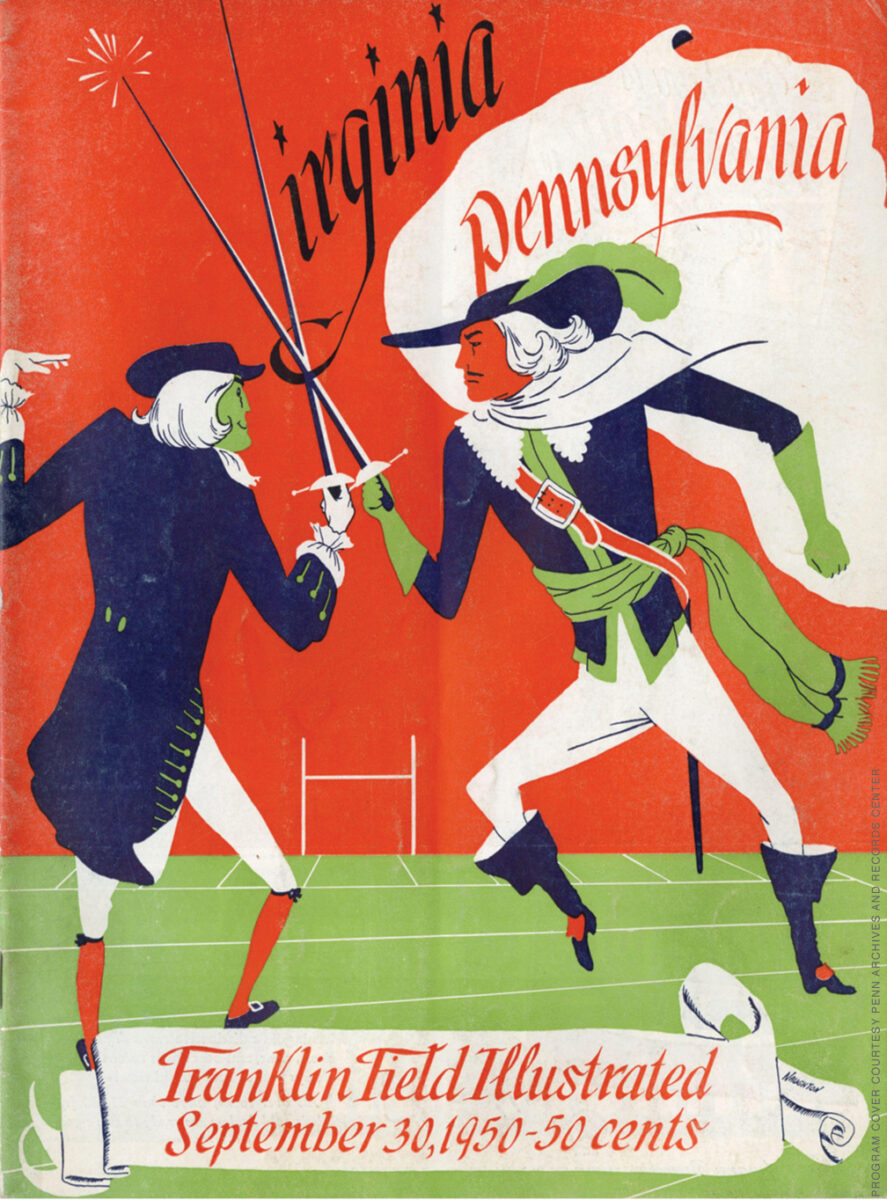

From the sport’s earliest years in the 1870s, Penn became football’s primary laboratory for innovation, from the first fake handoff to the first placekick to the flying wedge to the “quarterback kick” (a forerunner of the forward pass) to America’s first football stadium, not to mention America’s first double-decked stadium. College football’s two most prestigious awards—the Heisman Trophy for the game’s outstanding player, and the Outland Trophy for the best lineman—are both named for Penn men. The Quakers won seven national championships in the 1890s and 1900s, played in the Rose Bowl in 1917, and competed against national powers in the 1920s. Through most of the 1940s, Penn football teams led the nation in home attendance, routinely drawing crowds of 70,000 and more to Franklin Field at a time when the local professional team, the Philadelphia Eagles, rarely attracted more than 12,000. Even now, Penn retains its status as the institution that has played more football games than any other organized team at any level—professional, collegiate, or scholastic.

Yet midway through the 20th century, this same gridiron colossus stunned the sports world by voluntarily downgrading its big-time football program to join the newly organized Ivy League, a consortium of eight of America’s oldest and most distinguished universities. This earth-shaking decision sought to make Penn as famous academically as it had been athletically. But the newly established Ivy code required all eight schools to subordinate athletics to academics, which in practice meant eliminating athletic scholarships, spring football practice, the physical education major, and any form of special privileges for athletes. Under the Ivy code, intercollegiate athletics would be operated not as vicarious entertainment for alumni or as a promotional fundraising tool, but as an educational opportunity for all students, much like any other campus activity.

These conditions imposed little sacrifice on the other Ivy League schools, which already subscribed to most of these ideals. But it seemed a cruel wrench for Penn, whose teams had twice been ranked among the nation’s top ten in the 1940s and had routinely thrashed their Ivy rivals during that decade. Harvard and Yale had even refused to play Penn after 1943 and objected to admitting Penn to the newly organized league altogether.

Yet ironically, Penn had honored much the same academic standards long before the Ivy code was formalized. As early as 1917, Penn had transferred control of its athletics programs from its alumni to the University administration (in theory, if not necessarily in practice). In 1931, when Penn was one of only four American universities taking in more than $1 million annually in football ticket receipts, the University assumed full control of all athletics—sharply reducing Penn’s football budget, de-emphasizing intercollegiate competition in favor of intramural sports, and classifying coaches as full-time faculty members.

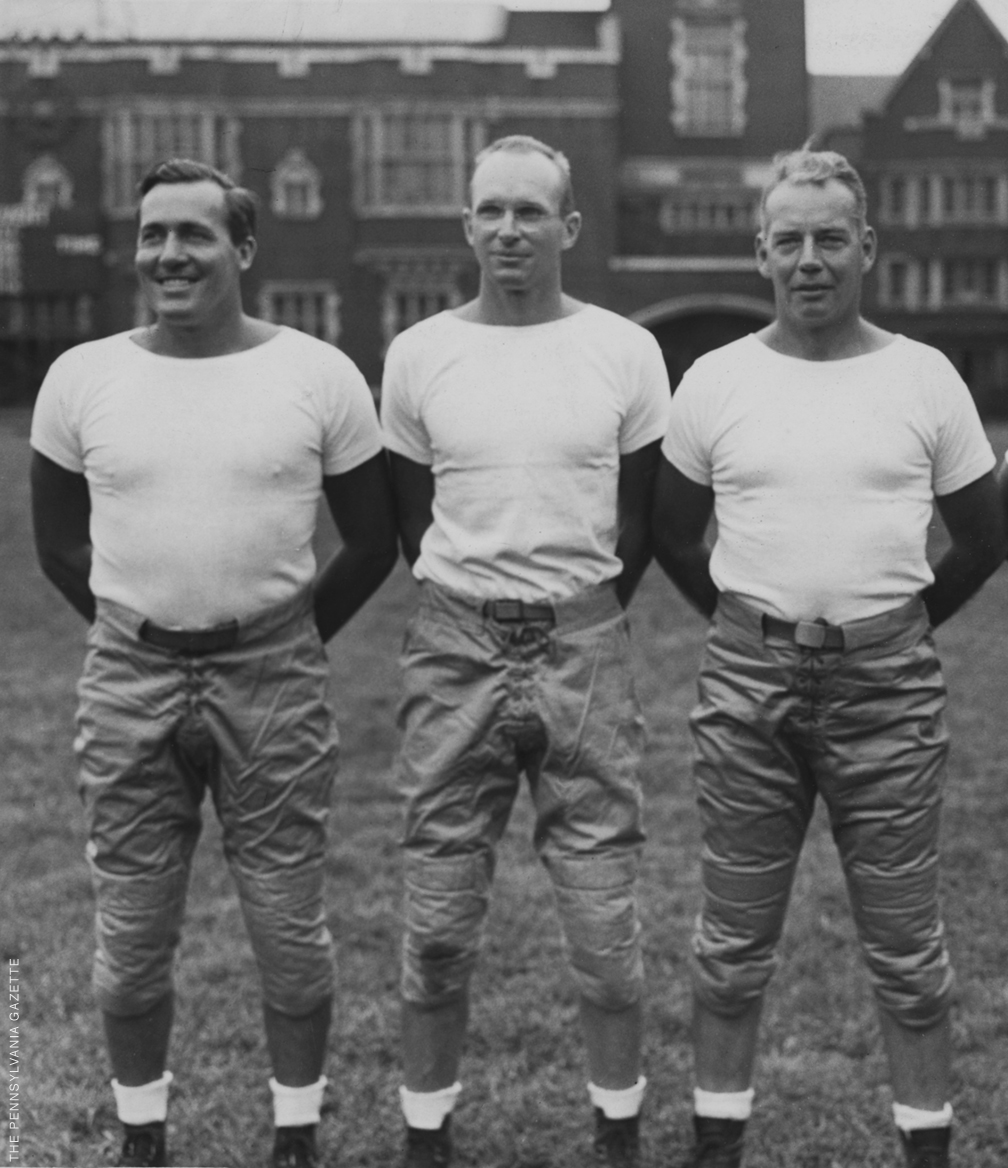

Despite these handicaps, by the 1940s Penn was once again ranked among the nation’s football powers, thanks largely to its fortuitous choice of a remarkable head coach. George Munger Ed’33 was a quiet introvert, just 29 years of age, when Penn selected him over a host of more celebrated candidates in 1938. As a student and teacher at Episcopal Academy on Philadelphia’s Main Line, Munger had been marinated in the concept of a coach as a teacher and adviser rather than a drill sergeant, and consequently he personally embodied the Ivy philosophy long before the Ivy League was formalized.

In pursuit of his vision, Munger encouraged his players to call him “George” instead of “Coach.” He let the team captains pick the starting lineup each week and call the plays, with only minimal direction from the sidelines. After practice, he left his players free to run their own lives. He was a poor speechmaker who shrank from giving pep talks or posting slogans in the locker room. As a football tactician, he was merely average. He was, wrote Collier’s Weekly, “shy, inarticulate, slightly-goofy-looking.” Yet by devoting himself to his players and treating them as adults, Munger generated a loyalty and commitment from them that few other coaches enjoyed anywhere.

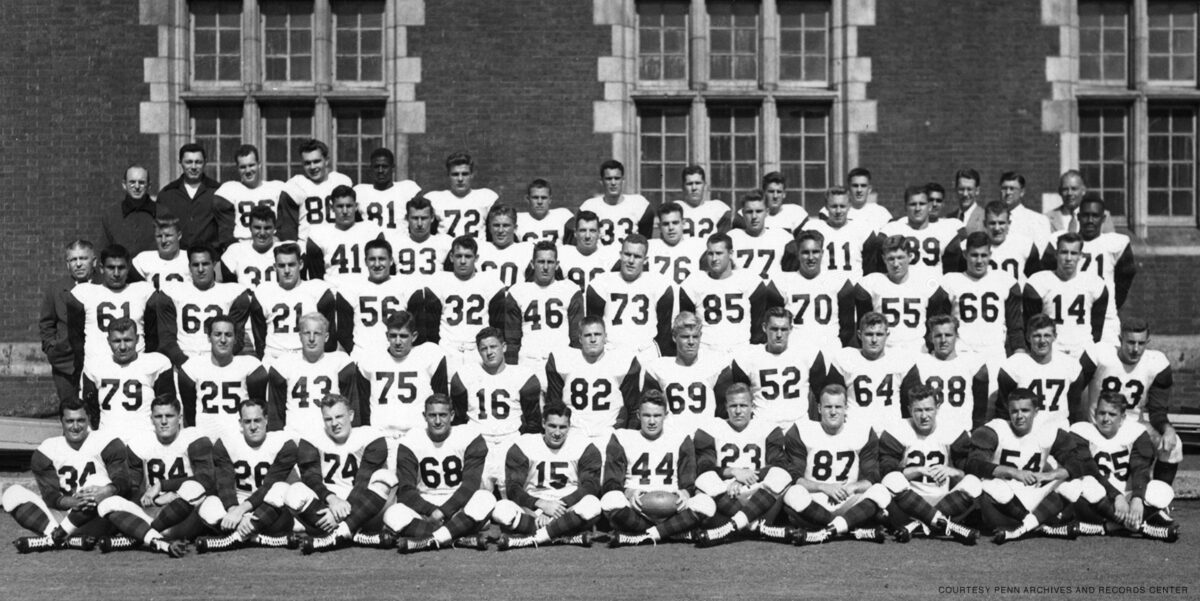

During Munger’s 16 years at Penn—then the longest tenure in the school’s history—Penn teams lost just six of their 62 games against Ivy League opponents. The Quakers beat Army four times, once by a score of 48–0, and Navy nine times. They administered sound thrashings to famous teams like Wisconsin and North Carolina, and they were led by stars like Chuck Bednarik Ed’49, widely considered the greatest college center of all time.

Since Penn seemed so far superior in football to its Ivy League rivals, those schools generally assumed that Penn must be inferior academically or ethically, if not both. Penn was ridiculed for offering a major in physical education, a presumed haven for football players who couldn’t cope with standard academic courses. Penn was also seen as benefitting from Pennsylvania’s State Senate scholarship program, which entitled each of the commonwealth’s 50 state senators to award three state-supported scholarships to Penn each year. Yet while Penn did have more players on scholarship than other Ivy programs in the 1940s, they ranked relatively high academically.

Penn’s hopes of joining the Ivy League were further complicated by the arrival in 1948 of a new president in Harold Stassen Hon’48, the former governor of Minnesota, who was hired primarily to address the University’s financial deficit. Stassen’s desire to join the Ivy League was exceeded only by his pressing need to exploit Penn’s famous football team to help solve the University’s fiscal quandary. Thus, even as Stassen met with other Ivy presidents to discuss ways to de-emphasize football, he was arranging a big-time football schedule as a tool for increasing Penn’s national visibility and for generating greater ticket sales and national television exposure—the very opposite of the de-emphasis that the other Ivy presidents had in mind.

Although the restrictions agreed upon by the Ivy presidents went into effect in 1953, the round-robin Ivy League schedule didn’t begin until 1956. And the new big-time schedule created by Stassen and his athletic director Fran Murray C’37 began in 1953. Stassen, a Republican politician who sought the US presidential nomination in 1948 and 1952, departed early in 1953 to take a government job, leaving Munger and his players to face one of the most formidable schedules in college football history while hampered by the newly approved Ivy League restrictions against athletic scholarships and spring practice. In effect, in 1953 they were required to play by Ivy League rules even though they played only one Ivy League opponent—Penn’s traditional rival, Cornell.

Murray was fired as athletic director that May, and a week later Munger (who was only 44 years old) and his staff resigned in protest rather than commit professional suicide that fall. Penn’s acting president, William DuBarry C1916, prevailed on them to remain for one more season, but their hearts were no longer in the task, and the recruiting they did for their successors was minimal.

Meanwhile, Penn players who were recruited to play big-time football found themselves competing against a big-time schedule but with the handicap of Ivy League restrictions. In many cases, they also found themselves unqualified academically for an Ivy League curriculum but were precluded, under Ivy restrictions, from receiving the sort of tutoring that had previously been provided to Penn players who needed it. Against the so-called “suicide schedule” of the next three years, Penn won just three games in 1953 and none in 1954 and 1955.

This bizarre football saga has been the subject of many newspaper and magazine articles and several doctoral theses. But these accounts have often overlooked the personal stories of those players and coaches who were caught in the gears of Penn’s painful transition to the Ivy League. The excerpts below convey the words of several “Mungermen,” as Munger’s players were known. Some of them have died since 2019, when I began interviewing about two dozen survivors of the Munger era. Their voices provide a sense of the human price that was paid for the prestige of Ivy League affiliation, and of the confusion and bitterness that resulted from Penn’s decision to scrap its celebrated football program. But with 70 years of hindsight, all of them concede that, in retrospect, Penn did the right thing, as the University’s affiliation with the Ivy League became the decisive factor in its ability to attract world-class faculty and world-class students.

Missing, of course, are the voices of the involved coaches and administrators, who were already adults in the early ’50s and thus long gone by the time I undertook this project. Readers may rightly reproach me for failing to undertake this mission decades ago. I trust they will agree when I reply: Better late than never.

Ernest “Ernie” Prudente Ed’51 GEd’62

He played tackle for Penn’s 1948, 1949, and 1950 teams, and went on to become a coach at Haverford and Swarthmore. Interviewed January 11, 2019. Died April 14, 2020.

When I was a sophomore, I was on the third team and hardly ever played. In those days, they didn’t have many subs. Even if you were on the second team, you might not get in the game. When you played, you ran down on kick receiving teams, punting teams, kickoffs—you played the whole game.

So, guys were killing each other in practice because everybody wanted to play on Franklin Field. That was everybody’s goal—heaven on earth and everything else. It’s hard to believe, 80,000 people in the stands, screaming. Just a wonderful experience.

George Munger was like a father image. He always took care of his boys. He wanted everybody to love Penn like he did. These poor guys came to Penn with no coats; he bought them suits, shirts, ties. He wanted everybody to look Ivy League and be classy looking. He wanted good morals, good everything.

Every time we won a game, we got an ice cream cake the following Tuesday night. My junior year, we lost to Army, 14–13. [Army was ranked No. 2 in the nation at the time.] But we got an ice cream cake anyway.

A guy like me, I wasn’t like an All-American, and I was an education major. After my senior season, George called me into the office and said, “What are you gonna do now?”

I said, “Well, my education takes five years to get a master’s degree.”

He said, “We’ll take care of that for you, too.”

So I had a scholarship for my fifth year even though I was not playing. Who would ever do something like that? It made me cry.

When I came to Penn, Harold Stassen got to be president. He came to Hershey to see us practice. He said we’re gonna win with glory and all that other stuff. [Author’s note: Stassen’s slogan, announced by his athletic director Franny Murray in 1950, was “Victory with Honor.”]

I got out in ’51. And George had a hard time winning games after that. When he quit, in ’53, he was only 44 years old—to become director of intramural athletics. His assistant coach Paul Riblett W’32 said, “The only thing George does now is check the pH level in the water at the swimming pool.” I know he did more than that.

Norman Wilde W’53

He played end on Penn’s 1950, 1951, and 1952 teams and later ran an investment house in Philadelphia. Interviewed February 6, 2019.

We played nine games in those days, and seven or eight of them were at home. We used to take a 45-minute bus ride to Philmont Country Club the day before home games, change up there, and have a workout on one of the fairways on the south golf course. Then we would go in and have dinner. We’d sleep there. They had some single rooms upstairs for the best players, and a big room where they put cots in for the rest of us. And you’d get up in the morning and have a big glass of orange juice and a huge filet mignon and a big potato—stuff like that. We’d eat that at about 10 in the morning before riding back to Philly.

At that time, we brought in the first two Black players to play for Penn, Bob Evans C’53 and Eddie Bell C’54. Evans was the captain of the 1952 team. Eddie Bell was a first team All-American that year. After dinner up in Hershey one year, four or five of us decided to go out and get some ice cream cones. We drove over to Hummelstown, which is between Hershey and Harrisburg. We walked into this ice cream store, and Bell was with us—four white guys and one Black guy. And the owner or the counterman said, “We can’t serve him.” So we all walked out: “If you’re not serving Eddie, you’re not serving us.”

George Munger had a contract that went through the ’53 season. As I remember assistant coach and former Penn football player Bill Talarico Ed’49 telling the story, George had the chance to continue as coach, or become head of intramural athletics at Penn. He was trying to make up his mind because they were about to enter the Ivy League. And he knew that he wasn’t going to get the same things scholarship-wise, compared to what he had been getting. There was a Penn trustee—Jim Skinner C1911, the president of Philco—who gave a lot of money to the University. [Author’s note: A major booster, Skinner was the donor of “Skinner Scholarships” for Penn football players and paid for the program’s preseason camp in Hershey.] According to Talarico, any time Munger had a problem getting a good football player in through the admissions department, Skinner would go to the dean. Talarico said that he was on his way back to a meeting with Munger and line coach Rae Crowther and Riblett to decide what they wanted to do the following year. “I walked in the room,” Talarico said, “and somebody told me that Skinner just had a heart attack and died.” And that’s why George picked up the intramural stuff.

I had dinner with [former Penn State football coach] Joe Paterno about 20 years ago at some charity function. And he said, “When Penn went Ivy League, that made the program of Penn State, because we used to lose six to eight recruits a year to Penn. I know George was grief stricken over that, but we were the ones who took advantage of that situation.”

Richard “Dick” Rosenbleeth W’54 L’57

He played defensive end on Munger’s last teams, from 1951 to 1953. He became a lawyer and a coach in Philadelphia, beginning as an assistant under Munger’s successor, Steve Sebo. Interviewed March 8, 2019.

We had the biggest scholarship class in the history of Penn football at that time. There were, I think, 33 football scholarships, because the Stassen “Victory with Honor” program had just begun. We had major opponents from around the country. So, it was a very interesting time, and we had a great freshman team with guys like Joe Varaitis W’54 and Jack Shanafelt W’54, who became stars. We beat everybody by four and five touchdowns. Look magazine called us “Stassen’s Assassins.” That’s where that expression originated.

George Munger was really a gracious man, a gentleman, not a typical football coach in his outlook and the way he handled people. He was interested in the whole picture of college football, not just the wins and losses. Of course, he was very competitive. But he loved the game and the color and excitement. And he loved to see the progress of his players over the years, both as players and as citizens.

I didn’t start my sophomore year [1951]. I was on the kickoff team, and I played in most of the games. And then my junior year, I started on defense. They were great, exciting years—Franklin Field filled, playing the best teams, the best coaches, the best players in the country.

The game tickets were a major factor for the players. You got four free and you could buy eight. And there were times—a couple of the Notre Dame games, maybe Ohio State—where players would buy the eight tickets and then sell them. And that was important money. You could make two or three hundred dollars on a game. This was at a time when tuition was only about $600 a year. And we played just about all our games at home.

In ’53 we played under both the new Ivy League restrictions and the new NCAA substitution rules. That was a disaster. No spring practice, and you had to play both ways. You couldn’t stay in the game—they had some silly rule that if you were in on defense, you had to stay in for at least ten plays. Also, it limited the number of our recruits.

As I understand it, the other Ivy presidents were going to boot Penn out of the Ivy League. They weren’t going to play Penn anymore, if Penn continued on the Stassen path, with the big-time schedule and big-time crowds, and getting your revenue from that.

By 1953, out of the 33 very good scholarship football players we had as freshmen, there may have been 12 or 13 left. They either left school or were injured or were no longer interested in playing football. And the sophomore and junior classes were much more limited.

Oh, there were some good football players, but not the quantity you need if people get injured and you need replacements. But ’53 was still a great year because of the opponents and playing on Franklin Field. The games we did win—Eddie Gramigna W’54 kicked a field goal to beat Navy, 9–6, and we beat Vanderbilt and Penn State. But playing that national schedule under the new Ivy League rules brought George his first losing season.

I always took the position that to have dropped the major college football teams from Penn’s schedules was a big mistake. But I’ve since concluded, if you look at what the University has become, and its affiliation with the rest of the Ivies, it was probably the right course. Still, if you ask any of the Mungermen, we would have still opted for seventy, eighty thousand people in Franklin Field playing Army, Navy, Notre Dame, and so on.

The last time I saw George Munger was the last Mungermen get-together before he died [in 1994]. He had made a speech, and it was a typical George Munger speech—funny, witty, and inspiring. I went to the game afterward, and I was sitting behind George, and I said, “George, what a great speech. Just like old times.” He looked at me and his eyes filled up with tears—I could see them behind his glasses—and he hugged me and said, “Richard, I love you.”

George Bosseler W’54

An All-American defensive back in 1952 and captain in 1953, he wrote a letter to Penn officials pleading for the right to hold spring practice in preparation for Penn’s 1953 season. Interviewed September 13, 2019. Died April 21, 2021.

George Munger was a shy person and a humble person. He didn’t go out of his way to embellish anything. If he gave an interview, it was pretty short. He had a lot of empathy, and he cared for people. He would often ask—not only me, but all the players—“How are you doing in school? Do you need any help with it?” I don’t know anybody that disliked him except, you know, Fran Murray at the end.

Early in 1953, the NCAA changed the rules from the two-platoon system to one-platoon, which required the coaching staff to utilize players differently. And they imposed some other substitution rules too. If you came out of the game in the first quarter, you couldn’t go back in until the second quarter. Meanwhile, the Ivy League had agreed to eliminate spring practice. But they were mostly playing each other. We had a big-time schedule with only one Ivy opponent.

When this happened, we players didn’t know how to handle it. So, I called a meeting in late February of ’53. And through the consensus of the team, I wrote a letter to the University’s trustees. It gave some examples of perhaps what we could do to keep ourselves in shape and maintain unity in the absence of spring practice.

One suggestion was touch football. Another one was track. Another was rugby. DuBarry [Penn’s acting president] replied in a letter to me, saying he agreed with everything that I had written, except that he didn’t know how the University and/or the Ivies would accept a special sport just for the football team, unless it was open to all students.

So that didn’t come to pass. Some of the guys—not all—played different sports or intramurals in the spring. I played baseball, but only that one year.

In any case, my letter to the Penn trustees leaked to the Daily Pennsylvanian and other news outlets. DuBarry summoned me to his office. I don’t even know if I knew he was the president before I got the message to report to his office. He wasn’t a name you would see in news articles, like Harold Stassen. I put on the best clothes I had and reported to College Hall. The secretary led me into a big room—nice furniture, long table, maybe six chairs on each side. DuBarry sat at the head. I think I sat between George Munger and DuBarry. Fran [Murray] was on the other side of the table.

And this was how it started: Mr. DuBarry said, “Mr. Bosseler. Why did you write this letter?” And I thought to myself, Oh, shit.

I went through the litany of telling him why. But that’s putting a 21-year-old kid on the defensive in a hurry, right? Then he tried to lead the discussion between Fran and George. From the questions that he was asking, I got the feeling that he didn’t know much about athletics. And of course, Fran and George each had their own agenda, their own job description. Fran’s job description, through Stassen, was to fill Franklin Field. But the part that I didn’t know at the time was that the University was in financial difficulties and Stassen had felt filling Franklin Field was a way of gaining revenue.

What he didn’t do was consult with George. And George took offense at this, because George was the guy who had to play these teams. And now he had to play these teams without spring training, and with a change in rules, which meant a change in coaching philosophy—how to use players effectively. And George resented it all.

So the two of them [Munger and Murray] went back and forth. And then Fran turned to me and said, “You guys are afraid to play this schedule, aren’t you?”

“No, we’re not,” I said. “We just would like to have some good backup, so mentally and physically, and in every other way, we’re prepared to play these teams.”

Well, to Fran, it looked like we were scared. That wasn’t true. We had good ballplayers out there. Many guys could have played for any one of those teams we played. George stood up for us, too. “These guys are good football players,” he said. “They can take care of themselves.”

That was kind of how the conversation went. I don’t think there were any winners or losers. Five days after the meeting [on March 9, 1953] there was a so-called “harmony dinner” for the team, summoned by Murray, at a downtown club. I remember Fran saying at the dinner that we players were afraid of our 1953 schedule, and George took the players’ side. [Author’s note: Several former athletes recalled an uncomfortable and tense meeting, with Munger calling Murray’s prepared remarks an unjust attack on his players. Rosenbleeth said he fruitlessly pleaded for spring practice by asking, “Would you exclude us from studying before finals?” Former player John Cannon W’54 called it “a nasty exchange—an unusual experience, to say the least, for students to watch that fight going on between adults.”] Fran was pretty slick, in the sense that he was good with words. He had a way of putting the knife in you, too.

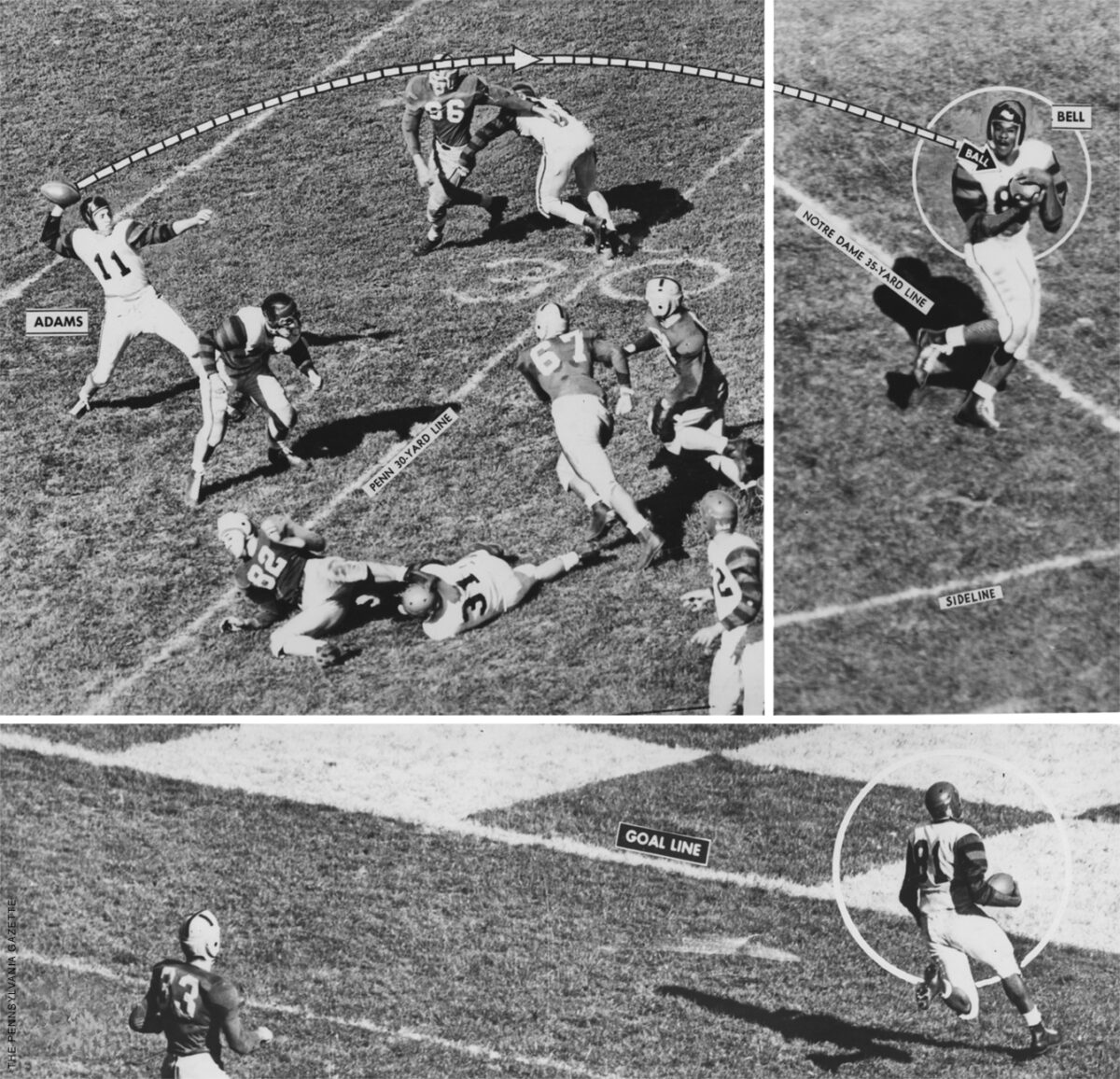

If you look at the scores of our games in ’53, we were only blown out by California. Otherwise, we were competitive. We lost to Ohio State, 12–6. Michigan, 24–14. Notre Dame, 28–20. But looking back, we certainly lacked the manpower these teams had. And they were all good athletes, obviously. By comparison, we had maybe 30 guys who played a reasonable amount of time. We doubled up so much—I was on all the special teams. And back then, the game was a little bit different: less passing and more hard-nosed stuff.

Jim Shada W’56 GEd’67

As a Penn sophomore in 1953, he played on Munger’s last team and captained the 1955 team, which lost all nine of its games. He went on to work at Penn for more than 30 years. Interviewed February 12, 2019. Died June 6, 2019.

When I was recruited [in 1952], the Ivy League didn’t exist. And if you would have said to me when I was recruited, you’re going to play some Ivy League schools, I would have said, “Where’s the Ivy League?” I went to Penn to play against the best teams in the East and South and Midwest. We played California, Michigan, Ohio State, Virginia Tech. We played Notre Dame, and Army and Navy, who then were big powerhouses.

When Jerry Ford C’32 G’42 came to campus [as athletic director in 1953], I was working as a clerk in the dorms and helped him get settled. He certainly believed in the Ivy leaguetotally. He came from St. George’s School in Rhode Island, which is a good prep school. And he was an academic.

The other Ivy League schools had thin skins, because we were beating the hell out of them over the years. And they did everything they could, I think, to make it difficult for us [to join the Ivy League]. Whoever struck the deal to “allow” us into the Ivy League didn’t compensate for the fact that we’d have a transition period. My class was George Munger’s last recruiting class. We didn’t have a team squad meeting that I know of where Munger came and explained what was going on. And we suffered from the restrictions: no spring practice, difficulty in the classroom, and no help in the classroom.

We played under these Ivy rules—but we didn’t know what the Ivy League was! We never had an Ivy League schedule. I’ll give you a laughable example. My senior year [1955], I was named an All-Ivy guard. In my four years at Penn, I played four games against Cornell, two games against Princeton, and that was it. I never saw Brown, Dartmouth, Harvard, or Yale. And I was All-Ivy. Bob Paul W’39 [Penn’s director of sports information] pulled it off. He said Penn had to have somebody, and I was the somebody.

George Munger was a happy-go-lucky guy. Bill Talarico, the backfield coach, was tough as nails. Rae Crowther was probably the best line coach in America, and also the inventor of the blocking sled. Crowther taught me how to play football—what to do with your feet, what to do with your balance, what to do with your mind. But I never learned one bit of football after that year. Never. Because Crowther left. Munger left. They all left.

My junior and senior years, we went 0 and 18. We didn’t win a game.It was brutal. When we stayed at the country club the night before games, I used to room with Stan Chaplin W’56, and we would talk about what was coming. I’ll never forget some of those conversations. We’d say, “Well, let’s see. We have Penn State, Navy, Notre Dame, and Army coming up in the next four weeks. Lord above, send down a dove.” It’s an old saying my Irish grandmother used. That summed up how we felt. We were desperate.

What’s interesting is, in those games, we played pretty good in the first half. But we ran out of gas in the second half. We had a pretty good first team but we had no depth. The first half against Notre Dame in ’55, we were tied. [The game began with a famous 108-yard kickoff return for a touchdown by Frank Riepl W’58.] It shocked the country when they first broadcast the score. It was nationally televised—10 of our games were, over those two years. At halftime in the dressing room, I think we knew what was coming. In the second half, Notre Dame’s third team came on and beat us. I mean, they had so much depth. They had guys playing that could have gone any place else and started.

When I think back, my Penn football career was dismal, but my academic career was very fruitful. If I was a senior in high school again, I would not have gone to Penn. To go 0 and 18? I would have gone somewhere else. But I’m glad I didn’t, because of Penn’s rigorous education. That was very, very important to me—my education there.

Epilogue

A few months after Shada and his class graduated, Penn began its official round-robin Ivy League schedule. The Quakers snapped a 23-game and nearly three-year winless streak with a 14–7 home win over Dartmouth in the second game of the 1956 campaign. According to the New York Times recap of the game, “some over-exuberant Penn rooters rushed out onto the field and tore down the goal posts. That happened with a half-minute of play remaining, and the game was concluded with no uprights.”

Three years later, Penn captured its first of 18 Ivy League football championships. Fans tore down the goal posts after every win of that 1959 season.

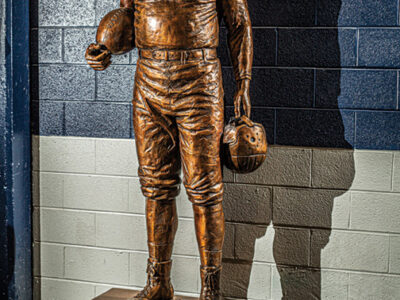

For many decades, the Mungermen gathered for reunions to relive Penn’s football glory days [“Gazetteer,” Jan|Feb 2018]. They facilitated the erection of a George Munger statue, ensuring that it can be seen by fans outdoors at Franklin Field. Many died believing that Munger’s finest coaching job came amidst all the turmoil in 1953—his only losing season.

Excerpted from The Price We Paid: An Oral History of Penn’s Struggle to Join the Ivy League, 1950–55. Copyright © 2024 by Dan Rottenberg C’64. Edited for length and reprinted with the author’s permission. Rottenberg will speak about this book on November 14 at 5:30 p.m. at the Penn Bookstore and on November 16 at 11 a.m. at the Penn Alumni Old Guard brunch at Houston Hall’s Hall of Flags. A former Penn football player and longtime journalist, Rottenberg has written 13 books, including a recent memoir, The Education of a Journalist, which was featured in the Gazette [“Professional Contrarian,” Sep|Oct 2022].