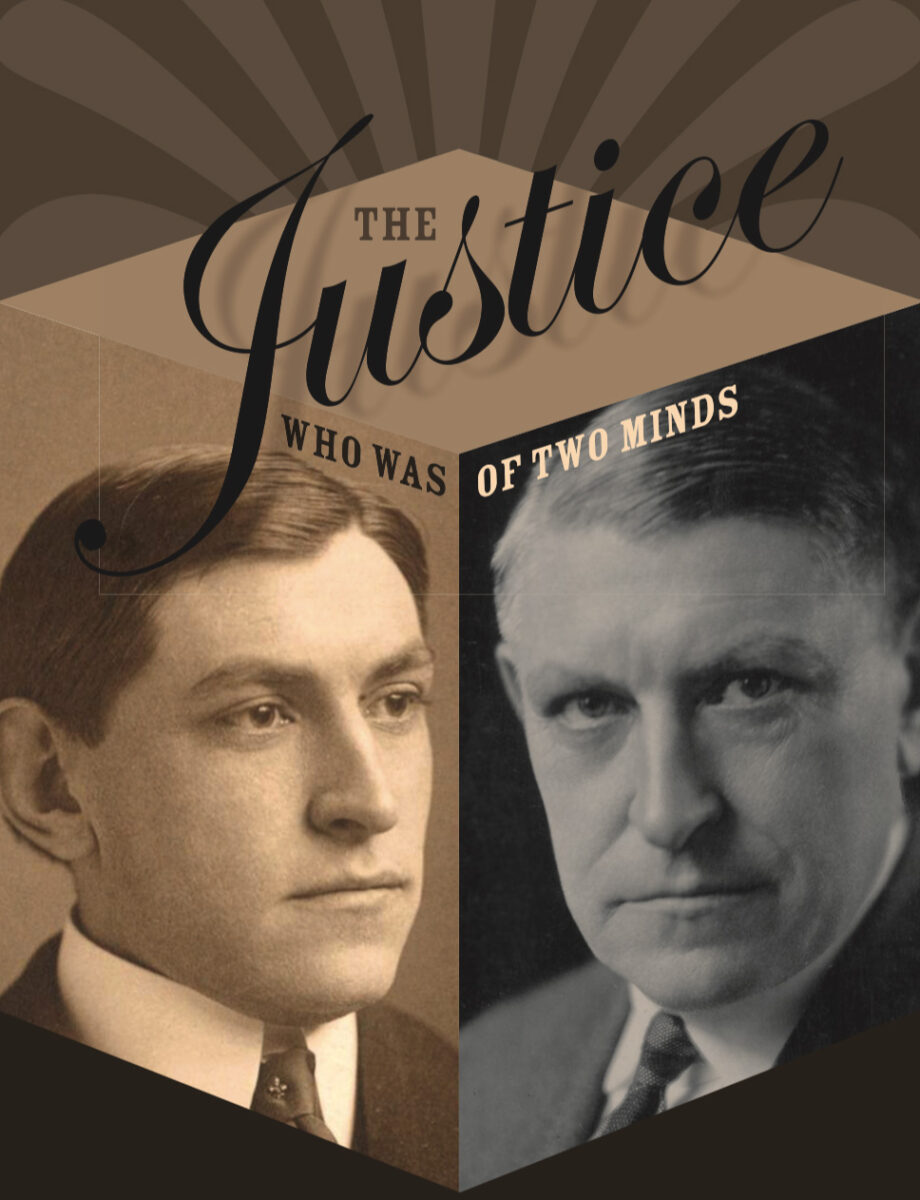

Appointed to the Supreme Court for his crusading prosecution of the Teapot Dome Scandal in the 1920s, Owen Roberts went from New Deal obstructionist to enabler after Roosevelt threatened to “pack” the court. Was the alumnus and future Law School dean merely expedient, or a statesman who put country before consistency?

By Dennis Drabelle | Photos courtesy Penn Archives

Before Rod Blagojevich or Jack Abramoff, before Nixon approved that second-rate burglary or Bill met Monica, there was the Teapot Dome scandal of the 1920s. Though far from the most lucrative or juiciest case of government wrongdoing, it does stand out in one respect: When it comes to building federal cases, few can match the standard set by Teapot Dome special prosecutor Owen J. Roberts C1895 L1898.

Roberts worked for five years to expose a group of crooks that included a member of the president’s cabinet, going so far as to pay his own expenses to keep the investigation alive when Congress was late in funding it. Largely on the strength of his Teapot Dome performance, Roberts was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1930.

A few years later, however, most Americans held a quite different view of Roberts: He was he one of the “nine old men” obstructing the New Deal. And then he made the “switch in time that saved nine”—a reference to Roberts’s perceived move toward the judicial Left when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, frustrated by the high court’s repeatedly thwarting his legislative efforts to combat the Great Depression, tried to “pack” it with new justices who could be counted on to vote his way. In joining with liberal colleagues to uphold the constitutionality of several New Deal programs—thus reducing the urgency to remodel the court—Roberts is assumed to have saluted the president.

It hasn’t been easy to square these contrasting images of Roberts as a vigorous, improvising prosecutor on the one hand, and a drifting, expediency-minded judge on the other. However, a pair of recent books, focusing on the Teapot Dome scandal and on the court-packing scheme, suggest that in both instances Roberts acted as a statesman. Although the famous switch was not a direct response to Roosevelt’s attempt to remake the court, it looks like a calculated maneuver by a man less concerned about his own consistency than about the future of his country.

Owen Josephus Roberts (1875-1955) was every inch a Penn man. As an undergraduate, the Germantown native was editor of The Daily Pennsylvanian—and that was only the most visible of his extracurricular activities. As Burt Solomon writes in his excellent account of the court-packing episode, FDR v. the Constitution, the list of Roberts’s undergraduate doings “fell a single word short of the longest yearbook caption for any member of his eighty-man class.” After graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1895, Roberts went over to the Law School, from which he graduated three years later with highest honors. For the better part of the next two decades he maintained a private practice; founded the Philadelphia firm now known as Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads; and taught at the Law School, where he was made a full professor in 1907. Late in his career, after leaving the bench, he returned to serve as dean (for $1 a year) and taught a course in constitutional law. The school’s annual Owen J. Roberts Lecture perpetuates the bond between the man and the institution.

Roberts was a Republican, but not an overly partisan one. In going after the corrupt exploiters of Teapot Dome, a federal petroleum reserve in Wyoming which got its name from the odd-looking rock formation on top of it, he paid no attention to the possible effects on his party’s fortunes.

The malfeasance had originated in 1920, when oilmen dug into their pockets to deliver the Republican presidential nomination to Warren G. Harding, an Ohio senator whose character can be summed up in three near-rhyming words: amiable, malleable, amoral. Once elected, Harding fell in with the oilmen’s plan to loot Teapot Dome. The first step was to transfer jurisdiction over the reserve from the by-the-book U.S. Navy to the more politicized Interior Department, where a Harding crony, former New Mexico senator Albert B. Fall, had been appointed secretary. In return for hefty bribes, Fall used the small amount of oil leaking from the reserve as a pretext to issue drilling leases without competitive bidding.

By the time the public caught on, Harding had died in office in 1923 and Fall had resigned. But the stench of fraud lingered, and a Senate committee launched an investigation under the leadership of Montana Democrat Thomas Walsh. Though Walsh made some headway, his efforts met with orchestrated stonewalling: witnesses absconding, taking the Fifth Amendment, or suffering drastic failures of memory. With elections coming up in the fall of 1924, Calvin Coolidge, Harding’s running mate who had become president upon his death, seized control of the scandal by appointing special counsel to look into it. His choices were former Ohio senator Atlee Pomerene, a conservative Democrat, and Owen Roberts.

At age 48, Roberts had several things going for him: his good name; his Republican credentials; and the recommendation of Pennsylvania senator George Wharton Pepper C1887 L1889, who called him “the fighting Welshman.” But Pepper had scoffed at the Senate’s Teapot Dome hearings as “a ridiculous circus,” and little was expected of this parallel inquiry. Nevertheless, on February 17, 1924, the Senate confirmed the appointments, and the two men went to work.

One of Roberts’s first acts was to call on Senator Walsh and assure him that he hadn’t accepted the job to conduct a whitewash. Though skeptical at first, Walsh came to trust Roberts and gave him valuable leads. Roberts and Pomerene went out West to interview witnesses and follow document trails, “paying expenses out of their own pocket,” notes Laton McCartney, author of The Teapot DomeScandal, because “the $100,000 appropriated for their investigations had been held up in Congress.”

The funding eventually materialized, and Roberts in particular won praise for his canniness: summing up his Teapot Dome work, The New York Times called him “a Sherlock Holmes as well as a lawyer.” In June 1926, a great wrong was finally righted when a federal appeals court invalidated the Teapot Dome leases. A year later, however, the investigation ran out of money again, and Roberts was so disgusted that he wanted to quit. He calmed down, however, and saw the job through to the end. That came in October 1929, when a federal jury brought in the first-ever felony conviction against a Cabinet member: Albert Fall was sentenced to a year in prison and fined $100,000.

A few months later, Roberts was named by President Herbert Hoover to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court. He wasn’t Hoover’s first choice. That had been John J. Parker, a federal judge from North Carolina, who owed his defeat in the Senate (by two votes) to union opposition and a racist remark from his past. Roberts was a safe substitute, acceptable to conservatives as a strong proponent of laissez-faire capitalism, respected by liberals as the man who cleaned up Teapot Dome. In Solomon’s assessment, “the core of Robert’s appeal [was that] people could see in him whatever they liked.” The nominee’s path to the high court couldn’t have been smoother: unanimous approval by the Senate Judiciary Committee, followed by a full-Senate confirmation so perfunctory that there was neither debate nor a formal vote. Before moving to Washington, Roberts told friends he would be his own man on the court, careful not to align himself with either of its wings.

And sharply divided those wings were. On the right were four justices whose championship of unfettered private enterprise was uncompromising: Willis Van Devanter, Pierce Butler, George Sutherland, and James McReynolds, known as The Four Horsemen. On the left were Louis Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Benjamin Cardozo. In the center stood the chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, a consensus-builder who fretted about how the Court was perceived during what was shaping up as an era of economic calamity. In this context, Roberts came to the bench as a potential powerhouse; as Solomon puts it, “The Four Horsemen could not prevail without the vote of either Roberts or Hughes, nor could the liberals win without both.” It wasn’t long, however, before Roberts held the balance alone. Just as pundits used to sum up the pivotal position of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor before her retirement, or that of Justice Anthony Kennedy today, by talking about the O’Connor or Kennedy Court, so in the 1930s it was “the Roberts Court.”

Roberts didn’t make it easy for court watchers to discern a pattern in the stands he took. In Nebbia v.New York(1933), he sided with the liberals and Hughes in upholding a $5 fine imposed by the state on a farmer who had violated a law fixing the price of milk; the idea was to gain control over production and help dairy farmers survive. To the Four Horsemen, this was an easy case: government can’t mess with a man’s right to run his business as he sees fit. But Roberts, who had himself become a gentleman farmer in Chester County, Pennsylvania, saw it otherwise in the opinion he wrote for a 5-4 majority: “Equally fundamental with the private right is that of the public to regulate it in the common interest.” The decision augured well for the constitutionality of the New Deal statutes that the president and the Congress were improvising as responses to the Depression.

The augury proved to be misleading. Over the next three years, Roberts leaned the other way, relying on a narrow interpretation of the term “interstate commerce” (economic activities not involved in such commerce are considered beyond Congress’s reach) and often casting the deciding vote. Solomon totes up the score as it stood in 1936: “Of the ten New Deal laws that had come before the Supreme Court, the justices had overturned eight.” And although in 1933 Farmer Roberts had saved New York State’s milk regulation, in 1936 he helped sink the U.S. Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

Chief Justice Hughes was with him on this one, but the majority opinion Roberts wrote in United States v. Butlermay have been the least satisfactory work-product of his legal career. The case addressed a central feature of the Agriculture Adjustment Act: a tax on farm products, the proceeds of which went to pay farmers not to plant crops. As in the milk case, the object was to promote the common good by regulating supply at a time of upheaval. (Indeed, the act led off by declaring a state of emergency.) Early in his opinion, Roberts asserted that the court had only one duty when faced with a constitutional objection to a law: “to lay the article of the Constitution which is invoked beside the statute which is challenged and to decide whether the latter squares with the former.” Roberts, Hughes, and the Four Horsemen held the tax unconstitutional because it was levied for a purpose—“to regulate and control agricultural production”—that encroached, in their view, on powers reserved to the states.

In dissent, Justices Stone, Brandeis, and Cardozo objected to the decision on several grounds, the most telling of which was that it left the country tied up in knots: this was no time to look to the states, the dissenters pointed out, because they were “unable or unwilling to supply the necessary relief.” Law professors also took exception, but the unkindest cut may have been inflicted by the anonymous student who analyzed the case in the Penn Law Review. The principle that Congress’s powers are limited by those reserved to the states is “as vague as the due process clause,” the student wrote, “and one which in its application will extend tremendously the influence of the Supreme Court, the only body deemed capable of ascertaining the proper limitations.”

The president expressed his befuddlement, too. On March 4, 1937, after winning election to a second term, Roosevelt rattled off the various New Deal measures struck down by the Court and groused, “I defy anyone to read the opinions … and tell us exactly what, if anything, we can do for the industrial worker in this session of Congress with any reasonable certainty that what we do will not be nullified as unconstitutional.” The president failed to mention that he himself was about to take bold action: unveiling a plan to remove the Court as a roadblock to progress.

Roosevelt’s plan had a good-government pretext: that the aging court had fallen behind in its work. To fix this alleged problem (a subterfuge that fooled no one), the administration proposed legislation to let the president appoint an additional justice for each one over the age of 70, up to a total of six, thereby giving the New Deal a comfortable majority.

Legal scholars, Republican lawmakers, and even some Democrats cried foul: the proposed law would play havoc with the separation of powers. True, the Constitution is silent about the exact number of justices, which had fluctuated before settling at the standard nine in 1870. But fiddling with the number to obtain desired outcomes would subordinate the court to the president and Congress. Led by Burton Wheeler, a Montana Democrat, the Senate took particular umbrage, and in the end Roosevelt suffered an embarrassing defeat.

In the meantime, the Court had become more Roberts’s than ever. As the Court-packing bill was pending, the Court issued its decision in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937), upholding Washington State’s minimum-wage law by a 5-4 margin—majority opinion by Justice Roberts. Just the year before, however, he had been in the majority that struck down New York’s minimum-wage law, so this was definitely a switch: even Felix Frankfurter, a law professor who later became a colleague and great admirer of Roberts’s on the Court, called it a “somersault.” And it was only the beginning. Over the next few years, the Roberts Court became more tolerant of federal laws as well, upholding one New Deal measure after another, including the Social Security laws and the Wagner Act, which strengthened workers’ ability to form unions and engage in collective bargaining. Beginning with the Parrish case, the impetus for the Court-packing legislation had dwindled steadily, and wags talked about Roberts’s “switch in time.”

The wags, however, were wrong: examined closely, the timing was off. Years later, after Roberts’s death in 1955, Justice Frankfurter contributed a eulogy to a Roberts memorial issue of the Penn Law Review; in his essay, Frankfurter made public a memo Roberts had sent him after leaving the Court in 1945. As Court records showed, he had already cast his vote in the second minimum-wage case before the president announced his Court-packing scheme, but the illness of another justice had delayed the decision’s release until afterward. “These facts make it evident,” wrote Roberts, who was understandably sensitive on the point, “that no action taken by the President in the interim had any causal relation to my action in the Parrish case.”

And yet the “switch” won’t go away so easily. Though not reacting directly to Roosevelt’s plan, Roberts seems to have been chastened by scholarly criticism of his opinion in the Agricultural Adjustment Act case, and the sense of frustration voiced by his dissenting brethren, newspaper editorials, and the president.

In siding with the Court’s liberal wing in the late 1930s, then, Roberts was taking note of the national predicament, not to mention the situation in Europe, where dictatorship was a growth industry. He admitted as much in lectures he gave at Harvard Law School in 1951: “An insistence by the Court on holding federal power to what seemed its appropriate orbit when the Constitution was adopted might have resulted in even more radical changes in our dual structure [i.e., the respective spheres of federal and state government] than those which have been gradually accomplished through the extension of the limited jurisdiction conferred on the federal government.” Much as Roosevelt is said to have saved capitalism by performing radical surgery on it, Roberts can be seen as preserving the Court by finding ways to accommodate the New Deal. Solomon’s conclusion seems the right one: “The truly conservative position was to bend with the times.”

Bend, yes; break, no. Shortly before retiring from the Court, Roberts reached the limits of what he would allow the government to get away with in parlous times. The case, which arose during World War II, was Korematsu v. United States (1944), in which an American citizen of Japanese descent was charged with the crime of not being where a military order said he should be: confined with other Japanese Americans to a federal concentration camp. In one of the most repulsive Supreme Court decisions ever handed down, those stalwarts of individual liberty Hugo Black and William O. Douglas voted with the majority to uphold Korematsu’s conviction. Middle-of-the-road Justice Roberts refused to go along, however: “I dissent,” he wrote bluntly, “because I think the indisputable facts exhibit a clear violation of constitutional rights.”

Owen J. Roberts had joined the Supreme Court with no judicial experience to draw on, and he had to learn fast. Almost from the start, he found himself casting votes in cases that tested the efficacy of government at a time of unprecedented crisis. His opinions may not always be models of doctrinal rigor, but by the time he left the Court 15 years later he embodied a judicial quality as rare as it is highly prized: wisdom.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is a contributing editor of The Washington Post Book World.