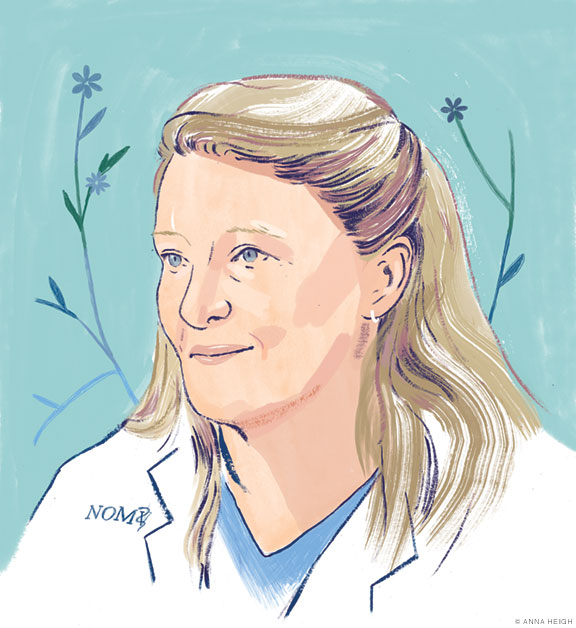

Overstressed, poorly paid, and underappreciated, veterinarians are at increased risk for depression and suicide. Support efforts are underway at peer organizations like Not One More Vet, headed by alumna Carrie Jurney, and at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

By Kathryn Levy Feldman | Illustration by Anna Heigh

Sidebar | Unpacking Euthanasia

In December 2006, a few months into her three-year residency in neurology at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine, Carrie Jurney was on call for the holidays. One of her patients, a service dog, presented with new onset seizures. The results of an MRI were medically conclusive—and devastating: an inoperable brain tumor.

“I knew what needed to be done,” recalls Jurney, who had graduated veterinary school at the University of Georgia the year before. “But the emotional turmoil of informing someone of a terminal diagnosis in their service animal during the holidays hit hard.” Making the difficult task even harder for the recently minted vet was the absence of the normal support system of those in the neurology service as well as her fellow residents.

Luckily for Jurney, Christina Bach SW’96 G’12, then the veterinary school’s social worker and currently the psychosocial content editor for PennMedicine’s online comprehensive cancer information resource OncoLink, was on site and helped her recommend euthanasia to the owner.

“As a clinician, our primary concern, of course, is for the dog and its owner, but it’s also quite stressful for the vet,” Jurney says. “Processing that grief is something you learn to do over time, and I certainly wasn’t there yet.”

Ask any vet and they will tell you about the cases that weigh heavily on their hearts. Dealing with grief and loss is an almost daily part of the profession. Add in grueling work schedules, crushing student debt coupled with low starting salaries, a demanding clientele who often challenge the cost of medical treatments and/or go elsewhere, staff shortages combined with an increase in patients due to the explosion in pet ownership since the pandemic, and you have the recipe for a profession in turmoil.

According to the first mental health survey of US veterinarians, published in March 2015 in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA), veterinarians were more likely to suffer from depression and have psychiatric disorders than the general US population. One in six had contemplated suicide since their graduation.

A 2020 AVMA report, released in partnership with Merck Animal Health, concluded that veterinarians were 2.7 times more likely than the general public to die by suicide. That figure increased to 3.5 times for women; about 10 percent of all deaths among female veterinarians from 2000 to 2015 were by suicide—an especially troubling statistic given that currently more than 60 percent of US veterinarians and 80 percent of veterinary students are women.

Technically, none of this is new to the profession. A study of California veterinarian deaths between 1960 and 1992 found that the rate of death by suicide was 2.6 times as high as that for the general public. Even the legendary veterinarian James Herriot, author of All Creatures Great and Small, is reported to have suffered bouts of depression.

Veterinary medicine has always been a field of high achievers who work extraordinarily long hours for low compensation surrounded by ethical dilemmas. What is new is the willingness of veterinarians to talk about it, thanks, in part, to an organization called Not One More Vet (NOMV), of which Jurney is currently board president. Since its founding in 2014 as a peer support network for veterinarians on Facebook, NOMV has grown to more than 30,000 members worldwide. “NOMV provides the necessary support to all members of veterinary teams and students who are struggling or considering suicide,” states the group’s website (www.nomv.org). “Because you are good enough, and you are never alone.”

Growing up in Atlanta, Jurney always knew she wanted a career in medicine and “thought for a long time it would be human medicine.” Working for a primary care physician one summer during college convinced her otherwise. “There is a joke in veterinary medicine; I even have it on a coffee mug,” she confides. “Veterinary Medicine Because People Are Gross.”

It was a subsequent job as an emergency assistant for a specialty vet in Atlanta that convinced her she had made the right choice. “I was immediately hooked,” she recalls. “I also found that I had far more empathy for a sick animal, so clearly it was the right path for me.”

Jurney graduated from Emory University with a dual concentration in neurology and behavioral biology in 2001 before heading to vet school at the University of Georgia. She says she loved “the high energy environment and complicated cases” of the ER, but watching a professor perform a brain surgery on a cat during vet school inspired her to become a neurosurgeon. Once again, she just knew.

After an internship in small animal medicine and surgery at the VCA Veterinary Specialty Center in Seattle from 2005 to 2006, Jurney was accepted to Penn for her neurology and neurosurgery residency, finishing the three-year program in 2009. “Penn was one of my top choices for a residency because of its city environment and robust critical care program” she says. “Neurology patients are often very sick, and the support of an excellent critical care department is so helpful.” Since 2015, Jurney has owned her own neurology specialty practice in the San Francisco Bay area, Jurney Veterinary Neurology.

An accomplished sculptor whose work has been exhibited at the Cathedral Gallery in Oakland, and a technology and video game enthusiast, Jurney embraces the importance of finding an outlet for the stressors of her career. “I have sculpted in almost every medium, but I currently work mostly in metal,” she says. Many of her large pieces are animal inspired. “I find my veterinary education in anatomy really helpful in sculpting,” she adds.

Jurney has been involved with NOMV since 2015, when she joined founder Nicole McArthur as its Facebook page moderator. “I was inspired to work at NOMV after a colleague of mine expressed suicidal intention while we were in surgery together,” she recalls. “Thankfully we were able to get her some help. That scary moment made every article I had ever read about burnout and compassion fatigue more real. It made me pay attention to my own well-being, and also want to help my colleagues not get to that dark place.” Jurney served as secretary of the organization prior to becoming its president in 2019 and is a founding board member. She has also participated in continuing education training in mental health and suicide prevention.

NOMV offers an online crisis support system specifically designed for veterinary professionals and also supplies support grants to help those in need out of a crisis so they can focus on their mental well-being. NOMV representatives also provide talks and workshops on a variety of topics related to veterinary mental health and well-being.

Deborah Silverstein, professor of critical care medicine at Penn Vet, has crossed paths with Jurney at professional meetings and mentored her during her Penn days. She points to a common type among veterinary students: “Just a big heart along with a very conscientious desire to excel.” Some of the field’s stressors, she suggests, are probably common to any field that includes practice in a clinical setting, but in addition to trying to “be the one to please everyone, and to always be successful in our treatment of animals as we try to diagnose, treat them, and prevent suffering,” there are the pressures students place on themselves.

“For me personally, there was a lot of internal stress of: Am I good enough? Is this sufficient? Should I be working harder?” says Greg Kaiman V’17, who finished his neurology residency in 2021. “I find that a lot of the people in the veterinary field are very self-driven people who always wonder whether or not they are good enough, a kind of imposter syndrome which is all too common in the veterinary field.”

One the one hand, being a perfectionist, as many vets are, is “the sort of skill you want in a doctor, right?” says Jurney, but the flip side is that “mistakes aren’t really acceptable when you’re a perfectionist, so that personality can absolutely play into career struggles.”

While medical students may be subject to many of these same self-doubts, the fields are “built differently,” says Kaiman. “Veterinary students are required to do a lot. They do the physical exam, they talk to the client, they do technical skills such as taking blood pressure and blood draws, and they are taking care of their inpatients at the same time,” he says.

The compensation for doctoring humans is generally much higher than for animals, so vets have fewer opportunities to earn big incomes to pay off their student loans, which are comparable to other professional degrees in medicine and law, for example. Four years of veterinary school can cost from more than $200,000 for in-state to $275,000 for out-of-state students, according to the vet education and support nonprofit VIN Foundation, while the AVMA put the average starting salary for a veterinarian in 2019 at $70,045—which translates to a possible debt-to-income ratio of about 2 to 1 for recent grads.

“Some veterinarians graduate with upwards of $400,000 of debt, between vet school and undergraduate loans. You’re making a hundred thousand dollars a year (if that) and trying to pay off your loans, buy a house, start a family,” says Kaiman. “The financial stress is massive because veterinary medicine is a profession of passion for most of us. Even with the knowledge that this is how it will be, a lot of us go into it because this is what we love, and we won’t be happy doing anything else.”

Specialists can earn more, but that means three to five more years of education, while earning $30,000 to $40,000 annually—and incurring more debt. Medical and law school students often graduate with similar levels of debt, but medical starting salaries average around $200,000 while US News and World Report put the median starting salary for lawyers at $126,930 in 2020, though going as high as $200,000.

The potential to earn more money depends on the specialty, the geographical area in which one practices, and the demand for services, but it is fair to say that there is more potential to earn higher salaries in the medical and legal professions than in the veterinary field. “No one goes into veterinary medicine to make money, and it’s not an extremely lucrative career,” says Jurney.

Along with the relative lack of compensation, some see a shortage of respect. “We are part of the healthcare system not regularly thought of as part of the healthcare system,” Jurney points out. “We have been essential workers in the pandemic since the beginning.”

Even though veterinarians undergo the same schooling and learn the same kind of medicine across multiple species, they have never been held in the same regard as their human counterparts. At the same time, clients often expect more compassion from their veterinarians than they do from their medical doctors.

“I think people expect from us something they don’t expect from physicians, which is an extra level of empathy and care for the whole situation,” muses Leontine Benedicenti, assistant professor of clinical neurology and neurosurgery and chair of the vet school’s well-being committee. “When we are talking about physicians, we just expect them to be competent and not always have good bedside manners. But because we are taking care of animals, that is always expected of us.”

One of the most stress-inducing areas of veterinary medicine is its price. Pet insurance can help, but a Liberty Mutual Insurance survey showed that three-quarters of animal owners don’t have it. That’s also true for most of the US households—nearly one in five, according to the ASPCA—that took a pet into their homes during the pandemic. The 2021–2022 national survey of pet owners by the American Pet Products Association showed pet owners estimated they spent on average $700 on dogs and $379 on cats for surgical and routine visits in the prior 12 months. But as every pet owner knows, emergencies and chronic conditions are expensive. Not having pet insurance, as Silverstein puts it, “adds on an extra layer of, ‘You’re going to put a price on my furry child’s life.’”

Despite the very real cost of care, there is the expectation “to fix an animal for free because if you loved what you did, then you would do it for free,” says Kaiman. “Or if you cared about animals, then you would give free care. I think it is a huge pressure on mental health because many of these things are out of our hands.”

“The cost of medication in the United States is not something that the individual veterinarian has much impact on. It’s a really difficult thing to navigate,” Jurney says.

And then there is the bitter fact of having to pay for care regardless of the outcome. “I can’t promise that your dog is going to make it, and you still have to pay me,” Benedicanti says.

It is not uncommon for owners to “shop around” for the best price among vets (or try to bargain) and then post the results of their comparison shopping on social media.

“We deal with people going on Facebook and saying that we are moneygrubbing animal haters,” says Jurney. “As a veterinarian to have that happen, it is very, very draining and upsetting.”

The problem goes beyond the US. Before coming to Penn, Benedicenti owned her own practice in Italy and knew two veterinarians there who ended their lives because they were cyberbullied. “When you have a small practice, that’s your life,” she says. “Suddenly, there is somebody who keeps putting stuff online about how bad you are. It becomes extremely hard.”

According to Silverstein, who has also known veterinarians in this country who have ended their lives because their practices were destroyed on social media, many vets do not have the resources to hire a person to monitor their websites and respond to or take down vitriolic comments. “People start saying things and practitioners don’t have the time to go in and try to defend themselves. It can ruin their entire livelihood in a matter of minutes.”

All of which makes the work that NOMV does more important than ever. According to Jurney, the group’s Facebook forums currently support over 35,000 veterinary professionals. “We have more than 10 percent of American veterinarians in our support forums on a day-to-day basis,” she says. “We were founded in peer support and that will always be important to us.”

At the same time, recognizing that Facebook may not be appropriate for everyone, NOMV recently launched a new program called Lifeboat where veterinary professionals can be connected completely anonymously with three of their peers who are trained in trauma-informed peer support. “Those three people are going to be there for you and talk to you in a very private environment about whatever’s happening to you and hopefully help you get through that,” says Jurney.

NOMV’s largest program is the one that provides direct resource assistance. “We’ve given out over $150,000 in direct financial assistance to veterinary professionals in the last year in the form of small grants averaging $800,” Jurney says. “Sometimes people just need real and actual help. All sorts of things can stem from a car breaking down. I can’t fix their entire life, but I can help them fix their car.”

Through its education and research department, NOMV also works to communicate the issues in the veterinary profession to the larger community. “We are scientists, and we believe that knowledge is power,” says Jurney. “By researching this problem and then disseminating the information, that’s how we make change happen.”

Back at Penn, the vet school has multiple well-being practices in place. As part of Penn’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), Heather Frost has been working as the embedded counselor to the vet school for the past four and a half years. She provides eight hours a week on site in an office at the vet school for students to meet with her for counseling sessions for one-time support or ongoing individual therapy. She offers occasional workshops on topics like stress management, mindfulness, and staying present.

“Unique to the vet field are additional struggles related to … a lack of diversity in the field (particularly in terms of race/ethnicity, gender identity, and sexuality, which can be isolating for students who hold non-majority identities,” Frost says. “I also think the vet program is particularly demanding in terms of workload and curriculum, which adds additional stress and challenge related to work-life balance.”

Former vet school social worker Christina Bach of OncoLink notes that the “first veterinary social worker was at Penn in the 1970s,” and there has been a social work presence for at least 20 years since then to help owners and staff through challenging times. Currently there are two part-time social workers at the school, one at Ryan Veterinary Hospital on campus (Jenna Tarrant) and the other at New Bolton Center (Paige Buck), as well as current social work students to assist. They offer a virtual pet loss support group for Penn Vet clients once or twice a month, counseling sessions, and seminars for students and alumni about well-being.

“Our social workers provide us with one-on-one veterinary specific care that is not available everywhere,” Silverstein points out. “The pandemic has introduced unprecedented stressors for clinicians, nurses, and support staff, and the social workers are always available for consultation to anybody and to provide resources for self-care.”

“What we know, especially for companion animals, is that these are family members. And that has evolved and has accelerated over the pandemic,” adds Buck, who has a PhD in social work and a specialization in human–animal interactions. “There are so many households now that have animals, and the pressure on the veterinarian to save this family member is tremendous.

“Many of these young professionals didn’t anticipate the extent of that piece, the human client. They’re great at taking care of animal patients, but there are manners with humans that are hard. I see that and that is not something that is ever going to go away. If anything, it is just going to intensify.”

The in-house well-being committee that Benedicenti chairs currently organizes a variety of online and in-person events for students and faculty to bring people together and offer them the opportunity to connect outside work. In addition, they recently created a dedicated recharge room in the small animal hospital that is available to anyone who needs it. A comfortable space with plants, stocked with coffee and a few treats, it offers the opportunity to step away from the stress for 20 to 30 minutes.

“It’s really something that I think was absolutely needed and is valued by everybody,” Benedicenti says. “Some people share offices, and they don’t have a space where they can actually go and be alone for a few minutes and just wind down. I think it’s very important that we were able to do this, and it’s been working well.”

More than 5,500 faculty, staff, and students across Penn Vet and other Penn schools, departments, and student life activities have participated in the ICARE program, an interactive gatekeeper training to build a caring community with the skills and resources to intervene with student stress, distress, and crisis. The vet school also offers training for anyone interested in QPR (Question, Persuade, and Refer), an evidence-based suicide prevention practice. The AVMA has waived the fee for anyone in the veterinary community to take the program.

In addition, over the last couple of years “we’ve tried to incorporate ways in the curriculum to give students a sense of how to identify potential triggers or issues within themselves or their colleagues,” Silverstein says.

According to Buck, the idea is to destigmatize mental health. “The generational shift is interesting. Most of our students talk very openly; they’ll tell you what meds they are on and what their diagnoses are,” she says. “And there’s no research that suggests that talking about suicide or even directly asking someone, ‘Hey, I am really worried about you; are you thinking of killing yourself?’ gives anyone an idea or makes their situation worse. The goal at Penn is to have the conversation openly and provide resources.”

Recently, in a full-circle moment, Silverstein reached out to Jurney to inquire about the possibility of her giving a well-being seminar to the Penn veterinary community. (There is no formal relationship between the vet school and NOMV.)

“I cannot wait for the day that my organization is no longer necessary, but unfortunately right now we’re still a very needed resource,” says Jurney.

Kathryn Levy Feldman LPS’09 writes frequently for the Gazette.

SIDEBAR

Unpacking Euthanasia

Veterinarians are unique among medical professionals in their ability to practice euthanasia. Most find it challenging but are grateful that they “are able to end their patients’ suffering,” says School of Veterinary Medicine alumna Carrie Jurney, board president of the suicide prevention and peer support group Not One More Vet. However, she acknowledges, it is “a huge subject to unpack.”

A couple of years after former vet school social worker Christina Bach SW’96 G’12 helped Jurney navigate that difficult diagnosis during the early days of her residency [see main story], the two co-taught an optional evening seminar for the vet school community on the topic of euthanasia in 2008. “We came together to talk about the euthanasia process in a way that I think a lot of people hadn’t heard about or thought about,” Bach recalls.

From the owner’s perspective, the concept of humanely ending the life of a “family member” may be uncharted territory. “Because we don’t do this in human healthcare, folks who are euthanizing their animal often have no frame of reference,” she points out. “We were really trying to help people understand the difficulty of making these decisions.”

In addition, the process itself can be very frightening. Bach remembers that “Carrie had a really wonderful way about her and how she presented euthanasia to pet owners that I think helped alleviate some of the stresses and feelings that folks had during the process and after the death of their pet.”

Bach recalls learning a lot from Jurney during their class about what happens to the animal’s body. Though she’d been through euthanasia with her own pets, “it was really the first time that I was hearing it being described in such a way that I understood more about what was happening,” she says. “Then, as the social worker, I was able to help the students be more understanding of some of the feelings and emotions that some of the pet owners were feeling.”

Each veterinarian handles the ethical and moral question of ending a life in their own way, but it’s never easy. “When I see emotions from some of the veterinarians that I work with when they are euthanizing animals, you know this isn’t easy for them either,” Bach says. “End of life care and essentially ending lives can be a daily part of their jobs, which is not something that we ever do in the humans space.”

“There is a real physical and emotional toll of euthanasia on all the parties involved and talking about it helps make the process a little easier,” seconds Jurney. —KLF

Sorry, but I graduated in 1978! I guess that I am getting old!

Fascinating and moving article! I had no clue that veterinarians faced such adversity!