Animal behaviorist David White is teasing out the mysteries of cowbirds at the junction of Heredity and Environment.

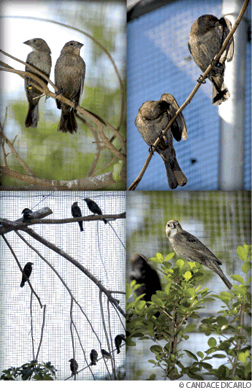

By Samuel Hughes |Illustration by Gina Triplett & Matt Curtius | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Mr. Lonelyhearts looks a little piqued. He’s been letting himself go—lost some fights and some feathers from his breast, and is now wandering around the Bloomfield Farm aviary like a lost soul. His female consort died at the beginning of the breeding season, and as of this warm June morning he has yet to bounce back—even though the season is still in full sway, bursting with courtship and song, competition and copulation. Given that brown-headed cowbirds are your basic relentless reproductive juggernaut, his behavior is a little puzzling.

“I don’t know what to make of this widowed-male phenomenon,” Dr. David White is saying cheerfully. “If a male’s female dies, it’s just hell for him. He just shuts down for the year. If he’s a top male, he comes right down to the bottom.”

White is an assistant professor of psychology, animal-behaviorist division, and my guess is that if he could put Mr. Lonelyhearts on the couch, his advice would be: Quit moping and move on. Since male reproductive success (to use the language of evolution) is limited only by the number of copulations he gets, “the male should not be making this kind of investment in a female.”

You could understand it, White adds, if a female stopped playing the mating game for the season when her male died. She’s the one who has to take the trouble to find a high-quality male. Yet female cowbirds are “ready to go the next day” with another male. Birds have their own agendas.

This is the kind of conundrum that White has been studying in his large, netted aviary, just north of the Morris Arboretum. There’s another aviary nearby, and he’s building a third, but the main action is inside this 60 x 20 x 12 foot cage. Strewn throughout it, like something out of a B-movie set, are dead trees and branches for the birds to flit about. At one end is a small wooden coop, ripe with rotting seed and droppings; in the middle are a couple of lawn chairs, where White and I sit and watch the 12 juvenile males and 11 females go through their complicated fandangos. (He identifies them by the colors of the bands he’s put around their legs.) They pretty much ignore our presence, which is one reason it’s such an oddly entertaining scene: equal parts high-school dance, co-ed summer camp, and seedy singles pickup bar.

Cowbirds aren’t the only feathered critters here. There are also a few juncos, courtesy of Dr. Deborah Duffy, his post-doctoral fellow. Though White dismisses them as “the little flittery ones with no character whatsoever,” the juncos could play an important part in his studies. If they build their nests and lay eggs in them, then cowbirds will lay their eggs there, too.

Getting the juncos to raise the baby cowbirds wouldn’t just mean less work for White, who during Prime Time (the breeding season) gets up at brutal hours of the morning to hand-feed the little beggars. It would also be replicating nature. Cowbirds bring the whole “It takes a village” thing to a new level, laying their eggs in Other Birds’ Nests (OBNs) and then flying off without a thought to child support. This may not be good for the songbirds that end up raising baby cowbirds. (Only a small number of the roughly 220 species that find cowbird eggs in their nests will recognize the scam and pitch the squatter eggs out.) But it does give the older cowbirds a lot more latitude to explore their options.

“Cowbirds are removed from all the parental-care duties,” says White. “And that, trust me, is a huge constraint on behavior.”

White uses the phrase “developmental ecology” to describe the complex interplay of the birds’ early surroundings and their DNA. It turns out that Cowbird Territory is right at the crossroads of Nature and Nurture—making it a very rich and fertile field of study.

“Really, it’s a species with no hard and fast rules,” he says. “Through different developmental trajectories I’ve produced birds that can be promiscuous, monogamous, polygamous—all of those things usually you talk about as the characteristic of the species, but it turns out that whichever one they end up with depended on its experiences during development. A characteristic of juvenile cowbirds is that you put them in a group and they can change their behavior dramatically within a couple of days, just based on the social milieu of the group.”

There’s some irony there, given that cowbirds were once considered a model of genetic pre-programming. After all, males can sing—and females can recognize—a first-rate cowbird song even if they never heard one before. (And the young ones often haven’t, since they’re raised by other species.) But put them in an environment where they have social options and different experiences, and suddenly their slate is wiped almost clean. Traits the birds display during the breeding season—the way a male counter-sings or approaches a female—are shaped by their surroundings. And some of those traits will determine how reproductively successful the birds will be.

White’s work is “very important—as well as interesting—because it can hone hypotheses that can explain social behavior across a variety of species, including humans,” notes Dr. Robert DeRubeis, professor of psychology and former chairman of the department. “His work is also important from an evolutionary perspective because it provides a window into the social competencies that may account for the fitness of these birds.”

“I think that David is really on to something very exciting,” adds Dr. Marc Schmidt, assistant professor of biology, whose own field of study is the neural basis of vocal production and perception in songbirds. “Some of his most recent work even suggests that social upbringing can have a profound effect on embryonic development.”

In The Beak of the Finch: A Story of Evolution in Our Time, author Jonathan Weiner notes: “Today more and more evolutionists are doing what Darwin thought impossible. They are studying the evolutionary process not through fossils but directly, in real time, in the wild: evolution in the flesh.”

White’s aviaries are not exactly in the wild (though they’re a lot closer than the average laboratory setting) and some of his studies will require generations of cowbirds to yield results. But still, as Weiner writes: “The Darwinian view of evolution shows that the unrolling script is always being written, inscribed as it unrolls. The letters are composed by the hand of the moment, by the circumstances of the day itself.”

“We need a currency of evolution,” says White. “And that’s the gene. It’s a very nice currency because it can be immortal; it can be passed on from generation to generation. But nevertheless, which genes get passed on are definitely influenced by experiences. So to really understand, you have to deal with this interaction between genes and the environment in a better way than we have so far. And hopefully, there’s where I end up.”

“It’s really relaxing out here,” White is saying as we watch a couple of young males try to chat up a couple of bored-looking females. “I never appreciated it as a post-doc. The professor I worked with [at Indiana University] always said it was almost a Zen experience to come out and take data. There’s no email, no phones—the birds don’t care if you got tenure or a grant or are writing a paper or they’re ruining your data. They just go on about their business.”

He does seem awfully relaxed—and alert—for a guy who’s been up since 5 a.m. feeding birds, running multiple experiments, analyzing data, and, in his spare time, building a new aviary. But then, animal behaviorists are a pretty down-to-earth bunch.

“It’s because we all have had these task masters, and we’ve had to adjust our lives to these simple little organisms that are running around,” says White, whose tanned features would look at home on the cover of Outdoor Life. “Anybody who’s had to deal with poop in a professional manner …”

White’s original nesting ground was Ontario, an environmental influence that shows up in certain notes of his song pattern (aboatinstead of about, for example). He wasn’t particularly interested in birds as a kid, but when he was earning his Ph.D. at McMaster University in the late 1990s, he soon concluded that they offered more possibilities than his original choice, rats.

With birds, “you can look at two species that may differ only in one aspect of their ecology or their social ecology and compare them very nicely,” he explains. “Mammals do almost all of their communication with scent. With birds it’s all very visual, very bright colors, and much easier to study and observe.” There is even a visual component to their aural communication—at least for human observers—“because you can record their songs and print them out, and that works out to be visual.”

When he migrated to Indiana in 1999 for his post-doctoral work, he started out with quail. Along with psychology professor Meredith West and senior scientist Andrew King, White discovered that when a female quail sees a male having sex with another female, she becomes more interested in the male, whereas a male will be turned off by the sight of a female copulating with another male. But quail—which he describes as “so dumb they don’t know to get out of the way of a lawnmower”—turned out to be of limited interest for White.

And so to cowbirds, which he studied extensively with West and King, churning out papers with titles like “Plasticity in Adult Development: Experiences with Young Males Enhances Mating Competence in Adult Male Cowbirds.” West remembers him fondly as full of energy (“I wish I could bottle it”), devoted to his birds, and generally “fantastic to work with.”

“He’s going to go on to do lots of really interesting things,” she adds. “He’s a great experimentalist, and he’s very good at experimental design.” She points out that White was the one who figured out how to take data by speaking into a wireless microphone connected to a voice-recognition software program, instead of writing down every observation in a notebook.

“The computer can do some great things you can never do on your own, like time-stamp every behavioral interaction,” says White. “Every time I say something, it puts a time on it automatically. And that led to the realization that counter-singing was this important variable that you could program the computer to look for.” Counter-singing occurs when a male sings back to another male within 15 seconds, he explains, and turns out to be “the main predictor of how many eggs a female’s laying” that season.

“Dave was really the sparkplug behind all that work,” says West. “We had been interested in the idea before, but had never had a chance to try it out. Dave put together all the pieces, with my husband [King] helping a lot.”

“Pretty much all I did was buy the software and put it into the computer,” says White. But the system has been indispensable for conducting the kind of experiments he has designed. “I think we’re up to 750,000 data points using this technique, maybe more,” he says. “It would take 20 years to collect that by hand.” He pulls out a sheet of song data for the breeding season. “We’ve taken 17,526 songs and 5,116 near-neighbor points, which is when two birds are beside each other,” he explains. “So we have, for example: OPL sings to MMD, and MMD leaves in response. YLO whistles and DDY just sings an undirected song to nobody. And it just goes on and on and on.”

The spreadsheet shows that an early-hatched male known as W24, for example, has sung one song each to two different females, four to another, seven to another—and 498 to NGW. “It’s pretty clear how monogamous this bird really is,” says White. “This is the kind of thing I do—just go through all these patterns and patterns and patterns and data.”

He came to Penn two years ago, lured by the promise of enough land to build his aviaries—and by the quality of the psychology department.

“The people in the Department of Psychology are just fantastic,” he says. “I gave a lot of job talks in my time on the job market, and giving my job talk here was a singular experience. None of them, except for two, do anything with animal behavior, but every one of them got the ideas, got the important aspects of my work, and were able to ask questions taking it to the next level. It was an intoxicating experience to have this kind of feedback.”

His research also has implications that go beyond the department.

“His work is at the forefront of studying how social interactions and general social makeup within a colony affect social development, including vocal learning,” says Marc Schmidt, the biologist. “I saw his coming here as a great opportunity for us to learn from each other and try and collaborate to study brain function within behaviorally relevant social conditions.”

The high quality of the undergraduates he has supervised has been a pleasant revelation for White, and the benefits have been mutual. “White’s research provides an extremely attractive setting in which undergraduates can gain valuable research experience in both field and laboratory settings,” says Dr. Robert Rescorla, professor and director of undergraduate studies in psychology and a former dean of the College. “This importantly supports Penn’s dual mission of excellence in research and education.”

But always, it comes back to the cowbirds. One doesn’t have to spend much time with White to figure out that he genuinely loves his subject matter.

“They’re a wonderful natural experiment going on out in the wild,” says White. “I shouldn’t say wonderful, because they’re a terrible pest species and they’re crushing all the other songbirds. But they’ve radiated across all of North America, and you can find them in just about any kind of social makeup, any kind of habitat. You have a whole lot of variation out there that you can bring into the lab and manipulate experimentally.”

There are times when the sky goes dark with cowbirds, flying into new territory like a tiny version of the winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz. The females swoop in at dawn and lay their eggs in OBNs, then move on. (If you want to take over the world, it seems, don’t get attached to it. Any of it.)

A female cowbird has to be able to detect the characteristics of a good host nest—one where the diet includes insects, for example—then lay her egg there at exactly the right time. “If they lay their egg even a day later than when the host starts incubating it, their young’s going to be hatched a day after everybody else, and they’re going to be at a complete competitive disadvantage,” notes White, who has slipped a Cadbury candy into a nest as a decoy. “Because the mothers typically don’t feed the ones that need the food; they feed the ones that beg the most.” Cowbirds “seem to grow faster, beg more, and actually hatch a few hours earlier than typically your host species does,” he adds. “And that’s why they get all the food.”

That, in turn, appears to affect the birds’ development. “There were more survivors from the early-hatch than the late-hatch batch,” White notes. “They gained weight faster. There are a whole bunch of early markers that suggested the early guys were healthier than the late guys. They eventually all caught up in weight, but their behaviors are somewhat different, so I don’t know what to make of it yet. After I analyze the data, maybe I will.”

So far, he hasn’t seen much difference between, say, cowbirds raised by red-winged blackbirds and those raised by juncos. But he hasn’t yet attempted a study of the subject. “Cowbirds parasitize over 200 different species, and we’ve never seen any other systematic differences from babies,” he says. “In some parasite species there is a big influence on the young, but I don’t think there is much of that with cowbirds. There’s not much for them to learn early on and they just don’t learn anything.

“I think what happens to a cowbird around Day 30 is that they get hungry, and just about every single cowbird from any kind of nest gets hungry and goes and finds food, and they end up getting together with a bunch of other cowbirds who are also hungry and looking for food. And I think that’s where a lot of the learning begins for them—social learning about how to be a cowbird.”

Three young males—call them Manny, Moe, and Jack—are sitting on a branch, talking trash and getting nowhere. Every now and then they face off with each other; give a big song and a big display—fanning out their wings, then bowing, like sumo wrestlers, and wiping their beaks. Eventually they go off and sing to their females—so far, with little success.

“They’re all kind of doofuses when it comes to courting females,” says White. “It’s getting late in the breeding season and they’ve learned a bit, but—”

Just then, Manny flies over and sings to a female. She sidles away a little, but doesn’t take off. White looks pleased. “That’s a pretty good response for a female,” he says. “So he should take that positively and sing another song to her.” Manny obliges: Glup, glup whistle. “Now another male’s coming in—that’s just gonna mess up his whole technique.”

Contrary to my expectations, the feathers don’t fly. What goes down is more like a very mild, PG-rated version of street rappers battling.

“The facing off between males is usually with song,” says White. “I’ve seen maybe 10 fights in the entire breeding season, so they’re not frequent—but they can be significant to the male. One fight can really change a male’s status if he gets his eye pecked or something like that.” But the juveniles, he adds, “never really get in any kind of serious fights.”

The cowbird’s song provides a tangible way to measure behavior, “because you can print out sound spectographs of songs and compare them directly,” says White. “You can really characterize these songs, quantify them, and it becomes a printout of behavior, if you will.

“What a male is doing at any particular moment in time really is an image of what he’s learned and what social experiences he’s had,” he adds. “If he has a super-fantastic song, it’s probably because he had a social environment where he wasn’t tested, or he’s copied somebody, or he’s been in a good relationship with a female and has been able to hone his song into something good. You can say the same thing for his whole behavior pattern.”

When a male cowbird sings, he takes a big breath, puffs up his chest like Pavarotti, and emits a variation on the theme of Glup glup, whistle. The glup part has an alluring, liquid quality to it, and sounds like a noise your computer might make to indicate an incoming email. The song starts off low—very low, with notes in the barely audible 100-hertz range—but can soar up to a piercing 12 kilohertz when they give their whistle. (Female cowbirds do not sing, though they occasionally give a chirping “rattle” that drives the males wild.)

To get the right sound, male cowbirds switch back and forth between two airways in their throats. This doesn’t happen overnight, White points out. “They spend their whole first year just singing a pile of garbage until that sort of comes in.” Their repertoire is limited to about six variations on a theme—unlike, say starlings, which will incorporate everything from a car alarm to a dog’s barking into their song.

A few seconds after Moe sings, Jack counter-sings: Glup glup glup, whistle. Though White has found counter-singing to be a key predictor of reproductive success, the exact evolutionary motivation for doing it is still open to debate.

The standard view is that it’s “all about male-male competition,” says White. “Males compete for females, so if you can establish yourself that high in the social order, you’ll have priority access to females, and you won’t be disrupted when you’re courting a female. But the more I watch these guys, the less I believe it. In fact, the more I’m starting to see male-male singing as performance for the female. I think it provides the females with more information.”

After all, a female can’t really judge a male’s genetic quality by his song, since he might just be copying another male’s song. In fact, a male with a great song will sometimes be attacked by other males until he learns to tone it down. But if a male sings to another male and can defend himself while doing so—that’s information a girl can use. Females, says White, “are really, really sensitive to that kind of thing.”

On the whole, “we’ve overemphasized male-male competition and underestimated female-female competition,” he adds. “The females are much more subtle and very polite, not big and in your face like the males. But there’s a whole lot of female-female competition. One female shows her interest in a male, the other females can’t let that go.”

The more he studies cowbirds, the more he’s coming to a view that some human males will undoubtedly find sobering.

“I’m starting to think it’s by the act of the female picking the male that the male becomes a good male,” he says. “That the female is really making the quality of the male for him.”

The temptation to see parallels between the behavior of Molothrus ater (brown-headed cowbird) and Homo sapiens can be irresistible for some of us. White has a slightly different perspective.

“Us animal behaviorists—we’re a weird group,” he says. “We really don’t look for the human connection as much as many people would expect us to. I think we look at humans and think about how cowbird-like some can be.” On the other hand, “there have been males and females long before there have been humans. So it stands to reason that there are going to be some generalities there.”

One is “this idea of the females coming in and being interested in the males, and all of a sudden stimulating the males’ aggressive behavior—you see that in humans all the time,” he allows. “Once a female’s involved, the rules of the game change no matter what game it may be.”

An old Jimmy Reed song comes to mind: “I’ll Change My Style.” If memory serves, it includes the line: “And if my lovin’ don’t please you,/ I’ll change that too.” It could be the theme song of the lovelorn male cowbird.

“Males are much more malleable than females,” says White, who has Buju Banton’s “Circumstances Made Me What I Am” playing on hismental iPod. “We had an experiment where we kept putting in males with interested females and changed the males, but as you moved the females around they didn’t change all that much. So they were the ones changing the males.”

There may be aspects of female behavior that are as malleable as their male counterparts’, he acknowledges. “We just don’t know how to find them. Right now, I don’t understand female cowbirds, frankly. Males are pretty much an open book, easy to read. Females are just tough. It’s all because of this subtle behavior. Males will tell you exactly how they’re feeling: big song, big display. The females stepping half an inch one way—that’s a big signal for them.”

Say you’re a stranger in town, and you have a foreign accent. For a man hoping to get lucky, that might or might not be a handicap. For cowbirds, it’s pretty much: Talk like the locals, or go home alone.

“Females have their preferences,” says White. “They have their song and the male has to fit that song to that preference.” His former colleagues at Indiana found this out unexpectedly, he explains. They put an Indiana male in with a female from Oklahoma, and assumed that, with time, the female would develop a preference for Indiana song.

“The experiment in that way was a spectacular failure, because by the end, all the males have Oklahoma song,” says White. “They change their song to be the variant for the female. The social-conformist male does whatever he has to do to make this female happy.” By such failures does science advance.

The male’s education, it turns out, hinges on a tiny movement of the female’s wing known as the wing-stroke. West and King soon determined that the male was changing his tune, but couldn’t figure out what was prompting him to change it. So they watched the interactions between the male and the female in slow motion, frame by frame.

“That’s the only way you can see this behavior,” says White, “but the behavior is a wing-stroke, and it’s a little 200-millisecond movement of the female’s wing in response to a song. And it’s very interesting to the male.

“It could be that this is the way females are actually selecting a male,” he adds. “They’re selecting an attentive, good male that can read a female.”

The equivalent of a good listener? “Exactly. And this is why females generally stay away from juvenile males—they’re as likely to peck at you or jump on you as to sing to you. And that typically is a big turnoff to females.” Adult males, or the more perceptive juveniles, will “take a little step, give a little whistle, give a little song, take a little step, and eventually get right in close.”

And that’s where the real action is. “The song of the male is fundamentally different hearing it at one foot versus anywhere greater than one foot,” White explains. “The sound and the notes attenuate very dramatically, and you have to be very close to the female to get her to go into the posture. Because it’s those first notes that really stimulate her to go into that posture.

“So for a male, he’s got to learn that if he wants to get copulation, he’s got to get very close to the female. That’s a simple thing, but it was really hard to realize because what you’re measuring there is the absence of behavior of the female. Females sitting there looking bored is a huge cue to these males.”

Selfish Jeanne isn’t the best looking female I’ve ever seen. Her feathers are faded, her insides are buggy, and one wing dangles precariously from her torso, courtesy of some over-sexed males. White named her after Richard Dawkins’ gene-centered view of evolution, but she’s really given herself up for science. She sits on a perch, dead and stuffed for three years, and she now has a plastic pole inside her that controls the movement of her wing and head.

“I Frankensteined her up a little bit,” says White, who points to the control system: a Lego base powered by a stack of AA batteries. “It’s not what engineers typically use,” he admits. “But it’s built for a 12-year-old, so it’s perfect for me.”

White and his colleagues have figured out how to make her do a wing-stroke, and apparently, that’s all a red-blooded cowbird male needs—buggy insides and all.

“What I’m trying to do is get to the mechanism point, to have control over one side of the equation,” he says. “Females first, because males are dumber than females and they’ll fall for the robot females much more likely than a female’s going to fall for another robot female or a robot male. Plus, the females don’t do much, so it’s easier to make a model that doesn’t do much than to make a big, singing male robot. And with the wing-stroke, I can start to—hopefully—shape his song.”

A microphone inside Selfish Jeanne will pick up a male’s song, he explains. “The song will be captured by computer and compared to a template of a particular song structure. If the song that’s sung is a close match to the template song, she wing-strokes. If it isn’t, she doesn’t. Theoretically I should get him to sing something ridiculous by shaping him with the wing-stroke. If that works I’ll have a paper called ‘Flipping the Bird.’

“The problem is the males fall for it a little too easily,” he sighs. “They copulated her wing off the last time I tried it.”

Song preference is a tangled skein that has to be teased out, one thread at a time. Which pretty much describes the arc of White’s research.

“Give the birds options—social options, space options, let them choose, let them show us the important things,” he says. “The history of this research is us trying to come up with the important thing and see if the birds find it important. And lo and behold, what we find is important is not what the animals find important. So the task here has been to figure out what the birds think is important.”

We have a copulation! B2M and B0B, over in the corner! Or so White tells me. He’s tuned in to sounds and sights that I miss completely. In my defense, most birds give new meaning to the word quickie. There’s no real penetration or anything; the female just unfans her tail while the male hops onto her back or gets close; they touch cloacas—the cloacal kiss, it’s called—and sperm moves from male to female. Check your watch and you’ll miss the whole magic moment.

“Hear the little rattle the female is giving there?” says White. “Some females do it a lot; some females never do it. There doesn’t seem to be any pattern of when they do it. Sometimes it’s to bring their male over. If their male has strayed far away, they’ll give a little rattle and he’ll come running.

“Sometimes I swear it’s just to get the male in trouble,” he grins. “She’ll bring him over to an area where there’s another male, rattle and bring him in all excited—then leave him with that other male.”

Just as we’re about to leave, White sees something that gladdens his heart. It’s Mr. Lonelyhearts, taking a deep breath and puffing up his chest.

“Here’s our widowed male again, starting off with a female,” says White. “He’s really turning it around today. He’s fixing himself up and getting out again.”