Knighted by Britain for his work as the Allies’ “railroad czar” in World War I, the Penn alumnus and Pennsylvania Railroad veteran went on to remake the Canadian National Railways before the Great Depression, poor health, and scandal brought him low.

By Dennis Drabelle | Illustration by John Tomac

“ENGLAND MAY LOSE SUPERMAN,” warned a 1922 British newspaper headline about Henry Worth Thornton C1894 Hon1923. Four decades later, historian J. Plomer summed up Thornton’s reputation in The Railway and Locomotive Society Bulletin. He was “not only a great railroader, but an international figure with a unique and dramatic career, personally venerated and loved, probably, by more people than any other person in the history of commerce and transportation in the English-speaking world.”

Some of Thornton’s distinctions came courtesy of Penn: class president in his freshman year, recipient of an honorary doctorate in 1923. Eight years later, his name was the second to be engraved on the since-retired Guggenheim Cup, celebrating alumni who “honored the University most by notable success in any walk of life.” The tribute situated Thornton between the first Guggenheim honoree, the eminent scholar of Elizabethan literature and longtime Penn faculty member Felix E. Schelling C1881, and the soon-to-be-third, Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts C1895 L1898 [“The Justice Who Was of Two Minds,” Nov|Dec 2009].

Thornton attained his most glittering honor in 1919, when, after he became a naturalized British citizen, a royal sword-tap on the shoulder transformed him into a knight of the British empire—a reward for his brilliant work as the Allies’ World War I railroad czar. He was also inducted into the French Legion of Honor and the Belgian Order of Leopold, making him the toast of four countries—the United States, Great Britain, France, and Belgium—with a fifth, Canada, soon to come.

A dozen years after his ennoblement, however, Sir Henry’s reputation was plummeting and his health was shot. Like many another swaggering businessman in the heady 1920s, he’d run afoul of the Great Depression, but in his case there was more: character flaws that justified the title of his biography, The Tragedy of Henry Thornton.

Born in 1871, Thornton grew up in Logansport, Indiana, where seven lines of the Pennsylvania Railroad, familiarly known as the Pennsy, converged. Railroad ties, if you will, may have been what first drew young Henry and James Alexander McCrea to each other when they were prep-school students at St. Paul’s in Concord, New Hampshire—at the time McCrea’s father was a Pennsy vice president. At any rate, the boys struck up what became a lifelong friendship.

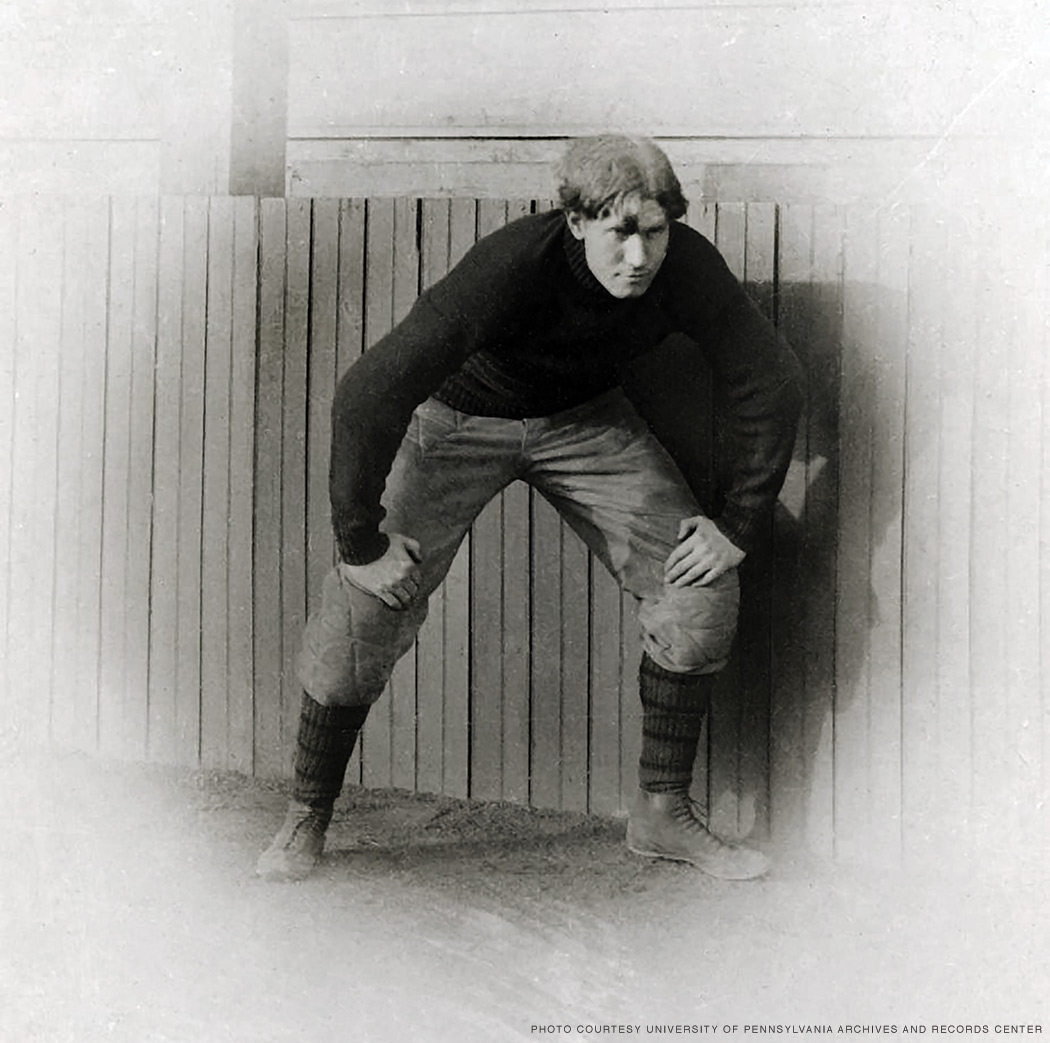

At Penn, Thornton’s brawny build and height of six foot three made him prime gridiron material; the Pennsylvania Gazette issue of October 13, 1922, identified him as “a member of the famous ’92 and ’93 championship football teams, playing guard.” Football meant so much to Thornton that after graduation he coached Vanderbilt’s team for a year, compiling a 7–1 record. On entering the business world, fittingly enough he caught on with the Pennsy, starting, as the New York Times noted years later, “on the lowest rung of the ladder.” He climbed that ladder to become Engineer of Maintenance of the Way at age 28; two years after that, he was made a division superintendent.

The Pennsy expanded into New York City (hence Penn Station), where its subsidiary the Long Island Railway grew into what was probably the largest suburban passenger carrier in the United States. James Alexander McCrea, Thornton’s chum from St. Paul’s, was now the Long Island’s general superintendent and in need of an assistant. McCrea got Thornton transferred into the slot, and in 1911, at age 40, the right-hand man succeeded the boss as general superintendent.

Thornton held that job until 1914, when a committee representing the Great Eastern Railway of England visited the United States to recruit an American as the firm’s general manager. They found their way to Thornton, a choice explained 30 years later by John Walker Barriger, president of the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railway, in an address to a society of railroad buffs: “[Thornton’s] magnetic personality, ease of manner, and fluency of speech [had already] brought him public recognition to a degree seldom gained by a railroad officer below the highest rank.” Thornton, his wife, the former Virginia Blair, and their two children duly moved to England.

Putting an American in charge of the Great Eastern rankled with some Britons, especially after the railroad’s chairman tactlessly said to a reporter, “There is no man in England big enough for this job; here is the man who will do it!” But the Great Eastern was in part a suburban railroad, and Thornton’s experience with the Long Island served him well—until the First World War broke out a few months later and, in Barriger’s words, “The exigencies of the struggle dissolved personalities and united all for King and Country.”

Thornton climbed the wartime British railroad ladder until he was a major general in the army responsible for the transportation of men, materiel, and supplies in coordination with French and Belgian colleagues. His biographer, Canadian journalist D’Arcy Marsh, argued that Thornton and his fellow railroaders’ contribution to the Allied victory was too often slighted. “Had they not brought into existence, overnight, a system which made it possible for the troop train southbound from Victoria Station to synchronize, even to the matter of seconds, with the convoyed troopship and the train that met it at Calais—the tide might have turned at the Marne, and the [German army] might have marched through Paris.”

Thornton returned to the Great Eastern when the war ended in 1918, but four years later the rumored departure of England’s superman came to pass. The Great Eastern was merging with two other firms, and Sir Henry was so miffed at not being named the new entity’s general manager that he quit. A timely offer came his way: the presidency of the government-owned Canadian National Railways. After meeting with Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King, who assured him there would be no political interference in his work, Thornton accepted the job, which came with the handsome annual salary of $50,000 Canadian, the same as his counterpart’s at the CN’s privately owned rival, the Canadian Pacific.

Thornton may or may not have heard the nickname applied to the Canadian National by its detractors: “Canada’s white elephant.” But he knew what a daunting task he’d taken on—looking back years later, he admitted to relishing “a good fight [and] here was certainly the place to have it.” The CN was an amalgamation of several predecessors, which Marsh described as “joined together in name, [but] the marriage, as it were, had never been consummated.” Thornton’s remit included giving the stitched-together firm a common identity, publicizing it, cutting fat, repairing old lines, investing in new ones, and extending service to some of the remote stretches of Canada, a country “not yet … out of the pioneer stage.” All this was to be done in competition with the Canadian Pacific, something of a legend in that its transcontinental reach had helped bring British Columbia into the federation half a century earlier, thereby giving Canada the sea-to-shining sea breadth of its neighbor to the south.

Thornton got started by touring much of the CN’s extent—22,000 miles in all—and delivering countless pep talks. Looking back on that period, he explained that “in the last analysis the real thing I have done to make the Canadian National Railways a success is to pound, pound, pound, until it is now second nature with the employees to understand that a messenger boy is as important in his sphere as I am in mine, and that the minute a single man slacks on the job a bolt begins to rattle.”

One of Thornton’s most endearing and useful traits was his rapport with ordinary workers; before leaving England, he’d been presented with a badge making him an honorary member of the Railwaymen’s Union, a token that he wore on his watch-chain for the rest of his life. In Canada, he enhanced his appeal to employees by hanging out with them after hours. “I … leave the house about midnight and go down in the yards for a yarn with the men,” he told a visiting American journalist. “It’s quiet then. I like it.” His cultivation of workers went a long way toward blunting their reaction to the 9,000 jobs—about eight percent of the total workforce—that he eliminated. So effective was Thornton’s administration that at the end of the decade the CN’s annual earnings peaked at $17 million. As Marsh observed, “The White Elephant was no more.”

Thornton brought attention to the company by exploiting the new medium of radio. “Equipment for transmitting programs was installed in passage lounges, stations, and hotels,” writes historian T. D. Regehr in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry on Thornton, “and in 1923, using the best available technology, the company created North America’s first radio network.” The CN sponsored Sunday afternoon broadcasts of concerts by the Toronto Symphony and other programs. Thornton also had radios installed in CN trains, and he himself went on the air to deliver annual Christmas messages to his employees; thanks to these and other “appearances,” his voice became one of the most recognizable in Canada. The CN eventually sold its radio network to the government, and it evolved into today’s Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Under Thornton’s leadership, the CN built its own hotels to compete with the Chateau Lake Louise and other Canadian Pacific Railways hostelries in Banff and Jasper national parks. His most dramatic implementation of the policy to knit Canada’s far-flung parts into a whole was the CN’s takeover of a new line from Saskatchewan to Fort Churchill, Manitoba, on Hudson Bay. In Marsh’s view, this was “one of the great stories of Canadian development,” not least because it lessened the domination of the country by its eastern provinces. Under Thornton, the CN became a showcase for the principle of government ownership.

Such an unbroken string of triumphs can instill hubris, and Sir Henry was not immune. One telling instance reported by Marsh took place on a Jasper golf course. Thornton’s ball “had landed in a clump of trees and his position was hopeless; so hemmed in with timber was he that it looked as if he would have either to pick up [the ball] or lose heaven knew how many strokes ploughing his way out. Other players had stopped, curious as to what he would do.” Reasoning that not for nothing was he president of the CN, Thornton conferred with his caddy. “The boy put down his bag and started off for the club house at the double. Presently he came running back with two men following him, carrying a crosscut saw. … A few minutes later … there was one less tree at Jasper, but the President won his hole.”

More troublesome was Thornton’s marital record. He and Virginia divorced because of what they thought of as incompatibility, but which, to satisfy the laws of Pennsylvania, where they had married, had to wear the prurient label “indignities to the person.” The scandal was exacerbated by Thornton’s remarriage, a little over a month later, to a Bryn Mawr graduate named Martha Watriss, who, at age 28, was 27 years his junior. The term “trophy wife” had yet to be coined, but that’s how people tended to perceive the second Lady Thornton.

Nonetheless Sir Henry’s star was still in the ascendant. On a 1928 European trip, he acted as an unofficial Canadian ambassador, especially in Scandinavia, where there was a widespread feeling that Canada had lured immigrants from the region with misleading hype and then done little or nothing to help them get settled. In one speech after another, Thornton almost singlehandedly repaired relations—an accomplishment that Marsh calls “the zenith of his career.” With regard to immigration generally, however, Sir Henry unfortunately reflected the prejudices of his time. Speaking at a luncheon in New York in 1924, he declared, “We demand only that the immigrant possess five qualifications: sound mind and body, a willingness to live under our traditions—for we want no communists—an ability to earn a living with the help we offer, and that he be a Caucasian. Canada cannot afford to create for herself a racial or negro problem.”

Back in Montreal, where the CN was headquartered, the Thorntons entertained lavishly. He deemed this a necessity of his job and made little distinction between company funds and his salary; more than once he found himself on the verge of bankruptcy. The Depression hit both him and the railway hard, and so did the change of government wrought by the national elections of 1930. Two years before American voters were to vote the Republicans out of office for failing to anticipate the stock market crash or take effective action to ameliorate its effects, Canadians showed the way—except that the politics were in a sense reversed. Out went Canada’s incumbent Liberal Party, and in came the Conservatives. Former prime minister Mackenzie King’s pledge against political interference with the CN was now inoperative.

Thornton’s enemies had been lying in wait. In furtherance of what Marsh called “a plot to discredit Sir Henry in the eyes of his associates, his employees and the country,” in June of 1931 the House of Commons Railroad Committee summoned him to testify. A sly MP named Peter McGibbon said he was being peppered with complaints from his constituents, who viewed the CN’s executives’ salaries as excessive and the company itself as “a fertile field for graft.” Challenged by a member friendly to the CN, McGibbon retracted his “fertile field for graft” slur, but the damage had been done. Newspapers across the country picked up the phrase, which the persisting hard times made more damning.

Thornton, meanwhile, was angling for the CN to acquire Cook’s Tours, a global travel agency that he expected to bring tourists to Canada in droves. But his grandiose plan fizzled, and the Conservative inquisition carried on, flyspecking expenses present and past and slamming the railroad’s luxury hotel in Jasper as wretched excess—never mind the many tourists it drew or the money they pumped into the Canadian economy. There was talk of a merger between the CN and the Canadian Pacific, or at least government-imposed cooperation. The fight seemed to have gone out of Thornton, who after several days in the hot seat suggested that a commission be appointed to investigate his and the CN’s performances.

He got what he asked for, and the Duff Commission, so-called after its chairman, Justice Lyman Duff, set out on a tour of CN holdings. One issue it examined was duplication of routes by the CN and the Canadian Pacific. A notorious example came to light in British Columbia, where the two railroads ran parallel for miles on either side of the Fraser River. Then came a bridge on which the Canadian Pacific train crossed the river, and it seemed as if the sensible thing would finally happen: the two lines would fuse. But the next time a Canadian Pacific passenger looked out the window, there was the CN train, which had crossed to the other side, too, as if neither railroad wanted to be caught fraternizing. This certainly seemed wasteful, but one of Thornton’s subordinates combed the CN’s routes and discovered that only a quarter of them duplicated the Canadian Pacific’s—hardly surprising given the CN’s multiple ancestry.

By then Henry Thornton had been diagnosed with cancer. Before the Duff Commission finished its work, he issued a statement in which he reminded his critics that every expense now being second-guessed had won governmental approval when originally submitted—in short, he was being judged by a double standard. Nevertheless, he continued, “I … feel that the successful operation of this enterprise can only be carried on if the country as a whole is heartily behind the management.” He handed in his resignation, effective August 1, 1932. Before leaving Montreal by train, he listened to a panegyric from the station manager and responded, “Tell the boys that I’m sorry I couldn’t say goodbye to them all. Tell them …” At that point, Thornton’s emotions got the better of him, and he couldn’t go on.

He was stripped of his pension but given $125,000 in severance pay. He looked to India for a possible job as head of a commission empowered to take a comprehensive look at that nation’s railways, but it didn’t pan out. He and Martha settled in New York City, where his condition worsened. The CN’s unions were planning a gala dinner for him in Montreal—meant to be, in Marsh’s words, “the most eloquent testimonial ever tendered an industrial executive by the labouring millions of North America”—but before it could take place, Sir Henry died on March 14, 1933, at age 61.

In a diary entry, Mackenzie King had mused darkly on Sir Henry’s downfall. “Thornton has himself to blame … of late his bad habits have got the better of him and destroyed his judgment. Had he possessed a Christian faith & lived by it he would have been one of the greatest of men. As it is he is now a colossus fallen.” (That allusion to Thornton’s religion probably had to do with his divorce and quick remarriage.)

Marsh took a more nuanced view: late in Thornton’s tenure at the CN, he had become a whipping boy for Canadians’ outrage over the stock market crash and the ensuing hard times. But Marsh also pointed to a dichotomy in Sir Henry’s character: “He had never been an acquisitive man—that was the ironic aspect of his defeat—but he had developed an insatiable appetite for the spending of money, as a form of self-assertion.”

The Canadian National and the Canadian Pacific never merged. The CN remained publicly owned until 1995, when it was privatized. Today the CN is the largest railroad in Canada—a posthumous tribute to Henry Thornton, without whose stewardship in the 1920s the CN might not have survived.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Power of Scenery: Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origin of National Parks.