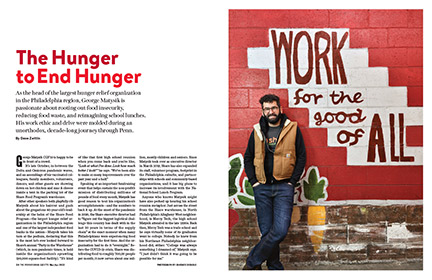

As the head of the largest hunger relief organization in the Philadelphia region, George Matysik is passionate about rooting out food insecurity, reducing food waste, and reimagining school lunches. His work ethic and drive were molded during an unorthodox, decade-long journey through Penn.

By Dave Zeitlin | Photography by Candace diCarlo

George Matysik CGS’10 is happy to be in front of a crowd.

It’s late October, in between the Delta and Omicron pandemic waves, and an assemblage of his vaccinated colleagues, family members, volunteers, donors, and other guests are chowing down on hot chicken and mac & cheese inside a tent in the parking lot of the Share Food Program’s warehouse.

After other speakers both playfully rib Matysik about his haircut and gush about the gregarious 40-year-old’s leadership at the helm of the Share Food Program—the largest hunger relief organization in the Philadelphia region and one of the largest independent food banks in the nation—Matysik takes his turn at the podium, declaring that this is the most he’s ever looked forward to Share’s annual “Party in the Warehouse” (which, in non-pandemic times, is held inside the organization’s sprawling 190,000-square-foot facility). “It’s kind of like that first high school reunion when you come back and you’re like, “Look at what I’ve done. Look how much better I look!’” he says. “We’ve been able to make so many improvements over the past year and a half.”

Speaking at an important fundraising event that helps sustain the non-profit’s mission of distributing millions of pounds of food every month, Matysik has good reason to tout his organization’s accomplishments—and the numbers to back it up. At the onset of the pandemic in 2020, the Share executive director had to “figure out the biggest logistical challenge this country has dealt with in the last 50 years in terms of the supply chain” at the exact moment when many Philadelphians were experiencing food insecurity for the first time. And the organization had to do it “overnight.” Before the COVID-19 crisis, Share was distributing food to roughly 700,000 people per month; it now serves about one million, mostly children and seniors. Since Matysik took over as executive director in March 2019, Share has also expanded its staff, volunteer program, footprint in the Philadelphia suburbs, and partnerships with schools and community-based organizations, and it has big plans to increase its involvement with the National School Lunch Program.

Anyone who knows Matysik might have also perked up hearing his school reunion metaphor. Just across the street from the Share warehouse, in North Philadelphia’s Allegheny West neighborhood, is Mercy Tech, the high school Matysik attended in the late 1990s. Back then, Mercy Tech was a trade school and he says virtually none of its graduates went to college. Nobody he knew from his Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood did, either. “College was always something I dreamed of,” Matysik says. “I just didn’t think it was going to be possible for me.”

So if he were to gather with any of his old high school classmates for a reunion, they might be stunned to learn about Matysik’s unconventional journey—and all of the sleepless nights and bathrooms mopped on his decade-long quest to graduate from an Ivy League university and set himself up to fight for a city he’s always believed in as much as himself.

Doug Moak C’06 remembers the thick Philly accent. And the suits. Those three-piece suits that Matysik plucked off a five-dollar rack at a Kensington Avenue thrift store and wore to the Introduction to Urban Research class they took together. “I wasn’t friends with him then,” Moak recalls. “But I thought he was an interesting character.”

Over time, the two would become close. And one night, while stumbling home from a happy hour after an event for a political campaign they were both interning for in 2006, Matysik revealed a secret to Moak. Although he was a year behind him at Penn, Matysik was actually a few years older than Moak and was balancing a full-time job while pursuing a degree in Penn’s College of General Studies (CGS)—which was renamed the College of Liberal and Professional Studies (LPS) in 2008. The full-time job? He worked as a janitor in College Hall. Or, as Matysik expressed it to Moak that night, “I’m the guy who cleans Amy Gutmann’s toilet.”

Those three-piece suits he wore to his night classes, Matysik says now, were his way of drawing a contrast with the custodian jumpsuits he wore during the day. “I think that was some of my own insecurities,” he reflects. “I was wearing my uniform from 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. and was treated one way. Then I’d throw this thrift store suit on and I’d be treated another way.”

Matysik didn’t think he’d be living a dual life when he graduated from Mercy Tech in 1999. Intent on joining an electrician’s union, he changed course when he heard about a different union job as a Penn janitor. He started cleaning College Hall in the fall of 1999, and two years later began to take advantage of an employment benefit permitting Penn employees to take free classes. At first, he says he could only take one per semester, “which was driving me nuts.” But in 2003 he upped his course load. “That’s when I was pretty much a full-time student and a full-time janitor at the same time.”

He enjoyed his urban studies major and college life, but it didn’t come easy. Once during a storm, he remembers shoveling snow all day before having to go into a history class at Bennett Hall, still in his soaked uniform. Evening classes were a necessity but he could barely keep his eyes open when they dimmed the lights in an astronomy course, about 14 hours after he began his early-morning janitor shift. And he couldn’t start his homework until about 9 p.m., generally using a computer in a lounge inside the Towne Building in the engineering school, to which his janitorial assignments had been shifted from College Hall. “I had never used a computer before in my life until I got to Penn,” says Matysik, who banged away on the keyboard with two fingers. Writing papers late into the night, he’d often sleep in the lounge—which some fellow custodians came to know as “George’s Lounge”—rather than trek back to his house on 51st Street (which he had purchased for $30,000 with assistance from Penn’s Enhanced Mortgage Program for employees and rehabbed with his trade school buddies). There, he’d jockey with other students for a couch, trying not to lose his spot when he went to the bathroom. Another housekeeper, who became a motherly figure to him, often roused him from his slumber at the crack of dawn, whereupon Matysik would grab a shower at Pottruck gym and a coffee at Dunkin’ and begin cleaning the same building he had just slept in.

“When someone is on a track and they choose to go in a radically different direction from the track that’s been laid out for them, I think that takes a lot of courage,” says Moak, who’s remained good friends with Matysik. “He was always putting in work that was really beyond what I did, or what my other friends did—or anything I had seen from another Penn student.”

Matysik’s life got even more hectic when a Penn office manager who knew of his interest in politics suggested he work for her brother Joe Sestak’s congressional campaign. “So in the fall of 2006,” he says, “I was a full-time housekeeper, a full-time student, and a full-time campaign worker at the same time. That was probably the most insane thing I ever did.” But, he adds, it was also “one of the most meaningful and important things,” as he met his wife on that campaign and stayed in politics for the next few years, leaving his janitor job and delaying his Penn graduation from 2007 until 2010.

By the time he walked in Commencement, without any of his friends, he says it was more of a relief than anything—but a proud moment still. Only a couple of other housekeepers that he knows of have followed a similar path to graduation—most famously, Dan Harrell CGS’00, who mopped floors at the Palestra for many years [“Gazetteer,” Sep|Oct 2012] and carried a mop at his Commencement.

“There was so much education I was getting beyond what I was learning in the classroom,” Matysik says. “Seeing how differently I would be treated as a person if I was wearing my housekeeping uniform or carrying my bookbag around, I would feel that in a very real way.” To this day, he still is grateful to John Fry, the former Penn executive vice president (and current Drexel University president), for always stopping to greet him when he was cleaning offices, whereas others acted like “I literally didn’t exist.” He also occasionally sensed a feeling of resentment from other janitors or supervisors, who would angrily question why he was on a computer in a student lounge—assuming that he was still on the clock when in fact he had punched out. “There was always that duality of living in these two worlds,” says Matysik, whose humble Northeast Philly roots prepared him for navigating different worlds.

Matysik’s work ethic and drive took shape early in his childhood, often to the exasperation of his parents. Growing up in Oxford Circle, “an old-school, kick-the-can kind of neighborhood” in Northeast Philly, he once set up a baseball card sale at six in the morning on the street, where his aunt found him and dragged him back to his house. (He was only six or seven at the time.) He’d sell soft pretzels on the corner and started working at a gas station when he was 11, which he laughs was “probably against a lot of child labor laws.” He cut grass and shoveled snow for his neighbors and extended family. He made a newspaper called the Kidquirer, which he tried to sell when he wasn’t delivering real copies of the Philadelphia Inquirer with his father on their 5 a.m. paper route through Mayfair. “I was a very entrepreneurial kid,” he says. “I had so many little schemes I was always doing. It got me in a lot of trouble, too.”

While his schemes were as much about finding creative outlets as turning a buck, sometimes money was tight at home. “We’d have really great Christmases and incredibly lean Christmases,” he says. “There were times I’d go in the fridge and everything would be in there and times I’d go in the fridge and there was nothing. We grew up with government programs.”

Matysik recalls the family going through especially tough times when his younger sister was born with a rare disability that caused blindness and other health problems. The oldest of three, Matysik was eight years old at the time and cried when he found out. “But it ended up being the biggest blessing my family ever got,” he says. “It brought us a whole other level of empathy. Her birth is probably one of the most impactful things—if not the most impactful—that happened in my life.” He adds that it “definitely drove me to want to do good things—whatever that looks like. But as an eight-year-old, you don’t know what that is.”

Just as it was hard to imagine what he might be when he grew up, it was also hard to imagine life outside his tight-knit community, where everyone seemed to know everyone. “The whole neighborhood was looking out for each other,” he recalls. “It was a special environment for me to grow up in.” But it also felt very contained and distant from downtown. All he knew about Center City was going to the Christmas Light Show and Dickens Village and seeing the “iggle” statue in the Wanamaker Building during the holidays, just as all he knew about Penn was going to Big 5 games at the Palestra with his father, a Teamster for more than 50 years.

Attending Penn as a student opened his eyes to new possibilities—and schemes. Having never shaken that feeling of food insecurity from his youth, he’d sometimes sit in on different lectures and attend events just for the free meal served afterwards. Other times, in between mopping floors and writing papers, he’d stop to watch engineering students work in a robotics lab, admiring their ingenuity. He became president of the student council for the CGS Student Advisory Board, where he helped working professionals and other nontraditional students gain access to grad-school lounges so they could hang out with people closer to them in age.

More than anything, he felt like his urban studies courses gave him the “tools” as well as the desire to help Philadelphia. “I always wanted to do work to make my city a better place,” he says. And the city felt manageable enough to make “a very real impact.”

Politics initially seemed like the best way to do that, and after working on a few campaigns he launched one of his own, running for city council in 2014. But it only lasted a couple of months. Something about campaigning for himself, telling voters “I am the answer,” didn’t sit well with him. “I felt uncomfortable the entire time, called off the campaign, and refunded everyone their money,” he says.

The non-profit world proved to be a better fit, and the food insecurity he’d known as a child pushed him into the hunger relief sector. He worked at the food bank Philabundance in a variety of roles for almost seven years, as it grew into a big name in that space. (“Even though Share distributes way more food than they do, they’ve got a brand I think people recognize,” he says now.) In 2015 he left Philabundance to run the Philadelphia Parks Alliance, where he focused on building programming at 150 recreation centers and “creating a sense of community” across different parts of the city.

Not long before that, he also established the Friends of Mifflin School, a neighborhood non-profit group designed to raise money for the elementary school near his home in East Falls. “One of the most illuminating parts of that was getting to understand some of the big systemic issues we’re dealing with in this city” in terms of what is and isn’t being funded at Philadelphia public schools, he says. And a lot of that has stayed with him as he’s positioned Share to provide food for many Philadelphia-area schoolchildren through its involvement with the National School Lunch Program, which was established under the National School Lunch Act of 1946 to provide low-cost or free lunches to what is now more than 30 million students each day. “Those were issues I feel like I had been tackling around the edges for 15, 20 years,” he says. “Now I might be in a position to be able to have a really significant impact.

“I’m really hoping that Share Food Program is an organization that is going to change the way school lunch looks—hopefully not only in the city of Philadelphia but potentially throughout the country.”

The first organized school lunch program, Matysik proudly points out, actually began in Philadelphia in the late 1890s. From then until the middle of the 20th century, programs were generally run by philanthropic groups before “these big for-profit businesses realized there’s money in schools,” which led to a decrease in quality, Matysik says. “What we’re building toward is trying to disrupt that system in a lot of ways. How do we put the dollar signs off of those kids?”

Share’s involvement with the program began three months after Matysik started in 2019, and through it the organization currently provides food for about 300,000 children in nearly 800 schools in Philly and its four collar counties. “As the only non-profit in the country that manages this program,” he says, “we’re able to make sure we’re prioritizing more nutritious food.”

With its large fleet of trucks, Share had the logistical operations in place to get the food to schools. But it had to expand its freezer space to accommodate its share of the food supplies—about 30 percent overall—provided to districts that qualify for the federally assisted meal program. Matysik hopes to push that far closer to 100 percent, while working with the USDA to get healthier food to schools at no extra cost—and perhaps, in the process, create a model for childhood nutrition that can be replicated across the country. But to do that, “we’ll need more freezer space, we’ll need more trucks, we’ll need a production kitchen, more staff,” he says. “That’s the biggest investment we as an organization need to look at.”

With that and other future projects in mind, Share is eyeing a major capital campaign to renovate its warehouse, which was originally built in the early 1900s to be a ball-bearings factory. Matysik says that Share began leasing it about 35 years ago after the organization was founded in 1986 as a food co-op—“when the idea of food deserts wasn’t even fully developed yet but we were going out and purchasing food and reselling it to communities that didn’t have access.” In 1991 Share pivoted to be a food bank, redistributing its product through a network of food pantries, and about a decade ago it purchased the building—which, in addition to storing food, serves as a command center where more than 1,000 volunteers pack boxes for seniors. The building renovations, Matysik says, will not only increase storage space but improve the volunteer and staff experience with modern amenities including an event space on a green roof. “It will definitely be a game changer for us,” he adds.

Tracey Specter C’84 LPS’18—who joined the Share board the same year Matysik took over as executive director and became board chair in June 2020—believes her fellow Penn alum is “always very forward-thinking, very strategic” when they discuss plans. And he manages to keep a firm eye on the future even as each day presents new challenges. When the pandemic first struck, “he didn’t take a day off for months,” Specter recalls. “He was working seven days a week, I don’t even know how many hours a day, just because he knew the need was so high. I really had to insist at some point he take off and recharge.”

Fortunately for Matysik, he had booked a $1.5 million purchase in the last week of February 2020, which helped Share navigate the earliest—and scariest—days of the pandemic. (Share’s food comes from government partners, supermarkets, wholesalers, restaurants, farms, food drives, and other sources.) And since then, he’s been able to lean on a much larger staff, having quadrupled Share’s full-time workforce during his tenure.

One of the roughly 60 staffers is Kayla Brown SPP’18, who began at Share in October as its deputy chief program officer overseeing programs at Nice Roots Farm (where Share harvests up to 2,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables annually and educates college students—including from Penn—in urban farming) and Philly Food Rescue (which Share acquired last summer, to use its technology to find and preserve food across the city that would normally be thrown out). She also supervises the volunteers who pack their personal vehicles with 30-pound boxes to make direct deliveries to homebound, low-income, elderly people. In addition to the food that Share brings to senior sites throughout the region, these additional “Knock, Drop & Roll” deliveries, which began at the onset of the pandemic, have allowed Share to service “those who need nutritious food but aren’t able to make it to a pantry” because of their health or COVID-19 fears, Brown says.

Daphne Rowe C’79 G’97 is one of the volunteers who drives boxes of food to seniors. And Rowe, who’s worked in philanthropy for more than 40 years, has been impressed with Matysik from afar—particularly how he replaced Steveanna Wynn, who ran Share from 1989 and 2018, with “great tact and sensitivity,” Rowe says. “Steveanna was a wonderful advocate in the hunger space. She was a very hard act to follow, and he was actually the perfect candidate.”

Specter agrees, calling Wynn, who died last April at 74, a “bigger than life” figure who left Matysik “big shoes to fill.” But he’s done so, she adds, with tenacity, thoughtfulness, and heart. “He’s super empathetic,” Specter says, “and very personable. He’s one of those people you just want to be around.”

Sometimes, Matysik laughs, he’ll be around too much. Still an early riser, he arrives at the warehouse at 4:30 a.m. some days, “just to talk to whoever, and that gets me in trouble sometimes”—another carryover from his janitorial days. “It’s always been a place with open doors,” he adds, which is something Brown has come to appreciate. “He invites all of us: not just senior-level staff, any staff, any volunteer, anyone who’s involved, to give feedback,” Brown says. “If we can sell him on why we need something, he’s pretty much going to make sure we can get it done.” Other times, he’ll just want to crack jokes, give restaurant recommendations, or, for some reason Brown still hasn’t figured out, talk about barracudas. “I find myself to be a super high-energy person, but his high energy is way more extreme than mine,” she says. “You walk into the office and you just hear him. You’ll hear him before you see him.”

Matysik’s hands-on leadership style will continue to be critical as new opportunities and challenges await. The pandemic’s persistence has not only led to a sharp rise in the number of hungry Americans but continued supply chain difficulties. (“I could decide today I need a new truck and I might be looking at 2023 when I can get something on our lot that we own.”) It has also mandated less face-to-face interaction for volunteers who drop off food at the door rather than bringing it inside. “I hate having to make changes like that,” he says. Other changes are more exciting—such as the 8,000-square-foot warehouse Share recently purchased in Delaware County to provide food to the 15 pantries it partners with there. (Share is the lead agency for state and federal food distribution in both Delaware and Montgomery counties, where it is also looking for warehouse space.) And a partnership with DoorDash will facilitate faster home deliveries—while painting a vision for how Share, which Specter calls a “transportation organization,” might continue to grow over the next decade. “Our competition, to me, isn’t necessarily the other food banks in our space,” Matysik says. “It’s how can we deliver the same level of service as if you went on Amazon right now and ordered a Whole Foods cart?” One of Share’s primary missions has always been to break down barriers between the “haves and the have nots,” he adds, while prioritizing racial equity, education, and food justice advocacy.

“Philadelphia is the largest hungriest city,” Specter says. “And it shouldn’t be. We should not be in that position. I really feel we are on track to change that.”

For all of his city’s problems, Matysik wouldn’t want to help feed his neighbors anywhere else. It’s where he grew up an entrepreneurial kid in the Northeast, discovered unexpected opportunities in University City, came full circle in Allegheny West, and has roamed food pantries and warehouses and restaurants all throughout, discovering stories of struggle and hope along the way.

“No matter what part of the city you’re in,” he says, “it always feels like home.”

This was a wonderful article, well written, interesting, and inspiring! Matysik has overcome so much adversity, and I was proud that Penn’s College of General Studies, now the College of Liberal and Professional Studies (LPS), provided him with the opportunity to earn a college degree. I am sure that LPS has many similar success stories to boast about. Why not publish an article about LPS?

From the moment he arrived at Philabundance we knew that George was a force to be reckoned with. He came to us from Joe Sestak’s successful Congressional campaign office and created our office of Government Relations. It was a new area for Philabundance and George made it important. When we created Fare & Square (the first nonprofit supermarket in the county) in Chester, George was a critical element in getting the city of Chester to buy in. What he has accomplished at Share is nothing short of incredible and our area is better off for it.