Three Penn alumni amassed three varied and valuable private collections, then bequeathed them to Philadelphia and the world. But what drove Mütter, Barnes, and Rosenbach?

By JoAnn Greco

Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

Imagine this. Two collectors meet at a dinner party. They enjoy each other’s company and embark on a brief correspondence.

In one letter, the book buyer, Abraham Simon Wolf Rosenbach C1898 Gr1901, comments on how the art aficionado, Albert Coombs Barnes M1892, had neatly organized the food on his plate. “Barnes writes back about how Rosenbach sort of inhaled his dessert as one, regardless of the separate components of cake, ice cream, and sauce,” says Judith M. Guston, curator and senior director of collections at the Rosenbach, the eponymous museum that he founded before his death. “Then Rosenbach sends another note that says something like ‘I would like to observe you again. Let’s have dinner soon.’”

Unfortunately, there’s not much evidence that the two Penn alumni ever got together after that. But those quirky exchanges delight our mind’s eye with their perfect encapsulations of the exacting scientist and the bon vivant bookseller. They also might lead one to think about what Philadelphia was like when Barnes and Rosenbach were at the height of their careers.

“In the ’20s and ’30s, the city is home to the precisionist art of Charles Sheeler and the International Style architecture of the PSFS Building and the modernist concerts of the Philadelphia Orchestra led by Leopold Stokowski,” points out David Brownlee, the Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor Emeritus of 19th Century European Art and a historian of modern architecture. “Philadelphia had become a significant center of modernism.”

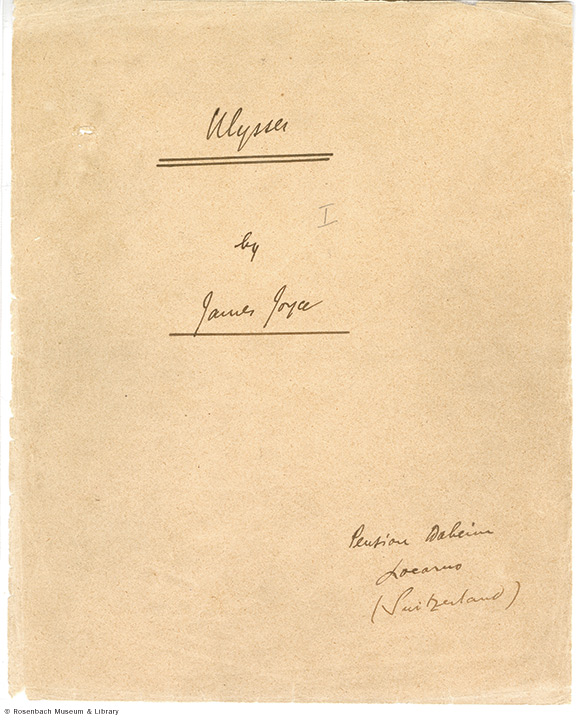

Rosenbach and Barnes were in the middle of it all. Soon after James Joyce published his groundbreaking novel Ulysses in 1922, Rosenbach placed the winning bid ($1,975—equivalent to roughly $35,000 today) for its original manuscript at auction. He brought it to his Rittenhouse Square rowhome, where it still resides as the star attraction at the Rosenbach. Also 100 years ago, pharmaceutical magnate Barnes was getting serious about his collection of controversial modern art and his theories about what that art meant, founding his own school and gallery in his Philadelphia Main Line mansion.

Preceding the chemist and the bibliophile in creating a signature Philadelphia cultural institution was another Penn figure, Thomas Dent Mütter M1831. Four decades before Rosenbach and Barnes, the extraordinarily handsome and stylish surgeon (as attested by contemporary accounts) had become fascinated with people deemed “monsters” because of their physical deformities. While introducing anesthesia to Philadelphia operating rooms and performing pioneering reconstructive surgery to help victims of disfiguring injuries, he too built a collection that grew into a museum bearing his name.

Though they were of a different generation, like Mütter Barnes and Rosenbach were grounded in the Victorian era and clearly influenced by its affinity for collecting and classifying. Each man changed how we recognize, understand, and value the beauty of books, art, and our very humanity. Each became famous during his life. Each rubbed shoulders with the elite but remained an outsider.

This is the story of how three “doctors”—two of them medical, one a PhD—made a mark on their time and place, then opened their unique, eccentric, and valuable private collections to the world at large.

A New Way of Healing

Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1811, Thomas Mütter endured a tragic childhood. Before he was seven years old, his infant brother, young mother, ailing father, and the grandmother charged with caring for him all died in rapid succession.

The boy’s fate changed, though, when he landed in the custody of a wealthy family friend and was sent to boarding school, before enrolling at Virginia’s Hampden-Sydney College, where he became a promising—and notably well-dressed—scholar. In Dr. Mütter’s Marvels (2014), author Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz lists the contents of one bill forwarded to his guardian: “a fashionable leghorn hat, several patterned vests, jackets and pants, yards of ribbons made from silk and velvet, several pairs of silk stockings.” His choices were “so flamboyant that the college’s theater department was known to have borrowed from his wardrobe.”

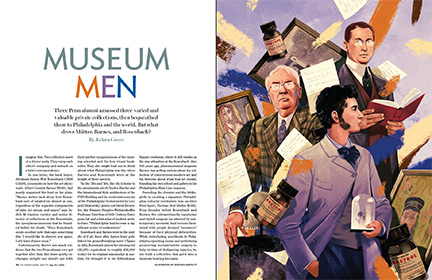

Always sickly—with what experts now believe was tuberculosis—Mütter was forced to leave college, but the caring doctors he encountered led him to consider apprenticing with a physician. A few years later, he entered Penn’s medical school, the nation’s first and most prestigious. “He’s like a flashing meteor,” says F. Michael Angelo, archivist for Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia’s second oldest medical college and Mütter’s professional home. “He finishes his MD at 20, by 30 he’s chair of surgery at Jefferson, and he’s dead by 48. With his appointment at Jeff, he sets out to build the best pathology collection in the country. He travels repeatedly to Europe to pick up specimens and casts of tumors and tissues, and teratoma.”

While in Paris, studying under the world’s most brilliant physicians, Mütter made his first such purchase: a wax cast of the face of an elderly French woman whose forehead sprouted a protuberance that over the years grew into a 10-inch, dark brown cutaneous horn. Mütter had recently learned about the new operations plastiques to reconstruct or repair ravaged faces and limbs using the patient’s own tissue, skin, or bone.

He returned to Philadelphia intent on refining and popularizing the experimental surgery to help patients disfigured by burns, knife attacks, and illnesses. Eventually he created what became known as the “Mütter Flap,” still in use to treat burn victims, which involves maintaining the grafted skin’s connection to its original site to ensure it retains its own blood supply.

At Jefferson, Mütter introduced other novel ideas into the operating room. One student noted that he appeared “to be painfully sympathetic with the suffering of the patient,” as evidenced by his practice of personally massaging his patients’ wounds for weeks before an operation(to relax the patient and desensitize the surgical site), insisting on sterile settings, and advocating for the creation of a separate post-op recovery wing.

Ignoring the scoffs of his peers, he became the first physician in the city to use ether while operating. “The amount of vitriol and conflict around anesthesia was staggering,” Angelo says. “The attitude often was God’s making you suffer for your sins. It’s not our business to remove pain from the procedure. Mütter was, like, What the hell? Are you kidding me?”

Mütter was becoming famous, but there was still a sense of not belonging. Though he earned a significant income, that proved “unhelpful in climbing the [social] ranks,” writes his biographer Aptowicz, since in Philadelphia “family had always been valued beyond wealth.”

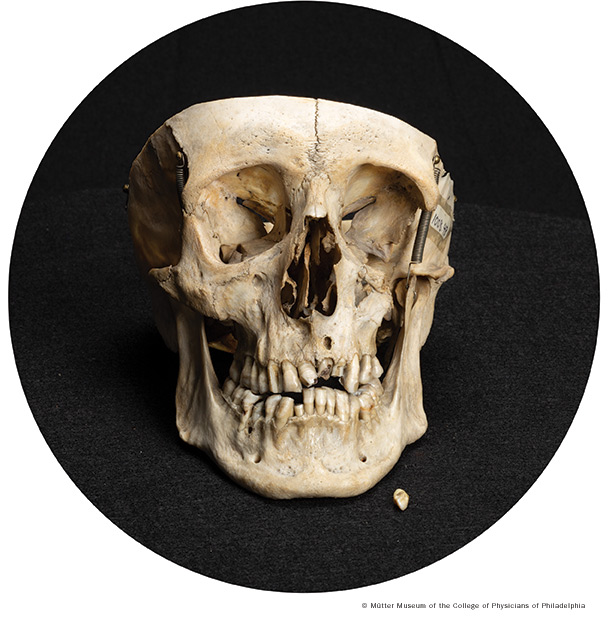

But he continued to advance as a surgeon, teacher, and collector, sharing his specimens of cancerous organs and disembodied appendages with his students at Jefferson. In a departure from standard lecture practice at the time, Mütter was among the first American professors to encourage students to actively engage with him by answering impromptu questions and repeating salient points.

His students included changemakers like Edward Robinson Squibb and Francis West Lewis. Compelled by Mütter’s early use of ether, Squibb devoted himself to fine-tuning its composition and application and founded the pharmaceutical company that would become Bristol Myers Squibb. A visit to the Hospital for Sick Children while accompanying Mütter on a trip to London helped inspire Lewis to establish the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 1855.

Mütter’s most obvious legacy, though, remains the museum. In 1856, at last giving in to his persistent ill health, Mütter resigned from Jefferson and began deaccessioning his library. He wrote a will leaving most of his personal effects to his wife, Mary, but more than anything wished to find a home for his collection of medical marvels. When Jefferson refused his offer—put off by his condition that a purpose-built structure be erected to house it—he found another taker in the College of Physicians, the nation’s oldest medical society.

According to Anna Dhody, acting codirector of the Mütter Museum, his 1,700 or so treasures form the base of an assemblage of more than 35,000 objects, including a piece of Albert Einstein’s brain, the conjoined liver of Chang and Eng Bunker, three vertebrae from the body of John Wilkes Booth, and a large tumor removed from President Grover Cleveland’s jaw. Today, medical professionals visit the museum. So do art students, literary scholars, and schoolchildren. “In many ways, teaching was as important to Dr. Mütter as surgery was,” Dhody says. “To see such a comprehensive museum come out of his private collection just furthers what he started.”

A New System of Seeing

Born into a working-class Philadelphia family in 1872, Albert Barnes showed an early interest in becoming an artist. But, intrigued by his science classes at the city’s Central High School, he instead decided to pursue a medical degree at Penn. Like Mütter, he finished by age 20.

The idea of practicing medicine never really appealed to Barnes, however. He switched to chemistry, finding a job at a pharmaceutical manufacturer and then leaving to partner with Hermann Hille, a German chemist he had recruited to join the drug company, to develop a less caustic silver compound than the one most popularly used as an antiseptic. Within a year, the two men found what they were looking for and named the solution Argyrol. Thanks to Barnes’ aggressive marketing, it was an immediate success. The partnership, though, floundered as Hille jealously guarded his formula and Barnes held tight to the company’s finances. When they parted ways, Barnes outbid Hille for control of the company (and its manufacturing methods) and rarely mentioned him thereafter.

Suddenly, the 35-year-old Barnes had more money than he could have imagined as a poor boy growing up in the Philadelphia slums. One of the first expenditures he and his wife Laura indulged was acquiring property in Merion, Pennsylvania. Feisty and cantankerous, he was not popular with neighbors. “For most of the Main Line’s well-bred citizens, Barnes was, and always would remain … a self-made businessman of no breeding,” writes Howard Greenfeld in The Devil and Dr. Barnes (1987). “Understanding that no matter how hard he tried, he could never break [that] barrier … for the rest of his life, he played the role they had assigned to him.”

Barnes started spending more of his money by building an art collection, first turning for advice to a former Central High classmate, William Glackens, an urban realist painter of the so-called Ashcan School. “Barnes has long sessions with Glackens and says, ‘OK, help me to understand why this painting isn’t that great, and why this one is so much better,’” explains Martha Lucy, deputy director for research, interpretation, and education at the Barnes Foundation. “He was a scientist, and he really wanted to understand. It became an intellectual pursuit, especially since this new work was being dismissed by the establishment.”

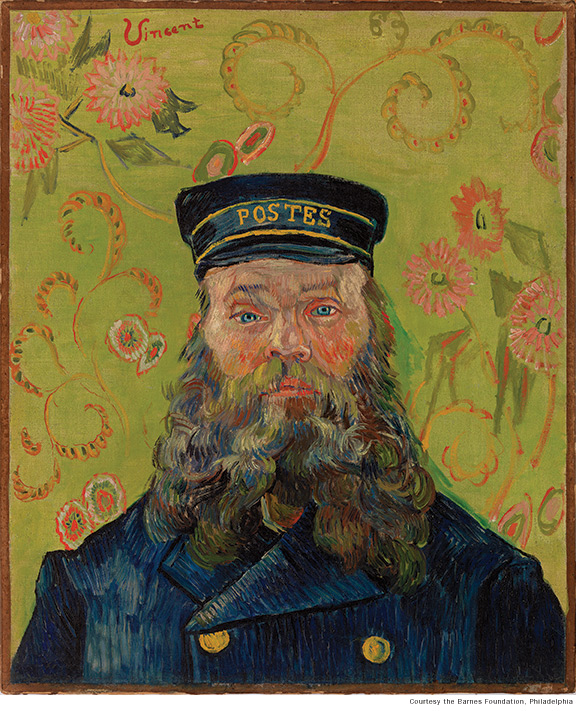

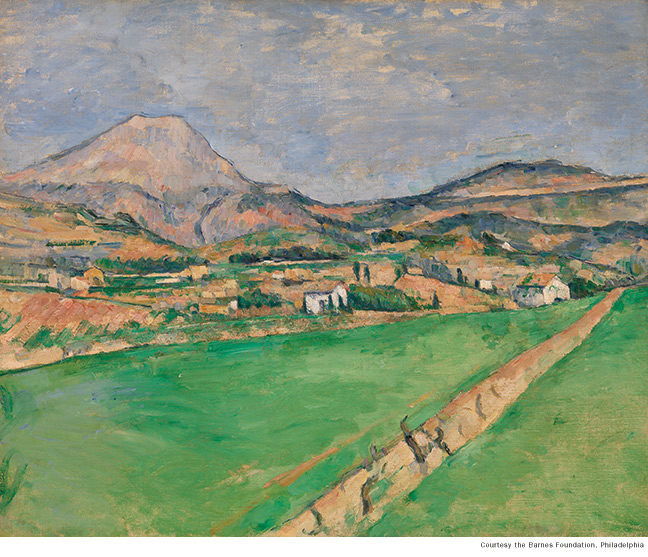

(Vers la Montagne Sainte-Victoire), 1878-1879.

The two wandered through galleries in New York and Philadelphia, and Glackens introduced Barnes to fellow artists like Charles Demuth and Maurice Prendergast. In 1912, Barnes dispatched Glackens to Paris, authorizing him to spend $20,000 on his behalf. The 33 works Glackens brought back include, according to his own written records, Vincent van Gogh’s The Postman (Joseph-Étienne Roulin) for 8,000 francs (estimated to have been $1,600 at the time); Paul Cézanne’s Toward Mt. Sainte-Victoire for 13,200 francs ($2,640), and Pablo Picasso’s Young Woman Holding a Cigarette for 1,000 francs ($200). They form the kernel of what would become the Barnes Collection.

Barnes himself started collecting in earnest that year, traveling to Paris repeatedly. “He bought voraciously … he knew what he wanted and quickly learned where to find it,” writes Greenfeld. “In the eyes of many Europeans … his methods reflected a lack of breeding and culture. He not only liked to bargain, but he enjoyed boasting of the [deals].”

At the same time, the collector also developed an interest in the writings of philosopher and educator John Dewey, whose “ideas on democracy and education really got Barnes going,” Lucy says. “The idea that art was not a rarified thing, separate from daily life and only understandable by the elite, was formative for him. It continues to be the mission of the Barnes today.”

After establishing his foundation and gallery in 1922, Barnes named Dewey as its director of education, giving the endeavor much-needed credibility. “In building the collection and chartering the foundation and displaying the work in the way he did, Barnes was determined to try to make art accessible,” says Lucy. The gallery wasn’t for the general public; instead Barnes invited specific groups to visit and began teaching from his collection. He even brought the paintings outside, to places like the Argyrol factory.

Barnes was a formalist, uninterested in the context of a work, approaching it purely from the impact of its visual content. He freely mixed art in different media—Pennsylvania Dutch furniture, sculptures from Africa—with his Renoirs and Cézannes, which were hung salon-style, paired by their dominant colors and the size and shape of their canvases.

“A huge sadness,” Brownlee observes, “is that his preeminent collection was so little accessed for so long that its impact wasn’t as great as it could have been.”

Barnes picked fights with the city’s biggest institutions—its newspapers, its art museums, and even his alma mater, Penn—up until his death in a car crash in 1951. More fights ensued—over access, finances, and whether the collection could be moved from Merion to a more central location in the city of Philadelphia.

Following a decades-long legal battle, in 2012 a new museum, equipped with modern amenities and up-to-date security and conservation protections, opened on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Serving a much larger public than had been able to view the collection before, it precisely replicated Barnes’ arrangement of the works in its original location. This year the Foundation is observing not only its centennial but the 10th anniversary of its new home.

A New Area of Collecting

The youngest of eight children, A.S.W. Rosenbach was born in 1876 and grew up bouncing around North Philadelphia, relocating as his father’s fortunes rose and fell. Like Mütter and Barnes, his professional fate was sealed early. His maternal uncle, Moses Polock, owned an antiquarian bookshop in the city’s Fishtown neighborhood, and the precocious “Abie,” as Rosenbach was called, was a frequent visitor and helper. Eager to participate more directly in the business of books, he attended his first auction at 11. “His enthusiasm … rather than his financial ability, swept him into the extravagance of paying twenty-four dollars for an illustrated edition of Reynard the Fox,” writes his close associate Edwin Wolf II in Rosenbach (1960), a florid, 600-page biography. After the sale, a sheepish Rosenbach confessed to the distinguished (and amused) auctioneer that he wasn’t exactly solvent, but the mention of his “Uncle Mo” garnered him a favorable credit arrangement.

It’s a pattern that repeated throughout his career as the world’s premier book dealer. “He’d buy these really expensive books and then immediately set to work making a list of potential buyers,” says the Rosenbach’s Judith Guston. “He seizes opportunities when they present themselves, he’s inspired and excited, and then he figures out what to do later.”

The only member of his large family to attend college, Rosenbach excelled in language and literary studies at Penn and was described in his yearbook—according to Wolf—as “a reading machine [who built up] such a fantastic store of book knowledge that he was able to tap the reservoir for fifty years.” Rosenbach “really knew what he was talking about,” adds Michael Barsanti Gr’02, a former associate director at the Rosenbach and now director of the Library Company of Philadelphia. “His clients trusted him to teach them about great books and their authors.”

When Moses Polock died in 1903, Rosenbach inherited his uncle’s stock and set himself up in the back room of his brother Philip’s antique shop on Walnut Street. Together, the brothers formed the Rosenbach Company, with Abie in charge of securing the rare books and Philip tasked with managing the financial ones. Armed with treasures including a first-edition King James Bible of 1611, an original letter from George Washington, and seven volumes of political tracts and pamphlets from Washington’s library, Rosenbach began calling on Gilded Age millionaires. In New York, none other than J. P. Morgan gave him his first four-figure sale in 1904, purchasing the bible for $1,750.

“Rosenbach entered the business when the great families in the United States were cash rich and book hungry,” says Barsanti. That included the wealthy Widener family of Philadelphia—particularly businessman and bibliophile Harry Elkins Widener. “Rosenbach nurtured him for years as he grew into a collector and the two became friends,” Barsanti continues. “In 1912, when Harry sails off to London with a shopping list, he sends telegrams back to Rosenbach, I bought this, I bought that, I’ll see you soon in Philadelphia. Well, Harry goes down in the Titanic. As a memorial to him, his mother asks Rosenbach to help her pull together a rare book collection from his personal library that she can donate in his honor to his alma mater, Harvard University.”

Rosenbach’s relationship with the blue-blooded Wideners was not typical, Guston points out. “He certainly did business with the robber barons,” she says, “but I wouldn’t say he was really welcomed into their society. He was Jewish and his father was an immigrant, so he didn’t have that background. He was seldom treated as a friend, but more as a respected consultant.” His sense of humor, salesmanship, and appetite for great stories made him the “influencer” of his day, she adds.

“He would get headlines in the papers and stories in the New Yorker for spending crazy amounts at book auctions,” says Barsanti. “He was the first to really believe in and promote the idea of a book, as opposed to, say, a painting or a piece of furniture, as being an object of worth and of possessing an aura.” Over the years, the rarities would come and go and sometimes come back: a Shakespeare folio, a handwritten Dickens manuscript, a Gutenberg Bible, a first edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

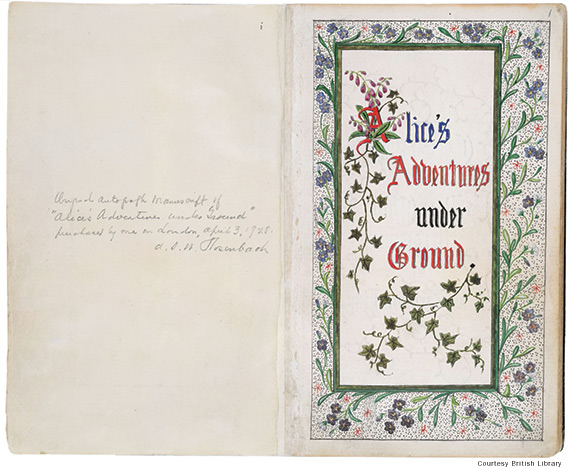

“The most famous purchase Rosenbach made in his lifetime was the original illustrated Alice in Wonderland,” Barsanti says. “It was put up for auction in 1928 by the woman who the character was based on. Rosenbach won it [for the equivalent of $1.2 million today] after the British Library quit bidding, then promptly sold it to Eldridge Johnson, who had become incredibly rich after selling his Victor [Talking Machine] Company. [Even though] Rosenbach was over-extended again and desperate to sell quickly, he still required as a condition of the sale that the book be put on display across the country.” After Johnson died in 1945, Rosenbach bought back the manuscript—and then presented it as a gift from the American people to the British Library.

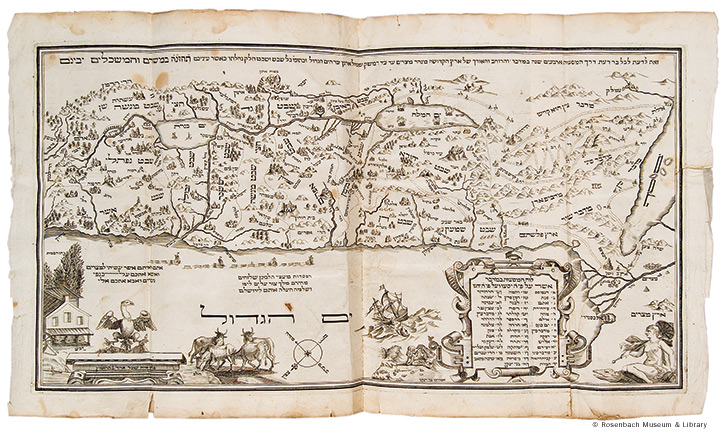

As he aged, Rosenbach became an increasingly active philanthropist. His post-World War II activities included working with Albert Einstein on establishing the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, donating his collection of children’s books to the Free Library of Philadelphia, and lending pieces to the Freedom Train, which set out from Philadelphia in 1947 to make whistle stops in the 48 contiguous states to showcase original documents. And, of course, he established the Rosenbach Foundation, which opened the Rosenbach Museum & Library in 1954, shortly after his and Philip’s deaths.

The Rosenbach’s mission, like those of the museums set up by Mütter and Barnes, has expanded over the years. Their audiences have become more diverse, and their paths have occasionally diverged from what their founders envisioned. But the spirits of these three men still linger. “We are committed to putting the objects they treasured and touched into the hands of the public,” Guston says. “We invite visitors to get close to them, to feel their history and authenticity, and to get excited about learning.”

JoAnn Greco writes frequently for the Gazette.