A career in sports PR—filled with lessons from legendary coaches—culminated at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

When Harvey Greene C’75 was an undergraduate at Penn, he majored in chemistry and envisioned a career as a researcher.

Sure, he loved sports, having grown up a vociferous fan in Queens, just a few miles from Shea Stadium, idolizing the likes of Joe Namath and Tom Seaver. And yes, he dabbled in play-by-play for WXPN, broadcasting football, basketball, hockey, and soccer. But Greene, the radio station’s sports director, felt his professional calling was being a chemist, and he had already been accepted into Rice University’s PhD program for organic chemistry. That was until one fateful day when his close friend and WXPN broadcast partner Larry Wahl W’75 showed him an article in the Wall Street Journal about two master’s programs in sports administration, at the University of Massachusetts and Ohio University, respectively.

“That day was the single most important day in my life, other than meeting my wife,” Greene says.

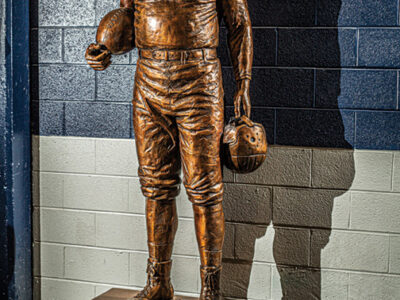

Greene headed off to UMass following graduation—and his journey to the Pro Football Hall of Fame was officially launched. In a ceremony in June, Greene gained recognition in the Hall of Fame’s “Football Support” wing by winning an Award of Excellence for his longtime work as a public relations director for the Miami Dolphins.

Although Greene’s official title had become senior communications executive, he much prefers the moniker of public relations. “You have to earn the trust of players and coaches to be able to work with them and establish a healthy relationship between the team and the media so they cover the team fairly and accurately,” he says.

Over an illustrious 45-year career, Greene has led public relations departments for teams in three different pro sports leagues: the Dolphins of the NFL; the NBA’s Cleveland Cavaliers; and perhaps the most iconic franchise in sports, the New York Yankees of MLB. (Interestingly enough, his WXPN partner Wahl was Yankees owner George Steinbrenner’s fourth PR director; Greene was number nine.)

Working under the mercurial Steinbrenner, Greene notes he was “fired” five times. “Each time he fired me, he basically was just letting off steam. The first two times it happened, I really thought I was fired. After that, I knew better, ignoredit, and just showed up to work the next day,” he chuckles.

“I got fired for strange reasons, including once for not accompanying Billy Martin and Mickey Mantle to a nightclub after a loss in Arlington.”

If there was a Hall of Fame for storytelling, Greene would be in it. His voice, still thick with a New York accent despite decades living in Florida, recalls events, relationships, and interactions with excitement, enthusiasm, and painstaking detail. In fact, the best way to tell the story of Greene’s ascension in the sports business is through the lessons he’s learned—starting at Penn.

During his senior year in 1975,Penn boasted a loaded men’s basketball team led by future NBA draft picks Ron Haigler C’79 GEd’99 and Bob Bigelow C’75. Toward the end of the regular season, the Quakers barely scraped by a mediocre Columbia team by three points. Greene criticized Penn head coach Chuck Daly on the air for not having his team ready to play, saying they should’ve won by 20. The comments got back to Daly, who vowed he’d never talk to Greene again—which the coach adhered to, putting Greene, the Quakers’ play-by-play man, in a tough spot.

Fast forward to 1993. While working for the Dolphins, Greene ran into Daly who by then had coached the Detroit Pistons to two NBA titles and the US “Dream Team” to an Olympic gold medal in 1992. Daly remembered him and his criticism. Greene broke the ice by saying, “I figured you knew how to beat the Lakers and win the Olympics. I just didn’t think you knew how to beat Columbia.” Daly cracked up, and the two would go on to become friends.

The lesson: “Don’t criticize anyone if you don’t know what you’re talking about, and as a college senior I never would’ve thought about it that way,” Greene says. “I used that later in my career when a writer would criticize a player or coach—I’d say, ‘You should have talked to them directly about it first.’”

Of the myriad accomplishments Greene has achieved in his career, perhaps nothing is more impressive than surviving working for some of the toughest figures in sports: Steinbrenner, Yankee managers Lou Piniella and Billy Martin, and the Dolphins’ Don Shula, Nick Saban, Jimmy Johnson, and Bill Parcells.

“The people I worked with were so demanding there was no margin for error,” Greene says. “If you can practice these three precepts—be prepared, don’t make excuses, maintain your integrity—then you can build trust and respect of the people you work for and you can work in any sport or any profession.”

As the head coach of theonly undefeated team in NFL history, the 1972 Miami Dolphins, Don Shula’s mantra was the winning edge. Greene quickly learned what that meant when he went to work for the Dolphins in 1989.

Greene—an avid runner who’s completed 13 marathons—was jogging around the practice field with Shula and cut inside the lines as he made a turn. “Shula bellowed, ‘Run the whole goddamn field,’ and he was serious,” recalls Greene. “And that’s how I learned what the winning edge meant—no shortcuts, do the work you have to do, and find the one little thing that nobody else is doing. I learned Shula’s philosophy of success running around the football field.”

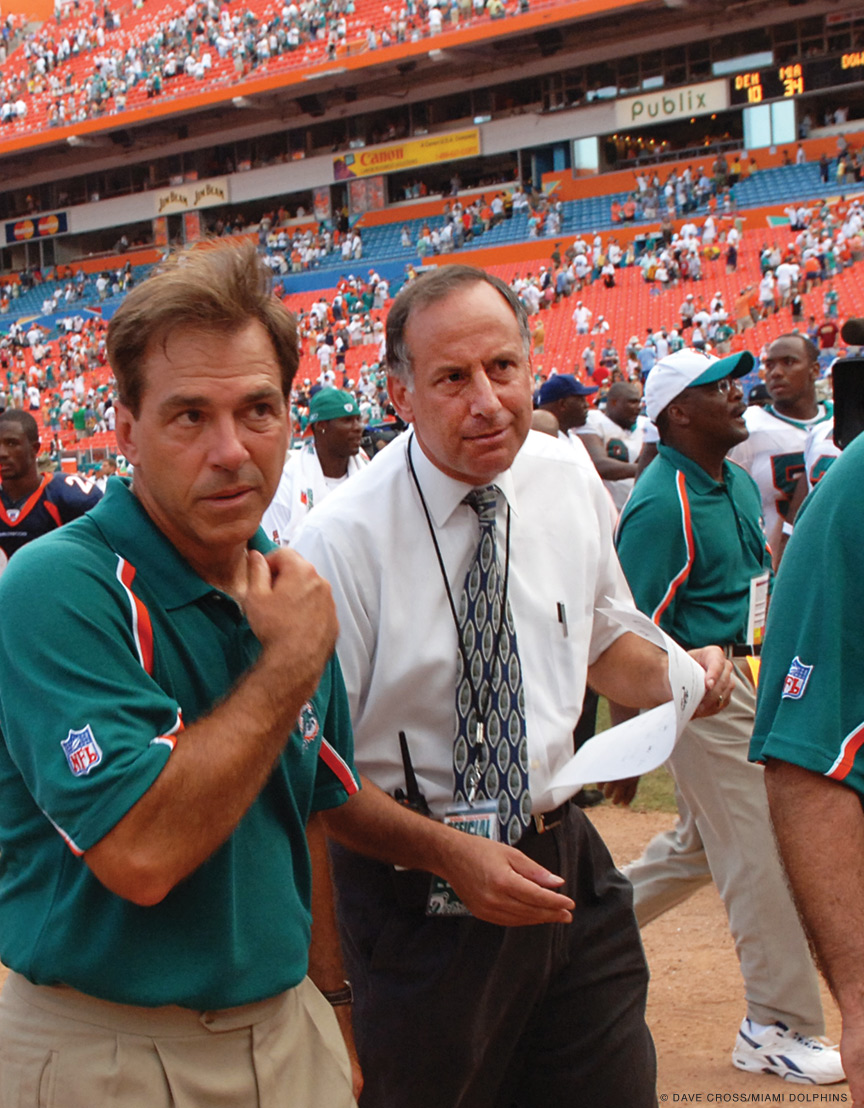

If Greene learned from Shula that you can’t do too much, from Nick Saban he learned you can talk too much. In 2005, not long before Saban left the Dolphins to begin his remarkably successful tenure at the University of Alabama, Greene was summoned into Saban’s office “to let me know he was upset after reading a negative article about a player that he thought I should have prevented,” Greene says. “I started to say I had nothing to do with the story, but he cut me off. He said, ‘Your actions speak so loud I can’t hear a word you’re saying.’ I realized he didn’t want to hear any excuses; he just wanted to hear, Coach, I’m sorry, I’ll make sure that never happens again.”

Greene was always a quick study but the lesson he learned about the importance of looking ahead and not back almost cost him his job. Jimmy Johnson came to the Dolphins as the first head football coach with both a college national championship and Super Bowl rings. In 1999, after the Dolphins had a huge win on Monday Night Football, Johnson was concerned about all the “attaboys” his team was getting from the media without much focus on the next game—which Miami would lose big.

“Jimmy was notorious for his temper and ripped the entire team after the game but saved his worst for me,” Greene recalls. “It was the only time I really thought I was going to get fired.”

Johnson told Greene that he didn’t want to hear a word from the players unless it was about their upcoming opponent, so for the rest of the week, Greene and his staff monitored every word of every interview. The Dolphins prevailed against New England and Greene felt relief and redemption—though was playfully rebuffed by Johnson when he asked for the game ball as a reward for helping get the team back on track.

Greene gained a nickname, along with a lesson, from two-time Super Bowl champion Bill Parcells, who joined the Dolphins in 2008 to run the team’s football operations. Miami had a player who had just run into some legal issues so Parcells called in Greene to talk about how to handle that situation publicly. “There are going to be a lot of times, including now, when we have to deal with three-alarm fires,” Greene recalls Parcells telling him. “Your job is to turn them into one-alarm fires, not five-alarm ones.” Greene never forgot that advice, and Parcells nicknamed him his “fireman.”

When Greene was honored by the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, he realized how much he was shaped by those men who often made his life difficult. “Without the lessons I learned from them, there’s no way I would’ve been as successful as I was in my field,” he says. “In fact, after I won the award, I sent thank you notes to [Don’s sons] Dave and Mike Shula, Jimmy Johnson, Nick Saban, and Bill Parcells for the lessons they taught me that served me well during my career. I also made it a point to thank [Dolphins Hall of Famers] Dan Marino, Zach Thomas, and Jason Taylor for their trust in me.”

Taylor calls Greene “the one constant” during his 15-year playing career that he mostly spent with the Dolphins. “Harvey seemed to know how to handle every situation, whether it was after a big win, a league honor, or a major crisis,” Taylor says. “When it comes to PR guys, Harvey was as good as it gets.”

Greene’s public relations work has taken him beyond Super Bowls, World Cups, and the Olympics. Throughout his NFL career and following his retirement from the Dolphins in 2017, Greene has been a press lead for the Clintons and Bidens, in charge of the press logistics and the imagery that comes from their public events.

He’s been to 18 foreign countries including meetings with heads of state like Angela Merkel and Benjamin Netanyahu, and global leadership events like NATO and G7 summits. Most recently, he accompanied President Joe Biden Hon’13 and Jill Biden to Normandy for the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

But Greene has always remained that rabid sports fan from Queens, still marveling that his career enabled him to meet his childhood idols like Namath and Seaver, who turned out to be “great guys.” Perhaps the greatest lesson the public relations maven learned, after all, is that success is all about cultivating relationships.

—Andrea Kremer C’80

Editor’s Note: Andrea Kremer C’80 and Harvey Greene C’75 are two of four Penn alums who have been recognized by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Kremer is enshrined in the Hall’s media section for winning the Pete Rozelle Radio–Television Award in 2018 for her broadcasting career. The other two are Philadelphia Eagles great Chuck Bednarik Ed’49 and former NFL Commissioner Bert Bell C1920, both of whom have their busts displayed in the main section of the Hall that honors former players, coaches, and executives.