Advocates of religious liberty are grappling with a very complicated moment.

These are dire times for the free exercise of religion. Recent years have seen the Chinese government prohibit religious education for minors, going so far as to physically remove children from Easter mass services. In Burma, the militarized forces of Buddhist majoritarianism have sent hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims fleeing for their lives, and killed thousands more. Muslim-majority countries ranging from Indonesia to Pakistan to Egypt have imposed heavy restrictions on religious minorities and “heretical” sects. Meanwhile Tennessee Christians have tried to quash local mosque-building efforts, French police have fined and arrested Muslim beachgoers for wearing excessively modest swimwear, and US President Donald Trump W’68 has worked doggedly to honor campaign promises to enact a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.”

At the same time, some religious believers are enjoying a historic expansion of their ability to live by their convictions. The US Supreme Court has driven much of the action. In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014) it recognized, for the first time, a for-profit company’s claim of religious belief and held that such a claim could exempt a firm from certain government regulations that are binding upon other businesses. In 2018, the Court let stand a Mississippi law permitting citizens to refuse, on religious grounds, to provide services ranging from floral arrangements to facility and car rentals for any marriage-related activity involving people who are either gay or believed to have had premarital sexual relations. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has guided federal agencies to give similar deference to individuals and organizations who wish to “act or abstain from action” in accordance with proclaimed religious beliefs, asserting that Americans do not give up those rights by “participating in the marketplace, partaking of the public square, or interacting with the government.”

During the 2017–18 academic year, the Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy hosted a series of faculty workshops and a May conference exploring “The States of Religious Freedom.” The plural noun was a point of emphasis. With topics ranging from India’s recent tightening of laws against cow-slaughter (which has sparked fatal violence against religious minorities who do not share Hindu dietary prohibitions) to the asserted right of a Colorado baker to refuse to make a wedding cake for gay would-be customers (in Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission), the series underlined the diversity of contemporary debates about religious freedom.

On one end of the spectrum was Heiner Bielefeldt, a Catholic theologian who at the culminating conference delivered a philosophical and legal defense of religious freedom as a universal human right. It is fair to say that his views have been shaped by his six-year stint as the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief.

“When he travels to places like Bangladesh and Vietnam,” noted Heather Sharkey, a professor of Near Eastern languages and civilizations who chaired the series planning committee, “he’s still dealing with what now seem like old-fashioned religious freedom rights: of people just wanting to be able to either convert to [a faith] and proclaim it, or not to face coercion in conversion. I think he probably found it jarring to be dealing with people who see the cake case as a religious freedom right. It’s just so different.”

Joshua Matz C’08 [“Expert Opinion,” this issue], who coauthored an amicus brief for the Supreme Court in support of the gay couple in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, outlined a sea change in the nature of religious-freedom claims in the US.

“The most remarkable of these developments,” he said at the conference, “is the rise of complicity-based religious freedom claims—in which religious persons seek exemptions from, or accommodations within, neutral and generally applicable laws that were not enacted to target religion, and that don’t on their face target religion but, in the view of the religious objector, compel them to be complicit with the commission of sin.”

In the mid-20th century, Matz observed, some supporters of Jim Crow laws cited “God’s ordering of the races” to oppose the expansion of civil rights. But there were “exceedingly few claims of complicity of the kind we’re now seeing in relation to fairly similar antidiscrimination measures in the realm of gay and lesbian rights.” When one such claim did reach the Supreme Court, the justices “shot it down as essentially frivolous.” Yet today’s Court has opened space for such claims to thrive.

The rise in complicity-based claims has been accompanied by a shift in rhetorical strategies employed by religious activists—particularly those advancing conservative positions.

For most of the 20th century, such figures typically framed debates about religion’s role in American society in expressly moral terms. Some still do. “Conservative Christian leaders,” noted Marie Griffith, director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis, “have blamed feminism and the nation’s growing acceptance of homosexuality for the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Jerry Falwell), the theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado (Mike Huckabee), the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting (James Dobson), and more. Over and over, America’s ‘sexual depravity’ and embrace of various types of sexual ‘immorality’ have been held liable for horrific acts of violence that God has ostensibly refused to prevent.”

But the generation succeeding those aging figures has largely swapped morality-based rhetoric for appeals to individual rights—even when the policy goals remain the same.

The rights-centric approach has also gained traction with US courts, which have long declined to adjudicate questions of morality.

“Justifying the position of John Phillips, the cake baker who did not want to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding [reception], in the name of the need to protect the moral foundations of our society … would have no standing in today’s legal system,” noted Michele Margolis, an assistant professor of political science. But framing it instead in terms of infringement on an individual right afforded Phillips the “legal standing to challenge a law … he would not have been able to do previously.”

In the US, one result has been an expansion of what courts and some legislatures have been willing to consider as the scope and setting of religious activity.

In an earlier era, “we might have expected religious rights to ‘happen’ in places like churches and synagogues and mosques, and schools, and municipal cemeteries,” noted Sharkey. But the recent crop of Supreme Court cases has complicated the playing field. “If you go into Hobby Lobby, it’s a crafts store. You’re looking at multicolored pipe cleaners, and artificial flowers, and colored felt, and magic markers, and T-shirt decorating kits. You don’t imagine that that’s going to become the site of religious freedom battles.”

And those battles are increasingly hidden from public view, playing out “in somebody’s bedroom, when some employee at Hobby Lobby who may be making minimum wage doesn’t have access to contraceptives” that would be available to her if she worked instead at A. C. Moore (unless, of course, that corporation claimed religious objections too).

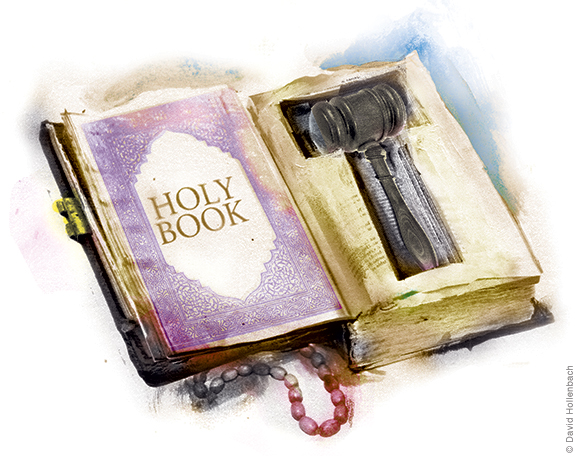

One problem with this enlarged conception of protected religious rights is that it brings free-exercise claims into direct conflict with other rights and responsibilities, such as the right of a law-abiding citizen to engage in commercial transactions without discrimination, or the responsibility of a county clerk to issue marriage licenses without discrimination as required by law.

“The mere possession of religious convictions which contradict the relevant concerns of a political society does not relieve the citizen from the discharge of political responsibilities,” wrote the late conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in a famous 1990 decision referenced at the conference by Matz. “To permit this,” Scalia continued, quoting a landmark 1879 decision against a Mormon seeking exemption from a federal anti-bigamy law, “would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself.”

Insofar as contemporary advocates of religious freedom are seeking to accomplish that aim, it could bring about consequences they may come to rue.

“Freedom of religion or belief is one of the most effective tools modern societies have ever developed for dealing with the inevitable tensions of life in societies with free and diverse persons,” declared Cole Durham, director of the International Center for Law and Religion Studies at Brigham Young University, at the conference. The case for viewing it as a universal human right, he argued, “derives precisely from its respect for particularity, and its recognition that protecting the dignity of difference is critical for [allowing] deep differences to coexist in stable and peaceful societies.”

Yet legislation like Mississippi’s Religious Liberty Accommodations Act inevitably reflects the influence of powerful religious groups—and can marginalize others. Mississippi’s law grants protection to three specific claims of religious conscience that happen to coincide with the views of conservative evangelical Christians, a powerful political constituency in the state. What does that precedent portend for Jews or Muslims or Christians who hold different beliefs with equal sincerity—or for secular citizens who bristle when religious claims are used as trump cards against their own interests?

“If proponents of religious freedom privilege religious rights over other rights—claims of secular conscience—then the prospects for constructive compromise are diminished,” said Rogers Smith, the Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Political Science.

No wonder, then, as Notre Dame religion and politics professor Daniel Philpott lamented, that “a phalanx of voices, including many prominent intellectuals, has been calling the principle [of religious freedom] into question—so much so that what was once a civilizational consensus now threatens to become a culture war.”

Indeed, religious freedom debates have been further complicated in many Western democracies by explicit appeals to “cultural heritage.”

The week before the conference, “the premier of Bavaria, Germany, Markus Söder, ordered that Christian crosses be erected in all public buildings in Bavaria,” noted Lori Beaman, a professor of religious studies at the University of Ottawa. “His justification was that ‘the cross is a fundamental symbol of our Bavarian identity and way of life’ and that the cross is a cultural rather than a religious symbol.”

Against a backdrop of falling levels of church attendance and self-reported denominational affiliation, and rising numbers of immigrants who belong to religious minorities, “Christian crosses and practices have been magically transformed into ‘culture, heritage, and a way of life’ in Italy, Canada, the United States, Australia, and France, among others.”

These actions have frequently originated with self-appointed champions of traditional religious majorities—and caused consternation among actual church leaders.

“The most outspoken opponent to the prime minister of Bavaria was the cardinal chairing the Catholic bishops conference,” Bielefeldt noted in a discussion period. “What he said was two things. First of all, it creates divisiveness: instead of the state opening up a space for religious diversity to unfold without discrimination and fear, here the cross is instrumentalized in order to shrink that space … so, in the favor of minorities: no to that. And second, it trivializes the cross by tying it to just a cultural symbol of national identity or regional identity,” divesting it of the deep religious meaning it carries for devout believers.

Yet the quandary remains: How can democratic societies best preserve space for religious liberty to flourish, without undermining the social comity upon which freedom of conscience ultimately depends?

No consensus emerged from the Mitchell Center’s yearlong engagement with that question. The closest thing to it was a wariness about an absolutist conception of individual rights as they pertain to the free exercise of religion.

“Ronald Dworkin and many others have long insisted that rights are not tools but trumps, absolute vetoes of policies that violate them—however beneficial the consequences of doing so might be,” Rogers Smith said. “Many critics of ‘rights talk’ contend—credibly in my view—that this kind of absolutist conception of rights can work against the willingness to respect and accommodate contrasting views that both Bielefeldt and Durham call for” as the sine qua non of religious freedom.

Smith suggested that robust and lasting religious freedom depends on the fulfillment of a crucial duty: remaining aware of “how imperfect our conceptions—much less our realizations—of that right” are, and “constantly vigilant about the dangers its pursuit presents.”

“It is only in a willingness to exercise permanent self-criticism,” Bielefeldt contended, “that freedom of religion or belief can be conceptualized and implemented as a universal right—or more appropriately, as a universal right in the making.” —TP