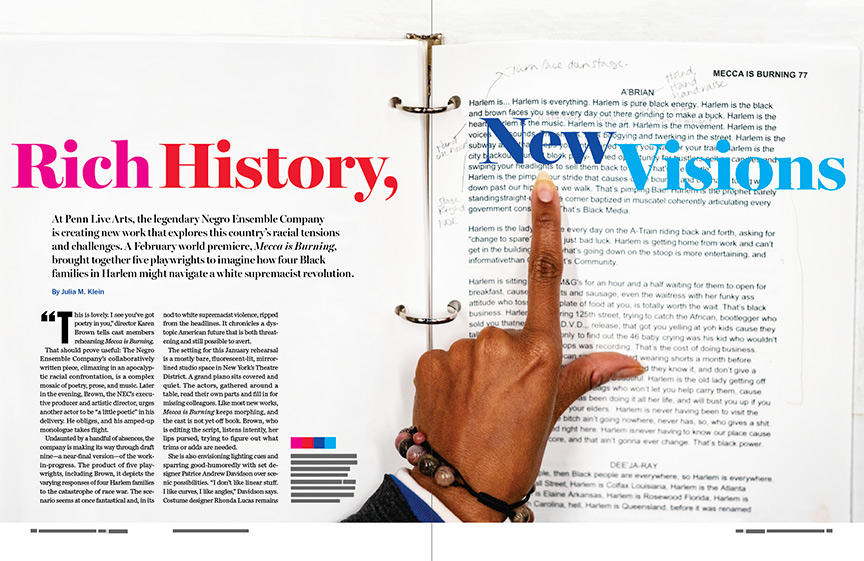

At Penn Live Arts, the legendary Negro Ensemble Company is creating new work that explores this country’s racial tensions and challenges. A February world premiere, Mecca is Burning, brought together five playwrights to imagine how four Black families in Harlem might navigate a white-supremacist revolution.

By Julia M. Klein | Photography by Don Hamerman

“This is lovely. I see you’ve got poetry in you,” director Karen Brown tells cast members rehearsing Mecca is Burning.

That should prove useful: The Negro Ensemble Company’s collaboratively written piece, climaxing in an apocalyptic racial confrontation, is a complex mosaic of poetry, prose, and music. Later in the evening, Brown, the NEC’s executive producer and artistic director, urges another actor to be “a little poetic” in his delivery. He obliges, and his amped-up monologue takes flight.

Undaunted by a handful of absences, the company is making its way through draft nine—a near-final version—of the work-in-progress. The product of five playwrights, including Brown, it depicts the varying responses of four Harlem families to the catastrophe of race war. The scenario seems at once fantastical and, in its nod to white supremacist violence, ripped from the headlines. It chronicles a dystopic American future that is both threatening and still possible to avert.

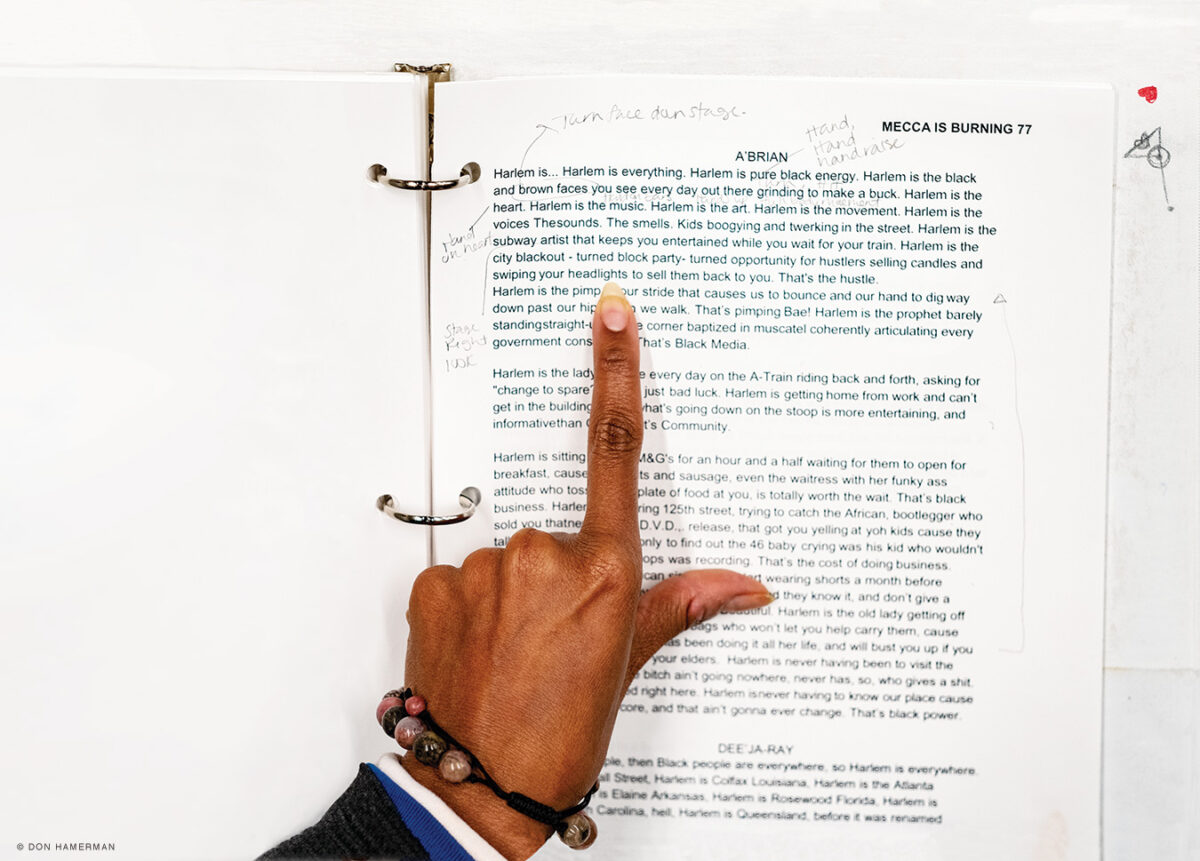

The setting for this January rehearsal is a mostly bare, fluorescent-lit, mirror-lined studio space in New York’s Theatre District. A grand piano sits covered and quiet. The actors, gathered around a table, read their own parts and fill in for missing colleagues. Like most new works, Mecca is Burning keeps morphing, and the cast is not yet off book. Brown, who is editing the script, listens intently, her lips pursed, trying to figure out what trims or adds are needed.

She is also envisioning lighting cues and sparring good-humoredly with set designer Patrice Andrew Davidson over scenic possibilities. “I don’t like linear stuff. I like curves, I like angles,” Davidson says. Costume designer Rhonda Lucas remains noncommittal about her ideas. “I want to see how the actors perform, how they move,” she says in an interview. “All I know is that it’s present time.”

“This is the final day of the development with the cast,” Brown explains during a rehearsal break. “Next we’re going to start blocking it, and giving people beats and motivations—all that actor stuff.”

Opening night is just over a month away.

The mid-February premiere of Mecca is Burning at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts represents the culmination of the renowned New York-based company’s 2022–23 residency at Penn Live Arts. As artist-in-residence of the Brownstein Residency for Artistic Innovation at Penn Live Arts, and with additional support from the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation, the group has been creating work that embodies contemporary Black concerns, as well as interacting with Penn students and community members.

Christopher A. Gruits, executive and artistic director of Penn Live Arts, says awarding the residency to the NEC made organizational sense. “There’s a really long history here of supporting Black storytelling,” he says, citing past productions of August Wilson plays and the University’s association with the BlackStar Film Festival. “I was trying to build on that legacy and really think about how we can create formats and platforms for Black artists to go deeper in addressing some of the issues that are facing Black America today.”

In October, the NEC premiered Our Voices, Our Time: One-Act Play Festival at Penn, before transferring the three one-acts to New York’s Cherry Lane Theatre. This past fall, NEC members, including Brown, paid two visits to the University’s academically based community service class, “August Wilson and Beyond,” cotaughtby Herman Beavers, the Julie Beren Platt and Marc E. Platt President’s Distinguished Professor of English and Africana Studies.

“We wanted our students to have a sense of the productivity, but also the excitement and the challenges that went with trying to start a theater company,” Beavers says. “When the NEC came on the scene, there were still people saying, ‘What is there about Black life that’s even worth depicting on Broadway?’”

Since its inception in 1967, the NEC has built a reputation for advancing Black playwrights, directors, actors, and perspectives. The company’s alumni include Denzel Washington, Samuel L. Jackson, Louis Gossett Jr., Sherman Hemsley, Phylicia Rashad, Angela Bassett, Laurence Fishburne, and Ruben Santiago-Hudson. “The NEC is this place where several generations of actors went to be trained in the craft of theater,” Beavers says.

The group’s founders—playwright Douglas Turner Ward, producer/actor Robert Hooks, and theater manager Gerald Krone—drew inspiration, in part, from the 1959 Broadway production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun and the 1964 Obie Award-winning Dutchman by LeRoi Jones (the future Amiri Baraka). “Doug [Ward] was influenced by the principle of being able to create out of your own experience and have it respected,” says Brown, a former journalist and educator.

In 1973, Joe Walker’s The River Niger, about a contemporary Black family in Harlem, became the first NEC production to transfer to Broadway, where it won a Tony Award for Best Play. It was adapted into a 1976 film starring Cicely Tyson and James Earl Jones. In 1981, the NEC premiered Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play, about an investigation into the murder of a Black sergeant on a Louisiana Army base during World War II. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and was adapted into the 1984 film A Soldier’s Story. The original production, featuring Samuel L. Jackson and Denzel Washington, never made it to Broadway, but a recent Roundabout Theatre Company revival did, winning a 2020 Tony Award. The national touring version played Philadelphia this winter under the auspices of the Kimmel Cultural Campus’s Broadway Series.

In Beavers’ view, the NEC diverged from the more overtly political Black Arts movement of the 1960s and ’70s in its emphasis on “glimpses into Black life.” Its work, he says, tended to be less formally experimental, “more grounded in the idea of the well-made play,” and “not necessarily as confrontational.”

“I don’t think NEC has ever been one of those identifiable ‘in your face’ political theaters,” says Levy Lee Simon, one of the Mecca playwrights and a former NEC actor. “But I think that anything we do is political when we are being bold enough to tell our own stories. It’s just a different approach.”

Brown describes the NEC’s mission as presenting Black perspectives to a diverse audience.“We all experience the same things: love, joy, hate, pain, passion,” she says. “We are charged as the Negro Ensemble Company to try to provide some voice for what is being felt in this community. What the University of Pennsylvania is providing for us is an opportunity and a platform to reach outside the community.”

“We are bringing back our voices, our time, so to speak, into the arts,” says Steven Peacock Jacoby, an actor who made his NEC debut in the one-act play festival. “We are an expressive people. These are diverse Black voices stating their frustrations, their love—our humanity. We’re not just caricatures. We’ve given so much to this world, it’s about time we get our just due.”

This year’s NEC premieres, both the one-acts and Mecca is Burning, tackle racism and violence head-on. “We have to define ourselves as a company of the now,” says Brown. She argues that the Black community is increasingly embattled: “We are looking at a rise in divisiveness, a rise in racism. We are looking at the limiting of women’s rights, of voting rights for African American people.”

In Cris Eli Blak’s one-act, Clipper Cut Nation, a Black barbershop in an unspecified big city is the setting for a confrontation between a father, Sanford Grady, who years earlier lost his son to street violence, and a mayoral candidate who may have been culpable. “That really hit home to a lot of people,” says Jacoby, who played the bereaved father.

Another of the one-acts, Cynthia Grace Robinson’s What If … ?, is a direct response to the murder of George Floyd, in May 2020, by a Minneapolis policeman. One character, a Howard University student, tells her mother, a nurse caring for COVID patients, about a similar confrontation involving her best friend. The worried mother urges her daughter to avoid a subsequent protest. “I’ve already lost your father,” she says. “I can’t lose you, too.”

In Mecca is Burning, the strains of gentrification—or what playwright Blak calls “an invasion, an occupation, a stealing of property”—foreshadow armed conflict between whites and Blacks. In the world of the play, the inciting factor is former President Trump’s flight from arrest, which touches off nationwide white supremacist riots. Over the course of a day, characters of varying temperaments, inclinations, and politics must decide how to respond: Should they try to escape the conflagration, or take up arms? “Sometimes the pressures of being Black in America are just too much,” one male character says.

In Mecca, Jacoby plays yet another man marked by loss: a widower, Henry, seeking to protect both his daughter and his community. “He wants to make a difference,” says Jacoby. “He doesn’t want to be part of the scenery.”

Having seen A Soldier’s Play as a child, Jacoby grew up admiring the NEC. Initially drawn to broadcasting, he was living and studying in London when, in November 1995, he saw Guy Burgess play Othello. “I can do this,” he told himself. He went on to attend New York’s Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute, where his mentor was the late Irma Sandrey, a member of the Actors Studio and a protégée of Strasberg himself.

Despite a long list of acting credits, ranging from theater to commercials, Jacoby sometimes needs to take day jobs; he currently is a doorman at a Brooklyn hotel. Mecca is Burning has been a particular acting challenge, he says: “You have different points of views and different styles of writing—and how it’s structured feels more like vignettes of different characters in one setting. We’re calling it a montage.”

Writing collaboratively required “piecing a puzzle together,” Blak says during a Zoom call along with two of his fellow playwrights, Levy Lee Simon and Lisa McCree. The first step, in October, was “a lot of conversations,” he says. “We started with the seeds—we didn’t start with the plant.”

The Mecca playwrights (including Mona R. Washington, who also authored the third one-act) wrote their scenes, each involving a specific family, separately. They then conferred over Zoom, refining what Blak calls a “huge Moby-Dick version of the show.”

While the central conflict and characters didn’t change, Blaksays, Brown’s gentle guidance helped fine-tune the script. “We would listen to [the pages] together. We would see what worked,” he says.

“We all have different voices, yet we’re all aiming for the same target. The importance of having multiple writers is to show there’s no monolithic experience to Black life. There is no one way. There are multitudes, there are layers. And that’s why the piece isn’t just one song on repeat.”

When he was growing up in Houston, Blak gravitated to basketball and hip hop. “Theater felt expensive and inaccessible and costume-y and extravagant,” he says. Then he realized: “Maybe I can change that, maybe I can tell the stories that I wish I had been exposed to when I was growing up.” He first connected with the NEC in 2020, when he won its 10-minute play contest.

As a child actor, McCree says, “I was never in anything that I could identify with. I was tired of playing Glinda, the Good Witch, but never anything that really spoke to my experience as a young Black child.” Her playwriting career got a boost in the 1990s when she won a New York University competition. Now based in Connecticut, McCree spent a quarter century in Harlem and still considers it home. So when Simon, a longtime friend, asked her to join the Mecca project, she “just jumped on board.”

Born and raised in Harlem, Simon, who now lives in Los Angeles, is an award-winning actor, director, and playwright who “always felt a calling” to theater. His first professional acting job, in 1987, was with the NEC, in a revival of Ceremonies in Dark Old Men. New York’s Circle Repertory Company produced his first play, God, the Crackhouse, and the Devil, in 1994. In 1996, he won a fellowship to the University of Iowa’s three-year Playwrights Workshop, where he earned an MFA. “I figured I’d write a play a year, and ended up writing 18,” a dozen of which have since been produced, he says. Before Mecca, his work had received 45 productions.

Last fall, Brown called Simon “out of the blue” and told him she was planning a play reflecting, as he recalls, “how our people are responding to the political climate of the world today.” Says Simon: “I was in right there. I consider myself as much an activist as a playwright and an artist.”

As Simon sees it, “you get to a point where Black folk living in this country have done everything: we’ve protested, marched and sung, and things are still the same.” He makes a small correction: “They have improved marginally. But we just had another police shooting recently. So what do we do? When I look at this country’s history, everything that’s happened, happened collectively. We can’t do it all ourselves.”

“We’ve been asking people to stand up for too long,” Blak says. “What we should be asking is, ‘Stay standing.’ How many reckonings have we had? We keep sitting down. Change is only possible with conversation and consistency. I hope this shows just how chaotic it can get, how dire it can get, if we just keep waiting for the change.”

“Silence is violence against us,” says McCree. “It’s not important that there [be] a resolution in this piece. Because there’s not a resolution in real life.”

It’s February 15, an uncommonly springlike evening. After Zoom meetings and rehearsals in New York and Philadelphia, Mecca is Burning has landed in the Annenberg Center’s Harold Prince Theatre for opening night.

Clusters of furniture onstage represent four apartments in a Harlem building. Two couples, a father and daughter, and two sisters talk mostly of domestic concerns: work, school, conflicts over where and how to live. But the politics of race keeps intruding.

A video backdrop sets the scene with a loop of Harlem images, from magnificent brownstones to gritty high-rises and graffiti-covered walls. Later the screen becomes a newscast announcing the flight of former President Trump from justice and the violence breaking out in its wake. Interspersed with video of the January 6, 2021 storming of the US Capitol are photographs of white-hooded Ku Klux Klansmen and grisly lynchings.

Murmuring voices outside the apartment building erupt into shouts and gunfire, shattering a fragile peace. Finally, an image of Tyre Nichols, who died in Memphis in January after a police beating, fills the screen. It is not always entirely clear what is past, what is present—or what is to come. That may be the point. In a climactic face-off, the most militant of the women sings a fragment of “Strange Fruit,” the 1930s anti-lynching ballad popularized by Billie Holliday.

Sprawling, insistently polemical, and intermittently powerful, the show runs nearly two-and-a-half hours, exhausting some audience members and inspiring others. A couple of dozen people stay afterward for a talkback with Brown, Blak, and the cast that lasts almost as long as the first act.

“I want to congratulate everybody. This was so real, so current, so raw, and yet so loving and sweet. I can’t think of anything that was left out,” says Jettie Newkirk, describing herself as “an 87-year-old Southern woman” who initially had no idea what the evening held in store. A lawyer and former educator, Newkirk chairs the Community Advisory Board of Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships.

Karen Fitzer, a 69-year-old ESL teacher, tells Brown and the company that she “fell in love with the play,” but didn’t know how to address the issues it highlighted. “How do you proceed?” she asks.

“We do things like this,” the director says.

Julia M. Klein writes frequently for the Gazette.