Class of ’20 | When Upton Bell saw the brown suit, he knew. Dropping his friend’s binoculars, the 21-year-old barreled down a few steps, hopped a railing and raced across Franklin Field, reaching the south stands of the venerable stadium breathless and scared. Pandemonium immediately engulfed him. Hundreds of people surrounded a motionless man, oblivious to the go-ahead touchdown that had just been scored by the Philadelphia Eagles’ Tommy McDonald.

“That damn brown suit,” Upton knew, was the one that his father, DeBenneville “Bert” Bell C’20, commissioner of the National Football League, always wore in the fall. Hours later, Bert Bell died.

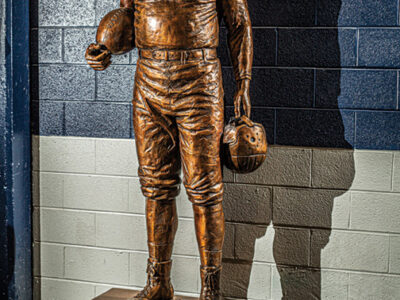

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Bell’s death, and, for many, the details surrounding the football legend’s passing have a certain rough poetry. His last day on earth came inside a stadium where he once starred as a University of Pennsylvania quarterback, while watching a game between two teams he once owned (the Philadelphia Eagles and Pittsburgh Steelers), in a sport he transformed from circus sideshow to American obsession. He even suffered the massive heart attack just as the winning touchdown was scored. “It was like it was ordained from God,” says journalist Bob Lyons, author of On Any Given Sunday: A Life of Bert Bell.

But for one sad son, it’s often been hard finding solace from that Eagles-Steelers game on October 11, 1959. Moments before kickoff, Upton had nudged his way through a crowded Franklin Field office to ask his father for tickets and a little extra cash. The most powerful man in the NFL obliged and then said, “See you after the game.”

“I never had a chance to say good-bye. I’ll never forget that,” says Upton, a talk-radio host and former general manager of the New England Patriots. “Some people think it’s a fantastic ending to a great life, but they’re not his children.

“Well, it was a fantastic ending,” Upton acknowledges. “He didn’t suffer. He went probably the way he would have wanted to go. But for someone who was growing up, during the period of life when you really need a father, the person I needed was gone.”

That feeling of loss, while most profound in the Bell family, hit the entire country hard. Bert Bell, who served as NFL commissioner from 1946 until his death in 1959, was a football celebrity before there were football celebrities, a stabilizing force in a sport that often teetered towards irrelevancy.

Among his many accomplishments as an NFL coach, owner, and commissioner were starting the amateur draft, creating sudden-death overtime, and bringing the sport to television sets across the country—staples of the modern game, all. He made the NFL the dominant professional football league by absorbing three teams from the All-America Football Conference (the Cleveland Browns, the San Francisco 49ers, and the Baltimore Colts), established strong anti-gambling controls, and even coined the popular phrase, “On any given Sunday, any team can beat any other team.”

Born in 1895 to a prominent Main Line family, Bell never had a choice when it came to college, as his father, Pennsylvania attorney general John Cromwell Bell L1884, was fond of saying, “Bert will go to Penn or he’ll go to hell.” The politician’s son obeyed, enrolling at the University in 1914.

“He hated being from high society; he didn’t want anything to do with that stuff,” says Lyons. “He was a football guy. He walked with a swagger and talked out of the side of his mouth.”

Bell was a good football player, too. As a quarterback, punter, punt returner, and defender, he played four years on varsity, leading Penn to its first and only Rose Bowl in 1917. After graduation he stayed around the game as an assistant coach at Penn and Temple for the better part of the next decade. It wasn’t until 1933 that Bell left the comfortable confines of college football for the treacherous world of professional football, buying the rights to a defunct NFL franchise, the Frankford Yellow Jackets, with three former teammates—for $2,500.

They decided to rename the franchise the Philadelphia Eagles—a team that would go on to capture the spirits and break the hearts of Philly fans for the next eight decades. But at the time, the investment seemed like a recipe for disaster: about 90 percent risk mixed in with 10 percent stupidity.

“The city was suffering through the Depression, just like the country was,” Lyons notes. “And when he bought the team, the league was really struggling.”

From 1933 to 1936, the Eagles bled so much money that Bell had to buy out his partners. From 1936 to 1940, as sole owner and head coach, Bell guided the Eagles to only 10 total wins. But with the moral and financial support of his new wife, famed Broadway actress Frances Upton, he never entertained thoughts of leaving pro football. In 1940, he sold the Eagles and became co-owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Six years later, he sold the Steelers and was elected commissioner of the NFL, where his innovations would shape the league and launch him into the Hall of Fame.

Perhaps Bell’s crowning achievement came in 1958 when the Baltimore Colts faced the New York Giants in the NFL Championship Game at Yankee Stadium. In front of a television audience of about 45 million, the game went into sudden-death overtime, with the Colts winning in dramatic fashion, 23-17. After the game, a tearful Bell was quoted as saying, “This is the greatest day in the history of professional football.” He was not alone in that assessment.

“I think, more than anyone else, he realized the significance of that game,” says Mark Bowden, author of The Best Game Ever: Giants vs. Colts, 1958, and the Birth of the Modern NFL. “His proposal of sudden-death overtime bore its fruit in such an exciting way and he had pushed the game into primetime on Sunday night … After that, everything just started skyrocketing.”

The celebrated Colts-Giants game was the last NFL championship Bell ever saw. Less than 10 months later, Bert Bell put on his brown suit, walked into Franklin Field and, for the final time, stood over the league he had nurtured from infancy.

—Dave Zeitlin C’03