The view from inside Penn’s digital-media-design major: “We are an annoying, fidgety, break-things-and-fix-it cult—who make horrible noises.” Others might say that the program attracts some of Penn’s brightest, most dedicated, and most creative students.

By Samuel Hughes

Sidebar | Chilly Scenes of Ninja

Ben Franklin is dancing up a cyclone. I mean he is kickin’—grinding, bumping, push-pull-pushing, vogueing to some high-octane funk by Basement Jaxx—Let it all out, doin’ my thang/Boom-boom-boom and a-bang-bang-bang—big feet slip-sliding along a multi-colored disco dance floor—He’s a wonderfully grotesque caricature of Penn’s founder, this big-butted, blue-waistcoated 3-D groove-master with the studiously cool expression behind his bifocals. I can’t stop watching him—and it’s not as if I lack for images of Franklin in this part of the world.

Dancing Ben is one of many upstart creations of Penn’s Digital Media Design (DMD) program, an undergraduate major that fuses computer science with fine arts and communication theory. It’s a sort of high-tech, discipline-hopping marriage of science and art, theory and practice, and as I watch Dancing Ben move I half-expect him to start spouting some jive hip-hop version of “all things useful, all things ornamental.”

“Franklin would have loved DMD,” says Amy Calhoun C’82, the program’s high-revving associate director. “It’s everything that I think he was talking about, as far as taking all of this technology and this understanding of cognitive science and perception and how the brain works—and putting it into something tangible that people can use.

“What differentiates DMD students from students who have gone to art school,” she adds, “is that they not only understand how to make an appealing image, but they know how to make the computer do what they need it to do.”

Consider what Dancing Ben’s creator, Salim Zayat EAS’01, had to do to get him up and boogying. First, after poring over countless portraits of Franklin, Zayat created his own “overly rotund” image, using old-fashioned pencil and paper. (“All my character designs have an element of cartoon to them,” he says. “It’s just the way I see the world.”) After scanning the drawings into Adobe Photoshop and saving the images, he made the 3-D models using Alias-Wavefront’s Maya software. For the textures he drew on Photoshop, and to speed up the coloring process he used a Wacom digital-painting tablet.

At that point, he needed a movement model, so he enlisted a DMD student named Matt Leiker EAS’05—despite the fact that Leiker “could not have been more than 120 pounds soaking wet.” But he could flat-out dance, so Zayat brought him into the LiveActor virtual-reality facility in the Moore building (just up the hall from the ENIAC Museum), dressed him in a sensor-studded Lycra spandex suit, and recorded his funky dancing on the motion-capture system. He then mapped the dance-movement data to the Ben Franklin model, using a software program called Filmbox (now Mocap). That turned out to be even harder than it sounds, thanks to Ben’s highly exaggerated proportions.

“Unfortunately, the discrepancies in body type [between Dancing Ben and Dancing Matt] caused a lot of what we call ‘interpenetration,’” recalls Zayat. That, he explains, “is when body parts go through each other.”

Getting all the body parts to behave took many hours of cleanup work at the computer. But the final result is a poetry-slam in motion.

“We’re telling these kids that it’s OK to go to Penn Engineering and be creative,” Dr. Norman Badler is saying. “Because tucked away somewhere in their psyche is an artist. When you read their application letters, it’s a constant theme: ‘I’m really good at math and working with computers, and I’m also really good at art.’ This gives them a chance to get a good grounding in computer science—yet let their inner artist flourish.”

Badler is the mastermind behind the DMD program, which was born in 1998, the same year that The Matrix came out. (All revolutions have their fabled timelines.) He’s a very personable guy—calm, bearded, matter-of-fact, reassuringly competent but with a gentle twinkle that hints at vast virtual worlds filled with strange virtual beings, most still unborn. At Penn, his professional avatars include: professor of computer and information science, director of the Center for Human Modeling and Simulation, associate dean for academic affairs in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and now head of DMD. Because of his founding role, the program is based in SEAS even though its curriculum draws deeply from the School of Design (née Graduate School of Fine Arts) and the Annenberg School for Communication. (It also requires six classes in mathematics; four in physics, biology, chemistry, or psychology; and seven in the social sciences or humanities.) “It’s the nature of the beast that if you come forth with a project, you get to be in charge of it,” Badler says drily.

He is also a certified Big Deal in the world of computer graphics. Some 17 years ago, in the misty dawn of virtual reality, he created Jack, the first virtual human being. Although Jack left the University in 1996 (sold to a start-up company and now distributed by an information-technology-services company named EDS), Badler is still up to his elbows in virtuality. He was one of the founders of SIGGRAPH—Special Interest Group in computer Graphics—whose annual conference is considered the apex of the computer-graphics field. Today, the Virtual Humans Architecture Group lists him as an “expert adviser.”

DMD could not have existed 20 years ago, he acknowledges, or even 10. “There were not sufficient computational resources to allow students to develop projects,” he says. “We’re dependent on the PC revolution. There’s also a significant amount of commercial software that helps people do things that they couldn’t before.” And because of his pioneering background in the field, Badler is often able to get students the latest “proprietary software” from his industry contacts.

“He can call Ed Catmull, who is the head of Pixar,” says Calhoun. “Very few people can get through to Ed Catmull. Pixar gave us 10 licenses to RenderMan [software], which normally sell for around $10,000 apiece.”

But Badler wants his students to be able to do a lot more than just use these sophisticated tools.

“Our challenge as educators is to make sure that our students understand what’s inside,” he says. “In fine-arts courses, the encouragement will be on creativity, usually with existing tools. In engineering, we’re more concerned with what’s going on inside these tools, inside the software, and how to make it work to your advantage if it doesn’t do what it already comes with. To prepare students for a future career in DMD, it’s very important to give them the foundation to go outside—literally—that software box.”

“DMD is unique in that the industry is organically developing connections between art, technology, and communication,” says Dr. Joshua Mosley, assistant professor of animation in the School of Design. “And in the same way as that’s happening, we’re finding our way and discovering what those connections are. The program is flexible and rigorous enough that it’sadapting as the industry is adapting.”

Mosley and Badler co-teach a course titled Virtual World Design, in which students must create a 3-D, interactive virtual world. According to Amy Calhoun, the contrasting lecture styles have often been “most entertaining” to watch.

“Dr. Badler would start off by saying, ‘All right, here are the rules: You’re going to create a 3-D interactive world. I want three characters, three interactions—which can be a sound, them running into each other, some kind of interaction between the characters. And it has to exist in space.’ And then Joshua would say, ‘But I also want you to think about the fact that a virtual world could be a world of love or a world of pain.’”

One student (Alex Chen EE’04 W’04), she recalls, created a program that he described as an “exercise in pain endurance.”

“It was a virtual world, where wherever you walked in it, it would flip over, so it would make you motion-sick,” she says. “It made horrible noises, like fingernails on the blackboard, like screaming and howling and screeching. He said, ‘It’s an experiment in endurance of unpleasant things.’ Dr. Badler and I were like, ‘Yup; that’s annoying.’ And Joshua crouched down on the floor and proceeded to watch it for eight minutes, and when the project was over, he said, ‘That is so disgusting—it’s fabulous!’ And I thought, ‘And this is why you need them together—because the professor completely got what this kid spent all this time on.’

“They both were absolutely speaking the language of their discipline,” she adds. “And that’s why so much of this program is translation. Because it was only the DMD kids that could follow these instructions.”

“We’re still experimenting with the format that’s best,” says Badler. “But each year I’m just blown away by the capabilities of the students taking the course.”

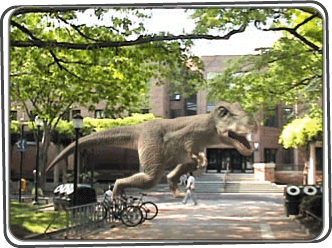

There’s a Tyrannosaurus Rex on the loose.

It’s stomping up Locust Walk, turning its great razor-toothed head from side to side as it goes, the scarred skin on its massive body glistening in the morning sun. It hesitates in front of Steinberg Hall-Dietrich Hall and finally turns toward me and lunges forward with a great soundless roar.

T-Rex on Locust Walk is the creation of Ray Forziati EAS’04, who hatched his terrible lizard in 2001, after an eight-year gestation that began when his father took him to see Jurassic Park for the first time.

“They just looked so real,” he says of the dinosaurs. “The movie’s characters claimed they were a miracle of genetic engineering, but even at 11 years old, I knew that couldn’t be. How’d the filmmakers get those dinosaurs in the movie? Robots? Puppets? Then I finally found out. They did it with computers. The dinos were digital. And a DMD student was born.”

Fast forward half a dozen years. Forziati, now in high school, was sorting through a pile of discarded college brochures when a list of Penn’s majors caught his eye. “I saw Digital Media Design listed, and my mouth dropped,” he says. “I had been tirelessly looking for a program even named that.”

His research into other schools clinched it. “DMD was the only undergraduate program that offered such a good balance between art and computer science,” he says. “Other schools were either very technical schools with pure computer-science majors or art schools that gave out art degrees. DMD offered both.”

By the summer of 2001, Forziati had finished his freshman year, and was ready to create his own T-Rex and set it loose on Locust Walk. He watched specific scenes in the Jurassic Park movies “over and over and over until the tape got a bit ruined,” he says. “I had to find out where the joints were, where the weight was, what skin jiggled, how it walked. Industrial Light & Magic, which did the visual effects for the movies, had done the research. I was just trying to recreate that effect.”

By then—having devoured TV specials, books of dinosaur artwork, and special-effects magazines; downloaded software; chatted with experts online; and begged big animation companies to show him around—he was ready to take his research to another level.

“I walked around my room pretending to be a dinosaur,” he says. “Yes, this scared my family a lot. Having your 19-year-old son stomp around the house like a six-ton reptile is just plain weird.”

After modeling his T-Rex by hand—“virtually sculpting it in 3-D”—he animated it by setting key-frames at various poses. “The textures were painted on the dinosaur model by hand in 3-D,” he explains. “I actually made ‘cuts’ and scars in the T-Rex’s skin.”

The hardest part was incorporating the dinosaur into his live-action background footage of Locust Walk, which “bounced around” a lot.

“Once I had the footage in my computer, I had to track the real camera movements to match up the virtual camera with it,” he explains. “Otherwise, the dinosaur would ‘float’ around the footage when I composited it in. After tracking the camera in the footage, I applied its movements to the virtual camera, and lo and behold, the T-Rex looks like he’s standing on the ground.” A ’saur is born.

“I have no doubt that Ray Forziati will be one of the great animators of his generation,” says Dr. Paul Messaris ASC’72 Gr’75, the Lev Kuleshov Professor of Communication and the Annenberg School’s DMD representative. “But some of the most talented DMD majors have worked in other areas as well.”

To get a sense of DMD’s possibilities, consider the following projects by its students and alumni:

- Heroes of AIDS in Africa, a documentary by Neil Halloran EAS’01 that chronicles the life and work of five individuals in southern Africa dedicated to “bringing health to their people in the midst of the African AIDS epidemic.” His Web site (www.aidsinafrica.net/) provides interactive epidemic maps that display a grim range of statistics of HIV levels now and in the future among the various African nations.

- An interactive chat room, in which participants created their own characters and could see the “people” they were talking to. It was the senior project of Kevin J. Martin EAS’01, now co-chief executive officer of 4e Consulting, a business-technology consulting firm.

- Crime Stoppers!, a highly entertaining animated crime-show spoof by Salim Zayat (www.salimzayat.com).

- Wired Awake, a poetically surreal digital film by Neil Chatterjee EAS’01 about a crashing insomniac who allows himself to be connected to a machine that takes his consciousness to an even more hallucinatory dreamscape. Chatterjee and Omer Baristiran EAS’02 CGS’04, incidentally, are co-creative directors of AlternativeNRG Media, which Chatterjee describes as a “mom-and-pop industrial video house” doing high-end animation, sound, and production, as well as writing, editing, and distribution (www.alternativenrg.com).

- The Heart Sense Game, which targets heart-attack patients and teaches them how to deal with their condition. Though conceived by Engineering Professor Barry Silverman, DMD’s Kevin Chan EAS’02 helped develop a dynamic animation system for the game’s characters, so that their movements could be “easily programmed on the fly by a more user-friendly editing application.”

- Hellbound, a computer game that one of its creators, Paul Kanyuk EAS’05, de-scribes as an “irreverent adaptation of turn-based military strategy gaming to biblical melodrama.” Kanyuk’s description of the problems involved in creating and animating devils, angels, imps, cherubs, and the like is hilarious—and somewhat mind-boggling in its detail. (“After about 20 hours or so of work,” he notes, “I could get devils to poke their pitchforks on command in a manner independent of their body movement.”)

- A Web-based mapping program by Craig Modzelesky EAS’05 that mines thousands of different news sources for references to locations and, based on the frequency of citations, represents the data visually, in the form of a map. “Locations that appear in the news (with respect to their frequency in aggregate—over those thousands of sources) pop up in appropriate positions on the map,” says Modzelesky. “Clicking on those event markers brings up a list of corresponding articles. It’s a reversal of the norm. You see an unfiltered view of global events and then choose to read about what’s important to you.” (He hopes to have it up and running on his Web site by the end of August: (www.craigmod.com).

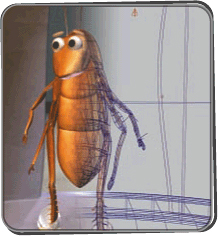

- Dink!, an animated 3-D video about a group of suspiciously Penn-like student — cockroaches arriving in their tin-can “dorm” for the first time (www.seas.upenn.edu/~omerb/video/dink.mov/). The creation of a DMD-dominated group of students at the University Television Station (UTV-13) led by Omer Baristiran (who hopes to become “the Steven Spielberg of Turkey” some day) and Ray Forziati, it won an award from the Association of Higher Education Cable Television Administrators, and was chosen to be displayed at this summer’s annual SIGGRAPH convention in San Diego. (That convention, incidentally, is an annual destination for Penn’s DMD students, who make contacts, check out the latest high-tech toys and tools, schmooze, bond, and generally have a ball.)

Julie Saecker Schneider, director of the fine-arts undergraduate program and the School of Design’s DMD representative, notes that DMD students “will so easily move from drawing or painting to video or animation.” She thinks for a moment, then adds: “It’s as if they’re no longer bound by traditional media. It’s all open to them, because they have established a comfort zone with this piece of plastic on the desk.”

“I had a psychology professor call me one day and ask me if we were a cult,” says Calhoun. “He said, ‘I have a bunch of your students, and they all sit together, and when I ask a question, they all raise their hands together, and it’s really freaky.’”

She laughs delightedly. “And I said, ‘It is a little creepy, you’re right. But for many of them, it’s the first time that they’ve ever met other people who could care about the stuff they care about.’”

Neil Chatterjee says that as soon as he decided to transfer into the program, he started running into people who felt the same way he did about offbeat aesthetic and technical matters: “How much they hated Arial [the font], that kind of thing. Really dorky discussions. It takes a sort of extreme nerd to test such thoughts.”

“DMD students are always a little bit weird,” says Nathan Schreiber EAS’02 C’02, who also majored in economics and whose sometimes-hilarious Terrell Quimby comic strip won the College Media Advisor’s award for best comic of the year. “It’s a pretty tight community. The curriculum is a little bit overwhelming. You’re just all over the place. But you can usually look around and see someone with a crazy haircut, and you know they’re in DMD.”

No more than 20 new students are admitted each year; this past year there were just 73 in the whole program. Competition is extreme, and Calhoun is adamant about not taking students who won’t be able to handle failure—because in DMD, some failure is almost inevitable.

“I call it the Fragile Ego Major,” says Calhoun. “Because no matter how good you are at one of these, you’re going to be really bad at one aspect of it. Most people are not equally left-brain and right-brain. And you have to confront that.

“One of the challenges with DMD over the past five years is finding the right students,” she adds. “There probably won’t be, at any given time, more than 300 kids in the country who want to do this. And there probably won’t be more than 50 or 60 who are capable. It’s asking for very strange skills that most people don’t have.”

“We make sure our students are well-grounded in computer science,” says Badler. “If anything, that’s the part students have done the most grousing about. I firmly believe that’s the ‘It’s good for you’ stuff.

“Most of our students are very talented artistically,” he adds. “That comes naturally to them. Math comes harder—and working harder on that is healthy. But I think we have a good mix of courses.” Badler also believes in pairing his undergraduate DMD students with Ph.D. students. “There are mutual benefits,” he explains. “The Ph.D. student gets an effective pair of hands to work with, and the undergraduate gets a research project where the problems are not known. Selfishly, it helps our research enterprise; less selfishly, it gives undergraduate students a sense of what it’s like to be an engineer.”

Some of the more engineering-oriented students struggle far more with fine-arts courses than with computer science. “Art classes really kicked my butt,” says Kevin Martin. “But in the same breath, they were the most interesting and fulfilling.”

Julie Schneider notes that she gets “two distinctive kinds of students” in her fine-arts courses. “One is code-writers, computer geeks. Then we get artists, who are right-brained, who love anything that involves creating on a computer. They do code-writing because they have to, but their first passion is how it looks.” She admits that she is “still waiting for a good story-writer to come along.”

Calhoun agrees—up to a point. “The one thing we’re not focusing on right now in our curriculum is, ‘Is the story any good?’” And yet, she adds: “Most of the kids who have been in the program have always had this internal audience in their brain, and everything they do, they’re playing to that internal audience. It’s probably a sign of psychosis! They’re constantly analyzing for content and how people will react to something. So when they first get in communication classes, it seems so self-evident to them—they just can’t believe that anybody is sitting down and discussing why some people cry and some people laugh at Titanic.”

The communications component of DMD is “devoted to answering the question: How do people react to media—and why?” explains Paul Messaris. Under-standing those reactions, he says, “makes our students better creators of media.”

“We’re not fine-arts students, communication students, or computer-science students,” says Forziati. “We’re a little bit of all three, and that separates us into our own group. Because of that, you start to see us ‘evolve’ some similar characteristics that one needs in order to survive the complex world of DMD.”

Among those characteristics is a willingness to dive in and fix problems—and take risks.

“They don’t follow rules well,” says Calhoun. “And that’s exactly what makes them good DMD students. And it’s probably what makes them a pain in the neck to everybody else. We are an annoying, fidgety, break-things-and-fix-it cult—who make horrible noises.”

Her use of the first-person plural there is telling. Many of the DMD students and alumni interviewed for this article went out of their way to toss Calhoun bouquets, in terms ranging from “den mother” to “counselor of the year,” while Badler called her the program’s “secret weapon.”

“Enough cannot be said about Amy,” says Salim Zayat. “She is everything to this program. She toils endlessly to improve it, constantly getting student feedback about everything, always fighting tooth-and-nail for them. She makes the program succeed because she gets us to believe in it.”

“DMD feels more like a close-knit family or club than an academic program,” says Forziati. “When you sit back and look at the work done by DMD students, you get chills. Just being able to struggle for so long to work on something and make it good and then to have people like it and critique it—that’s a great feeling. It makes you proud to see what DMDers are capable of. And DMDers are proud to be DMDers!”

In Calhoun’s view, the hard part about DMD is that “suddenly they’re surrounded by other people who might be as good or better than they are.” The flip side of that competition, though, is that “there’s also somebody to talk to—and what they learn from each other is far more valuable than what we teach them in the classroom.”

“Everyone has their own niche in DMD,” says Forziati, “so if you don’t know something, there’s bound to be someone who does. Want to know the best software to use for that animation? Which colors to use on a Web site? What shutter speed will work best in that light? Ask around. Someone will have your answer!”

Often as not, those answers will be discovered in the small hours of the night. DMD students appear to be pathologically addicted to wildly ambitious group projects.

“Many, many, many all-nighters are part of a DMD student’s life,” says Kevin Chan. While he admits that some were the result of “poor time-management” (a recurring theme in DMD conversations), “many others were the result of pure interest and zeal for a particular project.”

“With three major components of study in the program, it’s extremely challenging trying to find a way to juggle the very different classes,” explains Forziati. “Computer science alone is hard enough! Constantly switching your brain back and forth between such opposite things as algorithms and color is not easy. Which do you spend more time on? Will you be all night in the computer lab or the fine-arts building?”

The fact that DMD is so dependent on practical experience and extracurricular projects “just adds another 10 pieces to the impossible time-management puzzle,” he notes. “Come to think of it, the hardest part about DMD might, in fact, be accepting that you will never be able to do everything you want!”

Given the highly demanding nature of the DMD course-load, says Omer Baristiran, “your ego would break if you were alone. But you’re not alone. Without that factor, you would really go crazy.”

Not long ago, Amy Calhoun recalls, the head of a small animation company had a decision to face. He wanted to option the rights to a story that featured animated monkeys. His fallback story involved animated pigeons.

“One of his animators said to him, ‘Monkeys are really hard, because hair is hard,’” says Calhoun. “And he said, ‘How about birds?’ They said, ‘Feathers are hard, but they’re not as hard as hair —go with the pigeons.’ So literally, the drawing that it would take to produce the film dictated which story he got to make a film.”

Keeping up with the hyper-evolving technology behind the computer-graphics industry is a staggering challenge, albeit one with big-time payoffs. That animation-company president concluded that DMD provided the “perfect education for somebody who was going to go into producing, directing, or running film companies, because you understand all the aspects of the technology,” says Calhoun. “And you won’t buy into things that are impossible to do.”

In places like Industrial Light & Magic or Pixar, “you have two teams of people: the artists and the computer scientists,” she points out. “But you have nobody who’s equally educated in both, who can bridge that gap. And those two groups cannot speak to each other, because they don’t share any common vocabulary. That’s what our students do—they translate.”

Exactly what students will be doing with DMD degrees a decade from now is probably an unanswerable question. Asked where he sees the program in 10 years, Badler responds: “On a technological line, the future will get both better and worse. It will get better because increasingly powerful software systems will be available to students. The bad side is, increasingly powerful software systems will be available to students—and they will perceive less of a need to learn the programming side of digital media.”

DMD alumni, of course, have a slightly different view of the program’s future. Kevin Martin thinks the future will be “wherever the students take it”—and that the only limit will be their imaginations.

“Going through the process of developing an idea from concept to creation teaches one thing: how to adapt and therefore teach yourself,” he says. “The DMD program is based on this thought-process. You may be trying to do something that no one has ever done—at least no one at Penn, faculty included. But that doesn’t meanDon’t do it. It means Figure it out.”

“With DMD, it’s a frontier, and it’s an exciting frontier, but at the same time, you’re out on your own a lot of times,” says Nathan Schreiber. “It’s a dynamic field, one that’s constantly changing. That’s one of the things that makes it slippery as hell.”

SIDEBAR

The Chilly Scenes of Ninja

A group of DMD filmmakers goes for the gold in a West Philadelphia graveyard.

Neil Chatterjee EAS’01 was getting worried. It was a bitterly cold day in February, and he and Sophomore Josh Gorin and a pack of other DMD students were prowling about Woodlands Cemetery, stalking each other with guns and Samurai swords. West Philadelphians aren’t the most skittish folks in the world, but still—the sight of black-clad 20-year-olds digging up graves, pointing semi-automatic weapons, sword-fighting, and hurling sharp metal Ninja stars at each other tends to attract the wrong kind of attention. Even with two young boys dressed in Penn sweatshirts hanging around the “set.”

So for most of the shooting, whenever Chatterjee and the rest of the crew saw anyone not related to the Ninja movie approaching, they’d yell out “Red Light!” Whereupon everyone would drop their weapons and pretend to be doing something innocent, like trying to rub sensation into their frozen feet or taking the flat-lining digital camera into the running car to warm it back to life.

But as crunch-time set in, and they had to wrap up the shooting or blow the deadline, they abandoned all caution and just kept shooting their film about a gang of grave-robbers set upon by an avenging Ninja. And somehow, in a period of 15 days, they managed to conceive, plot, script-write, shoot, edit, overdub, digitally alter, and finally submit their film to Activision, a video-game publisher that was offering a $15,000 grand prize to the makers of the best Ninja-themed film.

“We got this come-on from Activision 15 days before the deadline,” says Chatterjee. “We said, ‘What the heck, we can do it.’

I didn’t sleep a lot during that time.”

Once Chatterjee came up with the film’s plot, they wrote the script in 24 hours. Before they rented the black Ninja costumes, recalls Amy Calhoun, “Neil said, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if we put them in white costumes and it snowed? But there’s no way I can possibly count on it snowing.’ So they rented black costumes and black weapons.”

And, of course, it snowed—a lot. “So they’re now the dumbest Ninjas in the world, because they’re standing in black costumes in the snow!” laughs Calhoun. “You can spot them a mile away! But you know, for the $400 or whatever they had to buy costumes—it worked.”

Gorin and Chatterjee, the mainstays of the film, ran into problems they could never have foreseen. “Basically, I learned that you can’t be too prepared,” says Chatterjee. “If you think you’ll start shooting in a month, you’ll start shooting in six months.”

Without divulging crucial details of plot, they also needed two young boys, which is where Harry and Blair Bodek, the sons of Hanley Bodek C’77 and grandsons of Gordon Bodek C’42, came in.

“Neil and Josh called me one day and said, ‘We need little kids, preferably, like, 8 and 11,’” recalls Calhoun. “I said, ‘I don’t purvey children—no, I don’t know any little kids.’ So I called a friend who used to work in the College and now is in SAS development, and she said, ‘I know little kids.’” Chatterjee says the young Bodeks were “great sports,” and notes that beyond just acting in the movie, they rewrote their dialogue, since they thought that the lines they were supposed to speak “didn’t sound realistic.”

The DMD crew finished the movie—without getting arrested—at a cost of $700. Every piece of sound, except for the dialogue at the end, was recorded in Chatterjee’s bedroom. At one point, he was having trouble getting the right sound-effect for a Ninja head-butting a grave-robber, so he finally he took a melon and smashed it against his chest. “It created the right noise,” he says, “but it knocked the wind out of me.”

Myriad visual details—such as recreating Japanese characters spelling out Ninja on a tombstone—had to be digitally overlaid onto the footage. “The kids who worked on it are all super-perfectionist—they didn’t want to turn it in,” says Calhoun. “They’re like, ‘No, there are still things we need to fix.’ But there was no time. By sending that in by the deadline, it taught them that in film and video and art, you can always tinker and make it better. But at a certain point you’ve just got to pull the plug.”

Two months later, they got a letter notifying them that they had won the $15,000 grand prize.

“It was a hoot,” says Chatterjee. The whole project was “just pure silliness,” he adds. “We’re not even Ninja fans.”

Those interested in seeing the Ninja Movie can do so at: (http://www.tenchuwrathofheaven.com/).