The Annenberg Center is back—with a full performance slate, a new name, and a half-century to celebrate.

When audiences stream back into the Annenberg Center for the first time since March 2020, they’ll spot a number of upgrades and changes—including a brand-new name out front.

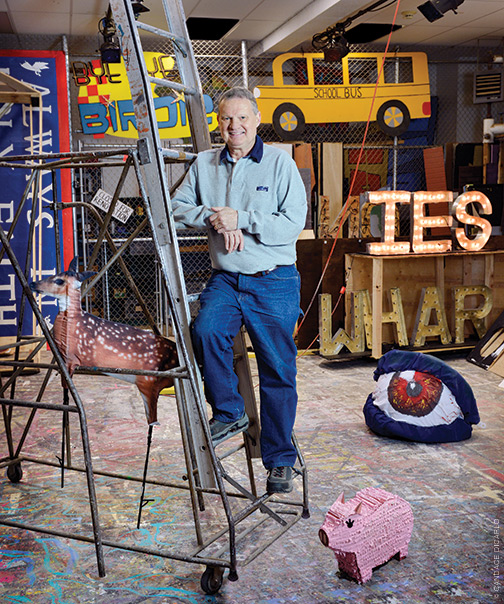

In concert with its 50th anniversary, the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts launched a new brand identity: Penn Live Arts. The building still goes by its original name, but the production side goes by the new handle. “We’re a real hybrid organization—we serve both the University and the public,” says Christopher Gruits, the executive and artistic director of Penn Live Arts. “We wanted a brand that better reflected our connection to Penn and how we serve students, but also our connection to audiences beyond the Annenberg Center’s four walls.”

For the last 20 months, its audiences have only been outside those four walls. COVID-19 forced the center to close abruptly and rework all of its planned events for the 2020–21 season. It wound up copresenting several off-campus, outdoor performances with Philly’s the Crossing choir and managing 20 live events—five of them world premieres—performed inside the center and streamed live online.

With its branding makeover unfolding at the same time, “Live” felt crucial to the new Penn Live Arts name. “In a period that was so challenging to have live performance, we realized how important and special it really was,” Gruits says. “Live” also reinforces the center’s “50-year history of presenting really groundbreaking work in live performance,” he adds.

That history began in 1965, when Penn asked the Annenberg School for Communication’s then-dean, George Gerbner, to help establish and lead a much-desired center for the performing arts on campus. After two years of planning and four of construction—with a $5.7 million price tag—the Annenberg Center held its first performance in April 1971.

“It was really the first performing arts center in Philadelphia—meaning it had multiple spaces for performance and its focus was multidisciplinary,” Gruits says. Its earliest offerings included a stage comedy starring Judd Hirsch (pre-Taxi fame) and plays directed by Harold Prince C’48 Hon’71, who was fresh off a Tony win for Company on Broadway and whose “very innovative theater here … became a big part of our early history,” Gruits says.

By the mid-1970s, Glenn Close and Shirley Knight were sharing the center’s stage in A Streetcar Named Desire, andChristopher Walken appeared in Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth. In 1984, the center introduced Philly to playwright August Wilson, staging Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom before it moved to Broadway.

Jazz, world, and contemporary music became mainstays, with Philly debuts from Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and other rising stars. The center also dove into dance, launching its Dance Celebration series and hosting Martha Graham Dance Company, Twyla Tharp, the Paul Taylor Dance Company and, over the last several decades, “really every big name in modern dance,” Gruits says.

“The Annenberg Center has a really long history of focusing on new work and experimental programs that you can’t really see otherwise in the city,” he adds. “We hear so often from our audiences that they love coming here because they know they can trust us for the best in dance, music, theater, and film.”

Today the center houses rehearsal rooms, theater arts classes, a new Arts Lounge space, and offices, in addition to its three theaters: the Harold L. Zellerbach Theatre, with roughly 900 seats; the Harold Prince black box theater, with roughly 200; and the 115-seat Bruce Montgomery Theatre.

“If you look at where the center’s located, it’s kind of a central hub on campus,” Gruits says, “and it’s also a crossroads for a lot of the arts at Penn.” Pop inside on a given day, and you may find any number of people on its stages: student theater and singing groups, panelists at academic conferences, Patti Smith rocking out, or Malcolm Gladwell unspooling his latest theories. That’s on top of the center’s professional programming slate, which this year features 26 events.

The 2021–22 season kicked off this fall with an online film series and an outdoor performance at Morris Arboretum.

But the center soon plans to welcome audiences back inside Zellerbach with performances from Grammy-winning jazz singer Cécile McLorin Salvant and mandolinist and vocalist Chris Thile in December and funk and soul jazz saxophonist Maceo Parker in February.

Though this year marks the official 50th anniversary season, Gruits is holding off on most of the festivities until next fall, in hopes that the health crisis will be more stable by then. “I suppose you could say we’re in a two-year celebration of our 50th,” he says, “but really the 22–23 season is when you’ll see some really big programs and residencies that reflect back on the anniversary of the center.”

Moving forward, he also plans to focus on “using the campus as our canvas” while continuing to think outside the center’s walls. “We’re really considering performance spaces that are unpredictable or surprising,” he adds. “And at the same time, we’re making a deeper commitment to work that will engage both Penn and Philadelphia in the big questions that these artists are asking.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06