In a new book, the codirector of the Penn Memory Center unravels the tapestry of Alzheimer’s science and history, and outlines the medical, social, and ethical challenges that lie ahead.

By Julia M. Klein

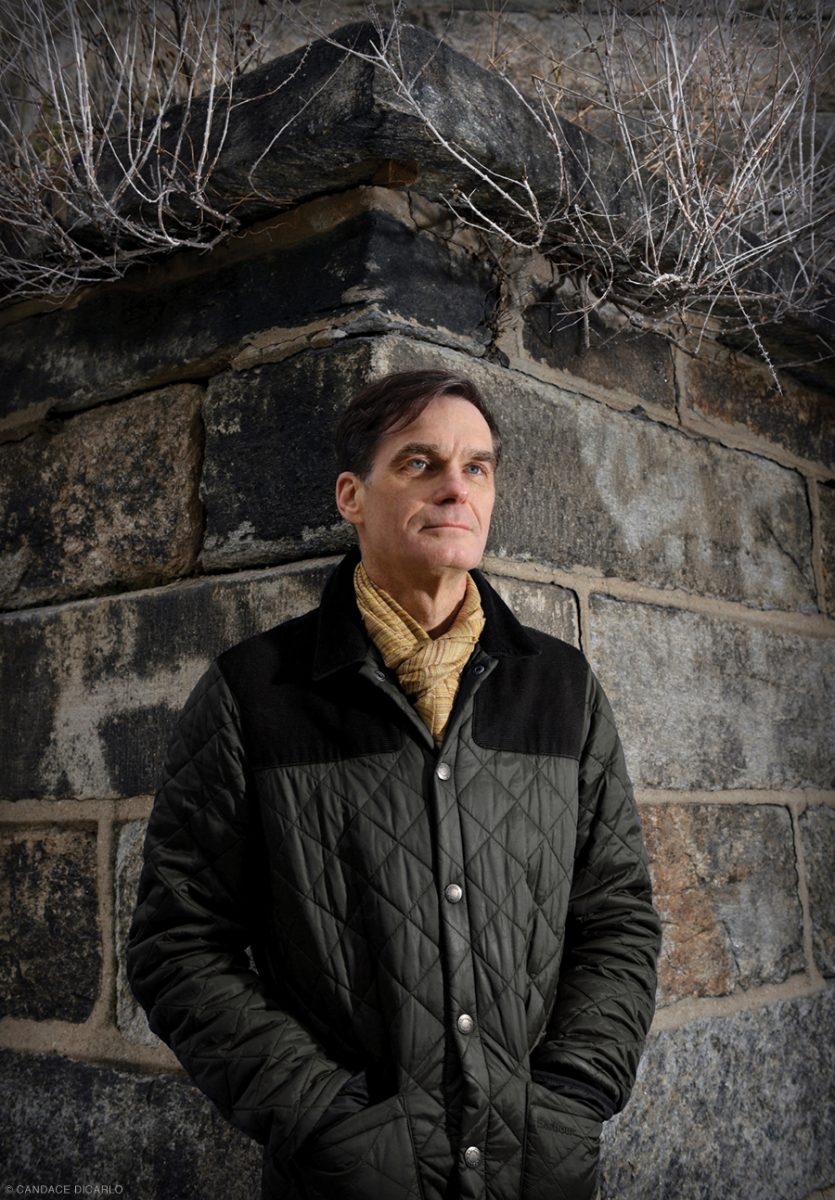

Photo by Candace diCarlo | Illustration By Gérard Dubois

When Jason Karlawish GM’99 opted in 1995 for a geriatric medicine fellowship, his friends and mentors were not just surprised. “They were aghast,” he recalls. Why was this promising young doctor, headed for a career in critical care, switching to such an unsexy specialty? At the time, geriatrics was in such low demand at the University of Chicago that Karlawish was the only fellow for three years.

That was fine with him. “They left me alone,” he says. “I did whatever I wanted”—which meant that, after taking care of patients, he spent his time in the library, poring over the geriatric literature and pondering the blurred boundaries between aging and disease. “Where does one begin, and the other end?” he wondered, asking questions that would help shape his career. “Is it a category or categories, or a continuum? Is it defined by biology? Is it defined by society? A little bit of both?”

This was hardly the first time that Karlawish, codirector of the Penn Memory Center since 2015, had flouted expectations or challenged conventional wisdom. His first post-residency fellowship was in bioethics, not yet a touchstone of medical education. He has always been as much humanist as scientist, loving history and nursing literary ambitions. As a medical student, he was a finalist in a national poetry contest for his short ode to a moth.

There was a personal reason for the switch to geriatrics: the fate of his paternal grandfather. In Karlawish’s view, modern medicine, in all its well-intentioned but misdirected zealousness, had killed the man. His 90-year-old grandfather, who had been suffering from dementia, fell and broke his hip. Hospitalized, with little attention paid to his mental state, he had spiraled down into delirium and stopped eating and drinking. Each aggressive medical intervention seemed only to worsen his condition. “It was the best of care and the worst of care,” Karlawish writes in his new book, The Problem of Alzheimer’s: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It (St. Martin’s Press). “It was a medical funhouse run by madmen.”

A nonfiction narrative filled with colorful characters, The Problem of Alzheimer’s reflects Karlawish’s multidisciplinary inclinations, ethical concerns, and passion for prose. Kirkus Reviews praises it as a “lucid, opinionated history of the science, politics, and care involved in the fight against this century’s most problematic disease,” written with a “page-turning style.”

“Jason is a really visionary thinker, and the perspectives he brings to his work are non-obvious,” says Paul Root Wolpe C’78, director of the Center for Ethics at Emory University in Atlanta and a former Penn faculty member in psychology, sociology, and medical ethics. “He’s not just another good Alzheimer’s doctor—he’s someone who sees a little further and thinks a little more deeply than a lot of his colleagues about what this disease means, how we need to think about it, how we honor the lives of people who have it.”

“He is an incredibly intense, brainy guy who just can always connect the dots,” says Christine K. Cassel, a past president and chief executive officer of the American Board of Internal Medicine who supervised Karlawish’s geriatrics fellowship at the University of Chicago.

David Wolk, an associate professor of neurology who codirects the Memory Center with Karlawish, says their interests are complementary. “Where he stops,” Karlawish says, “I pick up.” Wolk’s focus is on the neuroscience—specifically, on using cognitive testing and neuroimaging to distinguish changes related to normal aging from those signaling early Alzheimer’s disease. Wolk calls his colleague “an exquisite scholar,” whose “ability to bring historical perspective to this disease is really important because there are so many bioethical and policy implications.”

The leading cause of dementia, afflicting an estimated 5.8 million Americans, Alzheimer’s disease—or perhaps, as Karlawish’s book postulates, Alzheimer’s diseases—remains an illness without a cure and with only minimally effective treatments to slow its inexorable, devastating progression. “The more we advance in our understanding of the disease,” Karlawish says, “the more we see its complexity.”

A “weird sort of dichotomy” exists in the Alzheimer’s field, he says, between those on the hunt for a cure and those preoccupied with the economic and social crisis of caregiving. “What the book tries to do is recognize that the two simply have to live together—and do live together. The field has been haunted by pitting care versus cure,” he says. “And the book asks, ‘Why did that happen, and how can we reconcile them?’”

“I’ll show you around,” says Karlawish, volunteering a Zoom tour of his home office in the Fairmountsection of Philadelphia, near the evocative ruins of the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. He points to “a note wall, with some new ideas,” a farm-table desk bought at Freeman’s auction house, and at his feet, the elder and more sedentary of his two whippets, Sunny. The other, Daisy, with “a lot of the puppy in her,” occasionally joins them.

He shares the rowhome with his husband, John Bruza, a fellow geriatrician whom Karlawish proudly describes as “a doctor’s doctor.” The two came to Penn together in 1997 and quickly became a power geriatrics couple. Bruza is associate professor of clinical medicine and vice chief for clinical affairs in the Division of Geriatric Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine. In 2019, he won Perelman’s Sylvan Eisman Outstanding Primary Care Physician Award—the first time, according to Karlawish, that it has been awarded to a geriatrician.

Besides codirecting the Memory Center, Karlawish is professor of medicine, medical ethics and health policy, and neurology. He is a widely sought speaker on issues such as informed consent, voting rights, and financial protections for people living with dementia. Among his titles: senior fellow of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and the Penn Center for Public Health Initiatives, fellow of Penn’s Institute on Aging, director of the Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain, and co-associate director of Penn’s Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center.

Karlawish describes himself as both a physician and a writer. There is evidence of a family literary gene. Or at least Gene. Karlawish holds up a 1928 memoir, The Great Horn Spoon, by his maternal grandfather, Eugene Wright, whom he used to call “Daddy Gene.” Wright left Columbia University his junior year to become a merchant seaman, traveling to Africa and the Far East. “This book is his adventures,” Karlawish says. In 2013, an appreciative Amazon reviewer gave it five stars and praised it as a “compelling autobiographical story.”

Karlawish was born in Manhattan, the second of two brothers, and raised in the Bergen County town of Ramsey, New Jersey. His parents divorced when he was 12. “It was rough,” says Karlawish, who lived with his mother, Anne Wright, a middle school English teacher and, later, college administrator. His father, John KarlawishW’58 WG’61, worked on Wall Street as a financial analyst and investment manager. (Both are now retired.)

In 1984,Karlawish was admitted to the Honors Program in Medical Education at Northwestern University. The program enabled participants to earn a bachelor’s degree in two years before matriculating at Northwestern’s medical school in Chicago. “I knew the moment I got there that two years was not going to be enough,” Karlawish says. “I remember how excited I was looking at the course catalog at classes like the intellectual history of Europe.” With his parents’ support, he opted for an extra undergraduate year, supplementing the required premedical courses with a deep dive into history, literature, and philosophy. (The Northwestern program now mandates at least three undergraduate years.)

While he loved his liberal arts education, Karlawish says, “I had a rough time in medical school because medical school, especially then, was a trade school.” When he expressed an interest in ethics, he was told “there was not a career to be had in that space.” When he submitted an essay for his residency application about his desire to combine medicine with writing, his mentor was “so dismissive I actually had to drop him as my mentor.” Karlawish was ahead of the curve. Both the field of bioethics and the phenomenon of physician-writers—exemplars include Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), Siddhartha Mukherjee (The Emperor of All Maladies), and Atul Gawande (Being Mortal)—have become integral to contemporary medicine.

He completed an internship and residency in internal medicine—and met his future husband—in Baltimore, at the Francis Scott Key Medical Center, now part of Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. Perusing a bulletin board in a hospital lounge, he was enticed by a University of Chicago fellowship in clinical medical ethics. He was accepted to that program, and to the university’s prestigious critical care fellowship as well.

During the bioethics fellowship, he moonlighted at a chronic ventilator unit, which raised ethical conundrums of its own. “These people were alive, but chronically ill and dependent on the care of others, both human care and machine care,” he recalls. “And I became fascinated with [the question of], ‘Why did this happen to them?’”

At that point, he says, “I was interested in aging, and I was immersed in ethics.” Then his grandfather fell and entered the hospital and died. “And I just said, ‘I don’t want to go into critical care. I just don’t.’ ”

“Geriatrics is still, to this day, not a highly valued specialty in this country, much as it should be,” says Cassel, professor of medicine and senior adviser for strategy and policy at the University of California, San Francisco, and a former Penn professor of medicine and bioethics. “What stood out to me [about Karlawish] was just his intense curiosity—and intensity in general. He just doesn’t do anything halfway. He looks down unconventional hallways and opens doors that other people wouldn’t open because of that curiosity.”

Karlawish’s entry in the 1989 William Carlos Williams Poetry Contest, a national contest for medical students, was titled, To a Moth:

My room is 17 stories high,

Imagine my surprise when you came into a light

And died.

“That was it,” says Karlawish. “That was the whole poem. I probably have not written poetry since then.”

He prefers prose, the natural flow of the English language. “There’s nothing more fun than a well-constructed English sentence,” he says.

He attempted his first novel when he was about eight and has been writing ever since, including “piles of short stories.” In 1997, he won the Wakley Prize, awarded annually by the British medical journal The Lancet, for an essay titled, “A Personal Choice.”Karlawish contrasts being gay, once seen as a disease, with the “disease” of aging. Even without an identifiable illness, he writes, the aging are considered “at risk” and are subject to what he calls the risk-benefit analyses of “deskside medicine.”

Asked to reflect on parallels between his sexual orientation and an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Karlawish mentions “common themes of stigma and its many sufferings,” including the experience of being the “other,” “of feeling different and fearing rejection.” Both also give rise, he says, to the dilemma of how and when to “come out” to others.

Another link—issues of autonomy and self-determination—is a major theme of Karlawish’s research. He has done pathbreaking work on caregiving, capacity assessment, and voting rights for people living with dementia. In 2015, he introduced the concept of “whealthcare,” calling for financial institutions to identify and protect customers with cognitive impairment from fraud, missed payments, and other potential mishaps.

“Several years ago, I realized that I’m fully alive because of Alzheimer’s disease,” Karlawish says. “The triumph of self-determination for all adults has allowed me to live as I am. In the case of being gay, it’s about simply living one’s life as one determines it. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, we see how painful it is to lose that self-determination.” In both instances, he says, “caring relationships” are an important part of the equation.

Karlawish’s interest in bioethics informed his somewhat surprising and well-reviewed first book—not a scientific treatise, but an historical novel. Based closely on primary sources, Open Wound: The Tragic Obsession of Dr.William Beaumont (University of Michigan Press, 2011), tells the mostly true story of a talented and hubristic 19th-century US army surgeon who treats a French Canadian fur trapper with a near-fatal stomach wound [“Arts,” Mar|Apr 2012]. The wound heals but remains open—an opportunity, as the surgeon sees it, for the study of digestive processes. With money and other enticements, Beaumont pressures his onetime patient into submitting to sometimes painful experiments, for the advancement of both science and his own reputation.

The novel’s concerns include “the nature of what it means to be American—namely, to be ambitious, to get ahead,” Karlawish says. Reviewing Open Wound for the New York Times, Abigail Zuger, an infectious-disease specialist, described the book’s protagonist as “a true tragic hero, an unpedigreed nobody determined to succeed on his own merits, yet undermined by exactly that determination.”

Karlawish regards the novel as “part of the seamless garment of my scholarship”—and also “very much a training ground for how to really write prose.”

“Science is fragile,” says Karlawish, reflecting on the complex story he tells in The Problem of Alzheimer’s. “It’s powerful, but it’s incredibly fragile.”

The narrative weaves back and forth in time to describe how Alzheimer’s disease was discovered, forgotten, rediscovered, and elevated to a crisis. Karlawish writes about how politics and history framed, influenced, and diverted the scientific research agenda. He details recent progress in diagnosing Alzheimer’s, and the difficulties involved in prevention, treatment, and cure. And he describes moral challenges and innovations in caregiving, including the use of robots and other technology, as well as fanciful Disneyfied environments that return patients to an idealized past. The book’s recurring theme is the interplay between science and society, involving both resistance and accommodation.

Before the early 20th century, Karlawish writes, the medical profession regarded “senile dementia” as an unfortunate consequence of normal aging, to be endured rather than cured. But it was also known that middle-aged people, albeit in much smaller numbers, could develop similar symptoms, including progressive memory loss and other markers of cognitive decline.

A breakthrough came in 1906, when the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer performed a microscopic examination of the brain of a former patient, Auguste Deter. Diagnosed with dementia at 51, she was dead at 55. Alzheimer spotted abnormalities that came to be known as amyloid plaques (clumps of proteins) and tau tangles (tangles of broken protein). From 1907 to 1911, another German psychiatrist, Oskar Fischer, detected identical plaques in the brains of older dementia patients, suggesting that the pathology was the same.

These discoveries almost surely would have transformed medicine, Karlawish says, speeding progress toward a cure—had Germany’s dark 20th century history not intervened. “Had Germany not gone to war in the First World War, had there not been the social and economic collapse of the ’20s, had Nazism and anti-Semitism not destroyed the country,” he says, “it’s possible by 1940 or 1950 there would be this view that older adults who are forgetful and wandering have a disease in their brain—and we need to figure it out. But none of that happened.

“And why it didn’t happen is not because science couldn’t do it—it’s because the science was destroyed,” he says, “wrecked by 1945, caught up in the baggage of eugenics.”

As Karlawish tells the story, the early 20th-century German advances were largely forgotten. Biological psychiatry beat a retreat, and, in mid-century America, Freudianism became psychiatry’s dominant disease model and reigning ideology. In The Problem of Alzheimer’s, Karlawish recounts with some shame his own attempt, as a medical student, to apply psychodynamic theory to the diagnosis of a dementia case.

In 1976, the neurologist Robert Katzman wrote a now-legendary article that defined Alzheimer’s disease as “a major killer” and put it on the public health agenda. “A brief period of redefinition, rediscovery, reframing” followed, Karlawish says. In 1979, Katzman and others created an organization that evolved into the Alzheimer’s Association, which offers support to families and lobbies for increased federal funding.

But the country’s rightward political drift in the 1980s and early 1990s stalled progress. Bipartisan backing for federally funded long-term care insurance, a huge potential boon to Alzheimer’s patients and their families, crumbled. In November 1994, nearly six years after leaving the presidency, Ronald Reagan announced, in somewhat equivocal terms, his own Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Nevertheless, Karlawish writes: “As the twentieth century ended, the disease of the century remained a crisis without a national plan to address it.”

One of Karlawish’s arguments in The Problem of Alzheimer’s is that second-wave feminism, by expanding women’s career options, made the problem of Alzheimer’s more visible and more pressing. “One way you could address the Alzheimer’s crisis is if you created a permanent labor class of implicit caregivers whose job is to just take care of these older adults who are forgetful,” he says, referring to the prospect of women leaving the labor market to provide unpaid home care. In that case, he says, dementia would once again disappear from the public sphere, though the suffering it caused would remain.

With medicine still largely helpless, Alzheimer’s care entails an array of social, psychological, and environmental interventions that Medicare mostly won’t reimburse and that aren’t routinely available, Karlawish writes. In 2009, a report by a congressional study group estimated the annual cost of caregiving for Alzheimer’s in the United States at $100 billion. That already outdated figure will grow with the aging of the long-lived Baby Boomer population, even though healthier lifestyles have decreased the per capita prevalence of dementia.

To solve the problem of Alzheimer’s, America needs “to have an honest conversation” and “spend some money,” Karlawish says. “Never, ever underestimate how important it is in America for a disease to have a business model. And if there’s one lesson in the story of Alzheimer’s, it’s that Alzheimer’s has struggled to have a business model.”

“In a different life,” says Allison K. Hoffman, professor of law at Penn Carey Law School, Karlawish “would have been a sociologist. He’s really curious about what makes people tick and how societies operate.” She says the opportunity to collaborate with him on caregiving issues was one factor that lured her to Penn from UCLA School of Law in 2017.

In July, Hoffman and Karlawish teamed with David C. Grabowski, professor of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School, on a Washington Post opinion piece urging nursing homes to relax pandemic policies barring visitors. “Many family members are not so much company as essential caregivers and care monitors,” they wrote.

Karlawish is himself a caregiver. He has an uncle, he says, with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition that can progress to dementia. The cause is Alzheimer’s, diagnosed by clinical examination and brain imaging. By revealing the disease’s characteristic amyloid plaques, tau tangles, and neural atrophy, imaging can detect Alzheimer’s even in people whose cognitive functioning is normal.

Karlawish’s uncle has had problems with memory and executive function. He has a harder time now making decisions and performing daily activities, such as managing money. “To keep him in his home and happy, I have to nudge and integrate myself into his self. I’m intruding, just a bit, into his privacy,” Karlawish says. “I attend his physician visits. I watch over his checking account. I check in with his neighbors. I figure out what he likes, does not like, put up with his quirks and oddities. I am beholding how the lives of the caregiver and patient become enmeshed.”

Karlawish stresses that he has assumed these tasks with his uncle’s permission—and only after talking to him openly about his diagnosis, which provides them with “a common language, a common understanding.”

There are drugs, Karlawish says, that can treat the disease’s symptoms, but none so far able to attack the pathology. One modest hopeful sign: in January, Eli Lilly announced positive preliminary results in a small Phase II trial for donanemab, which targets amyloid plaques. The drug cleared the plaques and slowed the rate of cognitive and functional decline by about a third compared to placebo.

One of the problems in finding a cure, Karlawish says, is the “heterogeneity” of the disease, which can have different neurological and behavioral manifestations. It might be helpful, he suggests, to think about Alzheimer’s diseases, plural. And, as with different forms of cancer, some types of Alzheimer’s may turn out to be more treatable than others, he says.

Meanwhile, supported in part by the National Institute on Aging, facilities such as the Memory Center diagnose, monitor disease progress, and offer activities for both patients and caregivers. The center runs classes, workshops, and support groups for caregivers. It sponsors innovative events such as Cognitive Comedy, Creative Expression Through Music, and a monthly Memory Café, featuring dance, music, talks, zoo animals, and more—all held virtually during the pandemic.

When Renee Packel first called the Memory Center, more than two decades ago, she was desperate to find a geriatrician to see her husband, Arthur, a lawyer in his late 60s who was struggling at work and having trouble driving familiar routes. “I’ll take anybody,” she said.

Eight months passed before she could secure an appointment. It turned out to be with Karlawish. “It was the luckiest break ever,” she says, “because that man is something else. He’s so compassionate, so caring. He treats his patients with dignity. He never called Art anything other than Mr. Packel.”

Karlawish introduced Renee Packel to the concept of “loving deceptions.” She recalls: “He said, ‘Always be in their moment. If he looks outside, and the sun is shining, and he says it’s dark, you say it’s dark.’” At one point, her husband started hallucinating that there were men in the bathroom. She remembers responding: “Oh, yeah—I have them working. They’ll leave soon.”

Another time, he mistook her for his brother Morton. “I said, ‘I’m not Mortie—I’m your wife.’ He looked at me and burst out laughing. You have to laugh along with it. Otherwise, you would go crazy.”

Packel’s life was convulsed by her husband’s illness. As she recounted in a 2010 New York Times article, her husband had stopped paying their bills. Worse, even with the aid of a forensic accountant, she was unable to locate their nest egg. The money seemed to be gone. She ended up having to sell their house and take a job, at 75, as a receptionist.

At Karlawish’s suggestion, Packel sent her husband to adult day care. But as he grew more ill and experienced falls, the physical challenges of keeping him at home proved overwhelming. Reluctantly, she institutionalized him. But that, too, entailed challenges. He became so “rambunctious” and “disruptive,” she says, that the nursing home sedated him to the point where he nearly stopped eating and drinking. She insisted that the medication be halted. In The Problem of Alzheimer’s, Karlawish describes her anguish over that decision, which likely prolonged her husband’s life. “I have no regrets,” she says now. “I did what I did, and that was it. It was the right thing in the long run.”

Many caregivers experience profound emotional conflict around such dilemmas, Karlawish says. Like concentration camp inmates and others who endure “sustained traumas,” they wrestle with the cost-benefit calculus of survival, suffering, and encroaching mortality.

In his acknowledgments, Karlawish credits Packel, who sometimes talks to his class on Alzheimer’s disease, as one of the inspirations for his book. Another is Richard W. Bartholomew C’63 GAr’65, a retired architect and urban planner who taught in Penn’s Department of Architecture and Urban Design. Bartholomew’s wife, Julia Moore Converse, who had early-onset Alzheimer’s and died in May [“Obituaries,” Sep|Oct 2020], was founding director of Penn’s Architectural Archives and an assistant dean for external relations at what is now the Stuart A. Weitzman School of Design. Her father and uncle were both US ambassadors to Ireland.

Bartholomew, like Packel, has spoken to Karlawish’s students about his struggles as a caregiver, about which he kept a meticulous journal. “One of the problems with almost every Alzheimer’s patient is boredom,” Bartholomew says. When Converse stopped reading, he found himself “constantly looking for activities to engage her.” Penn’s Memory Café was one solution; another was a Philadelphia art appreciation program for people living with dementia called ARTZ at the Museum, perfect for someone with Converse’s curatorial background.

Karlawish urged Bartholomew to find caregiving assistance, which he did, by trial and error and serendipity. The doctor also suggested adult day care, but Converse resisted. When she required colon cancer surgery, Karlawish advised Bartholomew to enlist family members to stay with her in shifts to avoid the problem of delirium that had afflicted his grandfather. Even as the pandemic narrowed their world, Bartholomew was able to take care of his wife at home. And Karlawish helped him figure out the right moment to turn to Medicare-financed hospice care to ease her final weeks. “At one point,” Bartholomew recalls, “he said to me, ‘Ms. Converse and you have been among my best teachers.’”

From 2016 to 2018, retired Philadelphia Inquirer sports columnist Bill Lyon chronicled his battle with Alzheimer’s disease in a series of Inquirer articles that candidly mapped both his decline and his determination to resist it.

“He’s a hero,” says Karlawish of Lyon, who died in 2019, at 81. Karlawish was his physician and wrote companion pieces to the series. “The inspiration of Bill Lyon is that he looked the stigma of Alzheimer’s in the face and just batted it away like a fly.”

Elsewhere, though, the stigma remains.

One of Karlawish’s current research projects involves trying “to understand how persons with advanced dementia communicate with their family members.” Among the questions he is asking: How do other people perceive those with advanced dementia? How do their perceptions influence the decisions they make about their care?

Another project studies the impact of biomarker-based diagnosis. Brain imaging can detect signs of Alzheimer’s before any disability emerges. But diagnosis carries ethical risk. “The disease is so crushing that the decision to come forth and tell people you have it is truly monumental,” Karlawish says. “Even amongst my patients, they resist telling their own family members. They fear being treated differently. They fear that any mistake will be exaggerated, that they’ll be excluded from doing things.

“I don’t have a fundamental problem with diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease before one has a memory problem,” he says. “My objection is the world in which those diagnoses are made. My objection is labeling some with Alzheimer’s, and then finding they suffer crushing stigmas and discrimination that make them feel less than capable and worthy.

“Right now,” he says, “the benefit is purely information,” an aid to planning. “For some, that’s very empowering. You could make a good case [for early diagnosis] out of respect for their autonomy and self-determination.”

But testing is expensive. “You start to get into some rough economic issues,” questions about resource allocation, he says—until the time when those diagnosed have a realistic chance of avoiding the disease’s dire consequences.

“Once you introduce a treatment that you think slows the natural history, you change that economic equation substantially,” Karlawish says, “because you have a chance of helping not just to predict, but also to prevent disability or reduce the likelihood of it. One of my missions, though, is to ensure that the society within which that happens is culturally and ethically and socially prepared. And I don’t think right now we are.”

Julia M. Klein, a frequent Gazette contributor, has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Mother Jones, Slate, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.