Andrew Feiler documents the Rosenwald schools, which educated hundreds of thousands of African Americans in the Jim Crow South.

By JoAnn Greco | Photography by Andrew Feiler

“It’s a story that touches every pillar of my life,” says Andrew Feiler W’84. “I am Jewish, I am Southern, I am progressive. So, how could I never have heard of it?”

The Atlanta-based photographer is referring to the history he explores in his latest book, A Better Life for Their Children (University of Georgia Press). The result of a three-and-a-half-year quest that took Feiler to 15 states, the book surveys a small fraction of the 4,977 schools built between 1912 and 1932 (one more school was added in 1937) for Black students across the South. Known as Rosenwald schools, they were the product of a unique partnership between Julius Rosenwald, the Jewish president of Sears Roebuck, and Booker T. Washington, the prominent Black educator.

The program’s hundreds of thousands of graduates included luminaries like activist Medgar Evers, poet Maya Angelou, and Congressman John Lewis, whose preface touches upon his experience at the Dunn’s Chapel School in rural Alabama. “I loved school, loved everything about it, no matter how good or bad I was at it,” he writes. “I loved reading … [B]iographies were my favorite, stories that opened my eyes to the world beyond.”

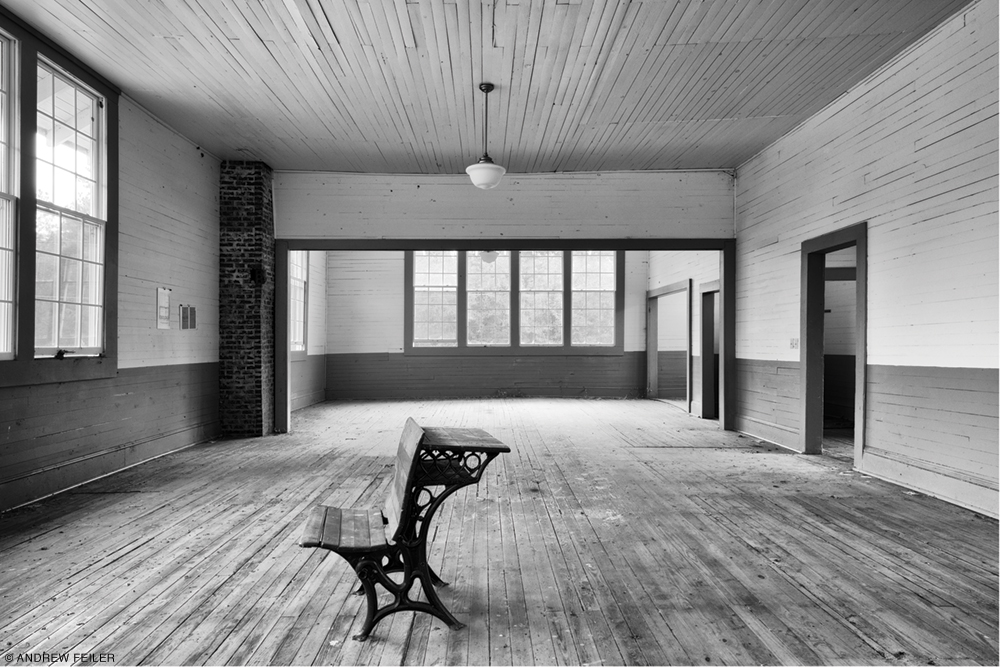

Lewis remembers his school as a “small wooden building, whitewashed and with large windows” illuminating an interior partitioned into two rooms and warmed by cast iron stoves. These elements—along with brick chimneys, wide-plank heart pine floors, and separate cloakrooms—show up again and again in the pages that follow, beginning with the Emory School. The oldest surviving Rosenwald school, it served Black students in Hale County, Alabama, from 1915 through 1962. (School closing dates vary depending on state responses to the 1954 and 1955 Supreme Court decisions requiring desegregation of public schools.) In his text, Feiler posits that Emory represents a distillation of the principles and designs—developed by Robert Robinson Taylor, the nation’s first accredited African American architect—that governed the early schools. Drawing from dozens of books and articles, National Trust applications, and his interviews with former students, teachers, preservationists, and historians, Feiler expertly enhances each photo with information illustrating significant elements in the design, expansion or financing of the program or to place the buildings in a larger context.

“Every school has a story,” he says.

The Jefferson Jacob School in Kentucky, an early example of a multilevel school building, has the expansive feel of a gracious residence, thanks to its white clapboard, pitched roof, and the ornamental flourish of a bell tower. “Such architectural niceties were discouraged by the officials overseeing the program,” Feiler writes. “[It] illustrates the degree to which local communities exercised design flexibility in the early years of the program.” In stark contrast is Rosenwald Hall in Oklahoma: an unadorned brick structure that squats solemnly in a forsaken landscape. Feiler traces its history to the slaves who accompanied Native Americans westward on forced migrations from the South during the 1830s and 1840s. Once emancipated, these African Americans went on to create more than 50 all-Black towns in the Sooner State; this school is one of at least 11 that opened in those towns.

“In recent years, I’ve been drawn to using my voice as a photographer for a broader understanding of the role that education has played as an on-ramp to the American middle class,” Feiler says. It’s especially apt, then, that photography played a role in the program’s early development, he adds. “When Washington sent photographs of students and teachers assembled in front of the six pilot schools in Alabama, Rosenwald was so moved by the images that he committed to expanding the program.”

Feiler pays homage to those historical photographs in his own visual language, which echoes their black-and-white tones and horizontal orientation.

“I started out photographing exteriors, then added interiors, but ultimately I realized that it was the people that enlivened the buildings,” Feiler says. “So many of the Rosenwald students went on to become educators and then got involved in preserving the schools. They are keepers of a flame that testifies to the importance of education.” Take Sophia and Elroy Williams, whom Feiler photographed at the Hopewell School outside of Austin, Texas, holding a gilded portrait of Sophia’s grandparents. Feiler’s narrative unspools the threads of their story. Born into slavery, Sophia’s grandparents married in 1874; decades later her grandmother donated land to the county for a Rosenwald school. Their daughter (Sophia’s mother) was the school’s first teacher, and Sophia, a former Hopewell student herself, also became a teacher in the county. So did Elroy, who attended a different Rosenwald school in the region. Over the years, Elroy has dedicated himself to the restoration of Hopewell, putting together grant applications and even personally shoring up the building’s roof at one point. The hope is to one day convert the former school into a community center.

As Feiler discovered, every minute counts in efforts to save the 500 or so extant schools. “I really wanted to visit the W. E. B. Du Bois School in North Carolina,” he recalls. “It had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places for years, but when I arrived, I was distraught to find yellow caution tape around a pile of rubble.” The school had been deemed a hazard and demolished a few days before Feiler got there. His documentation of the scene serves as a silent commentary, a cautionary tale that tempers the book’s hopeful tone. But, its author insists, the overall narrative remains a positive one, exemplified by many of the schools’ continued lives as daycare centers and apartments, as small museums and church halls. “The ultimate story here,” he says, “is that from Rosenwald himself to the people who are part of the momentum, individual action can make a difference.”

An exhibition of selected prints from the book is due to open this April at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta; plans call for it to travel to other venues, including the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience in New Orleans, the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, and the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond.