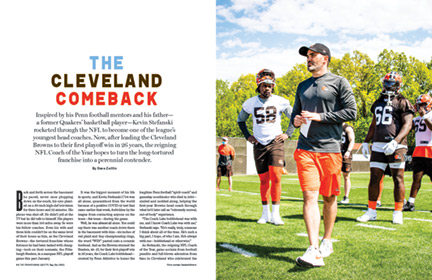

Inspired by his Penn football mentors and his father—a former Quakers’ basketball player—Kevin Stefanski rocketed through the NFL to become one of the league’s youngest head coaches. Now, after leading the Cleveland Browns to their first playoff win in 26 years, the reigning NFL Coach of the Year hopes to turn the long-tortured franchise into a perennial contender.

By Dave Zeitlin | Photo courtesy Cleveland Browns

Sidebar | The Glory and the Grind

Back and forth across the basement he paced, never once plopping down on the couch, his eyes planted on a 60-inch high-def television for three hours and 23 minutes. His phone was shut off. He didn’t yell at the TV but he did talk to himself. His players were more than 100 miles away. So were his fellow coaches. Even his wife and three kids couldn’t be on the same level of their house as him, as the Cleveland Browns—the tortured franchise whose fortunes he had been tasked with changing—took on their nemesis, the Pittsburgh Steelers, in a marquee NFL playoff game this past January.

It was the biggest moment of his life in sports, and Kevin Stefanski C’04 was all alone, quarantined from the world because of a positive COVID-19 test that came earlier that week, forbidden by the league from contacting anyone on the team—his team—during the game.

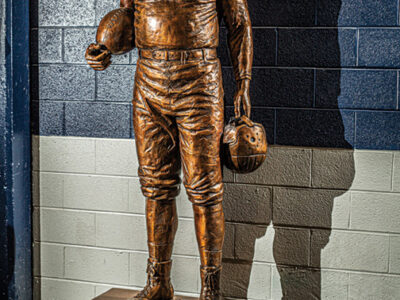

Well, he was almost all alone. You could say there was another coach down there in the basement with him—six inches of red plaid and tiny championship rings, the word “WIN” pasted onto a ceramic forehead. And as the Browns stunned the Steelers, 48–37, for their first playoff win in 26 years, the Coach Lake bobblehead—created by Penn Athletics to honor the longtime Penn football “spirit coach” and gameday coordinator who died in 2010—smiled and nodded along, helping the first-year Browns head coach through what he’d later call an “extremely surreal, out-of-body” experience.

“The Coach Lake bobblehead was with me, and I know Coach Lake was with me,” Stefanski says. “He’s really, truly, someone I think about all of the time. He’s such a big part, I hope, of who I am. He’s always with me—bobblehead or otherwise.”

As Stefanski, the reigning NFL Coach of the Year, gains acclaim from football pundits and full-blown adoration from fans in Cleveland who celebrated the playoff triumph over Pittsburgh like it was the Super Bowl, his ties to Penn remain strong. He texts often with Penn football head coach Ray Priore, his position coach when Stefanski patrolled the defensive backfield for the Quakers in the early 2000s. He remains good friends with many of his ex-teammates. Among his most prized keepsakes are a Penn football helmet and his first business card as Penn’s “assistant director of football operations”—a job created for him after he graduated by former head coach Al Bagnoli, another one of his mentors.

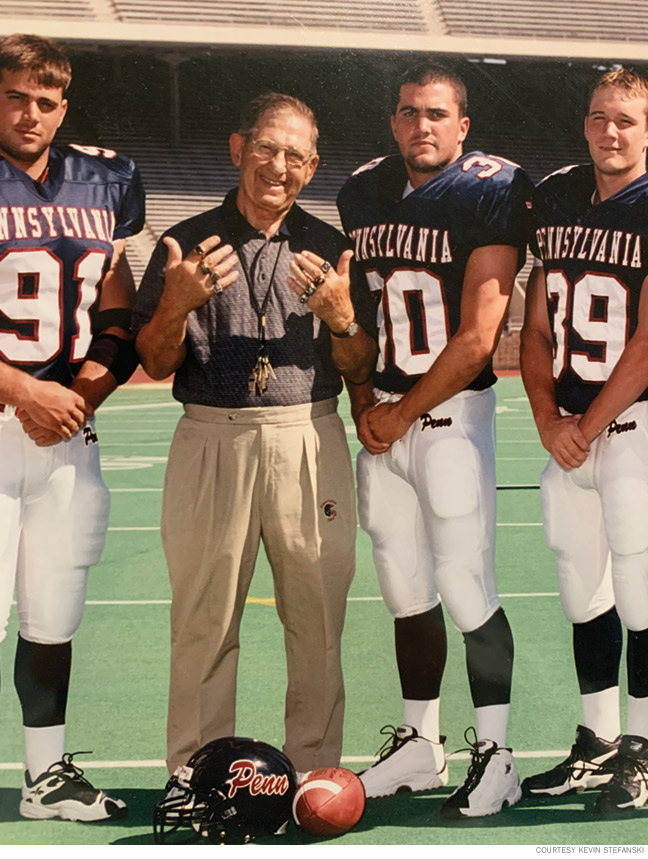

But nothing has helped him as much as the lessons imparted by Dan “Lake” Staffieri, best known for his bright clothing, quirky catch phrases, and endless positivity [“The Mascot in an Old Man’s Suit,” Jul|Aug 2010]. Once a regular assistant coach, Lake had morphed into more of a cheerleader by the time Stefanski arrived on campus in 2000: an almost 80-year-old former Marine hollering his esprit de corps chants in the middle of team huddles after practice. “DO BETTER THAN YOUR,” he’d yell three times, and the Penn players would respond “BEST” each time without missing a beat. “As I look back, I can reflect how important he is to the morale of a football team,” Stefanski says. “I think for a lot of us as young kids, it was hard because he was just an old guy in plaid pants and bowties saying these crazy things and you kind of got lost in the fun of it. But then you realize later how impactful it was in the moment—and then how impactful it’s been over the course of your lifetime.”

Known around the league as a humble, even-tempered coach with a high football IQ, Stefanski hasn’t brought Lake’s unique flair (or plaid clothes and bowtie) to Cleveland’s FirstEnergy Stadium. And Lake’s catchphrases likely wouldn’t work as well on millionaire professional athletes (though Stefanski’s own kids know to respond “Oh, very well” when their dad asks “How youuu doin’?”—another one of Lake’s trademark back-and-forths). But the spirit, the zeal, the resilience, the morale boosting that Lake brought to Franklin Field until his battered body could no longer handle it—well, that stayed with Stefanski as he shot up through the NFL ranks and especially now as he commands a locker room every day. “One of my main jobs is messaging,” the Browns head coach says. “What you say, your words, matter. While I may not use those slogans, I do think oftentimes about our team and our mindset and what we want to be thinking going into every week.”

So Priore wasn’t too surprised when, after the Browns were demolished by the Baltimore Ravens in Stefanski’s first game in charge last September, the Cleveland coach texted him the motto of resilience that Lake made popular at Penn. That same motto is scrawled on a piece of paper behind Stefanski’s desk in Cleveland—a handwritten note that Lake left in Stefanski’s locker almost 20 years ago when a crushing injury could have derailed his football journey:

Setbacks pave the way for comebacks.

Ed Stefanski W’76 remembers the play when his son tore his anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee. It was in Penn’s season opener against Lafayette in 2001, and “Kevin just ran out of bounds” before pulling up lame, recalls Ed, a former Penn men’s basketball player and longtime NBA executive. “Nobody touched him.”

On the face of it, the timing couldn’t have been worse for Stefanski, who was hoping to build off a strong freshman campaign in 2000 in which he was named the Quakers’ Defensive Rookie of the Year. But in another way, it turned out to be almost fortuitous, as the safety used that lost season to develop a lasting bond with Coach Lake, driving him around Locust Walk in a golf cart on Fridays so Lake could yell through a bullhorn and encourage students to come to games the next day. (Stefanski continued to be Lake’s driver even when he was healthy and suiting up, and his brother David Stefanski C’10 would later assume the role too.) And since he wasn’t able to practice, he began to more closely examine how the rest of the team’s coaches operated throughout the week, learning a different side of the game. “That probably was my first experience of what coaching felt like,” Stefanski says.

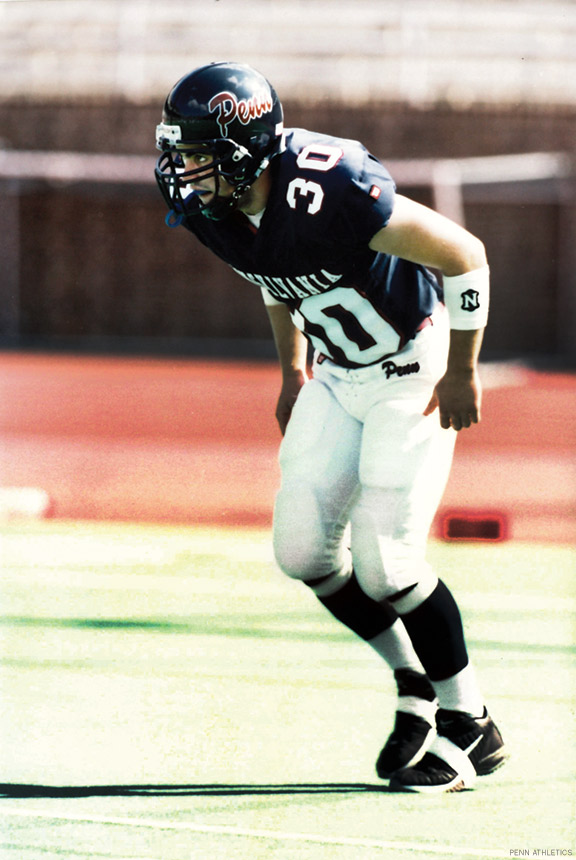

Even before that, Priore had noticed how adept Stefanski, a high school quarterback at St. Joe’s Prep, seemed to be at understanding complex schemes. “There are a lot of gifted, talented players out there,” Priore says. “But they play the game slow because they can’t process it. He played it fast.” As a freshman, Stefanski would sometimes wave off a play from Priore, then the defensive coordinator and defensive backs coach, as if to say, “yeah, I got it,” because he “already knew what the call was,” the Penn head coach recalls. “He just had that football mind.”

“I think about the 18-year-old version of me sitting in a position meeting for the first time in August, and Ray up on the chalkboard describing Cover 2 and Cover 3 and Cover 4,” Stefanski says. “It was eye-opening for me. And I ate it up. I loved it—absolutely loved it. … And it certainly started me on a path of loving the Xs and Os side of the game.”

In truth, the path had been laid before he got to Penn. Growing up with three brothers, it was “all sports, all the time in our house,” Ed says. “And you could tell he was sharp from the very beginning. Any time he played a sport, every coach was very complimentary, basically saying that Kevin was like a coach on the field.” Initially, it seemed like he might follow in his father’s footsteps and play basketball. “He thought he was Jason Kidd growing up,” Ed says. But when he figured out he wasn’t as good as the former NBA All-Star point guard, he hung up his basketball sneakers to focus on football.

The Stefanskis spent a lot of time at both the Palestra, where Ed played under Chuck Daly from 1973–76 and was later a color commentator for Big 5 games, and Franklin Field. They’d climb to the upper deck of the football stadium and sit on the opposing team’s side (“because the sun was on that side,” Ed says) and the boys would play with toys on the concrete between the aisles.

The allure of Franklin Field certainly played a role in Kevin’s decision to come to Penn. It also helped keep him there. After a strong junior campaign in 2002 in which he was named All-Ivy honorable mention as the Quakers swept through the league, Stefanski hurt his same knee in 2003, tearing his meniscus and missing most of the season. But he returned to play a fifth year in 2004 while plotting out his plans to remain in football after graduating. “I wanted him to get out of Penn because he was costing me a fortune,” quips Ed. “But listen, he followed his dreams.”

Ed should know. He spent more than 20 years in the mortgage banking business after graduating from Wharton, before switching gears to work in the front office of various NBA teams, beginning in 1999 with the New Jersey Nets [“Alumni Profiles,” Jan|Feb 2008]. He’s currently a senior executive with the Detroit Pistons following stints with the Memphis Grizzlies, Toronto Raptors, and his hometown Philadelphia 76ers.

Kevin’s path through professional sports has been different. Unlike his dad, a job in the business world didn’t stick; he worked in commercial real estate “for a hot minute” before realizing that wasn’t for him. Through a connection with James Urban, a longtime NFL assistant coach who used to serve as Penn’s director of football operations, he landed an internship with the Philadelphia Eagles during the team’s training camp in 2005. That’s when he caught the bug. “It was crystal clear to me that I wasn’t going back to commercial real estate—or the real world for that matter,” he says. Later that year he accepted a freshly created position to work on the Quakers’ staff, sitting side by side with his former coaches and “loving every minute of it.” The following year he was off to the Minnesota Vikings, where he remained for 14 seasons before moving to Cleveland.

“At no point in my life prior to getting into the NFL was I thinking I was going to be an NFL coach, let alone a head coach,” Stefanski says. “I was playing, and then all of a sudden, I couldn’t play anymore, so now what? I do think long and hard about those times at Penn and how they shaped me.”

Although Kevin has looked to his father’s career as inspiration, Ed has been equally inspired by how his son has navigated the professional sports world with such a level head—the same trait he first noticed some 30 years ago. “He doesn’t get too high and he doesn’t get too low,” Ed says. “And that’s a good trait when you have to manage a lot of personnel.” It’s also what helped Kevin remain on the Minnesota Vikings staff under three different head coaches, which Ed notes from firsthand experience is “very difficult in our business” since incoming coaches or general managers typically “want their own people.” Not only that, but he also took lessons from all of the coaches he served under while moving up the ladder: from assistant to the head coach, to assistant quarterbacks coach, to tight ends coach, to running backs coach, to quarterbacks coach, to offensive coordinator.

Despite having been a college defensive back, Stefanski proved to be a gifted offensive play-caller, and as the Vikings had some success he became a hot commodity around the NFL. In 2019 he was a finalist for the Browns head coaching position but lost out to Freddie Kitchens. When Kitchens was fired after just one season, Stefanski had a leg up at the beginning of another Browns coaching search, and was hired as Cleveland’s head coach on January 12, 2020, at the age of 37—which made him one of the youngest head coaches in the NFL.

Stefanski’s introductory press conference in Cleveland was “a very proud day for the entire family,” says Ed, who attended it along with Kevin’s mother, his three brothers, and his wife and their three children. The room laughed when Stefanski promised his kids a dog and a trip to Disney World because of the difficult move from Minnesota, and also when he had each media member tell him if they preferred the East Side or West Side of Cleveland before asking a question. But there was also an air of cynicism about whether Stefanski could actually be the one to change the fortunes of a franchise that had cycled through seven head coaches in the last decade and hadn’t made the playoffs since 2002. “With all due respect,” one reporter said, “we’ve heard many other coaches say the same thing, undeterred, coming in here very, very confident. What makes you different?”

All Stefanski could do was respond with typical coachspeak. “We’re not looking backward,” he said at the time. “We’re moving forward.” But he delivered on his promise by unlocking star young quarterback Baker Mayfield’s potential and making it clear to the team’s dynamic supporting cast that “personality is welcome [but] your production is required.” (He showed his own personality with playful jabs at tight end Stephen Carlson, a Princeton alum. “I think sometimes he must think I’m crazy because I’m taking shots at him at every turn.”) The result was an 11–5 regular-season record as Stefanski accomplished what the team’s previous nine head coaches could not in leading the Browns to the playoffs. Cleveland’s subsequent postseason win over the Steelers was its first since the franchise’s rebirth in 1999 (former owner Art Modell had controversially relocated the team, founded in 1945, to Baltimore in 1995), making Stefanski a runaway choice as the NFL AP Coach of the Year.

Now, with a young and exciting nucleus led by Mayfield, the Browns seem to be a legitimate Super Bowl contender for the 2021 season. And a fan base scarred by Modell’s betrayal and decades of losing just might have found an unlikely savior in a not-yet-40-year-old former Ivy League safety. “We’re focused on trying to do something special for these fans,” Stefanski says. “And I tell you what, it’s a unique fan base.”

Stefanski got a small taste of Cleveland’s passion for the Browns—which his father, a lifelong Eagles fan, insists is unmatched even by Philadelphians—but with COVID-19 limiting attendance in 2020 (among other pandemic measures that made his first season as head coach extra challenging, his own diagnosis included) he’s eager to see a full stadium this fall and winter. That includes the section in the bleachers known as the “Dawg Pound,” where fans wear outlandish costumes and yell for hours straight, embodying the city’s resilience and blue-collar identity—something Stefanski’s idol, Coach Lake, once knew something about.

“That Dawg Pound mentality has been passed down by many generations,” Stefanski says. “For me, I see it around town, I hear it around town. And now I’m looking forward to having a full experience and seeing what that feels like … what that sounds like.”

The Glory and the Grind

The former Penn football stars playing in the NFL have “have fed off each other.”

Greg Van Roten W’12 and Brandon Copeland W’13 have circled the date. October 10. The New York Jets versus the Atlanta Falcons. London, England.

If all goes to plan, it will mark the first time in their NFL careers that Van Roten, an offensive lineman for the Jets, will face off against Copeland, a Falcons linebacker.

“Every time I’m about to play Greg, I end up having an injury,” says Copeland, who signed with Atlanta in March. “God willing, this year is the year. I’ll make sure I tread lightly before that game in London.”

If the two line up opposite each other, it might feel like they’re looking into a mirror. Not only are they both Wharton graduates and former Penn football teammates, but they’ve also charted similar paths in the NFL, going from undrafted free agents to reliable veterans. And London, where games are occasionally held as part of the NFL International Series, would be a fitting place for them to meet, since their football journeys have taken them all over the map. “I think Cope and I have fed off each other,” Van Roten says. “And we’re lucky we have each other.”

Van Roten began to think the NFL was a possibility a decade ago after winning back-to-back Ivy League championships in 2009 and 2010 and earning first-team All-Ivy honors in 2010 and 2011. Looking through the 2012 draft class, “I was like, ‘I feel like I’m just as big as these guys and just as talented,’” he recalls. But it’s rare to make the jump from the Ivy League to the NFL, and Van Roten wasn’t selected in the 2012 NFL Draft. A homemade website and highlight tape caught the attention of the Jets and San Diego Chargers, who invited him to their rookie minicamps. He had to miss an accounting final and his Wharton graduation to attend both, but he didn’t make either team. His persistence paid off, however, when the Green Bay Packers signed him ahead of the 2012 season. “Being undrafted is difficult,” he says. “We’re not an afterthought but it feels pretty close to that sometimes.”

Van Roten played in 10 games for the Packers between 2012 and 2013 but was released in February of 2014. He was signed by the Seahawks but cut before the 2014 season, leaving him without a team and the realization that his pro football career could be over after just two years (especially when he worked out for the Vikings, who “went with a younger guy, even though I was 23.”)

The next year, he decided to play in the Canadian Football League (CFL), signing with the Toronto Argonauts. It was a culture shock. The pay wasn’t great, and neither were the facilities. And he had to quickly learn the different rules and nuances of the CFL game. “When I first got up there,” he says, “I was like, ‘Man, what am I doing? I’m in Canada. I don’t know anybody. It’s a different game.’ I was very homesick.” But he stuck it out for two years and played well enough that he received good offers to remain in the CFL in 2017. While pondering what to do next, he got a valuable piece of advice from a coach, who asked him, “Was your dream to play in the CFL your entire life?” Van Roten also followed closely as Copeland was making a living in the NFL, moving from the Tennessee Titans to the Detroit Lions [“The Optimistic Realist,” Nov|Dec 2016]. “I was like, ‘I can get back because he’s still doing it,’” Van Roten says.

So at 27, he returned to the US and got a workout with the Buffalo Bills (who signed someone else at his position instead) and then the Carolina Panthers. Recognizing that if the Panthers didn’t sign him “it probably wasn’t going to happen” at all, the former Ivy League and CFL lineman surprised a lot of people by making Carolina’s opening day roster. “Who is Greg Van Roten and how in the heck did he make the Panthers?” blared a headline in the September 4, 2017, edition of the Charlotte Observer. “My mom says I’m tenacious—a dog that latches on and doesn’t let go,” Van Roten explained in that same Observer article. “I like to prove people wrong, and that’s pretty much been my M.O. my entire football career.” He continued to surprise people by ascending to the starting left guard position, starting every game in 2018 and the first 11 of 2019 before a turf toe injury sidelined him.

After a strange free agency period at the beginning of the pandemic, Van Roten signed a three-year contract with the Jets—the Long Island native’s favorite team growing up—but again spent some time on the injured reserve list last season.

Injuries have also made Copeland’s NFL journey more challenging. He tore his pectoral muscle with the Lions in 2017 and with the New England Patriots last October, causing him to miss the second half of the 2020 season. (Between stints with the Lions and Patriots, he played for the New York Jets for two years, just missing out on being teammates with Van Roten, who signed with the Jets the season after Copeland left.) Copeland called it an “honor” to play for a recent dynasty like the Patriots but had to move on this past offseason, inking a one-year contract with the Falcons—his sixth professional team, just like Van Roten.

“Greg set the blueprint for me,” says Copeland, who in Atlanta will be reunited with another former Penn football captain, Brian Griffin W’91, the Falcons’ director of coaching operations. “I’m a veteran now so I feel a little bit more comfortable with my place on the roster. But I’m still the guy that was cut and told he wasn’t good enough and who’s been hurt multiple times. So I understand how none of this stuff is promised.” The idea that an NFL team can cut you at any time was the foundation of the money-management advice he gives to teammates—which he developed into a financial literacy course he taught at Penn [“Professor Cope,” Jul|Aug 2019] and an online “Life 101” course open to anybody (life101.io).

Transforming into “Professor Cope” has been one of several off-the-field entrepreneurial endeavors for Copeland, which he hopes will set up him and his wife Taylor Copeland W’13 (whom he met on their first day at Penn) and their two-year-old son Bryson nicely once he retires from football. But the 30-year-old linebacker is not yet ready for that day to come. “Ultimately we understand this is a moment and an NFL career doesn’t last forever,” he says. “So we’ve got to make moves and move around and do what we need to do.” Van Roten, who at 31 now finds himself as one of the oldest and most experienced players on the Jets, agrees. “I love the game,” he says. “And I think that’s why you put up with how physically and mentally demanding it is as you get older and start a family and have kids.”

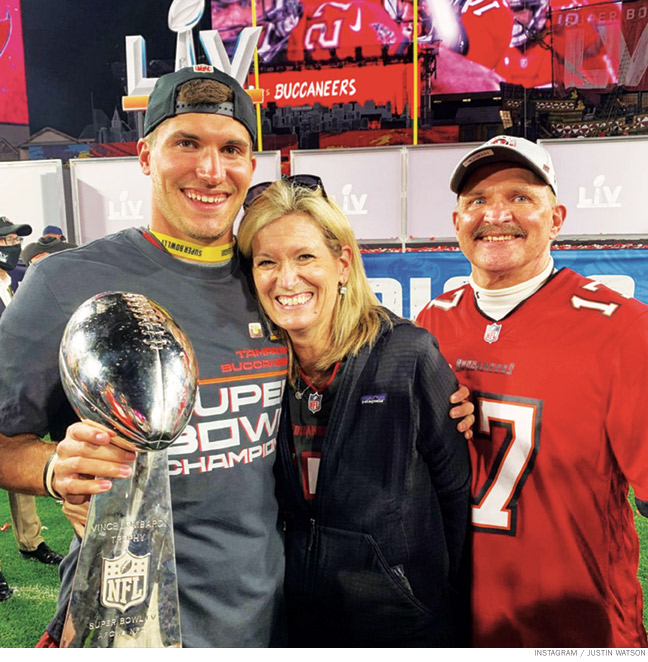

The ultimate goal, of course, is winning a Super Bowl—something Justin Watson W’18, the third Wharton alum playing in the NFL last season, accomplished in February with Tom Brady and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. “J-Wat, hoisting a trophy, that’s what we’re all doing it for,” Copeland says. One of the most accomplished wide receivers in Ivy League history, Watson was the second former Penn football player to win the title, after Jim Finn W’99 did it with the New York Giants in 2008. Though Watson didn’t make Tampa Bay’s gameday roster for the Super Bowl (and, more recently, had knee surgery in July, putting his 2021 season prospects in doubt), he “did help his team get to that point,” says Penn football coach Ray Priore. “And to be on that stage three years out of college is pretty awesome.”

“It’s pretty wild,” adds Van Roten. “It’s cool for a Penn guy to get drafted and win the Super Bowl and play with someone like Tom Brady. If one of us makes it, we all make it. That’s what it feels like.” —DZ