Julian Siggers’ tenure as the Williams Director of the Penn Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology has seen some high-profile, groundbreaking exhibitions: Native American Voices: The People, Here and Now, on Native American culture past and present [“Know That We Are Still Here,” Jul|Aug 2014], and the The Golden Age of King Midas, featuring artifacts from the long-running Gordion excavations in modern-day Turkey [“Beyond the Golden Touch,” May|Jun 2016], to name just two. Public outreach has expanded as well, from programs like “Unpacking the Past,” which is aimed at middle-schoolers [“Making Mummies—and Museum Goers,” Jan|Feb 2014], to a lecture-and-discussion series examining the issue of race from multiple perspectives, to music performances in its galleries and garden.

As Siggers passed his fifth anniversary in the position on July 1, the Penn Museum was poised to launch a renovation project that represents a “profound change to the way it presents itself to the public” and an “incredible opportunity to relaunch the Museum,” he says.

Dubbed “Building Transformation,” the estimated $80 million multi-phase effort—which follows on earlier projects like the “big dig” under the pond outside the main entrance in preparation for installation of new HVAC facilities and the renovation of the Museum’s west wing completed under previous director Richard Hodges—will air-condition and fully renovate the venerable Harrison and Coxe wings (completed in 1915 and 1926, respectively); reconceive and upgrade existing galleries for Egypt and Asia; and create new galleries focusing on the ancient Middle East, the vibrant mix of cultures along the coast of ancient Israel, and the origins of writing.

According to a project description, the “transformation” will involve both extensive physical upgrades and changes in how the collections will be presented to visitors: “through a spotlight on objects that are rightfully world-renowned, through digital technology, through other touchable or interactive exhibits, through an emphasis on ongoing research that brings the thrill of discovery right into the galleries.”

Work on the initial phase, for which $28 million has been secured, will start in November and run through spring 2019.

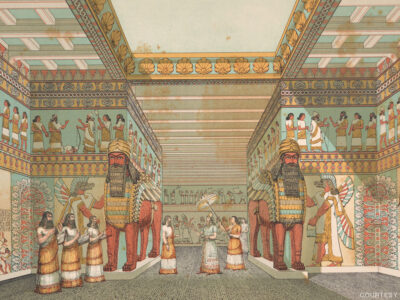

First up will be the 6,000-square-foot Middle East Galleries, which will be installed in already renovated space that formerly housed the King Midas show, which closed last November. Siggers describes it as “our sort of beacon [showing] what this museum will look like.” That exhibit is scheduled to open in April 2018.

The first phase involves a major reconfiguration of the space beyond the Museum’s main entrance, currently taken up by the gift shop and a staircase down to Harrison Auditorium. In place of the old stairway, two grand staircases from the original 1899 building located to the right and left of the entrance that had been closed off will be reopened. Harrison Auditorium and the lobby area will also be restored and all facilities made ADA accessible. New restrooms and elevators will be installed there and in the Coxe wing. And the entrance to the Egyptian Gallery, currently a bit of a secret passage at the rear of the gift shop, will be widened and enhanced with floor-to-ceiling windows.

“We’re basically opening up a hinge there,” Siggers explains. “There are three new elevators and another stairwell, so it will be a much wider, more generous entry.” The alterations will also “clean up” the space beyond the entrance. “That front area is so messy when you walk in. It’s very, very cluttered, visually.”

A new “Crossroads of Cultures Gallery” will be installed in the fall of 2019 in the newly cleared area. Serving as a kind of orientation to the Museum and an introduction to the ancient world, the gallery will showcase artifacts from the Museum’s excavations in Beth Shean in current day Israel while exploring the coast of Israel as “a hub of cultural exchange and creativity for the last 10,000 years.”

In the project’s second phase, for which fundraising is under way, Siggers says, the Museum’s Egyptian collections will get climate-controlled storage for the first time, and the Lower and Upper Egyptian Galleries will be extensively renovated. A fall 2020 start is projected.

The “crowning glory” of the latter gallery “will be the restored throne room of the Palace of Merenptah, which I think is going to be one of the most staggering galleries anywhere in the country,” Siggers says. The plan calls for moving the Palace’s 15-ton stone columns from the Lower Gallery—where they could only be shown in sections—to the higher-ceilinged Upper Gallery, where they can be be presented in their full, 40-foot height, “as they were meant to be,” says Siggers. That represents a tricky engineering challenge, both in terms of the logistics of placing the columns and reinforcing floors to ensure their weight can be supported, he notes. “There will be all sorts of simulations before we actually move these up.”

The project’s final stage, anticipated to begin in fall 2021, will see renovations to Pepper Hall (where the new gallery on the origins of writing will be located) and the Chinese Rotunda, and the installation of new galleries for Buddhism and the history of China. Siggers calls the Rotunda, with its iconic 90-foot dome, “one of the great architectural masterpieces on campus,” but one that also “presents a fundamental challenge: because of its grandeur, when you walk in, your eyes are immediately swept upwards. And it sucks drama and impact from the objects.”

The two massive 15th-century Buddhist murals that have long hung on the Rotunda’s walls are “the only works that could really stand out in the space,” Siggers notes. One fix being considered to enhance the impact of the collection of primarily Buddhist objects to be exhibited in the space involves slightly darkening the windows and using powerful pinpoint lights to illuminate the objects. The lights would be mounted on a ring that could be lowered from the top of the dome. Planners are also looking into some unobtrusive methods of taming the Rotunda’s notorious acoustics.

Before joining the University, Siggers was vice president of programs, education, and content communication at the Royal Ontario Museum, and striking the right balance between the Penn Museum’s intellectual and public identities is never far from his mind. “At our heart, we’re a research and teaching institution,” he says. “But this museum is unlike other university museums because of the scope and quality of its collection. When you have collections like this in your care, you have a responsibility to the campus, first and foremost, but you also have a responsibility as part of our university to engage with the public.

“I think one of the most exciting things about museums of archaeology is the archaeologists and the work they do,” he adds. “Galleries that are full of the wonder of discovery and [that make] you see the world in a different way are not incompatible with what our faculty curators do every day with their students.”

More broadly, museums must evolve in response to social realities. “More than ever before there is competition for people’s time—there are many other things to do than to go to a museum on a rainy afternoon,” Siggers says. “And so we do try different forms of programming—like having live entertainment in the Trescher Courtyard during the summer—to find ways to bring in people who wouldn’t normally go to a museum but who, once they are here, will go, ‘Hey, this is pretty interesting. I think I’m going to come back.’”

The toughest demographic are young adults, from “18 to when they have kids,” Siggers says. “When people have kids, the museum clicks back in. But that little window is difficult.” At the same time, he adds, “there is a real thirst for knowledge” among the general public. The Museum’s Wednesday evening “Greats” programs—as in discoveries, journeys, etc.—regularly bring in 500 people, “which is amazing.”

Last fall’s “public classroom” project, Science and Race: History, Use, and Abuse, “came out of a very interesting discussion within the Museum where we felt—as not just an archaeology museum but an anthropology museum, too—that the topic of race is so fundamental, particularly now, that we should do something to address it.” The initial thought was to mount an exhibit, but “it became very clear to me that an exhibition is not nuanced enough to explore race. It is too charged. And so we looked for different ways to do it.”

The program involved a series of workshops including introductory lectures and extended panel discussions with leading experts at Penn and elsewhere on various aspects of the issue, Siggers says. “We’re looking at race and genetics, race and the history of science.”

The events were live-streamed and archived to reach a broader audience. “We [thought if we] could also provide school teachers with tools and a website that they could continue to use in their classroom, that’s probably the best way to dig into this subject,” says Siggers. “And I’ve been really pleased with its outcome—because, you know, a whole church congregation, because it’s live-streamed, will watch it and then use it as a springboard to have a conversation within their congregation. Which is exactly what we were after.” (See more information and videos at www.penn.museum/sites/pmclassroom.)

The Museum still supports excavations around the world—22 in Summer 2016, Siggers notes—through the Director’s Field Fund and another endowment. “In some of those we’re just providing the seed money, and they’re filling it out with foundation stuff.” Discovery is what “keeps this place alive,” he adds.

To “back away” from research, as many museums have, “I think is a grave mistake,” Siggers says. “It’s the research and the teaching that provide the dynamism for a museum. I love the fact that, at the end of the summer, all these teams come back to the Museum [and say], ‘You’ll never guess what we found.’”

Notably absent from the Museum’s facilities planning is any expansion of the building footprint. “One of the things I was very keen on was to largely work within the envelope of the building. In the 2000s we saw many museums embark on ambitious additions—with concomitant increases in their operating budgets,” Siggers explains. He considers the existing space “appropriate for the collections.” And while dealing with older structures certainly adds to costs—“You could probably rebuild the Museum from scratch with less money than it’s going to take us to renovate what we’ve got,” he says—the Museum itself is a historical artifact. “One of our curators thinks that the building, in fact, is almost the most important art object we have in our care,” he says.

The new plan also makes a point of showcasing the Museum’s own collections. “I made a fairly conscious decision, along with the executive team here, to focus on our own collections,” Siggers says. “When you have over a million objects in your own care, from every part of the world, from Alaska through to Oceania, all of the building blocks for fantastic narratives are right here.”

“This is a wonderful moment in this museum’s history. I really think we will fulfill our ambitions,” Siggers says. “And I think this museum has the potential to be an absolute must-see destination in Philadelphia. I mean, the objects here are so spectacular, they are so globally significant to the human story that, if we do this right, everybody who comes to Philadelphia won’t just want to go and see the Barnes and the PMA. They’ll say, ‘We have to see the Penn Museum.’” —JP