A longtime journalist’s new memoir recounts an “alternative” journey through the ever-changing print media landscape.

By Dave Zeitlin

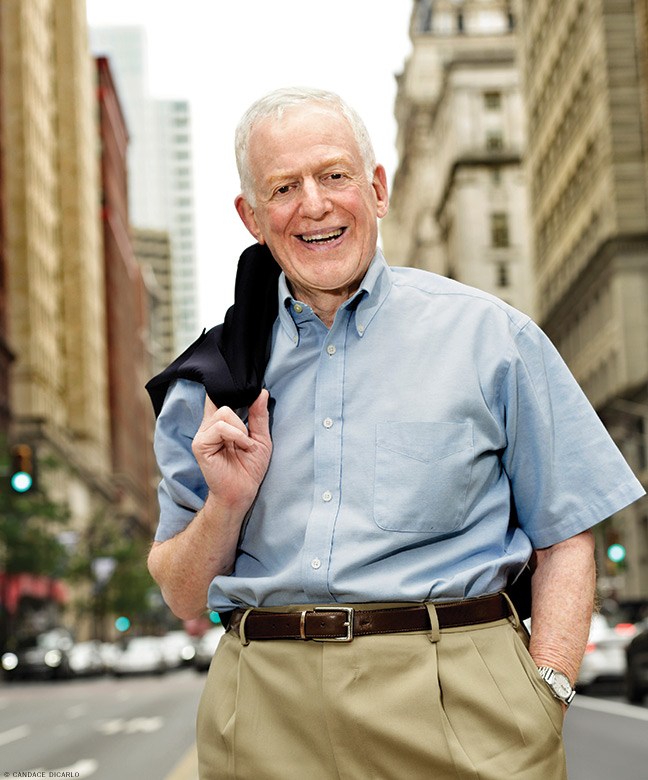

Photograph by Candace diCarlo

Excerpt | “Whatever It Takes, Let’s Do It”

On the same day he picked up his Penn diploma, Dan Rottenberg C’64 kissed his new wife Barbara Rubin Rottenberg CW’64 goodbye, hopped in his used 1957 Chevrolet, and started driving west, ready to begin a career in journalism … somewhere.

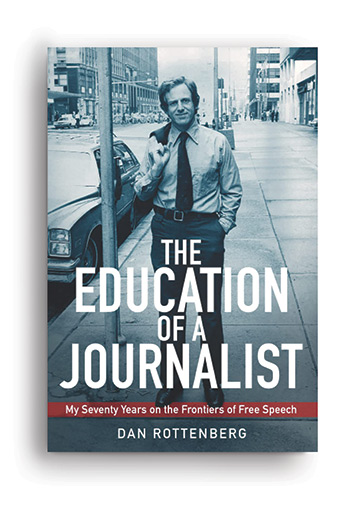

His first stop was for a job interview at the Akron Beacon Journal, a respectable newspaper in a mid-sized Ohio city that would have been a solid launching point for any fresh college graduate. The next was at the Commercial Review in Portland, Indiana—a far smaller paper in “a rural county-seat town of barely 7,000 souls,” Rottenberg writes in his memoir The Education of a Journalist: My Seventy Years on the Frontiers of Free Speech, released in February (Redmount Press).

Yet despite his initial impression of Portland as an “infinitely depressing” and “decaying community,” he was won over by an ambitious publisher and surprised himself by choosing to work at the Commercial Review, where he got to do a little bit of everything, including carving out a role as the town’s “contrarian gadfly.”

“As a Jewish urban Eastern liberal in a predominantly conservative and Christian rural Midwest county,” writes Rottenberg, who grew up in New York, “I was of course ideally suited to play the role of communal devil’s advocate.”

In many ways, getting the occasional rise out of his readers and making unconventional and often risky career choices came to define Rottenberg’s seven decades in journalism—which he chronicles in his 12th and most personal book to date. And despite his staying power in an ever-changing business, he never did remain in one job for too long, starting with his decision to leave Portland after a few years even though he and his wife had come to genuinely enjoy small-town life there in the ’60s.

“What I like are new experiences,” Rottenberg says from his Center City Philadelphia office, where at 80 he’s still cranking away on new books and articles. “To me, that was like an adventure. It was such an exotic thing to go from New York and Philadelphia to this town of 7,000 in Indiana. But after about four years, I found things were sort of repeating. And I was looking for new experiences—not familiar experiences.”

From there, Rottenberg wrote for major newspapers like the Wall Street Journal and the Philadelphia Inquirer; dove deep on features for magazines including Philadelphia and Town & Country; authored books on subjects ranging from Jewish genealogy to Penn football to Western gunslinger Jack Slade [“Profiles,” Sep|Oct 2010]; became a film and a dining critic; and, perhaps most notably, emerged as something of a pioneer of alternative media, best known as the editor of the Welcomat (which was later renamed Philadelphia Weekly).

Noting that self-reinvention is a family “tradition,” Rottenberg decided time and again to trade in the luxury of security for the thrill of adventure. “Every dozen years or so,” he says, “you want to kick over the traces of your secure existence and start over from scratch.”

Although he never could precisely predict exactly where journalism might take him, likening a career in the field to “rafting along a fast-moving river” in his memoir, Rottenberg knew from a young age that he wanted to write for a living. As a seventh grader at the Fieldston School in the Bronx, he created a newspaper, the Crusader, which “provided me and other classmates with a legitimate … outlet for our natural adolescent rebelliousness” and “reinforced my perception of journalism’s value as a tool for creating a sense of community.” Later, he phoned in sports results to New York’s then-seven daily newspapers—a foray into sports writing that continued at Penn, where he penned a column for the Daily Pennsylvanian while playing for the football team (an athletic experience he credits for teaching him how to give and take criticism). “I knew I was not going to spend my life as a sportswriter, but I did see that being a sportswriter was an opportunity for me to have much greater freedom than if I wanted to be a general writer, both at the DP and my first job out of college,” he says.

Rottenberg “assumed when I was at Penn that I would spend my whole life working on daily newspapers.” Not exactly. From Portland, he moved to Chicago, where he had landed what seemed like an ideal gig at the Wall Street Journal’s Midwest bureau. But despite the opportunities there—which included covering the famed Chicago Seven trial of 1969—he felt oddly trapped. “I thought the paper was perfect,” he says. “I didn’t feel like I could really make a difference there. I guess that’s been an important element to a lot of my career.”

Meanwhile, the Chicago Journalism Review—which had been founded as an “angry vehicle for angry journalists” who wanted to challenge the establishment press in the wake of the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests in Chicago—needed help to stay afloat. So the father of two young daughters, armed with “no assets other than my conviction that the Journalism Review was an idea worth saving,” left the WSJ to serve as CJR’s managing editor part time while freelancing on the side. “Quitting a prestigious daily newspaper with more than 1 million circulation for an upstart monthly with fewer than 10,000 subscribers seemed like a self-destructive career move,” he writes. It turned out to the be the opposite. Freelance writing would rescue the Rottenbergs when their “family fortunes hit rock bottom” at the end of 1970. And, perhaps more importantly, he’d taken his first step into the nascent realm of alternative media.

In 1972 he and his family moved from Chicago to Philadelphia, where his daughters could be closer to their grandparents and he had landed a job as an editor at Philadelphia magazine. “Even though it is time for me to return to the land of my forefathers and earn a decent living again,” he wrote in his CJR farewell column, “I suspect that in twenty or thirty years those of us who have worked on this little publication may look back and say that starting CJR was the most important thing we ever did.” He still feels that way because, despite its short-lived press run, CJR “helped plant the seeds of entrepreneurship in a generation of idealistic journalists that manifested itself from the ’70s onward in waves of alternative papers across the country, some of which outlasted the local dailies,” he writes. And it wouldn’t be long until he again “left a seemingly secure and prestigious position to go off on my own,” this time departing Philadelphia magazine in 1975 to become a full-time freelance writer and author—where his gigs included a syndicated film column for Chicago magazine, restaurant reviews for the Jewish Exponent (no pork dishes allowed), business writing for Town & Country and Forbes, op-eds for the Philadelphia Inquirer, and continued feature work for Philly Mag, including an in-depth profile of real estate tycoon Albert Greenfield that he would later turn into a book.

It also wouldn’t be long until he’d become enticed by another “alternative” outlet.

“One of the great things about being a journalist,” Rottenberg says, “is you never know who you’re going to stumble across.”

Sometimes, those encounters have been fruitless—like when a former movie producer named Steve Bannon pitched Rottenberg on turning his book on Jack Slade into a film. (“Some of the things he was saying were a little off the wall,” recalls Rottenberg, though he of course couldn’t have predicted that Bannon would become an alt-right provocateur who’d help Donald Trump W’68 ascend to the White House.) Others have been far more serendipitous—like when he was introduced to a woman named Susan Levin Seiderman, who would hire Rottenberg as the part-time editor of the free alternative weekly newspaper she had recently inherited control of—the Welcomat—in 1981 (see excerpt).

“How much of a risk did this career change pose to my career?” he writes. “Let me put it this way. In 1975 Philadelphia magazine’s annual ‘Best and Worst’ issue had pronounced the Welcomat the worst paper in Philadelphia.” But, as he’d done before in Chicago, Rottenberg worked out a deal permitting him to freelance part time. And “the most important inducement was Susan’s offer of near-total editorial freedom. ‘You can do whatever you want with the paper,’ she told me, ‘as long as you don’t bore me.’”

With limited resources, Rottenberg got creative and “completely revamped the paper’s format, so the whole paper became in effect like the op-ed page of a newspaper,” he writes, adding that he got the idea from the “Letters” section of the Gazette. In effect, he turned the Welcomat’s readers into its writers—and not much was off limits. “What I was doing at the Welcomat,” Rottenberg says today, “was really publishing the most outrageous piece I could find every week.”

Although it may have been a unique approach—and was popular among Philadelphians for that reason—it sometimes led to trouble. Rottenberg concedes that the “paper’s quality was wildly inconsistent from one issue to the next.” Looking back on it, he also doesn’t think he always “made it as clear as I should have” that he didn’t necessarily support or agree with an article even if he published it on the front page. But testing the limits of free speech was important to him—so much so that when the gay rights group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) protested with signs accusing the Welcomat of publishing “hate” following a 1990 column in which an author “scolded AIDS victims and abortion recipients for failing to exercise more control over their bodies,” per Rottenberg’s description of the column, “my response was you’re absolutely right,” he says. “That’s our idea—we’re getting the hate out in the open so everyone can look at it and label it for what it is. It was the precursor of today’s internet.” The difference, he adds, is “you could say whatever you want to say, but you had to be honest and you had to do it in a respectful and personal tone.”

Over the years, Rottenberg and the Welcomat fended off several libel suits and attempted advertiser boycotts. And he seemed to infuriate people of all political stripes. His memoir juxtaposes the ACT UP protests with a riveting chapter on his tussle with Philadelphia’s polarizing former mayor, Frank Rizzo, who once said of Rottenberg, “If I wasn’t a public figure, I’d rather make him eat a bundle of those articles covered with ketchup or mustard or whatever he likes.”

Rizzo had been out of the mayor’s office for a couple of years when he sued the Welcomat for publishing a 1982 essay by writer Noel Weyrich C’81 that included the line, “Frank Rizzo could not get elected in this atmosphere any sooner than a clown like Adolph Hitler could get elected in the Germany of today”—and later lumped Rizzo with Hitler and Mussolini. Unlike many libel suits, this one actually made it to trial, where Rottenberg took the stand in a Philadelphia courtroom to defend his newspaper’s right to freely express opinions about public figures. Rizzo also testified, and as Rottenberg recalls, it didn’t go very well for him as a lawyer presented examples of the former mayor using similar analogies to the one he was fighting. “The interesting thing is Rizzo was fond of shooting his mouth off, and he had this adoring fanbase where he could say whatever he wanted,” says Rottenberg, likening him to Trump in that respect. “When he finally got to court, it was a whole different world. He just looked kind of foolish.”

After the judge dismissed Rizzo’s suit, and the politician vowed to appeal the verdict, Rottenberg recalls in his memoir that he “walked over and introduced myself to Rizzo, whom I had never met before. ‘I want you to know that this decision changes nothing,’ I told him. ‘The judge’s ruling won’t change your opinion of me or mine of you. I respect your right to your opinion, and I hope you’ll respect mine as well.’ Rizzo, typically, missed my point. ‘Well,’ he replied, ‘I’m sure you don’t think I’m a Hitler.’”

As promised, Rizzo appealed the verdict, all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, where it was dismissed again, this time with comparatively little attention from media outlets that had initially pounced on the story, Rottenberg writes. “But for me, the satisfying outcome of this case reinforced the lesson” he had learned early in his journalism career: “Never let yourself be intimidated by someone else’s reputation.”

Like many of his generational peers, Rottenberg has found the internet to be both helpful and horrifying.

It plunged the knife into the heart of once-thriving newspapers that relied on classified ads like the Welcomat, which changed its name to Philadelphia Weekly around the time Rottenberg left in the mid-90s (and is now a digital-only publication that’s been through several editorial overhauls). His attempt to recreate the Welcomat’s magic by starting a new alternative weekly, with other Welcomat alumni, called the Philadelphia Forum in the late 1990s was short lived. And these days, the 80-year-old says he has no use for the heated discourse that populates social media, even if it bears some resemblance to the print forums he once fostered. “The Welcomat, the Philadelphia Forum was a curated conversation, and I was the gatekeeper,” he explains. As for Twitter? “I don’t want to go into that town square. It’s a waste of my time.”

Yet Rottenberg has evolved with the times, too. After short stints running Seven Arts magazine, the Philadelphia Forum, and Family Business magazine, he partnered with the University of the Arts to launch an online arts publication called Broad Street Review in 2005. Looking to find what he called his “personal holy grail: a highbrow Philadelphia audience,” Rottenberg aimed for BSR to “function as kind of a halfway house between conventional journalism and the unfiltered adolescent blogs then plaguing the internet.” And while he learned about the difficulties of monetizing such a venture, he also enjoyed the benefits of a digital-only publication (smaller budget, instant gratification, the ability to correct mistakes immediately). “I knew nothing about the internet at that point,” he says. “But once I did it, I said, Goodbye, print.”

Rottenberg ran BSR for about a decade—among his longest stints anywhere—and the website, billed as “Philly’s home for arts, culture, and conversation,” lives on today under different management. And though he’s no longer creating, revamping, or helming media outlets, Rottenberg doesn’t think he’ll stop writing any time soon, noting that his father and grandfather both worked into their 90s.

On his “bucket list” are book projects on the “Mungermen”—Penn football players who played under head coach George Munger Ed’33 from 1938 to 1953 in the glory days of Franklin Field [“Gazetteer,” Jan|Feb 2018]—and on a 13th-century ancestor who “had a confrontation with the Holy Roman Emperor.” (His interest in exploring genealogy dates back to his first book, Finding Our Fathers, in 1977.)

He also sometimes gives talks to younger journalists, as he did at Penn’s Kelly Writers House in April, believing at first that his book could serve as something of a lesson about adaptability and finding alternative ways to make it in a field he often hears is dying. “But I’m starting to wonder if that’s really true,” he says. “To do the kinds of things I have done, you have to have really thick skin.” (He needed one when a petition called for his firing from BSR after he wrote a ham-fisted column in 2011 on what women can do to avoid being sexually assaulted—which he later apologized for and devoted a chapter to in his memoir.) He also realizes others might not share his contrarian instincts.

“I get very uncomfortable whenever I’m around people who think they own the truth—because nobody owns the truth,” he says. “So my inclination is to take the other side, even if I don’t necessarily agree with it. It’s what I call the ignorance of certainty.”

Yet one theme of his book will likely ring true for any reader, of any generation, in any field. “You plant a lot of seeds in your life,” Rottenberg says from an office filled with his books on the shelves and his framed articles on the walls, “and you never know which ones are going to blossom.”

EXCERPT

“Whatever It Takes, Let’s Do It”

Princeton jabs, chance encounters, and refashioning the Welcomat.

Whenever the world seems to be conspiring against you, you might consider the invisible forces working in your favor. In the fall of 1980, for example, a presidential commission advised the US government to stop pouring federal dollars into the old cities of the Northeast and invest instead in the Sun Belt, where everyone seemed to be moving anyway. This report had nothing to do with me, of course—or so I thought at the time.

Shortly thereafter, Thacher Longstreth, then president of the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, angered local politicians and civic boosters by declaring that he agreed with the commission. At this point, I jumped into the act, writing a column in the Philadelphia Inquirer facetiously suggesting that Longstreth was merely the latest manifestation of an affliction that had plagued the world ever since Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton: an excess of graduates of Princeton University. That was the beginning of my relationship with Longstreth, which resulted in my collaborating on his memoirs ten years later.

More significantly for me, that column prompted a recent Princeton graduate, a Philadelphia lawyer named Linda Berman, to send me a good-natured note inviting me to lunch at the Princeton Club of Philadelphia. I accepted, and we became friends.

Some six months later, in the spring of 1981, Linda introduced me to Susan Levin Seiderman, a suburban housewife (as such women were then called) who had recently inherited control of the Center City Welcomat, a free weekly newspaper distributed in downtown office and apartment buildings as well as thousands of rowhouse doorsteps in downtown Philadelphia. This “shopper”—so-called because people read it mostly for the ads—had been launched in 1971 by Susan’s father, Leon Levin, not out of any interest in Center City but to protect his weekly South Philadelphia Review from competition on its northern flank. Although these two communities couldn’t have been more different—South Philadelphia was essentially Italian and provincial, whereas Center City had blossomed in the ’70s into a worldly hub of arts, culture, innovative restaurants, and upscale residents—for most of its first ten years the Welcomat remained literally identical to that of its parochial older sister, aside from a different front page.

Throughout that decade, Susan had implored her father to upgrade the Welcomat into a more sophisticated vehicle, but her risk-averse dad had stubbornly refused. Now Leon Levin was gone. Upon his death in 1979 he had bequeathed his primary earthly assets—his two weekly papers and their composition shop in South Philadelphia—to a trust for the benefit of his three quarrelsome daughters; but in his wisdom, Levin had given control to the youngest, pluckiest, and (to my mind) sanest of the three. That was Susan, who was now eager to fulfill her vision—what she described to me as “the Village Voice in Philadelphia”—but uncertain how to go about it. Her logic was refreshingly selfish and direct: “If I have to read this paper,” she told me, “I want it to be interesting.”

It happened that I had long nurtured a similar vision. As far back as the fall of 1968, in Chicago, I had corresponded with a few friends about creating a new kind of urban weekly. The publication I had in mind, I wrote, “could use the arts in one city as the springboard toward a journal of commentary in a wide range of fields.” My ideal location, I concluded even then, was Philadelphia:

Philadelphians are a rare combination of sophistication and provincialism; they’re interested in the arts but they’re very local-oriented, which is why I think a local magazine of the arts would succeed.

The phenomenon known as the “alternative press” had first surfaced in the mid-1960s as the “underground press”—an outlet for rebellious hippies and antiwar protesters eager to stick it to The Man. The thought of turning a profit never occurred to the scruffy but feisty founders of these haphazardly published papers, like the Seed in Chicago, the Boston Phoenix, or the Drummer in Philadelphia. You could say much the same thing about Chicago Journalism Review and its imitators that sprung up in twenty other cities. Making money wasn’t the point; speaking truth to power—or scribbling a poem while smoking a joint—was.

I spent much of the ’70s pitching my peculiar vision of a provocative Philadelphia alternative weekly to some half-dozen experienced male publishers, each of whom, in the best analytical male tradition, logically (and sometimes patronizingly) explained to me that no alternative paper had ever succeeded and therefore none ever would. In the mid-’70s, even Herb Lipson of Philadelphia magazine tried and failed to start a weekly paper in Center City. And now here was Susan Seiderman, who at 43 possessed little journalism experience and looked more like a fashion model than a publisher. As we talked over lunch in a cramped and noisy Center City seafood house, Susan’s situation reminded me of Katharine Graham’s at the Washington Post after her husband died—a neophyte who decided to make the most of her inheritance and wound up improving it beyond the dreams of her father and husband.

When I encouraged Susan, in effect, to risk her family’s inheritance on my unproven concept, she listened sympathetically. “This is what I want to do,” she announced when I finished my pitch. “Whatever it takes, let’s do it!”

Excerpted from THE EDUCATION OF A JOURNALIST by Dan Rottenberg. Copyright © 2022, Redmount Press. Edited for length and reprinted with the author’s permission.