University Museum Director Jeremy Sabloff found his life’s path through an undergraduate anthropology course at Penn. Now, after an extraordinarily productive decade at the museum’s helm, he is ready to head back to the classroom.

By John Prendergast | Photography by Candace diCarlo

It had to have been fate.

As a Penn undergraduate in the early 1960s casting about for a major, Jeremy Sabloff C’64 was instructed to try a course in anthropology by his advisor, who told him it was, far and away, “the best department in the College.” It turned out that the course, Introduction to Archaeology, was co-taught by two giants in the field—anthropologist-essayist-poet Loren Eiseley (“a magnificent lecturer”) and Froelich Rainey, the museum’s longtime director. “I ended up majoring in anthropology and spending much of my time down at the museum,” Sabloff recalls. “Basically, I’ve always felt that Penn kind of set me on my life’s way—so I had incredibly positive feelings about it.”

After receiving his doctorate at Harvard, Sabloff went on to academic positions there and at the University of Utah, the University of New Mexico, and the University of Pittsburgh. His field work has focused on the Maya civilization, and his other research interests include archaeological theory and method and the history of American archaeology, as well as the nature of ancient civilizations. A member of the National Academy of Sciences, Sabloff has written Excavations at Seibal: Ceramics, The Cities of Ancient Mexico, and The New Archaeology and the Ancient Maya; he has also co-authored A History of American Archaeology; A Reconnaissance of Cancuen, Peten, Guatemala; Ancient Civilizations: The Near East and Mesoamerica; Cozumel: Late Maya Settlement Patterns, and The Ancient Maya City of Sayil.

In 1994, Sabloff was named director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (a position endowed by Charles K. Williams II Gr’78 Hon’97), succeeding Robert H. Dyson Jr. as museum head. He had already served as department chair at the Universities of New Mexico and Pittsburgh, but still had his doubts about moving into an administrative post—which his attachment to the University and its museum helped assuage, he says.

Sabloff’s return came close on the heels of that of another alum with a soft spot for the museum. Dr. Judith Rodin CW’66 had been elected Penn’s president, but not yet inaugurated, when Sabloff was interviewing for the directorship. He remembers being impressed that Rodin wanted to interview him herself, an indication of her high regard for the museum.

“I found it particularly attractive coming back to Penn—a sense of coming full circle—and particularly to this museum, which I think is one of the great museums in the world of its kind and which I had particularly warm feelings for,” he says. “And I think what was exciting for me was to come back and find a university that was much stronger and which has grown stronger before my eyes in the past decade.”

Certainly, the University Museum has been a full participant in that growing strength. Under Sabloff’s direction, the museum’s annual expenditures have nearly doubled, from about $8.3 million in 1995 to $16 million in 2003; non-curatorial staff increased from 95 to 120; and its endowment rose from $36.7 million in 1996 to $52.2 million last year. Scholarship, field research, and public programming have increased as well. In particular, the past decade has seen a major improvement in the preservation of the museum’s perishable collections and in its overall facilities, through the construction of the Mainwaring Wing for Collections Storage and Study and associated improvements, completed in 2002. Sabloff has also overseen the initial fundraising and first phase of construction on a project to renovate and modernize the rest of the museum’s buildings, constructed from 1899 through the 1970s.

After serving two five year terms as director of the museum, Sabloff declined the offer to sign on for a third stint when his current term expires in June. Late last year, he talked about his decision to step down, changes in the field of archaeology and anthropology and how they have affected research and programming, and the museum’s role on campus and in the world—and why it matters more than ever.

What are your feelings about leaving the directorship?

I decided if I was going to get back to teaching and research—which I wanted to do—now was the time. Secondly, and I think probably more importantly, when I came, the president and our board of overseers asked me to do certain things. I think I’ve done those, and that marked a kind of circle of completion. Also, I think 10 years is a good time. It’s good for the museum, for the institution, to have regular change.

It’s a harder job than it was when I started. It’s tiring, and this is a job that needs full-time energy—not only workdays, but evenings and weekends, and so on. I wouldn’t want to be in a situation where I wasn’t giving it full energy, and often one is the last person to realize that. I think I’ll be leaving at a time when the museum is stronger, and it’s nice to go out when you’re feeling good and not when someone comes to you and says, “It’s time.”

I very much like writing, which I have not had the time to do, and I like being with students, and I haven’t had much of a chance to do that, either. I have a sabbatical coming up next year, so it’ll give me a chance to play catch-up and retool. I have a tenured appointment in the anthropology department, and I also have a curatorship at the museum, so I’ll still have my tie to the museum, as well as my department.

You’ve spent a lot of your tenure focusing on facilities issues. Did you come in knowing that that was the biggest thing that needed to be addressed?

The most pressing issue that was put on my plate when I arrived was the state of the collections—and particularly the perishable collections, which were in storage areas in the basement and sub-basement that were never intended to be storage areas. A lot of these materials were at risk. They had been stabilized—it wasn’t that they were under active threat—but it was a situation where, for example, you had baskets that would be in barrels, in plastic, in more plastic [to protect them]. For a research collection, where we have our students, our curators, and staff, and then visitors who want to have access, it was always very difficult to get at the materials.

I think the assumption was that I would come up with a plan to climate-control the basement areas, but after looking at it and doing some comparative work, we realized that it would be incredibly expensive, and we would end up with lousy space that was air-conditioned. So I came up with a plan to take the last piece of the original Wilson Eyre architectural plan for the museum that was still available to us and complete the lower courtyard with a new storage building instead. I presented that idea to the board and the University, and it was met with great enthusiasm. The only daunting thing was the cost. As important as it was, to support something like that—that would not be a public building—you really had to know and love the museum and its mission. But the board really stepped up to support us, as did the University.

We decided to use the opportunity to do some other things, one of which was to install state-of-the-art fire-safety and security systems in the whole complex. The fire-safety needed significant updating, and the security system was almost nil. (We hadn’t had too much trouble with security, but felt that was good luck rather than our preparation.) We also wanted to create, or recreate, a grand entrance to the building and create an urban greenspace that would work for the museum and the University at large—which was accomplished with the construction of the Stoner Courtyard and Trescher Entrance. In addition, the Merle-Smith Gallery, which provided a new space for changing exhibitions of photography and artwork, was included in the project as well. And we also set up an endowment for the maintenance of the new wing, so that we would have that under control as well.

When we did all that, the pricetag came in at about $17 million—for a very specialized project. But we got incredible support. In fact, we decided in the end that our support was so broad and strong that we put every donor’s name on the plaque. Whether you gave 10 dollars or several million dollars your name is there.

In addition, the construction work allowed us to significantly increase the space of the Sumerian Dictionary Project [“Spreading the Words,” January/February 2003] in the Babylonian Section; and we were able to add a classroom for the anthropology department, among other things. The Mainwaring Wing was the feature, but there were a lot of shorts attached to it.

You mentioned how fragile the perishable collections are and the concerns about damaging them. After the Mainwaring Wing opened, how did you go about moving the objects to their new home?

We had to do a huge amount of planning. I remember someone saying, “Well, you have 125 staff members. Line them up and pass the objects.” But a number of the objects needed conservation, and we wanted to use the opportunity to check over all our cataloguing information, use new technology to digitize images of the materials that were being moved, and make sure the objects were touched as little as possible. We actually ended up having bakery carts lined with an acid-free paper so you could move an object once onto a cart or onto trays on the cart.

The architects basically created a building within the building for the storage areas, which are kept at a constant temperature and humidity. We have open fronts on the cases, so you can actually see the objects. We had further support from the William Penn Foundation to move the objects, and it took three years in the planning and execution. Just at the end of the summer of 2003, we finished moving 67,000 objects to the Mainwaring Wing. That was a major accomplishment.

Construction is continuing at the museum. In front of the west end of the building, where the main entrance used to be, it’s basically a big hole. Can you talk about that project?

Our next major construction project, the first phase of which we launched this past spring, will upgrade electricity and heating, bring air-conditioning to working areas and ultimately the major public areas. In doing that, we found that we can also make changes to create more public-gallery space by rationalizing where certain activities are located.

The first stage of the project, which is just laying the foundation of where we can put the HVAC, bring in chilled water, bring in the new electrical conduits and so on, takes about 12,000 square feet—which still leaves us with additional 13,000 square feet of new airconditioned space that we can use for new labs, and for other kinds of activities as well. That first phase is nearing completion, but we obviously have to do additional fundraising to fit out that space and move on to newer phases.

The next steps over the coming years will be to aircondition the Rotunda and Harrison Auditorium, the Coxe Wing [added in 1924], and the older part of the 1899 wing, and use this opportunity to upgrade where conservation, MASCA [Museum Applied Science Center of Archaeology], and those important activities are located. Overseeing major construction may not have been in the job description for museum director, but I’ve certainly learned, and I think this work—although parts of it have to be disruptive—has also galvanized the board and the staff.

The very first issue of the Gazette includes a report about a University Museum expedition in Nippur in what is now Iraq. Can you talk about the role the Museum has played historically at Penn and, more generally, in the fields of archaeology and anthropology?

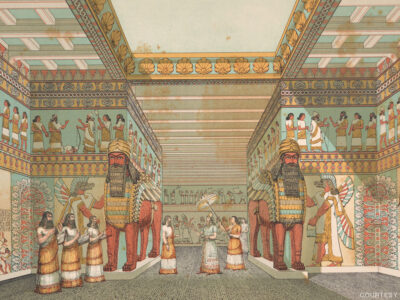

I think it’s quite fascinating. There are historical reasons that Penn, instead of establishing a major art museum, had as its major museum an institution specializing in archaeology and anthropology, one going back now more than 115 years. One of the immediate reasons was a marvelous combination of an interest in a certain kind of scholarship—and development. There was a certain group of wealthy gentlemen that Dr. William Pepper, who was then the provost, wanted to get to support the University—John Wanamaker and others. Obviously I’m simplifying it, but he wanted to attract their interest to Penn, and he knew also that a major field opening up in archaeology was what was then called the Holy Lands, or the Bible Lands, and he was interested in having the University be a pioneer in that area. So he approached Wanamaker and others and said, “The University would like to begin scholarship in this area. Would you gentlemen support this—in particular support the mounting of expeditions in the field?” Again simplifying, the answer was, “Yes, we will—if the University will pledge to build a building to house the wonderful treasures that our expeditions are going to bring back.”

That was the pact that Pepper sealed, in support of the University doing this new research—in Mesopotamia, to start with, and it spread from there. Initially, the museum was in College Hall and quickly outgrew that in the 1890s, and then was in the Furness Building. As it was [becoming] clear it was going to outgrow that, in 1895, Pepper said, “Yes, we’ll start doing the planning for a museum.” So they got the original plan from Wilson Eyre and his architectural colleagues; they went to the city to get this land donated; and they began the fundraising that resulted in the initial phase of that larger project in 1899.

And the museum was fortunate. It had through the years inspired leadership and wonderful, innovative scholars—and it also was doing good scientific work at a time when it was possible, with good relations with governments, to bring out major pieces. Also, because of the special nature of Philadelphia, these collections were augmented through loans and then gifts from the American Philosophical Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences, which decided not to go into this area. As just one example, we have a limited number of pieces that Lewis and Clark collected, that Lewis sent back to Jefferson en-route. Jefferson gave them to the American Philosophical Society, and then they came to us.

In anthropology, this University was an important early player, and more broadly the museum has served as a focus for interests in the ancient world. Of any major research university in the country, Penn has one of the largest, if not the largest, group of scholars interested in the ancient world in a variety of disciplines. If you’re looking at anthropology, if you’re looking at ancient Middle Eastern studies, Asian studies, at art history and classical studies, religious studies, the history department itself, we’re a remarkable group.

The Museum also has had incredible, almost charismatic, leaders: For example, the first full director, George Byron Gordon—a major figure in the earlier part of the 20th century—and certainly Froelich Rainey, who cemented the international reputation of this museum when he was director in the late 1940s right on through the early 1970s, which was a time of great growth. Martin Biddle for a short time, and then particularly Bob Dyson, were individuals who professionalized the museum and made it a modern leader in terms of not only research but museology—care of collections, public presentations, and so on.

Since I’ve been here, as the museum’s staff, budget, and activities grew over the past decade, it became clear that our overall administrative organization had to be rethought and strengthened, too. This restructuring has been an ongoing process with the most recent changes occurring as a result of an intensive strategic planning process several years ago. In particular, the creation of the positions of deputy director (in charge of the day-to-day operation of the museum) and deputy director for curatorial affairs (responsible for oversight of collections activities and liaison to the curators and researchers) have helped rationalize and improve the operation of the museum and have freed some of my time for additional fundraising and planning activities. These positions are ably filled by Dr. Gerry Margolis (deputy director) and Professor Harold Dibble (DDCA), who have been of tremendous support to me and the museum as a whole.

I should also mention what a great support my wife, Dr. Paula Sabloff [a senior research scientist at the Museum and an adjunct professor of anthropology], has been. Her indefatigable efforts in fundraising, her helpful ideas, and her constant encouragement have been incredibly important to me and to the museum.

The museum continues to conduct expeditions all over the world, but to a non-specialist, it can seem like those earlier years represent what one might call the “heroic” or “romantic” age of archaeology and anthropology.

Part of the romance is that you had all kinds of out-of-the-way places that were difficult to get to. Given the nature of the modern world, you can go almost anywhere. My wife works in Mongolia. There aren’t too many places that are perceived as more off-the-beaten-track—but there are Internet cafes on every corner in Ulan Bator! So it’s hard to say, “I’m going into the jungle for six months, and no one will see hide nor hair of me.” You can still go into the jungle for six months, but you might be calling by satellite phone and have some kind of computer connection.

Probably just as importantly, the goals have changed. In the case of archaeology [during] what you’re calling the great romantic period—especially archaeology as practiced by museums, but I think overall—the goal was object-oriented. It was to find great things, some of which, hopefully, you could legally bring back to the museum to be studied, displayed, and so on.

Though it’s hard to pin down which came first, archaeology today is much more interested in ideas. At the same time, given the nature of antiquities laws in virtually every country in the world, it’s impossible to bring back objects. Archaeology is more interested in how field research as well as laboratory research can illuminate our ideas of peoples and cultures in the past, and particularly how they changed and adapted to different circumstances. The end result may not be the Indiana Jones or Lara Croft kind of image—not that archaeology ever was like that, but still where you’re out to find the gold statue, or the tomb.

Not to say that there are not archaeologists interested in finding a tomb, but it’s usually in the service of a broader sense of what that will tell us about the royal elite and how they ruled and changed or rose and fell. In my own area, how and why were the Maya—with a stone-tool technology—able to sustain a complex urban civilization for more than 1,500 years in a jungle environment with populations and agricultural activities that far outstrip what you see today with modern technology?

Our at-least partial failure is that we have not always been successful in communicating this intellectual excitement of the “new archaeology” to the public as much as the old adventure-archaeologist image from the B movies. Although I think we are starting to do a much better job, until recently there has not been the same appreciation. That’s changed—God knows, you turn on A&E, the Learning Channel, the History Channel, PBS and others, almost every night you’re going to find some focus on archaeology. Now some of that is the old traditional archaeology, but [in] a lot of it there’s a how or why question—even if it often has the word mystery in it, too.

We have much better understandings of ancient peoples, appreciation of their achievements, and I think in many ways have made their cultures relevant to society today. It may be heresy for a museum director to say, but my interest is not in objects. We have an important role in stewardship—in maintaining, studying, utilizing the collection—but the goal is ideas and understanding what the object can tell us, not the object itself. And I think that’s a very positive step.

How does this changed focus affect the exhibitions that the museum mounts?

Some of the great art museums have beautiful pieces, but they’ve often been acquired through gift or purchase where they’re not well-provenanced. You don’t have context. Since the bulk of our collection comes from our own research, one of the museum’s great strengths is that we’re able to talk a great deal about context.

Exhibits in the last decade are more idea driven, and they’re also trying to engage the viewer with the results of new scholarship. That’s something we try to do, though we still have a long way to go.

In the past there was a disconnect with the fact that we are doing research in 18 countries—that was not always well-reflected in our exhibits. It looked as if this was a museum that had done great things 40, 50, 60, 100 years ago. That’s why we have things like plasma screens to show all kinds of field and analytic work. We’re trying to do more, showing what our curators and senior research scientists are doing [both in the museum] and on the Web, through virtual exhibits. Even compared to 10 years ago—let alone what we’re talking about as the heyday of “romantic” archaeology—this is a much more dynamic and exciting place, with just all kinds of neat things going on across the board, in the field, in the lab, in the classroom, in the exhibit halls, in the storage areas, and now I think on the Web and in our publications.

How important do you consider what one might call the “public” side of the museum—bringing more people in and making it more attractive to school groups, for example, as well as to students on campus?

We have a number of initiatives to try and bring the general public here and also reach out to school children—more than 40,000 school kids come to the building each year. We also have programs like International Classroom and Museums on the Go that reach out to them. We also have the Commonwealth Lecture Program, where we provide lecturers to every single county in the commonwealth, that the state legislature helps support.

We want to bring the museum to the attention of the public, and the more people we can attract here the better, but we also realize that, in fact, a major traveling exhibit of ours might be seen by hundreds of thousands of people, and obviously virtual exhibits can be seen by millions of people around the globe. We also have a very active loan policy in which we loan our materials to museums both here and abroad.

As for students, another goal will be to integrate the museum more into the academic and student life on campus. I’m certain that this will be one of the charges of my successor. The Mainwaring Wing gives us the space to get students more involved in research. There are research rooms where undergraduates can do a senior thesis on aspects of the museum’s collection. We’re trying to do more lectures and programming that relate to student interests. There is an ancient-studies floor at Harnwell College House, for example. The Provost’s Council on Arts and Culture, which [Deputy Provost] Peter Conn chairs, was really something that I helped initiate and that I had been lobbying for almost since the day I arrived. Penn has incredible arts and culture resources but few appreciate the whole, and I think particularly with [Provost] Bob Barchi and Peter Conn’s leadership, the University has really taken the arts and culture to heart.

Whatever form this group takes in the future, there is now a central appreciation for arts and culture on campus, and there are things the many arts and cultural organizations can do in common in terms of marketing, of publicity, but also working with student groups. A lot of the arts and culture groups are either student-run or heavily student-invested—anything from the Writers House to all the theater, music, and so on. I think we can certainly strengthen our presence on campus working with other groups. Even though [the museum] has a strong role on campus, it is in many ways more visible off campus than on. Internationally, if you say Penn [people will think of] Wharton, maybe the hospital, or the museum. We are one of the most visible aspects locally, nationally, and internationally of the University.

You have to balance the scholarly and public sides of the institution. Are there tensions between them that need to be worked through?

Absolutely. And it’s still problematic, particularly for our curators. Half of their dutues relate to the straight academic side, the other half to the museum. Now a lot of the museum responsibilities are things that will support their academic careers in terms of tenure, promotions, and raises—but doing exhibits, doing a lot of public programming and outreach, the reality is that such activities do not have the same weight as publishing a book or a series of peer-reviewed articles. There’s always a worry of how to balance that, not only for the museum’s sake but also for the individual’s sake. I would like to find ways for that kind of public work—which I think is very important—to be given stronger weight in judging people’s careers.

I think there is a moral obligation for scholars, from the sciences to the humanities, to make their research understandable to the public—who, after all, support them. I think there is growing recognition in academia that this obligation is important. But I am encouraged that academic leaders in College Hall, such as [School of Arts and Sciences Dean] Sam Preston recognize the issues and are thinking about them.

After 9/11 and the invasion of Afghanistan, and again since the war in Iraq, the museum has taken an active role in providing background information on those cultures and also on the issue of looting of archaeological artifacts in Iraq. How do activities like those fit into the museum’s mission?

We’re talking about the relevance of the museum. We have scholars here very knowledgeable about Afghanistan, and so, after the invasion, we had public presentations that were very well attended just giving historical background on why Afghanistan is such a difficult political place. Why is it a place that the Taliban and al-Qaeda could have such a successful hold? And certainly with Iraq—a whole series of our scholars worked in Iraq in the pre-Saddam Hussein past—we felt that one of our public responsibilities with this situation was to try and be as helpful as possible in providing historical context for our audiences and advising on the archaeological problems there.

After the initial furor over the looting at the Baghdad Museum, we came to realize that the larger problem was the looting of archaeological sites throughout the country. Again we had a series of public presentations here. In particular, Richard Zettler, who is curator in charge of our Near Eastern Section, gave very well-attended presentations—we’re talking hundreds of people—on the current archaeological situation in Iraq. He and Steve Tinney [who heads the Sumerian Dictionary Project], offered a presentation up in New York at the Penn Club looking at ancient Iraq and relating it to modern problems, and Richard and I wrote an op-ed piece for the Inquirer. He has been on call to a number of agencies to give expert advice as well.

This is an example of where the museum can be very relevant and important by providing context for current affairs, but there clearly are lots of other ways where the museum is connected with present concerns. For example, Clark Erickson, who undertakes archaeology in Bolivia, is working with local farmers showing them how agricultural techniques from time periods centuries in the past were much more productive and efficient [“Gazetteer,” March/April 2001]. Working with some of the local farmers, he’s helping to make the agriculture today more efficient, based on successful techniques from hundreds and hundreds of years ago. He is trying to improve lives through archaeology, which might have seemed an oxymoron a decade or two ago!

This is another part of this new kind of archaeology—not that everything we do in archaeology and anthropology is relevant—but there is a very strong component of public-interest anthropology in the department here. The kind of work pioneered by biological anthropologist Frank Johnson on nutrition in West Philadelphia is an example. A lot of our scholars, both in the museum and certainly in the anthropology department, such as [Professor of Anthropology] Peggy Sanday and Paula Sabloff, are working with [Center for Community Partnerships Director] Ira Harkavy [“A Matter of Trust,” July/August 2003] in programs in West Philadelphia as well as on projects of their own.

So, the University Museum is not an old-fashioned, fusty museum of antiquities, but a dynamic place that is totally relevant—to the University and Philadelphia, in particular, but to national and global concerns as well. I’d like to think I’ve helped to further stimulate these developments, and I’m very optimistic that my successor will be able to come in and continue to foster those positive trends. Hopefully, 10 years from now that trajectory will remain on an upward climb.

I’m not going to say that I’m going to regret stepping down, because I’m looking forward to switching gears and getting back to teaching and writing, but at the same time it’s been a really incredible ride!