An ode to book inscriptions.

By Lauren Otis

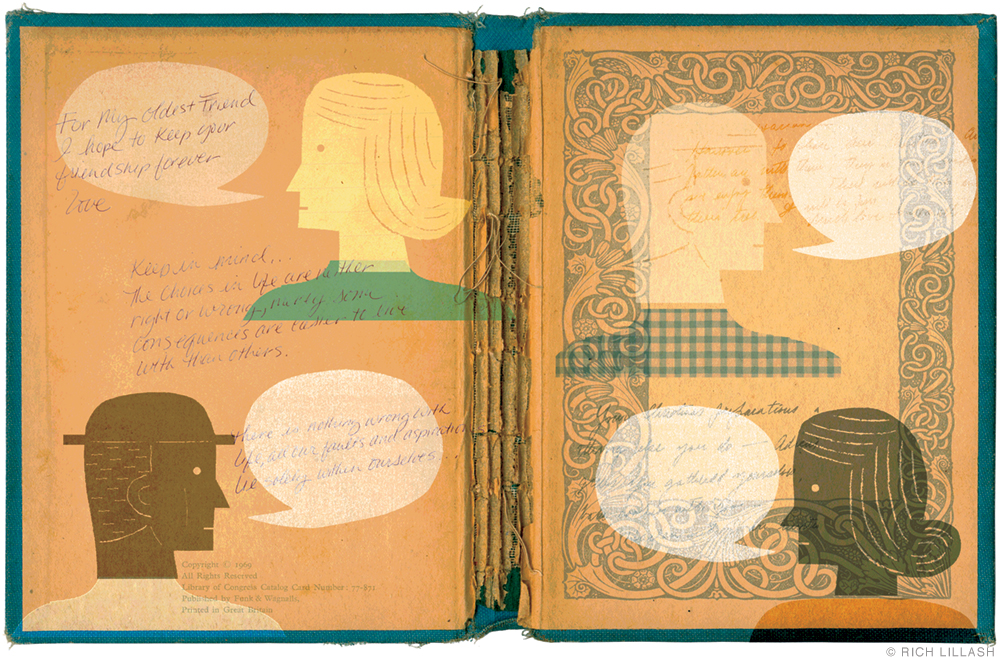

On a recent trip to San Juan, Puerto Rico, my wife and I stopped by the Libros Libres wall on Calle Loiza, one of the pleasures of the Ocean Park neighborhood where we usually stay. Here books of every shape, subject, and condition—in Spanish and English—are on display, free for the taking. I picked up a copy of The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran, one of the most widely published books on the planet, which for some reason I’d never read. The volume bore an inscription on the front endpaper which began, “For my oldest Friend / I hope to keep your / friendship forever…”

The presence of an inscription wasn’t surprising. Given its supposed status as one of the most gifted books on earth, The Prophet is likely also one of the most inscribed. Yet the inked note drew me in, as book inscriptions always do, piquing my curiosity not only about the book itself but about the people whose lives had intersected with this particular copy.

Whereas an uninscribed book is a blank slate—its previous readers, if any, an abstract group—an inscribed book tells us about the journey it has taken to us, not with an “audience” or “readership,” but via an individual person—perhaps several, but usually just one. An inscription is an invitation to conduct a sort of conversation with that person. It imbues the experience of reading with an extra layer of conjecture and rumination—about what you think about this book, what you imagine they thought, when and why the book grew special in their hands, and how it came to fly from their grasp and into yours.

I have books inscribed by my father, who would usually simply sign his name followed by the year he acquired them, a common practice of his and previous generations. Yet even that spare notation transforms these books into something more than esoteric tracts on urban planning or American history—favorite subjects for my father. It goes beyond his simple ownership of them, opening a window into the time when he bought each book, and my relation to it. How old was I? Where was I? What was happening in the world, and in the life of our family?

I still have paperback copies of V. S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River, Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, and E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, all signed by me, simply: “Lauren H. Otis, 1980,” in obvious imitation of my dad. They were assigned reading for a course on the postcolonial British novel I took that year with David Espey (who I’m happy to see still teaches in the English department at Penn). I had spent the previous year abroad at the University of Edinburgh, where my eyes had been opened for the first time to the sprawling, polyglot diaspora of cultures converging in the United Kingdom, often uneasily, because of its colonial past. Espey’s course still remains memorable for me all these years later, furthering as it did my insights into the complicated histories of Britain along with the African and Asian states it had colonized through the personalized narratives of these famous novels, as well as firing my curiosity about these faraway places and my desire to visit them.

In the intervening years I have been lucky to travel to some of these places, and along the way have also reread these books. I now feel better able to situate them in the context of the time they were written and the cultures in which they were set, and to make space alongside them for newer generations of writers native to these places who continue to grapple with the evolving and unfinished business of colonialism’s legacy. When I look at those inscriptions I wrote so many years ago, I can discern a trajectory of my life, a life of reading, writing, travel, and more, running through 1980 to the present, rather than just a set of old paperback novels.

The best-known, and perhaps most treasured, kind of book inscription is one written by the author themselves. What I have in mind are not the rote scribbles of book-signing events, but personalized offerings that may arise from friendship, love, duty, ego, or a desire to extend the reach of their creation. Yet as cool as these can be, I can’t help feeling that author-inscribed books are more about the author’s relationship to their book than the reader’s. Which is why I am partial to inscriptions penned by non-authors—from one reader to another, or one reader to themselves. These are written by people who had no stake in a book but thought enough of it to want to pass it on to others, or create a permanent place for it in their library.

I suspect that the habit of signing books we acquire, or inscribing those we gift, is fading, going the way of the printed word. Certainly a signed or inscribed book does very much come to us from the past. It can remind us of a moment in time, and of all the changes in the world, and in ourselves, since—windows into intimate worlds that are now lost or have disappeared.

I still keep volumes of children’s books inscribed for Christmas and birthdays to my children by my parents. My children now long grown, my parents long gone, these are bittersweet reminders of past shared lives and intimacy, and of the ever evolving nature of our relationships, of their importance, their impermanence, and their continuity. When my own children have children, I hope to pass these inscribed books on to them.

On the flight back from Puerto Rico, I read The Prophet. After I’d finished, I turned back to the inscription. In faded blue pen and a flowing cursive, it read:

12/90

For my oldest Friend

I hope to keep your

friendship forever

Love

It ended with an unintelligible signature beginning with maybe an L. Then on the next page, dated “25 Dec 90,” the blue cursive continued:

Keep in mind…

The choices in life are neither

right or wrong, merely some

consequences are easier to live

with than others.

Another signature, looking a little like Lyle. But it didn’t end here either, continuing on the same page:

And…

There is nothing wrong with

Life, all our faults and aspirations

Lie solely within ourselves…

And here had been placed a final signature.

Whew! OK, what was the story of the gifting, and multi-inscribing of this book over 30 years ago, to whom and why? A simple Christmas gift? Perhaps. Or did I sense something beneath these seemingly earnest written offerings of life advice? Did the recipient receive them thankfully—or more tentatively? Did that oldest friendship last? Did its memory last? After all, this book wound up in a free book exchange.

I turned to the section of The Prophet on friendship, as perhaps the long-ago recipient of this book had done. “When you part from your friend, you / grieve not; / For that which you love most in him may / be clearer in his absence, as the mountain / to the climber is clearer from the plain,” wrote Kahlil Gibran there.

I realized that the details were less important than the fact that these people had lived in close proximity and meant enough to each other that one of them had memorialized their intertwined lives in these handwritten words, on these pages open before me. The memory of their friendship had indeed lasted, thanks to this inscription. It now lived on with me.

Lauren Otis C’81 is a writer and artist based in Trenton, New Jersey. He is a former executive director of Artworks, Trenton’s nonprofit visual art center.