By Richard L. Kagan

University of Pennsylvania Press, 392 pages, $69.95

A new biography of Penn benefactor Henry Charles Lea paints the Philadelphia publisher, activist, real estate investor, and amateur historian as an exceptionally well-tutored man.

By Dennis Drabelle

First-rate scholarship by amateurs used to be a common feature of American intellectual life. Constance Rourke did not have a PhD in history or any other field; her 1931 book, American Humor: A Study of the National Character, has been republished as a New York Review of Books Classic. Bruce Catton never completed his undergraduate work, but A Stillness at Appomattox (1953), the final volume of his Army of the Potomac trilogy, won both a Pulitzer Prize in History and a National Book Award for Nonfiction. The degreeless polymath Lewis Mumford wrote some of the 20th century’s most trenchant social criticism.

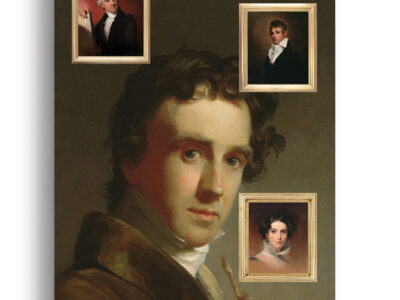

Henry Charles Lea, the subject of Richard L. Kagan’s astute new biography, was a precursor to those worthies [“Lea’s Legacy,” Mar|Apr 2014]. Though educated entirely at home by a tutor, Lea wrote such a comprehensive history of the Spanish Inquisition that, in Kagan’s opinion, virtually all subsequent treatments are “best seen as a gloss on this foundational work.”

Born in Philadelphia in 1825, Lea was the child of a mixed marriage—Quaker on his father’s side, Catholic on his mother’s. The adult Henry married his Episcopalian first cousin Anna C. Jaudon; he ended up a Unitarian. The couple’s consanguinity had riled their parents less than their ages when they first tried to wed: he was 17, she a year younger. Bowing to familial pressure, they waited seven years before tying the knot.

Young Henry had dabbled in conchology, the study of mollusks, and written poetry that, judging from the samples provided by Kagan, was derivative and bland. Again complying with his elders’ wishes, Henry reluctantly joined the publishing house founded by his maternal grandfather, Mathew Carey. Lea went on to run the firm and make the profitable decision to specialize in publishing medical books and journals. His shrewd investments in Philadelphia real estate made him one of the city’s richest men.

He wanted something more, though—recognition as an intellectual—and suffered periods of despondency exacerbated by overwork and frustrated ambition. In his spare time, he read voraciously, notably in medieval history, and began reviewing books for learned journals. He found himself drawn to accounts of the era’s brutal jurisprudence, an interest that culminated in his first book, Superstition and Force: Essays on the Wager of Law, the Wager of Battle, the Ordeal, Torture (1866). Eight more books were to follow—a remarkable record for a writer whose career was interrupted by a decade-long hiatus in which he recovered from his worst bout of depression. Partly responsible for that withdrawal was Lea’s friend Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a Penn trustee who prescribed his vaunted rest cure—a period of near-total inactivity—to patients whose nerves failed them during the roaring Gilded Age [“The Case of S. Weir Mitchell,” Nov|Dec 2012].

Back at full speed, Lea handicapped himself by refusing to travel to Europe, where most of the archives he needed to consult were located. Instead, he bought hundreds of books and documents and had them shipped to Philadelphia; inveigled librarians into sending him precious holdings on loan; and kept copyists busy transcribing pages he couldn’t otherwise have gotten hold of. These techniques inspired UK Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli to quip, “If Mr. Lea is not stopped, all the libraries of Europe will be removed to Philadelphia.”

Kagan, professor emeritus of history at Johns Hopkins and a specialist in Spanish history, has nice things to say about the previous biography of Lea, written by Edward Sculley Bradley C1919 G1921 Gr1925 and published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 1931—but also notes some reservations. Supervised by Lea’s children, Bradley produced a book that is “far from complete,” writes Kagan, who quotes a contemporary reviewer’s description of it as a “panegyric.” With Lea and his progeny long gone, Kagan is free to contend that Lea’s claim to historical objectivity flowed from a non sequitur: time and again, he insisted that he was impartial simply because he based his conclusions on original sources.

In Kagan’s analysis, Lea was a son of the Enlightenment who could write that the Catholic Church exposed by his research exerted “an evil influence” and was “a political system adverse to the interests of humanity” without realizing that he might be painting with too broad a brush. It’s as if a more recent historian were to segue from criticizing the communist-hunting House Committee on Unamerican Activities of the 1950s as a farrago of unfairness and paranoia to dismissing the House of Representatives itself as “adverse to the interests of humanity.” One can’t help wondering if Lea’s disdain for the Church was traceable in some way to his half-Catholic heritage, but relevant evidence is apparently too meager to be of much help.

Nonetheless, Kagan speaks highly of Lea’s seminal History of the Inquisition of Spain, which points out that the Spanish branch of the Inquisition was “technically . . . a royal institution, not an ecclesiastical one” and that it thrived at a time when Spain’s rulers put a premium on religious uniformity and were rattled by “the emergence of a large, prominent class of converted Jews, conversos, suspected of secretly practicing Jewish rites.” The tragic consequences of this mindset were the expulsions of Jews from Spain in 1492 and Muslims starting in 1609.

However we come out on Lea’s judiciousness, his and his children’s generosity to Penn was lavish: an endowed chair in history; most of the books from his extensive personal library; a striking reading room to shelve them in, now on the sixth floor of the Van Pelt Library; and a fund for acquiring new books in Lea’s fields of interest. The Inquisition’s Inquisitor will make a welcome addition to the room’s holdings.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Power of Scenery: Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origin of National Parks.