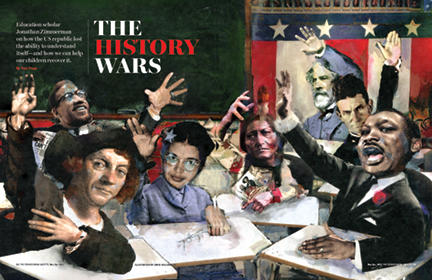

Education scholar Jonathan Zimmerman on how the US republic lost the ability to understand itself—and how we can help our children recover it.

By Trey Popp | Illustration by David Hollenbach

“There’s no other way to interpret our moment other than as an epic failure of education.”

It’s the middle of November, and education historian Jonathan Zimmerman is not in the mood to steer conversation toward his latest book. The Amateur Hour: A History of College Teaching in America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020) is his eighth. The title’s final word—America—furnishes the link to all the others. From a history of one-room schoolhouses, to separate histories of alcohol and sex education, to an exploration of US campus politics, to a history of American teachers abroad, Zimmerman’s bibliography is above all else an examination of the US republic. And in the bile-spattered, venom-splashed, conspiracy-stained wake of the 2020 election, he laments the state of the union.

“It’s not the ‘fault’ of teachers,” he continues—dispatching with the customary scapegoat of much education-reform discourse (and one that has its own lengthy history). “I’m talking about education writ large.” Which has failed, he contends, on two fronts.

“First of all, we haven’t taught people how to discriminate between information and disinformation.”

That ability, and the discipline to exercise it, “is at the heart of all intellectual activity—and it’s at the heart of democracy,” says Zimmerman, who is the Judy and Howard Berkowitz Professor in Education in Penn’s Graduate School of Education. For instance, “You have to be able to discriminate between ‘vaccines keep you safe’ or ‘vaccines give you autism.’

“And it’s not just a Democratic/Republican thing—it really isn’t,” he adds. For that’s another Zimmerman hallmark: yanking the rug out from under self-satisfied liberals. “How many people are there in Boulder, Colorado, who scoff—appropriately in my view—at climate change denial, yet who don’t vaccinate their kids? A lot, and they’re all Democrats, virtually every single one,” he says, slipping momentarily into hyperbole. (State-level legislation to expand personal exemptions to childhood vaccinations has been a bipartisan affair over the last decade, though a 2018 study found that Republican legislators have sponsored more such bills; another study, in California, found significantly higher rates of non-vaccination in heavily Republican neighborhoods than in heavily Democratic ones.)

“So there is a war on science, there is a war on expertise, there is this inability to discriminate—but I think it’s a slur to call it Republican,” Zimmerman goes on. “It’s true that there are more Republican climate change denialists than Democrats—but there are sizeable numbers of Democrats. And same for the anti-vax thing: there’s a skew, but it’s not one or another. So it’s a failure that we haven’t taught people these basic skills.

“Obviously there are efforts to do this—it’s not that we don’t teach it,” he allows. “But we don’t teach it well enough. There’s no other way to interpret all this. If millions of people think that in Congress there is a conspiracy of people that are sexually abusing children and drinking their blood,” he says, referring to QAnon adherents, “and if we just elected somebody to that body who seems to believe that—well, we’ve got a problem with our education system.”

The second failure clasps hands with the first: “We haven’t taught people to engage across their differences. And to me that’s also an educational problem.” To the extent that contemporary Americans are taught the practice of political discourse, they learn it largely from cable news, whose model for debate amounts to four faces appearing on a screen and yelling at each other. “That’s what we’ve socialized people to think politics is,” Zimmerman says.

“And the only institution that has even a chance of intervening in that,” he contends, “is a school.”

Photo by Tommy Leonardi

Historians of education are rare enough that it would be odd to suggest that anyone might be destined to become one, but there’s little doubt that Zimmerman’s academic interest in academics stems from a peculiar fact of his childhood: he attended an Anglican school for girls.

Bishop Cotton Girls’ School was located in Bangalore, India, to which Jonathan’s parents had been posted as Peace Corps administrators in the late 1960s. It was an Anglophone institution in a neighborhood near their home, and every year it took a handful of boys, so that was that.

“When you’re that young, you don’t know how weird the stuff you’re doing is. Kids never do—they just do it!” Zimmerman says now. Bishop Cotton’s pedagogical style was “what you might guess of an Anglican school in South India during the Cold War,” he says. “There was a lot of memorization, a lot of copying. But there was rigor to all that as well, which I’m glad I received. Those nuns, when I goofed off—which I did a lot because I was getting so much attention—they’d give me a little rap to the knuckles with the ruler.

“And I’m not saying I support that, or that I would do that,” he interjects, “but I am not the worse for wear. There are so many ways to skin a cat when it comes to schooling, and I think that what my own experience did was sensitize me to that variety.”

When the Peace Corps shifted his parents to Iran, Jonathan got a whole different kind of education, at an international school in Tehran. It was the height of the oil boom, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was on a quest for superpower status, and petrol money had turned the capital into a cosmopolitan crossroads. “The term international school is often a misnomer, but in this case it really was that: a quarter Persian, a quarter American, and half everyone else,” Zimmerman remembers. “I had friends from Poland, South Africa, the UK … because Tehran was going to be the Paris of the Middle East.

“It was an amazing experience,” he says, “and it was a great place to be an American.” Not just because of petrodollars and geopolitics, but because Iranians seemed so fascinated by and favorably disposed toward the United States. Zimmerman vividly remembers watching the iconic first fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier with his parents’ cook, who was transfixed by the spectacle of two Black Americans, one bearing an Islamic name, clashing in a bout that guaranteed them equal shares of a $5 million purse.

“I was also there for the moon landing,” Zimmerman reminisces, “which was a huge moment of American pride.”

Zimmerman calls his elementary-school education in Bangalore and Tehran the most formative experience of his life (apart from, years later, meeting his wife). “Together with my own Peace Corps experience as a teacher in Nepal, it made me interested in the way different communities around the world try to reproduce themselves via schools, and try to make citizens. Because that’s what schools in every place do. And they do it in all kinds of different ways. It’s deeply inflected by culture, religion, and often race. It made me more interested in that variety, and more tolerant of it—and more skeptical of whatever bromides we’re offering in the current moment.”

In point of fact, the aftermath of the 2020 election was rough going for bromide peddlers—about education or any other aspect of civic life in America. Indeed, as widespread rejection of the election’s legitimacy among Republicans bloomed into chatter about “secession” in some quarters of right-wing media and the Texas GOP (before exploding into the deadly insurrection on Capitol Hill on January 6), it took considerable grammatical strain to speak of America in the singular case at all.

“One thing that everyone said, no matter where they were, is, ‘God, I didn’t know there were that many people on the other side,’” Zimmerman remarks about reactions to the presidential vote totals. “Wasn’t that remarkable! Myself and my Biden friends are like, ‘Holy shit, 71 million people on the other side?! Who are these people?’ But you go to Trump Land, and they say exactly the same thing. They live in their own bubble, and that bubble has persuaded them they are in the majority, and they’re like, ‘74 million people for Biden? Who are these people?’” (When the count was finished, those totals would rise to roughly 74 million for Donald Trump W’68 and 81 million for President Joe Biden Hon’13.)

“We have radically different understandings of America right now,” he goes on. “But that’s not the problem. The problem is we don’t actually have venues and institutions to deliberate those differences. That’s what this last election was about. And our educational institutions have not stepped into that challenge. They are critical here. They are our key institutions, and public ones, to discuss and deliberate what we want to communicate to our young—and even to discuss and deliberate who we are.”

Who Americans are is bound up tightly in who we have been, how that has changed, and how each generation has connected itself to the story of those who came before—shifting the narrative’s arcs and emphases with every extension. Who we are, in other words, is a matter of our history.

Which is why the book on Zimmerman’s mind was neither his latest nor his next (a paean to free speech, largely aimed at campus liberals who’ve grown skeptical of it), but one of his first: a 2002 volume examining the history of how American schools have taught US history. Whose America?: Culture Wars in the Public Schools (Harvard University Press) plumbed themes that proved resonant in 2020, and not just around the election. During a summer when social justice activists campaigned to eliminate public memorials to figures they associated with white supremacy, Zimmerman repeatedly drew from that book in newspaper op-ed columns to push back against attempts to cashier Christopher Columbus, for example, or to bury memorials to Confederate insurrectionists in deep storage. (He did so while simultaneously pushing back against the notion that the latter are anything but the “racist memorials” they have in fact been since their installation, by the so-called Redeemers who restored white supremacy after Reconstruction. Zimmerman, suffice it say, does a lot of pushing back.)

Statues may be a uniquely reductive form of commemorating the past, but the history of Columbus busts reveals a deeper insight about the way Americans have gone about distilling the vast past into digestible textbook form. As Zimmerman argued this summer, the key to understanding Columbus statues in the US lies in the timing of their proliferation. They did not begin appearing until well after the Civil War, and the vast majority date to the turn of the 20th century. If there was a watershed year in Columbus veneration, it was probably 1892, when the first statues went up in New York and Chicago, among other US cities. That year was the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage to the Caribbean. (The Genoan explorer never made landfall in North America.) But that milestone may well have gone unmarked if not for a more proximate catalyst: the poor treatment of Italian immigrants who had arrived in large numbers over the preceding decades. The nadir of anti-Italian discrimination in the US arguably came in 1891, when a white mob in New Orleans lynched 11 Sicilian immigrants in a vigilante action that future president Theodore Roosevelt deemed “rather a good thing.”

Eager to establish themselves as part of the American community in the face of pervasive intolerance, Italian immigrants set out to elevate a historical figure who could support their claim to civic belonging. “Columbus statues arose during the same years” that Confederate memorials began appearing amidst the reestablishment of apartheid regimes in the post-Reconstruction South, Zimmerman writes, “but they aimed to rebut white racism rather than to further it. And the bigotry they targeted wasn’t against blacks, but against another despised minority group: Italians.”

What began with fundraising drives for memorial statues would gradually morph into campaigns directed at history textbooks. The goal was to ensure that the American story didn’t simply begin with the Mayflower landing in 1620, but with Columbus’s trans-Atlantic voyages more than a century before. And the success of that framing effort would set an enduring template for the curation of American history.

The drive to place the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María on par with the Mayflower was by no means an act of historical invention. Columbus had been recognized by earlier generations of Americans—otherwise it wouldn’t have worked. (In the 18th and early 19th centuries, however, it was more common to encounter the figure of Columbia, a poetic feminine personification that melded the explorer’s name with a Latin suffix and neoclassical imagery to create a broadly symbolic representation of America.) Elevating the Columbus story was instead an act of historical emphasis. And it would be neither the first nor the last. The explorer’s legacy had enjoyed an earlier promotion, so to speak, after the American Revolution—when citizens of the new republic wanted heroes who weren’t British. But that pendulum would continue to swing.

In Whose America, Zimmerman documents the striking malleability of the Revolution’s portrayal by history textbooks in the early 20th century. Even successive editions of the same book—David S. Muzzey’s An American History—featured remarkable shifts in emphasis; what in 1911 was presented as a complex dispute involving pro- and anti-royalist factions on both sides of the Atlantic, had by 1925 been revised into “a simplistic statement of British malfeasance and American resistance.” In the middle of that stretch, other major authors altered their own texts to reinforce pro-British sentiments—an editorial choice shaped by the exigencies of World War I. “There is nothing I would not do to bring about the warmest relations between the English-speaking peoples,” Zimmerman quotes the historian Claude Van Tyne stating in 1918. “To my mind the whole future of the democratic world depends upon that factor.” That imperative coincided with a fresh emphasis on socioeconomic analysis that served partially to highlight British contributions to America’s development. As a historical methodology, this approach was perfectly justifiable in purely scholarly terms—but Zimmerman contends that historians of the era were also cognizant of its potential influence on contemporary affairs. “By complicating the old story of a venomous England and a virtuous America, scholars believed, the ‘new’ history would help heal old wounds between them.”

In due course this ‘new history’ would arouse the ire of right-wing groups who felt that the trend toward socioeconomic analysis came at the expense of the Founding Fathers and other Anglo-Saxon patriots. As such groups lobbied state legislatures to ban “treasonous textbooks” in the 1920s, they got a surprising ally. As Zimmerman puts it, hyphenated Americans and “nonwhite activists also joined the assault.” Much like the Italian Americans who wanted to preserve a place for Columbus, these ethnic groups were fine with celebrating the Anglo-Saxon pantheon—as long as their own heroes got at least cameo roles. German Americans (especially after World War I) lobbied for the inclusion of Daniel Pastorius and the settlers in Germantown, Pennsylvania, who produced the first anti-slavery petition on American soil. American Indians stumped for figures like Pocahontas and Tecumseh. Polish Americans wrangled with Lithuanian Americans over who had the rightful claim to Casimir Pulaski, the Revolutionary War hero popularly known as “the father of the American cavalry.” Norwegian Americans would soon joust with their Italian counterparts over who really discovered the Americas: Columbus or Leif Erikson. “Even as they condemned ‘pro-British’ textbooks,” Zimmerman showed, “ethnic groups often competed with one another to revise them.”

As such efforts gained traction, one group remained essentially outcaste in the nation’s history texts: African Americans. The simple truth was that neither the Italians nor the Irish nor any other immigrant group confronted bigotry on the scale of that which afflicted Black citizens, especially during Jim Crow. And the sectional battle over Civil War historiography posed a towering obstacle. In 1895, 32 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, veterans in Richmond, Virginia, complained about a text that depicted it as “patriotic and proper” rather than as a “palpable violation of the Constitution.” Yet such objections were less a last gasp than a template that would extend well into the second half of the 20th century.

As Zimmerman documents in Whose America, a powerful campaign helmed by Mildred Lewis Rutherford, the historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy whose textbook activism lasted until her death in 1928, effectively imposed an ultimatum on the five things American history texts must not do: define the war as a “rebellion”; call any Confederate soldier a “traitor or rebel”; “say that the South fought to hold her slaves”; “glorify Lincoln”; or impugn a slaveholder as “unjust to his slaves.” (In Rutherford’s stated opinion, “slaves were the happiest people on the face of the globe, free from care or thought of food, clothes, home.”)

By and large, publishers responded as they had to their ethnic critics: by catering to their sensitivities—but almost exclusively to the sensitivities of whites. “The most common pattern of southern textbook development,” Zimmerman writes, was that “Confederate groups complained about a text, then the publisher altered it.”

Some publishers released separate Southern or state-specific editions. Others bowdlerized texts marketed nationwide. Neo-Confederate activists won capitulations ranging from soft-pedaled depictions of slavery, to the excision of words like “rebellion” to describe the conflict, to picayune matters like expunging a mathematics word problem asking pupils to calculate Ulysses S. Grant’s age on the day the Union general captured Vicksburg. “Other Confederate groups,” Zimmerman observed, “bragged that they had successfully pressured publishers to discard or replace entire chapters, including one textbook’s discussion of the causes of the Civil War.”

In one of the many instances of strange bedfellows that have cropped up in America’s history-textbook wars, in the 1920s “southern loyalists joined with their erstwhile Yankee enemies to stop—or at least slow—the entry of ‘new’ history into American schools,” fearing that “too much concern with impersonal ‘causes’ and ‘forces’ would sap children’s faith in their forefathers.”

Yet a decade later, the same critics began invoking the “new” history—embracing the class-based analysis by which historians Charles and Mary Beard reinterpreted the Civil War as an essentially economic clash while “minimiz[ing] its moral dimensions, particular those surrounding slavery.”

As the 1930s gave way to the ’40s and ’50s, “anti-black errors and stereotypes continued to mar nearly every American history text,” Zimmerman writes, especially in the form of “exaggerated accounts of black violence, incompetence, and corruption during Reconstruction.”

Led by figures including W. E. B. DuBois and Carter G. Woodson, African American scholars “struggled valiantly to repel racist interpretations, winning special courses in some schools and slightly revised general history textbooks in others. But they could not overcome American’s united front of white opinion, which sought to placate—if not always to satisfy—southern concerns. … Not until the 1960s would black Americans rise up en masse against racist history, compelling the rest of the country to take heed.”

By the 1990s, as Zimmerman summarizes, a “classic American bargain” had emerged in history textbooks’ discussions of race and religion. Equally amenable to the varied groups and the publishers who aimed to please them, it boiled down to: You get your heroes, I get mine.

“We have radically diversified the story,” Zimmerman says. “Anyone who says, for example, that high school American history now is only about white men, they just haven’t looked at a textbook. If you looked at a textbook 60 years ago, you would have been right. But you look at it now—the 800 pages that middle school kids carry around—and it’s a great rainbow. If you want something about Kazakh Americans, there’s a sidebar about the great things they’ve done.”

As a way for marginalized groups to gain acceptance in a society that has disdained them, this has in some cases been phenomenally effective. (Just how effective is evident in the very fact that statues of Christopher Columbus were targeted by opponents of white supremacy this past summer. “Never mind that Columbus himself wouldn’t have been recognized as fully white if he walked down the streets of New York in 1892, when the grand monument in Columbus Circle went up,” Zimmerman wrote in June. “Italians are white now, and so is Columbus.” That’s why in 2020 he was regarded not as “the bold discoverer from Genoa,” but instead as a violent tyrant who enslaved more than a thousand inhabitants of the land he claimed for the Spanish monarchy, and hence is “saddled with the sins of a race that long rejected people like him.”)

But as a way to understand the past, this “bargain” has considerable downsides. For one thing, the focus on inclusion has an unstated corollary that applies to virtually all hero worship: the urge to bend their records into alignment with one or another set of present-day ideals, and a bias toward glossing over anything unsavory.

“Since the 1920s each group that has gained admission to the grand national narrative has received the same fulsome praise as the nation itself,” Zimmerman writes. “True, groups that were excluded from this story—especially African Americans—were often horribly denigrated or stigmatized. Once they earned a place in the pantheon, however, they became as sacrosanct as any other god. For instance, today’s texts shy away from discussing the African role in the slave trade or the human sacrifice practiced by some Native Americans prior to the European conquest. These facts would temper the texts’ image of minority groups as uniformly peaceful and morally pristine.”

Zimmerman learned just how restrictive that can be during an early-career stint as a sixth-grade social studies teacher in Baltimore. During a unit on the civil rights movement, a student asked him if it was true that Martin Luther King, Jr., had engaged in extramarital affairs. Zimmerman did what he thought any good progressive educator should do. He planned a lesson around it.

“I came in the next day, brought up the question, and I said, ‘The answer is yes, but that’s not exactly what we’re going to talk about. We are trying to become historians here—so what we’re going to try to figure out is: How do we know the answer is yes?”

And how we know, he went on, is that in 1963 US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy authorized the FBI to wiretap King’s telephones, which it did for the next three years, obtaining recordings with which the Bureau attempted to blackmail the civil rights advocate. “I laid this out for my class,” Zimmerman remembers. “And one of the kids, an African American, raises his hand and says, ‘So you’re saying he was an enemy of the state!’ And I said, ‘Yes, I think you are right. I think that is what I’m saying. If the state goes through all that sound and fury to try to destroy you, I think you’re an enemy of the state.’

“Now it’s all been so sanitized,” Zimmerman says, slipping into a kindergarten cadence: “Happy Birthday, Martin! Day of Service! I think people have lost sight of the history, which is that he was the most dangerous American—the person who was scariest to the state.” (Two days after King’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech, the FBI’s head of domestic intelligence issued a memo declaring, “We must mark him now as the most dangerous Negro in the future of this nation.” Despite King’s working relationship with Lyndon Johnson, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover led a dogged campaign against King, whose public acclaim gradually shrank to the point that 75 percent of whites and 48 percent of Blacks disapproved of him in a Harris poll two months before his death in 1968.)

When the class period ended, Zimmerman walked out thinking, Wow, that kind of worked! Then the phone calls began coming into the principal.

Those led to a charged meeting between Zimmerman and some classroom parents. “Their take was pretty simple,” he remembers. “They said: ‘Look, you’re a white guy, you already have heroes. There are plenty of them. They’re on the fucking money: Washington, Lincoln, Hamilton, Jackson, Franklin. We have this one guy, and you don’t like him. You can’t accept him, so you want to degrade and diminish him in front of our kids, who have in the pantheon of their heroes only this one guy.’

“I did my best to respond, but I don’t think I did it very well,” he says now. “But reflecting on that episode, it highlights just how difficult it is to have a conversation about who we are. And I don’t begrudge those parents for objecting. They’re citizens, they’re taxpayers, they’re parents, and they have every right to object. I didn’t agree with the thrust of their objection—and I certainly can confirm that I was certainly not trying to turn their kids against Martin Luther King.

“But I can imagine why some of them might have thought so,” he continues. “And when you blow that out in any direction, you can just imagine the number of people who would say, You’re trying to turn my kids against X. ‘You just told my kids about Abu Ghraib—how are they going to respect the military? Their dad’s a vet; are they going to respect their dad?’ I could give you a hundred examples.”

The upshot is that a “lazy multiculturalism” becomes the path of least resistance for teaching US history: “just add the Kazakh Americans and it will be all fine,” as Zimmerman quips.

This basic critique dates back at least to 1979, when journalist and historian Frances FitzGerald observed that “the principle that lies behind textbook history is that the inclusion of nasty information constitutes bias even if the information is true.” Ditto for the inclusion of information that might suggest any unresolved disharmony between groups or classes whose fortunes have diverged in American life. In her book-length examination of US history textbooks, FitzGerald noted that the portrayal of minorities as contented citizens untroubled by societal problems carried over even to the illustrations. Invariably depicted smiling, it was as though “all non-white people in the United States took happy pills,” she wrote.

No wonder, then, that discourse among today’s American adults is studded with such ahistorical howlers as the notion, fashionable among certain conservatives, that Martin Luther King typified the ideology of the modern Republican Party—a gambit that can only succeed by pretending away King’s advocacy of labor unionism and “a radical redistribution of economic and political power,” in his words. Or, on the flip side, the urge among certain leftists to interpret King through a prism that minimizes his radical commitment to New Testament theology. And if Americans can manage this much misunderstanding about a man who left behind a documentary record as extensive as King’s, there may be no limit to how badly we can misrepresent a figure like Robert E. Lee, or John Brown, or Sitting Bull.

By Zimmerman’s reckoning, the problem goes beyond assessments of this or that historical figure. America’s textbook bargain serves to short-circuit critical inquiry in broader terms. “Each ‘race’ gets to have its heroes sung,” he writes, “but no group may question the melody of peace, freedom, and economic opportunity that unites them all.”

Which is ultimately no less suspect than massaging the story of the American Revolution to gel with the US Department of War’s public-messaging aims during World War I, or recasting the history of the Confederacy to placate apologists for antebellum and postbellum apartheid regimes. To which Zimmerman adds an additional charge—that the bargain in fact violates the central theme that US history textbooks share: the freedom of the individual.

“Textbooks depict America as a beacon of personal liberty and opportunity, lighting the way for an often tyrannical and barbaric world,” he writes. “Yet by stressing this sunny story and downplaying darker ones—especially poverty, racism, and imperialism—the texts actually inhibit the very individualism that they venerate. If the books took personal freedom seriously, they would encourage students to develop their own perspectives about the nation and about its various races, ethnicities, and religions.”

After all, over the past half-century “historians have engaged in a rich debate about the ‘liberal’ character of American society. Were slavery and nativism simply bumps in the road toward America’s democratic destiny, brief interruptions of the parade of progress? Or did the traditions of liberalism and racism work in tandem, each one defining the content and contours of the other? Is America a ‘uniquely free’ country, as its textbooks proudly proclaim? What does ‘free’ mean, anyway?”

Elementary school children might not be ready for such discussions—nor, perhaps, are sixth-graders like Zimmerman’s former pupils. “But these are all questions that high school students can answer—indeed, that they must answer, if they are to develop the critical capacities that democratic citizenship requires,” he argues. Culture itself is less a monologue than a many-sided debate—especially in a nation as ethnically, religiously, economically, and ideologically diverse as the United States. “So we should teach it as a debate, pressing our students to join America’s arguments rather than pretending that we settled these differences long ago.

“You cannot praise America for cultivating individual freedom of thought, then proceed to tell every individual what to think,” he concludes. “But that is exactly what most of our schoolbooks continue to do.”

There are significant impediments to changing that status quo. It’s hard to generalize about an educational system comprised of 14,000 school districts, several million teachers, and tens of millions of children. “But I think,” Zimmerman says, “that especially in history, social studies, and English, there are serious inhibitors on teaching. A lot of the teaching tends to be rote-driven, textbook-driven, and not discussion-based.”

That has been exacerbated, in his view, by the fact that “in the past 20 years we’ve made schools into standardized-testing machines.” Zimmerman notes that whenever he speaks about his pedagogical ideas with educators, he hears the same lament. “People will say, ‘This is a very nice idea, and I certainly endorse it in principle—but when am I going to have time to have that debate about whether we should have gone to war with Vietnam? I’ve got 15 minutes for the Vietnam War before I have to move on to Watergate. And by the way, there’s going to be a question on the standardized exam and it’s not going to be Write an essay about whether we should have been in Vietnam; it’s going to be Who was Ho Chi Minh?’ So the rise of this standardized testing accountability regime has been a huge inhibitor.”

It doesn’t help that American education schools tend to offer a “hollow and decidedly anti-intellectual brand” of teacher training that’s long on “arcane” jargon and short on “serious intellectual initiation into the subjects in which teachers will have to instruct students,” as Zimmerman has charged in the New York Review of Books. (American universities, he argues in The Amateur Hour, are dogged by the opposite problem: professors have deep knowledge about their subject areas but rarely receive any training in how to effectively teach it.) And current K–12 practices further limit the ability of teachers to learn from one another. “Many other advanced countries have institutionalized critical commentary by peers and also provide intellectual support to improve skills and learning as part of teachers’ professional practice. Japanese teachers even have a separate word for this process, jugyokenkyu, which is built into their weekly routines,” Zimmerman observes. “We don’t even have a word for it.”

But in Whose America, he identified what would seem to be an even larger obstacle to critical education in US public schools: the American public itself. “As one of my students once quipped, ‘You’ll never see a parents’ group called Americans in Favor of Debating the Other Side in Our Schools.’ Citizens enter the arena of curriculum so that a particular view or attitude will find a place within it. The last thing they want, it seems, is a multiplicity of perspectives.”

But two decades later, Zimmerman thinks the moment may finally have come.

“The only way that changes—and this is going to sound tautological—is if we as citizens decide it needs to,” he says. “The polling literature shows that Americans are deeply dissatisfied with their political culture right now. Americans acknowledge how polarized and poisonous it is, and they don’t like it—Democrats and Republicans. And that provides an important wedge and opportunity: because that suggests to me that there are more Americans who want to see schools actually tackle that, and demonstrate something that’s better.”

Doing so, he believes, will require acknowledging and confronting a fear that has grown as public discourse has atrophied.

“In both K–12 and higher-ed, one of the key inhibitors is that people are afraid. They don’t feel they have either the duty or the right to speak their minds.” A 2020 survey by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), encompassing nearly 20,000 students at 55 colleges and universities, found that 60 percent reported having felt unable to express an opinion on campus for fear of social or administrative repercussions.

“And large numbers of faculty, both Republican and Democrat, say the same thing,” Zimmerman contends. “That is an enormous inhibitor. We live in a culture of fear. Political partisans are demonizing one another, and making us fear one another. But at the same time we actually fear speaking, period, because we don’t know what people on the other side—or even people in our own tribe—are going to say. And I don’t believe that in higher education, we’ve really acknowledged that. After the FIRE survey, how many university presidents said, ‘OK, this is bad, we’ve got to change this’? I didn’t really hear it. And as per the cliché about Alcoholics Anonymous, we’re really not going to change that until we acknowledge that we have a problem.”

Education is an inescapably political enterprise, as Aristotle articulated long ago. “And in America, especially at the K–12 level, schools were founded for explicitly civic purposes,” Zimmerman says. What animated the common schools movement of the 19th century was the conviction that they would function, in the words of one advocate, as “pillars of the republic.”

“It wasn’t pillars of higher test scores, or pillars of a better job, or pillars of not losing out to China,” Zimmerman says. “It was pillars of the republic because the idea was that we’re making a nation and what we need is an institution that will bind us to one another, and teach us the habits and skills of democratic life.”

There is no getting around the fact that different people want different things from our schools, from critical inquiry to civic hero worship of widely varying forms.

“The fact that we have such different views of America is an incredible challenge, because people will object when their view is not affirmed,” Zimmerman allows. “But it’s also a gift: because we shouldn’t have to pretend that we all agree about what the nation is when the kids are in the room—we should expose them to that little secret.

“And in some ways it’s easier to do in situations where there’s more pluralism, where there’s more disagreement,” he suggests. “I think we try to pretend that the classroom should somehow be insulated from the rest of society—that somehow it ought to be a plane that floats above it. And I think that’s an enormous mistake. It is hugely challenging to let all that stuff into the classroom door. But I think it’s diverse enough that it gives us as Americans an incredible opportunity to literally and figuratively school people in our differences.”

That is a learned behavior, Zimmerman stresses. “People don’t come out of the womb doing it. And if we believe some psychologists, it may even be unnatural—we’re just programmed to love our tribe and hate on the others. And certainly we’ve done plenty of that. But I think the best outcome would be to use these different stories to actually engage each other about what we think America is.”

In that vein, he sees the New York Times’ 1619 Project—or rather “the debate surrounding” that initiative to examine American history through the lens of slavery’s consequences and the contributions of Black Americans to the nation’s development—as an “incredible opportunity.” But only if it is permitted to function as one analysis, not the analysis. By challenging the “lazy multiculturalism” and thematic sanitization Zimmerman laments in contemporary textbooks, it can help us “to do what we haven’t done, which is really try to use all this diversity to ask ourselves about the larger story.

“Part of the celebration of American freedom, to me,” he emphasizes, “should be teaching people how to arrive at their own conclusion instead of repeating what the textbook says. That’s not an act of freedom; that’s its opposite, an act of indoctrination.”

Which nevertheless always lurks around the next corner.

“One of my concerns is that in some instances the 1619 Project is just becoming a new set of instructions—and that won’t help anybody,” he acknowledges. “The people criticizing it have in some places been unfairly depicted as denialists. Sean Wilentz and Gordon Wood don’t deny the relevance and centrality of slavery and racism,” Zimmerman emphasizes, citing two historians who have raised objections to elements of the Times’ interpretive frame. “Their critique is that they don’t think the project does justice to all the people who have fought against that, creating different ideas and different traditions.”

This happens to be an issue on which Zimmerman has chosen a side.

“I grew up in a vastly more patriotic age. There’s no other way to put it,” he reflects. “One of the things I’ve noticed on this subject—especially with respect to my daughters, who are now 27 and 24—is that we loathe Trump equally, yet I’m offended by him, and they are not. This is an experience I’ve had with my students, too. Because they regard him as an inevitable product of what’s wrong with America. Whereas I see him as this enormous deviation from it. So I’m like, ‘This is horrible because it runs counter to everything that America is and should be.’ And their view is: ‘No! It’s the apotheosis of it! This was a place that was born in racism and oppression, so of course it gave birth to this guy.’ And I’m like, ‘Look, I’m a historian—I’m not going to deny the racism and oppression. But there’s a deep tradition of liberty and freedom that ran counter to that.’”

In other words, he relishes the debate. And the present moment, he believes, clarifies the consequences of an educational regime that shrinks from it.

“I think the biggest poison in our democracy is to assume that somebody who disagrees with you is simply misinformed,” Zimmerman says. “Look, sometimes they are—and that’s important. But there are plenty of people who are equally knowledgeable and equally reasonable and equally educated as I am, and see the world differently. And the biggest poison is this idea that somebody who disagrees with us is either cognitively or morally warped: either they’re just ill-informed and believe things that are false, or they’re just awful people.

“The only way we get away from that is via schools,” he concludes. “I don’t see any other way.”

I think there is value in this philosophical discussion, but I was left wanting more. Where is the practical half? I was reading this, and reading and reading and at the end, I was like dang you just made me read so much about your opinions on these problems and how they are seriously inhibiting intellectual progress and you didn’t even propose some kind of practical solution? (Let’s assume the problem has been, as you say, “acknowledged”) What should classroom educators do? What should superintendents do? What should policy makers do? What should students do? What should parents do? Forgive my frankness, I’m an impatient educator who likes to see progress today, not tomorrow.

Thank you so much for this wonderful profile of Dr. Zimmerman. His comments were fact-based, informative, insightful, nuanced, reasonable, and not tendentious in the least. I wish that more academics, public intellectuals, and political pundits emulated him!