In a new book, artist and coauthor Lily Yeh brings the transformational power of art to a very dark place.

Lily Yeh FA’66 may be best known for cofounding the Village of Arts and Humanities [“Lily Yeh’s Art of Transformation,” Jul|Aug 2000], which since 1986 has renewed dozens of abandoned lots in North Philadelphia through an enterprising mix of neighborhood activism and public art. Trained in classical Chinese landscape painting, the Taiwanese-born Yeh spent nearly two decades at the Village transforming blight into beauty, a stint that brought her into the realm of large-scale place-making. Today she laughingly refers to that project as her “postdoc.” Since leaving her position as executive director in 2004, she’s found herself on a much more ambitious global stage.

“The Village taught me that forgotten ground can provide the nutrients for projects to unfold just as a tree of life does,” she says. More so than ever, her current work has a social and humanitarian bent, one that in accordance with Taoist tenets seeks to nurture into existence a “dustless” world, free of such pollutants as greed, selfishness, and violence, in areas that have been poisoned by them, emotionally, mentally, or physically. In 2002, driven by a belief that the “darkest places are most ready for transformation,” Yeh established Barefoot Artists, which has used the arts as a community-building and economic development tool in such troubled spots as Haiti, parts of India, and, most extensively, Rwanda.

In Surviving Genocide: The 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi (Shandy Press/Barefoot Artists, 2017), she and coauthor Susan Viguers combine Yeh’s artwork, photographs, and the words of the villagers of Rugerero in western Rwanda to document the building of a new memorial designed by Yeh. The effort was one of many in the area for Yeh, who estimates that she’s made about 10 trips there. Bringing together volunteers and villagers, Barefoot Artists has embarked on initiatives ranging from art projects to infrastructure programs aimed at strengthening the country’s recovery after it was torn apart by the 1994 genocide.

“I return when I can reap the most benefits and have the most impact,” Yeh says. “I have ideas all of the time, but I have to wait for the tree to blossom and the seeds to be set free.”

In assembling and editing the book, Viguers—a conceptual editor and book artist who has known Yeh since their teaching days at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts—culled through piles of material including videotapes, photos, and artwork. “Lily gathered and kept so much from these trips,” Viguers says. “We looked at many approaches, but in the end it was the stories of two people that particularly haunted her. ”

Uwicyeza Nzayisenga Angel is introduced in the book as “perhaps the most withdrawn, the quietest” of the 12 young women participating in a storytelling and drawing workshop that Yeh led. Viguers’ text relays how Yeh gradually comes to recognize the “terror behind Angel’s silence” after someone translates the text that Angel has scrawled next to the images. “This is a friend I was running away with,” Angel writes in describing one of her stick figure drawings. “They killed him and threw his body in the water.”

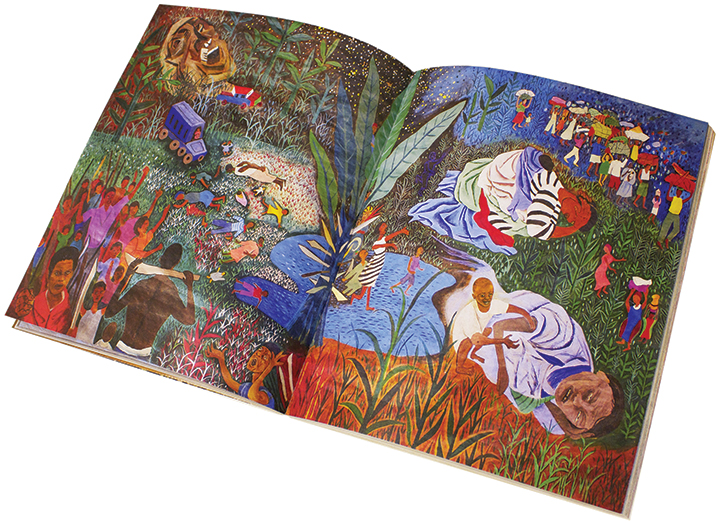

When Yeh returns a few years later to record an oral history, a weeping Angel at last breaks down and talks about the murders of her grandfather, parents, and brother. Near the end, with the young woman determined to locate her parents’ bodies so she can give them a proper burial, Viguers inserts a brilliantly hued fauvist painting by Yeh, one of three that appear in the book. It’s a nighttime image of machete-wielding men, bodies sprawled on the grass, and in one corner what appears to be a caravan of refugees carrying their belongings aloft.

Angel’s heart-wrenching story is followed by that of Musabyimana John Peter Sammy. “There was no one to comfort us,” he writes in the bundle of scribbled notes he gives to Yeh. “Everyone wanted to kill us.”

As his tale unfolds, the authors reveal that he and Angel are now married. “We met through our problems,” the text reads. “Now we have two children … After five years I got a job [and] my wife got a benefactor, Mama Lily, who helped her learn sewing. After the training, she gave her a sewing machine. She also gave us a water tank of 1,000 litres [and] started a micro-loan program. I was given a loan out of it.”

The simple language and spare line drawings interspersed through the narratives—Yeh’s interpretations of the stick figures drawn by the women in her workshops—might lead one to wonder if the book is intended for young readers. “This combination of text and colorful images is something that adults aren’t used to,” concedes Viguers. “But obviously this is very dark material, given beauty and life—it’s not for children.”

Angel and Sammy’s stories are bracketed by two photo essays. The first offers some context for the war and explores the community’s participation in building the new memorial. The second covers the dedication of that memorial, which was unveiled in April 2007 in time for the nation’s national day of mourning.

Yeh’s installation bears the trademarks of her Village work—mosaic art, Tree of Life imagery, and painted stucco walls—and replaces the rough-hewn concrete and timber structure that had served as an unmarked and unsatisfactory mass gravesite. “I was moved by the suffering of the people; that’s all,” Yeh says. “I didn’t think about good and evil but about encouraging the transformation of a community.”

For Yeh, art is ultimately not just for the viewer but for the doer—and that includes herself.

“I want to experience fulfillment in my own life,” she says. “I’m always looking to find a place where I can go into the depths of human life and, through working together, change things. I go to places where this alchemy of turning lead into gold can happen, where there’s enough sunlight for the roots to flourish and the tree to grow.”

—JoAnn Greco