Dissatisfied with her work as a painter, Lily Yeh was searching for “a luminous place, a place where I could locate the sacred in the mundane”—and found it in blighted North Philadelphia.

By Phil Leggiere | Photo by Candace diCarlo

Before emerging as one of America’s most innovative urban designers and, many believe, social pioneers, Lily Yeh FA’66 spent much of her young adult life struggling uneasily in the interzone between disparate cultural traditions and identities. Born 58 years ago in pre–communist China, Yeh grew up in Taiwan as the daughter of an army general. She was just out of her teens when she was uprooted from the social, aesthetic and spiritual world she’d known, emigrating to the United States in the early 1960s to attend Penn’s Graduate School of Fine Arts.

At Penn, under the tutelage of a faculty that included such luminaries as professors Jim Van Dyck, Angelo Savelli and fine-arts director Malcolm Campbell, Yeh experienced an intensive initiation into the techniques, history and aesthetics of classical and modernist Western art, a process she found both exhilarating and “profoundly disorienting,” she says.

“I had started painting when I was in junior high school, when my father, who loved classic Chinese landscape painting, first took me to a master’s house. The way we learned in China was by strictly copying our masters and studying nature. Personal expression was not encouraged,” she explains. “When I came to the States, though, it was all free-style, abstract and geared toward expressing personalities. In this urban world, no one knew or cared about landscapes. I’d been catapulted across time. I felt like a woman with bound feet, and I couldn’t walk.”

Yeh spent several years adapting, with some success, to modernist Western art, “forgetting all about brushes and landscapes,” working her way into galleries and museums in Philadelphia and other cities by painting in more fashionable contemporary styles. She also earned a plum teaching position at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. Though excited by the possibilities of the new world she’d discovered, she knew there was something she’d lost. “I enjoyed working in the gallery scene, but I could never really give myself over to it,” she reflects. “I was still seeking something else, something that Chinese landscape painting had instilled in me, which was the sense of what the tradition calls a luminous place, a place where I could locate the sacred in the mundane.” She had, she gradually realized, become accomplished as a painter, but was still not yet an artist.

Crossing that most subtle border from painter to artist entailed still another life-changing journey for Yeh—a spiritual emigration of sorts, as she describes it. And a most unexpected one by art-world standards. Though she didn’t realize it at the time, it would involve a move away from creating paintings as commodities for galleries and collectors to a new kind of art rooted in a sphere considered alien to art.

Geographically, North Philadelphia is less than two miles from the Center City bistros, galleries and art schools around which Yeh had lived in the 1970s and 1980s. Socially and culturally, though, it’s a world apart. Once a vibrant manufacturing center, the primarily African-American neighborhood, decimated by a generation of disinvestment, by the mid-1980s had unemployment rates exceeding 30 percent and a median household income of under $10,000—less than half that of the rest of the city. Two-thirds of North Philadelphia households lived below the federal poverty level, and nearly one-third of the neighborhood’s properties were vacant.

Yet it was to this neighborhood that Yeh became drawn in 1986. Ironically, the catalyst bringing her to North Philadelphia was a series of visits to China she had made in the early eighties.

“It really is through China that I came into contact with the neighborhood, which is a strange coincidence,” she says. “I’d been helping the city of Philadelphia to establish a cultural exchange with Chinese artists. So when China sent three delegations here they asked me to help them.”

One of Yeh’s roles was to show the visitors African-American artistic accomplishments, specifically the work of Arthur Hall. Hall, a cultural impresario and mainstay of the North Philadelphia community, had been living in the 2500 block of Germantown Avenue since the late 1950s. In the 1960s he had launched a dance ensemble and African-American cultural center which for years had brought dance, theatre and visual arts to the area. By 1986, though, federal and state budget cutbacks had taken their toll on the project.

“I’d known Arthur and admired his work,” Yeh remembers, “but real contact began then. He’d seen some of my gallery installations of indoor gardens and told me about an abandoned lot next to his building, mentioning that it’d be great if somebody came up there to create an outdoor garden in that spot.”

Thus began “Ile-Efe,” Yeh’s first North Philadelphia project, and the one which, she now believes, brought her experience as an artist full circle. “When I started work on that abandoned lot, I was mighty scared,” she admits. “I was a Chinese woman from the outside with no knowledge of how to build a park. Friends had said that my work would be destroyed because of tensions between Asians and African-Americans. I wanted to run away, but there was a voice inside me that led me on.”

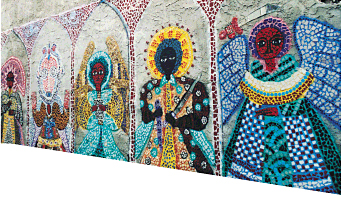

It was in this context, Yeh recounts, that she learned the value of humility. “Since I knew nothing about the neighborhood I had to learn to ask people to help me. I needed to engage the neighborhood, the children and also the street people and drug users who hung around the block.” With their help Yeh transformed what had been for nearly a decade a visual blight into a colorful park, decorated with murals of guardian angels designed to protect the block—surrounded then, during the height of the crack epidemic, by open-air drug bazaars—from dangers.

One person who was key to Yeh’s overcoming her isolation was JoJo Williams, a local who, though unemployed and a drug addict, possessed, she says, “a fiery, friendly spirit.” For small stipends of five or ten dollars Williams began helping Yeh clear out the rubble and debris from abandoned lots, becoming in the process her “protector,” and a legendary force in the neighborhood until his death from cancer in 1995.

Williams supported Yeh not only through physical pick-and-shovel labor, but by becoming her conduit to other kindred spirits who would give her work core support. Prominent among them have been James “Big Man” Maxton, a 6-foot, 8- inch tall neighborhood drug runner who soon blossomed into an energizing organizer of community renovation efforts, and a skilled mosaic artist and craftsman himself; Deborah “Mama Debbie” Maxton, who helped organize efforts to teach arts to children; and H. German Wilson, whose theater programs have been perennially popular with Philadelphia youth.

Ile-Ife was supposed to be a one-shot deal, a temporary detour from Yeh’s gallery-centered career. “I didn’t plan to stay,” she confesses. “I wanted to move on with my career, but it took hold of me. I couldn’t forget that place. It wouldn’t let me.” For a long time, she adds, she had been “poking around, trying to re-connect to the transcendent place I believed art was supposed to reach. I’d never been able to really paint that place, but by physically creating a community garden I began to connect there again. North Philadelphia gave me the opportunity to see again. I think it’s because in broken down places spirits are more open.”

What followed over the next several years, as Yeh began to base herself in the neighborhood, was the founding and flowering of The Village of Arts and Humanities, an effort unique in the annals of both contemporary art and community activism. Yeh, along with an expanding crew of volunteers, and more than a dozen full-time paid workers, including neighborhood people, college students and visiting artists from Philadelphia and around the world, embarked on efforts to transform what’s come to be called the “Village Heart,” the four block area bounded by Germantown Avenue on the east, Huntington Avenue on the north and Cumberland Street on the south.

Spreading outward from this core into a wider 20-to-30 block area she calls “The Village Neighborhood,” Yeh and her cohorts have transformed more than 120 abandoned lots—with, she’s convinced, more to come. “What I’d like to do,” she declares, “is to revive every abandoned lot and building in the 260-block area encompassing North Philadelphia. We want to turn decimated areas into meadows, wildflower fields, urban tree farms, and mixed-use offices, educational facilities and low income housing.”

Yeh’s work at the Village renegotiates the boundaries of many artistic disciplines, not only mural painting and sculpture, but architecture and urban design as well. “I’ve come to conceive of the Village as a living piece of sculpture,” she explains, “in which sculpture is a communal event. The walls are all shaped and touched by people’s hands, including as many people from the community as possible.” Though this unconventional, multi-faceted approach flies in the face of business-as-usual in the city-planning profession no less than in the art world, it is gradually gaining a core of admirers.

“The dominant style and instinct of urban planners,” observes Sally Harrison, professor of architecture at Temple University, whose main campus is in North Philadelphia, “is still to come into a blighted area with the idea of just clearing away the old and re-making it with a brand new concept. What’s so striking about Lily’s vision is that, with far fewer resources at her disposal, she takes an organic, evolutionary approach to rebuilding, finding the seeds of the new within the old, working with the natural fabric of the environment.”

Unlike mainstream architects, who build on the basis of their own conceptions and blueprints, Yeh’s vision of neighborhood development emerges from the bottom up, lot by lot and block by block. As she describes the process, “People will come to us and tell us about an abandoned property on their block. We then hold a block meeting and come up with a view of how they want that space used.”

The spaces are meant to be aesthetic objects, integral parts of the physical and emotional tone of the neighborhood. Even more so, however, they are created as a means of mobilizing people in the neighborhood to create “community wealth” and bring jobs into the community. “We want to create meaningful jobs,” Yeh insists. “Not just McDonald’s jobs, but jobs based on community enterprises.”

Accomplishment of that goal means providing neglected youth with skills, as well as the confidence to prepare them for a global knowledge-based economy. Yeh believes that, here too, the arts can play a crucial role. In partnerships with several area public schools, The Village has developed a program called Education Through the Arts. “This is not just arts education as usual,” Yeh emphasizes, but a new methodology using the arts to foster a wide variety of cognitive and other skills.

At the Hartranft School at Eighth and Cumberland streets, three blocks from The Village, for instance, Yeh and other staff members have used the arts to work with K-5 students with learning disabilities in reading and writing. They used the motif of angels, according to Yeh, “because the children live in a dangerous place and need security.

“We talked not just about the standard angels in church,” she adds, “but angel figures from all cultures, Assyrian, Mesopotamian and Buddhist. Once we excited their imaginations they began creating their own angels. Before that, the children were afraid to speak and learn because their creativity was all bottled up. But in talking about their personal angels they came up with all these wonderful lines. Before this, the children had trouble writing, but we told them to just speak and then we recorded their talk, transcribed it and gave it back to them. Pretty soon it becomes much easier for them to write and read because it’s their own words.”

Dr. Michael Kolakowski, principal of the Hartranft School, says both the children and teachers were impressed. “You can measure the difference The Village has made,” he explains, “by the fact that year after year, for seven years now, the kids always ask when Miss Lily will be back.” More generally, Kolakowski observes, The Village has given the area a dramatic physical and emotional makeover. “When all you’ve known is blight you get used to seeing only blight. Lily teaches the children that you don’t have to only see blight. She’s taken a whole city block between 10th and 11th on Cumberland, where before there was only decay, and turned it into something not only beautiful but [which] we now use as an outdoor classroom.”

In addition to educational partnerships, The Village also has launched initiatives in nutrition and preventive health care, neighborhood-based craft industries and urban gardening. Over the next few years Yeh also plans to establish a “Village on the Move” program in which ongoing workshops will be held in tents set up at five locations around North Philadelphia.

Though all observers seem to agree The Village has made a difference in the physical look and spirit of the neighborhood, skeptics do question how much such inspirational projects can accomplish without more fundamental economic changes. Yeh acknowledges that The Village alone can’t solve the deep economic and political problems of the area. “What we can do,” she insists, “is change perception, and through that change the condition of hopelessness which has prevailed.”

Another key unanswered question is whether The Village, as the singular vision of a charismatic founder, can be sustained when she’s no longer around. “I’m still as excited about the work we’re doing as I was when I arrived here 14 years ago, and there’s so much more to do,” says Yeh. At the same time, she adds, “I have other places to go as well,” referring in particular to Korogocho, a village in Kenya where she has initiated a pilot project modeled on her work in Philadelphia.

Though she intends to stay closely associated with The Village, Yeh is considering stepping aside as executive director “in about three years or so” to make way for a new generation of organizers whom she has trained. “They’re motivated, sophisticated people who are bringing in a serious professionalism and talents for order and efficiency I never had,” she says. With them, Yeh looks forward to expanding The Village’s range and scope, as well as putting it on more solid financial footing. In order to fulfill that goal she is, as she puts it, “trying to learn some new languages, new ways of defining and achieving our goals.”

One new means is high technology, specifically the World Wide Web, through which the possibility exists for the first time to link kindred grass-roots efforts around the world, allowing them to find ways of joining forces. Yeh is also trying to learn new ways of economically maintaining The Village without relying on grants, by developing self-sustaining non-profit and for-profit community-based businesses, an approach known as “social entrepreneurialism.”

She is currently seeking the advice of sympathetic, socially responsible corporate leaders such as Con Kenney W’80, director of re-engineering at Fannie Mae, on how to adapt some of the planning tools, strategies and intellectual disciplines of the corporate sector to advance the Village’s cause. Successful grass-roots projects like The Village should be seen as crucial “incubators of social innovation,” Kenney says. “There’s an emerging consensus that technocratic interventions from afar have failed to really impact social problems in a deep and abiding way.”

“Without planning it,” Yeh believes, “we’ve actually been doing, in the shadows, what governments and corporations want to see done. They need skilled people and strong, stable communities, but they don’t know how to bring that about.”

Soon after his election, the transition team of Philadelphia’s new mayor, John Street, visited The Village to study its approaches to neighborhood revitalization. Mayor Street himself professes to be a fan, saying that Yeh’s work “clearly demonstrates the power of community development,” and adding, “I think Lily is one of our city’s great treasures.”

Intellectual and political capital will be important in making the kinds of innovation unleashed at The Village thrive, but even more important in the long run, Yeh concludes, will be a resource which, though theoretically unlimited, is often hard to come by: humility.

“Professionals need to go out to the field, not with the attitude that they’re going to come in and take things over because they know more. They need to learn the art of listening. Community speaks eloquently if you give it a chance, and if you can do that, magic can happen.”

Phil Leggiere C’79 is a freelance writer based in Hoboken, N.J. He last wrote for the Gazette on Internet entrepreneur Elon Musk C/W’95.