After the Kentucky Derby winner’s shocking injury in the second leg of the Triple Crown, his owners—alumni Roy and Gretchen Jackson—turned to Penn’s New Bolton Center to save their beloved horse’s life.

By Kathryn Levy Feldman | Photography by Sabina Louise Pierce

There is something about the outside of a horse

that is good for the inside of a man.

—Winston Churchill

Black Beauty. National Velvet. Seabiscuit. Secretariat.

Great horses are part of the collective American consciousness. In fiction and fact, we fall in love with their power, their stamina, their speed, and their hearts. And more than anything, we love to watch them run. Across open plains, down country lanes or around modern racetracks. There is little to match the raw excitement of thoroughbreds challenging each other at what they were born and bred to do.

Which is why, on the first Saturday in May, we were transfixed by the sight of one horse emerging from the pack of also-rans and winning the Kentucky Derby. For the next two weeks even those who didn’t know a filly from a foul ball wondered: Will this be the year? Will this be the one? Aren’t we due? After all, it’s been 28 years since Affirmed won the Triple Crown.

It seemed that all the ingredients were in place: An undefeated colt won the Derby by 6 1/2 lengths, the fifth-largest margin of victory ever, and had the pundits invoking Secretariat. The horse was bred and owned by 30-year veterans of the sport, highly respected in the industry, whose stable name, Lael, means loyalty in Gaelic; trained by a legendary equestrian (three-time gold-medalist in the Pan American Games, three-time Olympian and silver-medalist in the 1996 Atlanta games) who had also survived a plane crash, pulling three children to safety; and ridden by a jockey who knew in his heart and his hands that he was aboard a “special” mount. They were horse people in the truest sense, whose thoughts and actions rightfully centered on the horse—a magnificent, dignified beast who seemed to tolerate all the fuss because it came with the job he lived to pursue: running and winning.

Until it all fell apart, 100 yards into the Preakness, while we watched and wept for what should have been.

Today that horse—Barbaro, as anyone who reads a newspaper or watches television must know—holds court from a 12-by-13-feet hay-lined stall in the intensive-care unit of the George D. Widener Hospital for Large Animals at the School of Veterinary Medicine’s New Bolton Center. At press time, he continued to make an impressive recovery from the career-ending injury he suffered in the Preakness, May 20, at Pimlico Race Track in Baltimore. Ten days after 27 screws were inserted in the shattered canon, sesamoid, and long-pastern bones of his right hind leg, Barbaro’s progress was such that his surgeon, Dr. Dean Richardson, chief of surgery and Charles W. Raker Professor of Equine Surgery at Widener Hospital, was ready to amend his initial prognosis of a “50-50” chance for his patient’s survival. “I was going to call a news conference to say it’s officially 51 percent,” Richardson joked. “Seriously, every day that goes by is a big day.”

For Barbaro, certainly, and also for the horse’s owners, Roy Jackson C’61 and Gretchen Jackson CW’59 of nearby West Grove, Pennsylvania. The outpouring of public support—each day hundreds of cards, letters, flowers, balloons, religious medals, fruit baskets, stuffed animals, and bushels of carrots, apples, and peppermints arrive from people all over the world—has helped them deal with the “gamut of emotions from the euphoria of the Kentucky Derby to the devastation of the Preakness” and put to rest what might have been.

“You can either sit around and feel sorry for yourself or get along with life,” Roy muses. Three days after Barbaro’s surgery, Gretchen said, “It’s not about money, and it’s not about limelight. It’s more about the horse. And the beauty of it and the integrity … it does exist in horse racing.”

“All I ever wanted to do was ride horses and muck out stalls,” Gretchen says, noting that her sentiments haven’t changed much. “I’d rather see races than go to a cocktail party any day,” she says matter-of-factly.

Growing up near Bluebell, Pennsylvania, she began riding at the age of three, and got her first horse at 16, spending her summers at riding camp, perfecting the finer points of showmanship and jumping. She remembers reading about Whirlaway, the 1941 Triple Crown winner, and dreaming about the Kentucky Derby “ever since I was a little girl. [I] studied his photograph and loved it.”

Gretchen transferred to Penn in her sophomore year from Briarcliff Junior College, majoring in English. There she began dating a “good-looking” three-sport athlete named Roy Jackson she’d known from her high-school days at the Springside School in Chestnut Hill (the couple met at a subscription dance series held at The Merion Tribute House during their junior year). They married in 1959, settled on the Main Line and, as Gretchen puts it, “eased into horse ownership.”

Roy’s father, M. Roy Jackson C1899, died when Roy was eight, but the younger Jackson remembers his parents keeping pleasure horses and adds that his father, an avid foxhunter, is responsible for bringing a type of foxhound, the Penn-Marydel, to this country. Roy’s mother, Almira Rockefeller, and his stepfather, Hardie Scot L’34, got into the racing business in the 1950s. “I remember going to Atlantic City and watching the races,” Roy told The Blood Horse magazine in May. “I rode a bit as a kid, but all the boys stopped riding and started playing football while all the girls went on with horses.”

Gretchen still rides, and while their four children were growing up, she fox-hunted and “hung around with people who had race horses.” After living in Chester Springs and Paoli, the Jacksons bought their current property, a former dairy farm, in the late 1970s. Today, the bucolic—and extremely animal- and child-friendly—190-acre Lael Farm, just down the road from New Bolton Center, is home to 18 Jackson horses, all of which Gretchen feeds and checks every morning at 7:00.

The Jacksons are longtime supporters of Penn’s vet school, and Gretchen has been on the board of overseers since 2002. She’s also involved with Thoroughbred Charities of America and Anna House, a day-care center for children of backstretch employees at Belmont Park, and feels strongly about giving back to the sport. She describes herself as “deeply spiritual” and holds a master’s degree in pastoral counseling from Neumann College; she’s worked both at the YMCA in Wilmington and at Mirmont Treatment Center in Media, counseling children of alcoholics.

Roy’s athletic career at Penn was cut short by a potentially fatal heart condition discovered at the beginning of his sophomore year. (Surgery saved his life, but his resulting hospitalization delayed his graduation from 1959 to 1961. ) He channeled his love of sports into the sports business, first as a team owner and minor-league baseball executive starting in 1967, then as the head of his own sports agency, Convest, Inc., which he formed in 1983. He sold the agency in 2000 to devote himself full time to racing, a pastime Gretchen had selected back in the 1970s because she “figured it was something [they] could do together.”

The Jacksons entered the business as breeders, purchasing their first brood mare, Royal Sense, in the late 1970s.

Success in the racing business doesn’t come easily or quickly. It wasn’t until 1998 that things started to take off for the Jacksons’ racing operation, when Rashas Warning became their first significant winner, followed by a series of victories a year later with other horses.

Their European horse, Superstar Leo, was the champion juvenile in England and France in 2003. And on the morning of this year’s Kentucky Derby, the Jacksons, three of their children, spouses, and a full complement of grandchildren gathered in their hotel room to watch George Washington, a horse they bred, win the Stan James Two Thousand Guineas, a major race in England. “I don’t know how to explain two classic wins on the same day,” Roy said, after Barbaro won the Derby. “But we’re really enjoying it.”

The Jacksons divide the training duties for their American horses between Barclay Tagg, with whom Gretchen grew up, and Michael Matz—Barbaro’s trainer—whose home base of operation, the Fair Hill training center, is in close proximity to the Jacksons’ farm. They have 72 horses in various stages of training or breeding, plus another 16 racing. One of these, Showing Up, ran side by side with Barbaro along the backstretch of the Kentucky Derby, ultimately finishing sixth. “I have a picture in my mind of Barbaro and Showing Up running together up the backstretch—our colors running together,” Roy recalls.

The first rule of the horse business, as Gretchen remarked in a press conference three days after Barbaro’s surgery, “is not to fall in love with the animal because it’s so painful when something happens.”

Clearly, the Jacksons broke that rule with Barbaro—and apparently not for the first time. As The New York Times reported, they have also paid hefty medical bills for “a couple of older horses no one has heard of because they did not make it to the racetrack.” Dean Richardson elaborated on May 23: “I’ve known the Jacksons a long time. [Barbaro] could have absolutely no reproductive value and they would have saved this horse’s life.”

“We have an obligation, “ Roy told The New York Times. “We are their keepers.”

Long before he ever won a race, Barbaro began collecting admirers. The Times quoted John Stephens, at whose training center in Florida Barbaro learned the basics of being a racehorse, as saying, “[H]e was memorable because he was a big rangy colt with a great mind. Most horses that age don’t know when to use their energy … He was different. He was a natural.” Peter Brette, Matz’ assistant and a former champion jockey in Dubai, recalled the first time he got on Barbaro’s back. “He had perfect balance and perfect structure, and you could hardly feel him beneath you,” he said, according to the Times. “When they told me he was just a two-year old, it took my breath away.”

With Barbaro, Matz knew he had a “once in a lifetime” horse on his hands and planned a Triple Crown campaign that defied conventional wisdom, spacing Barbaro’s prep races a longer-than-normal five to eight weeks apart—with the Jacksons’ complete blessing. “Without a doubt, it was the simplest lead-up, without a wrinkle in the whole thing,” says Gretchen. “Everything just went according to what we hoped.” The horse never missed a day of training because of injury and by all accounts was incredibly fit both before and after his stunning victory in the Kentucky Derby. “When I led him into the Winner’s Circle at Churchill Downs, I was amazed that he wasn’t even wet; it was a trip in the park for him,” Gretchen says.

He was just as fit going into the Preakness, according to both the owners and trainer. Speculation about miscued gates, horses clipping heels at the start, and other conspiracy theories aside, Barbaro’s breakdown was, as Dr. Richardson told the Times, “a single, catastrophic misstep … an accident.”

Unfortunately, it is one that happens fairly frequently: about 1.5 times per 1,000 starts, according to David Nunamaker, a professor of orthopedic surgery at Penn and chairman of clinical studies at the New Bolton Center. “This is more dangerous than any sport you have heard of.” Part of that danger is inherent in a racehorse’s anatomy: Its four legs are relatively long and thin compared to the more than 1,000 pounds they typically support. When you combine anatomy with speeds of over 40 miles per hour over distances of more than a mile, bones break, missteps follow, and dreams shatter in the blink of an eye.

Jockey Edgar Prado is widely credited with pulling the horse up quickly, but not quickly enough to prevent Barbaro’s multiple fractures. Richardson credits the horse’s “tremendous athletic ability to pull up … literally gallop[ing] on three legs for a few strides” with “saving his life.”

There was never any doubt that Barbaro was going to New Bolton Center—or that Dean Richardson was going to perform the surgery, say the Jacksons. Richardson had treated some of their other horses over the years, and he considers himself “good friends” with Michael Matz. “It is fair to say that everyone at New Bolton was rooting for Barbaro to win the Triple Crown,” Richardson says, although none of the vets there had ever had a reason to see the horse. “In fact, I know the vet who takes care of Barbaro, and [the horse] was perfectly healthy prior to this injury,” he adds.

Richardson, who was in Florida at the time of the accident, had been watching the Preakness at a friend’s equine hospital, where he had just finished a surgery as the race was about to get under way. The TV set was small, “but you could see enough,” Richardson told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I knew it was a very bad injury.” When he looked at Barbaro’s digital x-ray, which was e-mailed to him within 30 minutes of the accident, “it was worse than I expected,” he added. “I tried to sleep, but didn’t succeed real well.”

Richardson flew back to Philadelphia the next morning. By then, Barbaro had been transported to New Bolton, where he spent a relatively peaceful night, even lying down for a couple of 45 minute naps, before being prepped for surgery.

Dr. Corinne R. Sweeney, the vet school’s associate dean for New Bolton Center, emphasized that while Barbaro is clearly a “celebrated” horse, “saving large animals is business as usual for us. This is what we do 24/7.”

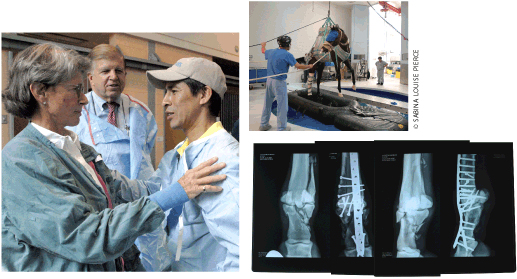

New Bolton’s Widener Hospital is one of the busiest veterinary clinics in the nation, treating more than 6,000 patients on site per year. Another 19,000 cases are seen by its field service. Facilities include the C. Mahlon Kline Orthopedic and Rehabilitation Center, where Richardson performed Barbaro’s five-hour surgery, and the unique recovery pool in which Barbaro safely emerged from anesthesia. Barbaro is recuperating in the Connelly Intensive Care Unit, which features climate-controlled stalls that are monitored from a central nursing station, as well as a monorail system to move patients from the recovery pool area or surgical suites.

New Bolton also has its own farrier shop, in which a special horseshoe that has been applied to Barbaro’s left hind foot—the good one—was designed and patented. “One of the complications that can occur following leg fractures in horses is the risk of developing laminitis [a potentially fatal hoof problem] in the opposite foot from bearing extra weight,” says farrier Rob Sigafoos. “To reduce the risk, we applied a supportive shoe to Barbaro’s left hind foot immediately following surgery.”

Richardson felt “fairly confident” that Barbaro would wake up from the surgery, but he didn’t know for sure until he felt the warmth of the animal’s foot and the strength of its pulse, which meant that his blood supply had been maintained. Another good sign was that the skin, while very badly bruised, hadn’t been broken, decreasing the chances for infection. But the operation was much more complicated than Richardson had expected, requiring a bone graft from the horse’s pelvis to replace pieces of the bone that had shattered.

“We ended up doing what we had planned; it was just harder than I’d hoped,” he told the Inquirer. He put in 27 screws and a 16-hole steel plate, inserting screws into some pieces “barely more than a centimeter wide.”

“It was a very, very difficult surgery,” Richardson explained after the operation. “But to be honest, I would have worked that hard on the same case if it were a $5,000 gelding.” (In fact, Richardson had performed a plate-and-fusion of a fetlock, one procedure he used in Barbaro’s surgery, on just this type of horse a few weeks before; the horse went home from New Bolton a day after Barbaro’s surgery.) When he was asked at a May 30 press conference if it took “courage” for him to perform the surgery on what might be construed a “hopeless” case, Richardson replied, “Clearly it’s not courageous to do your job.”

Richardson is regarded as a leading international expert on equine fractures, and has performed more than his fair share of complicated reconstructions. “Dean is such a perfectionist that he may tell you that he never performed this exact surgery before, but he and others have fixed many permutations of fractures as complicated as Barbaro’s,” says Sweeney.

“We don’t get the opportunity to see as many of these complicated orthopedic cases as human trauma doctors do,” Richardson explains. “And yes, money is a factor but there are a lot of people who do this because they love their horses.”

It’s a sentiment he discovered for himself as a college freshman at Dartmouth, when he took a riding class to fulfill the physical education requirement—and was instantly smitten. The would-be actor switched his major to biology and began contemplating a career that would involve horses. “To be fair, I also learned I wasn’t a very good actor,” he adds with a laugh. Following graduation, he took a technician job with an equine hospital in Southern Pines, North Carolina, and then enrolled in vet school at Ohio State, where he met his future wife, a small-animal veterinarian. He returned to New Bolton in 1979 for his internship and has been there ever since. Richardson still rides, plays basketball once a week, and is a “competitive” golfer. He is also a dedicated teacher. “I am sure Dr. Richardson did not miss one teaching moment during Barbaro’s surgery,” says Sweeney. “We will all be learning from Barbaro, just like we learn from every one of our patients.”

At the moment, Barbaro is proving to be a model patient, which has helped his recuperation. “This is a classy, well-behaved colt who literally doesn’t do anything wrong,” Richardson says in an interview two weeks after Barbaro’s surgery. “He’s doing great right now—better than I could have possibly hoped.” Barbaro was completely off antibiotics, receiving minimum levels of painkillers, and “tolerating things very well.” The Jacksons visit every day, donning sterile booties and gowns each time they enter his stall, and a retinue of caregivers attend to his every need. “Horses adapt remarkably well to living in a stall,” Richardson says. “He gets groomed, massaged, bathed, and plenty of TLC.”

Although the situation could change at any time, if all continues to go well, Richardson expects Barbaro to be in the hospital for two-to-three months, eventually going outside and walking on a lead. “We’re shooting for him to be turned out in a field,” he says.

The Jacksons’ goal for Barbaro is for him to lead a “pain-free life,” regardless of whether or not that includes a career as a stallion. “It would be a dream come true to see little Barbaros, but for us, pain-free is enough,” Gretchen says. “He could live on our farm and eat grass for the rest of his life, and that would be fine.” And how will she know his physical status? “You can tell how a horse feels by the way he carries himself and by looking into his eyes,” she explains. “I will know. It’s one of the gifts animals give us.”

Another, of course, is the memory of perfection—that striking snapshot of the Jacksons’ blue and green colors striding side by side, with one set ultimately pulling away. “To get one [horse] to the Kentucky Derby is enough, but to have two of them run is amazing. It was a wonderful experience,” says Roy. “A lifetime dream,” concurs Gretchen. “He is the best horse we ever had and raced. He’s striking, and he’s also sensible. He’s always done the right thing at the right time.”

Certainly Barbaro’s legions of fans continue to hope his recovery will be swift. Asked why they think their horse has captured the attention of the world, Gretchen attributes it to the human penchant of being “hungry for a hero.” Richardson has another take: “This horse gave his all, and his owners are doing their all to save his life.”

Kathryn Levy Feldman is a freelance writer based in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Her article, “Saving Bentley” [July/Aug 2003], also dealt with the vet school’s work. For continuing medical updates, to send Barbaro a message, or to contribute to the Barbaro Fund to improve equipment and services at New Bolton, visit (www.vet.upenn.edu).