The 2004 MacArthur Foundation Fellow and nursing professor calls on clinicians to listen to patients “talk about what hurts, where the itch is, how tired they are, what they’ve done about it, and how illness has changed the way they live.”

By Peter Nichols | Photography by Addison Geary

Behind the open door of Dr. Sarah Kagan’s tiny office, stuffed sideways among shelves crowded with titles like Nursing Care of Older Adults and Osteoporosis and Cancer Care Nursing, is a fat tome by literary critic Harold Bloom entitled Genius. Outside her door, in the waiting area of Penn’s Center for Gerontologic Nursing Science, are little baskets and vases of dried flowers. One bunch hangs upside down from the handle of a file cabinet—faded, brittle, but still holding a blush of beauty.

Bloom’s book and the bouquets are gifts that came to Kagan, the Doris R. Schwartz Associate Professor of Gerontological Nursing, last October when she was named one of 24 MacArthur fellows. At age 41, she is one of the youngest recipients. The fellowships come with a no-strings-attached stipend of $500,000. Kagan is only the second nurse to receive a MacArthur over the more than two decades that the foundation has been making its annual investment in America’s most original thinkers and doers. The first was Penn alumna Dr. Ruth Lubic NHP’55 who was recognized in 1993 for her pioneering work in a Bronx birthing center.

Kagan seems baffled that she should be singled out for the honor and enjoys colleagues’ irreverence over the fellowship’s popular sobriquet, “genius award.” During last fall’s annual conference of the Gerontological Society of America, not long after being overtaken by MacArthur celebrity, she shared a hotel room with two nursing professors who had agreed to rise with her at five o’clock each morning for exercise. When the alarm summoned the bunkmates from sleep in the pre-caffeinated darkness, a weary, pillow-muffled voice called back, “Whose genius idea was this?”

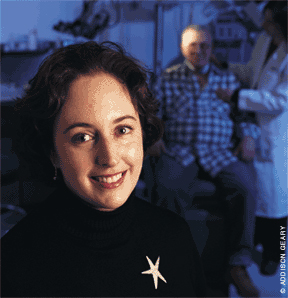

“I’ve developed a media-friendly alter ego who no longer complains when her photograph is taken,” says Kagan brightly, “and I’m also learning not to blink … People have this big-hairy-monster notion of genius, but I’m still the same kind of weirdo thinker I was before. It’s just that the MacArthur Foundation blessed it.”

The academic journals still turn down submissions in which she tries to think past current assumptions and business-as-usual clinical practice, the very thing that caught the eye of the MacArthur selection committee. The foundation’s website states, “In an era when health care systems show ever-increasing signs of strain, characterized by nursing shortages, physician overload, and consumer bewilderment, Kagan surfaces as an energetic and creative countervailing force.”

Kagan has short, wavy, brown hair and a patch of freckles across her nose and under her large eyes. She grew up on a family farm in Lower Michigan, not a Midwestern spread handed down from an earlier generation but one started up by her parents during the countercultural romanticism of the ’60s. “Successful isn’t really the issue,” she explains about the farm. “It’s, ‘Did you survive or not?’ My everyday life was arguing with my mother about whether she was going to do morning chores or I was going to do them.”

Before finishing high school, she walked, SAT scores in hand, into the office of the admissions director at Kalamazoo College, which was near home. “I wanted something more interesting than high school,” she told her and asked to be enrolled. In sophomore year she transferred to the University of Chicago. “No one ever asked for a diploma, and I never felt it to be required.” She wandered through Chicago’s curriculum in search of herself, declaring a behavioral-science major in her senior year. It wasn’t until after graduation that she decided to pursue a nursing career, in part because she liked its blend of science and service. “What I really loved was hearing people’s stories, and I particularly enjoyed working with older people—in part, I suppose, because they have more stories to tell.”

She went back to school and earned a B.S.N. from Rush University and an M.S.N. from the University of California, San Francisco. As a graduate student, she worked the night shift as a staff nurse on a cancer ward but came to Penn after completing her doctorate at UCSF in 1994. “Penn is the one place where I can integrate research, education, and practice in a way that’s uniquely mine.”

According to Dr. Neville Strumpf, director of the Center for Gerontologic Nursing Science, “Sarah is unusual in her blend of practice, scholarship, and teaching. Most academics are just that—pretty academic and not at all rooted in the real world.” Kagan still carries a beeper, makes hospital rounds most days, and is a frequent on-call resource for doctors and nurses facing tough cases.

Ann Luther, a clinical nurse specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, points out that nurses with the highest academic credentials are usually the most removed from the patient’s bedside. “Yes, Sarah has a Ph.D., but she knows what a composite resection with a microvascular free flap is and the potentially debilitating effects of this surgery on an 80 year-old patient,” she says. “In other words, the practice component of nursing is central to her [scholarly] practice, not an afterthought.”

At Penn, Kagan has two clinical appointments: as a Gerontology Clinical Nurse Specialist in Medical Nursing at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and with the Department of Otorhino-laryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. She is also part of the Abramson Cancer Center. An advanced practice nurse, she consults with patients, families, and medical teams on the complex needs of mostly older adults and on wound-management and other symptoms associated with cancer, particularly head and neck cancers. Dr. Lynn Schuchter, a physician in the medical school’s hematology/oncology division, often calls on Kagan for help with patients suffering complications from ulcerated cancers and similar problems. She describes Kagan’s particular gift as “wound care, but so much more.”

The nurse-scholar is currently at work on her second book, a study of cancer in the elderly aimed at medical professionals as well as a general audience, and is co-teaching three courses this semester: one on nursing care of the older adult, another on dementia, and a third comparing health care in the U.S., Hong Kong, and China. To balance the stress, she likes to pull from a stack of “trashy novels” on her bed stand or curl up with her three cats or bake cookies and brownies for her students. “Chocolate makes everything better” is the manifesto she hurls in the face of a full and busy life.

The rejiggering of how doctors, hospitals, governments, and insurance companies do business together—as though they comprised a widget industry—puts the emphasis on procedures and systems instead of people, Kagan argues. “American health-care is very much about fitting into the boxes. I worry about the fact that we create structures where we’re checking boxes rather than figuring out what individual patients need.”

In her clinical practice, Kagan is very much about listening to how patients and families talk about themselves, their lives, and their ills. “I think the typical thing—and this is what we teach clinicians—is to have a basic framework of, If this, then that. We try to use logical paths for decision-making. I think that it’s harder to teach the relationship piece, though we emphasize it quite a bit in medical and nursing education.”

Because they are experts, Kagan points out, health professionals often feel pressure to provide answers, to tell patients what they need to do rather than listen to them talk about what hurts, where the itch is, how tired they are, what they’ve done about it, and how illness has changed the way they live. It is precisely in these narratives, she has discovered, that much of the needed diagnostic and treatment information can be found. She acknowledges the time burdens that doctors and nurses labor under—the need for efficiency imposed by managed care. But putting in the time upfront, she insists, to hear “symptom stories” or to probe for what patients are experiencing—and what they hope for—is not more time-consuming but less.

“As nurses, it’s our responsibility to step back and say, ‘Let’s find out where this person is now and what responses to illness are evident, and not make judgments about how much assistance this person needs.’ My job is to fix what I can—not to cure diseases but to fix symptoms and side effects—and then help people sort out for themselves how they’re going to live with whatever remains. My job is to ask, ‘What’s bothersome, and what do you want to do about it?’”

Much of Kagan’s research and clinical practice relates to care of the elderly, particularly old people with cancer. Since cancer is the third leading cause of death in adults over 65, notes Strumpf, the nurse-scholar’s approach to health-care will become increasingly important as society grows older.

Currently, more than 12 percent of the U.S. population is age 65 or over, which comes to about 35 million people. Over the next three decades, the number of older Americans is expected to double. They will make up nearly 20 percent of the census count by 2030.

In 1900, the average life expectancy was just over 47. By 2050, it is projected that the average American will live a little more than 80 years. “There is, I think, a very fervent American hope or belief that health will come without a price and that cure comes at no cost,” Kagan muses. “Ours is not an infinite lifespan. I don’t think we’ll be able to cure the fundamental problem of senescence—the fact that the minute our organism is fully formed there are aging processes that immediately kick in—and with senescence comes increased risk of disease.”

As the population grows older, society will assume an ever greater burden of disease and disability—the cost of longevity—including a higher incidence of cancer. Cancer rates increase sharply with age. More than half of all malignancies and more than 70 percent of cancer deaths occur in the elderly. “What we know about cancer is that you’re much more likely to be old and have cancer than to be young. So the common experience—and one that most American adults these days have at least cursory familiarity with—is that you’re old, you’re frail, you have cancer, you have other chronic diseases.”

There are now more than 4 million people age 85 and over. This most frail age group is the fastest growing segment of the population and is expected to hit 19 million half-way through the 21st century.

“It’s a really scary curve,” says Kagan. “Those people will have differential disease patterns for which our systems of care are not well equipped, and we’re still allocating way too few dollars and way too little public policy and thought to figuring out how we’re going to create a seamless system of care that doesn’t make people who will be providing for their older relatives wish that they could die.”

Her pioneering book, Older Adults Coping with Cancer: Integrating Cancer into a Life Mostly Lived, is one of the first in-depth studies of the patient population in which cancer most frequently occurs. Surprisingly, cancer research has focused mostly on younger age groups and results tend to be extrapolated to older people. But cancer unfolds differently in elders—from how aged malignant cells respond to treatment to how cancer symptoms present themselves in patients who suffer from several chronic illnesses. Seniors also construe what it means to have the disease differently than do younger people. Kagan’s book looks at several cases of how older adults understand and come to live with cancer.

When she started out on the interviews that underpin Older Adults Coping with Cancer, Kagan still clung to the “health-care provider bias”—an approach that sticks to scripted pathways leading from symptoms to treatments: If you have nausea from chemotherapy, take this pill. About six months into the research, her Aunt Barbara was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma, an aggressive and lethal cancer. Kagan, who was close to her aunt, put the research aside and became Barbara’s caregiver. Suddenly, all the boxes and checklists didn’t fit with the struggle she shared with her beloved aunt. The this-can’t-be-happening sense of unreality on top of So this is what a radiation-oncology department looks like, and Why’s Barbara pacing and chattering on about the damn funeral when I’m trying to understand the plan for her radiation? could not be channeled down the logical pathways her training had laid out. Nothing made sense; everything was uncertain, but Kagan listened closely to what Aunt Barbara needed, hearing the “little things” that would have been missed by her professional-nurse “bias.” “I experienced cancer in ways other than cognitive,” she wrote afterward. “I knew cancer through physical burdens, sensory overload, and emotional highs and lows that colored my lens anew.”

That wrenching, “noncognitive” experience broke open a more feeling part of Kagan that took up residence in her psyche right beside her more analytical self. Together, she believes, they make her a better nurse—and a more effective teacher and researcher.

“It’s inexplicable to us as clinicians,” she says, “unless we remember that we all have that history and those hopes and those dreams attached to significant relationships in our lives. As clinicians, we divorce ourselves from them because our loved ones aren’t at work with us. But we’re treating families, and that has much to do with cancer and with being old.”

After Barbara’s death, Kagan returned to her research with a deeper appreciation for the stories elders tell about what it feels like to be old and have cancer. Everyone has a story, Kagan observes, and the narratives we make up about ourselves change as time goes by. When age or illness challenge who we think we are, we tell stories that reflect it. “To approach any interaction, but particularly as a clinician in healthcare, as though the story doesn’t matter, gives us no space,” she says. “In order to do something for someone, which is fundamentally what health-care is about, you have to know the story, because without it you won’t know what to do or whether what you have done has helped.”

One of her most surprising discoveries is that, unlike younger people, older adults don’t view cancer as “the worst thing” that could happen to them. Lance Armstrong, the champion cyclist, put his life on hold and all his energy into beating back his malignancy. Being “cancer free” became his reason for living, and his “cure” is framed by the pharmaceutical industry and the cancer establishment as a story of triumph and living against the odds.

That all-out “war on cancer” is typical of those who still have much of their lives before them, Kagan explains, but seniors who are at the waning end of a mostly lived life have neither the energy nor the time. For many of the elderly, cancer is just one of two or three or five illnesses they worry about. Breaking a hip is likely the worst thing because you could no longer take care of a beloved spouse, for instance, or get to the bathroom. With cancer, you may remain independent even while undergoing chemo and continue doing, in some measure, the things that make life worthwhile.

“The older people I interviewed—the people who gave me their voices—didn’t say, ‘Well, this is my cancer and this is me,’” she explains. “Nurses and physicians, because the cancer is their business, would very much like to separate them. That separation makes it easier for us to be clinicians, but it doesn’t really fit with how my work has reflected older people managing their diseases. Their cancer fits into their lives in a variety of ways.”

Older Adults Coping with Cancer traces out characteristic stages in how the elderly deal with pain, nausea, fatigue, and other illness or treatment symptoms and weave them into “a life mostly lived.” The basic story pattern is summarized in four phases: life before cancer, coming to “bouts” with yourself, redefining the thresholds of daily living, and living on new terms. The process moves from a stark inner dialogue about a cancer diagnosis: What does this mean for me and the ones I love? What does it mean for my expectations about the remainder of my life? What am I willing and not willing to give up? The dialogue quiets down when answers and management strategies are found, but it starts up again when the new terms and thresholds for daily living are breached once more by suffering. Then a new calculus and a new contract between pain and the self must be negotiated.

For the elderly, “[c]ancer is integrated into an existing life and into patterns of daily living,” Kagan writes. “That life has a long history and a recognized end in mortality. Cancer does not take over the life or sit in opposition to it. Rather, in this process, cancer is one of several losses in health, function, or both, that must be included in daily living.” When integrating cancer (and the myriad afflictions of old age) no longer yields an acceptable “quality of daily living,” a level of function and comfort that each individual defines in their inner dialogue, then death begins to look like a better option.

The theory that Kagan builds up from elders’ stories should replace popular assumptions about waging an all-consuming war against cancer or an identity of older people as primarily “old” rather than as individuals shaped by their life experiences. Clinicians who base their approach on popular constructions of what it means to be old and have cancer will offer less-than-satisfying care to patients they fundamentally just don’t “get.” Many of the students and staff nurses Kagan works with, though, have picked up on her research and by-example leadership.

Anna Beeber GNu’00 who is working through the Ph.D. program, has been mentored by Kagan as a HUP staff nurse and through her M.S.N. studies. When most of the other students wanted to enter hot specialties like obstetrics and critical care, Kagan helped the young nurse come out of the closet regarding her interest in geriatrics. “I never knew what it meant to be a nurse until I met her,” says Beeber, who recalls working with Kagan and an old man with a stubborn bedsore. “While the apparent problem for this patient was wound-management, I began to realize that the nursing required was so much more than wound-care. We were evaluating the patient’s response to his illness, discussing his general views about life and feelings about death, and, most importantly, focusing on relieving his suffering. We were not there to treat the problem, but instead to learn about the patient and learn from the patient. With this information, we could then create a personalized plan of care.”

Kagan’s compassionate skill and expertise in gero-oncology have been sought at the bedsides of patients, in consultation rooms with medical teams, in classrooms of nursing students, and in big lecture halls as keynote speaker in Hong Kong, Sweden, England, and elsewhere. Her students and HUP’s ward nurses all speak of her brilliance and unflagging generosity. In 1996, Kagan was the winner of HUP’s Nursing Excellence Award, and she was recognized for distinguished teaching with a Lindback Award in 1996. Margaret Crighton Nu’94 GNu’01, another of Kagan’s Ph.D. students and a former HUP nurse, reports that Kagan has helped change “for the better” how many of the nurses practice there. “They will take that with them wherever they go,” Crighton says. “Everyone admires her.”

Harold Bloom’s notion of genius is not a hairy monster. A literary critic who holds up Shakespeare as the “supreme genius,” he offers his own personal definition. “Because of Shakespeare,” he writes, “we see what otherwise we could not see.” One litmus-test that readers should pose to ascertain whether they have encountered literary genius is, he says,“Has my awareness been intensified, my consciousness widened and clarified?”

It’s ironic that Kagan should, in some sense, be recognized for what the medical and nursing establishments already know deep down: that the individual person is the center of care, that older adults suffer most from cancer and that, therefore, we ought to be listening to them. It’s the human relationships that matter most. And yet it’s these basic and obvious truths that seem hardest to put into practice in our fraying health-care system.

“Sarah has the mark of a true mentor,” says Crighton. “She sees in her students what they can’t see themselves, [and] she has an uncanny way of getting people to see things in a totally new light.” The MacArthur Foundation, it seems, is intent on disseminating a little of that light.

Kagan studies and cares for some of society’s most fragile members, a population that rarely makes headlines as the subject of scientific breakthroughs. “Nor are these patients the customary first choice of nurses and physicians delivering patient care,” notes Strumpf. Old people with cancer are not cute and charming and “tragic” like little kids with cancer, says Kagan, but she finds something deeply satisfying in working with frail elders who over and over again display the fortitude to transcend ineluctable pain and go on living.

Grave illnesses “challenge people to dig within themselves and reflect on the lives they’ve led and try to use what they’ve learned,” says Kagan. How they respond “varies from individual to individual, but I think that as a result, I get to hear a lot of great stories—I get to know a lot of people in times that are very, very trying for them but which create opportunity and a sense of triumph. People tend to display the best in themselves when they feel as though they’ve accomplished something they believed was impossible.” That achievement can be anything from going back to work to caring for a grandchild through profound chemo fatigue or simply sitting up in bed after an arduous recovery from major surgery. Sometimes it means facing death, when it can no longer be pushed back by modern medicine. It’s not big science and high technology—it’s listening to patients, one story at a time, that can transform health care.

Kagan looks into the face of pain, decline, and death—and all the wounds of the human condition—and she doesn’t blink. She even finds joy there. “We may be weird, but we’re worth it,” she once told Beeber, encouraging the young nurse’s love of caring for the faded blooms.

“What I’ve learned is that each person’s sense of suffering is unjudgable,” Kagan says, “and being able to help people past that moment of suffering can be incredibly rewarding—the joy that you share with someone who says, ‘My pain is half of what it was last night, and I feel sooooo much better. Thank you.’”

Peter Nichols CGS’93 is the editor of Penn Arts & Sciences.