There’s a lot more to King Midas than history’s most celebrated case of “be careful what you wish for.” Drawing on decades of excavations at Gordion in modern Turkey, a blockbuster exhibition at the Penn Museum illuminates the world of ancient Phrygia’s greatest ruler.

BY JULIA M. KLEIN | Photography by Candace diCarlo

As king of Phrygia at the eighth-century BCE height of its power, Midas loomed large in the mythology of neighboring Greece and Rome.

Or one might say that he loomed small—a popular figure of fun, mockingly enshrined centuries later as an exemplar of stupidity and cupidity in the Latin poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. A case in point: Midas was reputed to have acquired donkey ears when he made the mistake of ruling for Pan rather than the more powerful Apollo in a musical contest. More famously, when Dionysus granted Midas’s ill-considered wish to have a “golden touch,” the king faced the threat of starvation from unexpectedly gilded food.

But it turns out the myths don’t do Midas justice. His contemporary Assyrian rivals, whose writings are the principal historical sources on his reign, had a more respectful, if wary, view of the man they called Mita. Their annals describe him first as a foe, fomenting insurrection in the Assyrian-controlled states bordering his kingdom, and later as an important ally. “They were exasperated by him, they feared him, and in the end Midas established diplomatic relations with Assyria, so they liked him,” says C. Brian Rose, curator of the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s world-exclusive exhibition, The Golden Age of King Midas.

The show, on view through November 27, capitalizes on the myths and speculates on their origin. But it also presents considerable archaeological evidence from the ancient capital of Gordion, about 40 miles southwest of Ankara in modern Turkey, of the king’s energy and ambition. Its centerpiece is a gallery designed to suggest the earth-covered wooden tomb Midas constructed around 740 BCE for his father, Gordios—a burial mound that, at 174 feet, remained the most imposing such monument in Asia Minor for nearly two centuries.

To the delight of Penn’s excavators, the royal tomb was found intact in 1957. Within the so-called Midas Mound lay a skeleton, fragments of a gold-colored shroud, and hundreds of wooden and bronze objects, including finely wrought vessels still containing the remnants of a funerary feast.

With 230 artifacts in all, The Golden Age of King Midas invites contemplation of Midas’s power, the mutability of reputation, the long-term commitment of Penn to this rich Turkish site—and the ability of archaeology to re-create, in imaginatively stirring ways, an otherwise inaccessible past.

“We regard the exhibit—indeed all our exhibits at the Penn Museum—as the public performance of our research,” says Rose, the James B. Pritchard Professor of Archaeology, the Peter C. Ferry Curator-in-Charge of the museum’s Mediterranean Section, and director of the Gordion Archaeological Project. Launched in 1950, the Gordion excavations constitute the museum’s largest and longest-running archaeological enterprise.

Rose says he began his efforts to mount this exhibition in 2008, with the idea of a 60th anniversary show in 2010, but “underestimated the amount of time that was necessary to put a show this ambitious together.” One major hurdle that had to be overcome was a dispute over whether certain gold artifacts in the museum’s collection may have had Turkish origins, which delayed the signing of an enabling agreement with the Turkish government until 2012.

In historical sources, Gordion was known not only for Midas’s more than four decades of empire-building, but also as the city where Alexander the Great, in 333 BCE, cut through the tangled “Gordian Knot” to fulfill a Delphic prophecy about the conquest of Asia. Over time, the city’s location “had been lost to memory,” says the Penn Museum’s Gordion archivist, Gareth Darbyshire. It was (accidentally) re-discovered in 1892, when a team building a branch of a Berlin-Baghdad railway encountered a cluster of man-made mounds in and around Turkey’s Sakarya Valley.

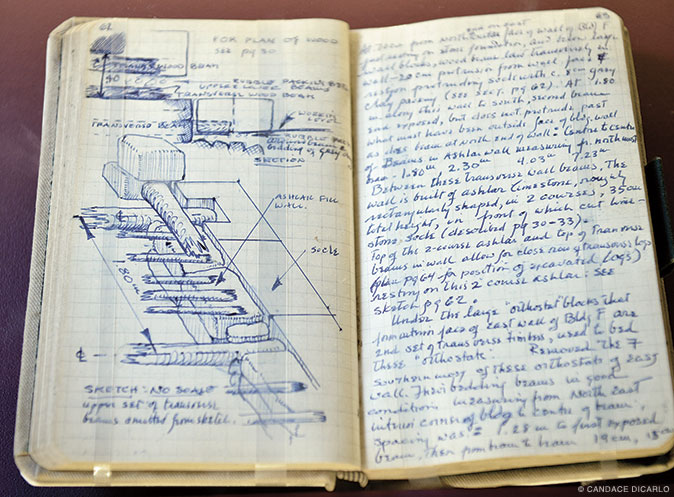

The workers “actually robbed the site to create building materials for construction of the railway,” adds Darbyshire, an archaeologist whose responsibilities include managing and overseeing the digitization of thousands of photographs, journals, drawings, and other materials documenting Gordion. His knowledge of the site is, as one might expect, encyclopedic, and it pours out in dense, rapid-fire paragraphs delivered in a lilting northern English accent.

The pillaging, Darbyshire says, is evident in underpasses, viaducts, and other parts of the railway comprised of “unmistakable polychromatic ashlar blocks characteristic of the Middle Phrygian period,” from 800 to 600 BCE. “The engineers were using Gordion as a quarry,” he says. The materials came from what archaeologists call the Citadel Mound, within which lay traces of Iron Age Phrygia’s impressive administrative and industrial center.

Fortunately, those German railroad engineers decided to contact Alfred Körte, a classical philologist in Berlin. “He was steeped in the ancient written sources, so he must almost immediately have come to Gordion to look,” Darbyshire says. The location, the monumentality of the site, and the presence of “well over 100 elite tumuli,” or burial mounds, helped him identify the place.

In 1900, Körte, whose area of expertise was actually ancient Greek comedies, returned to Turkey with his archaeologist brother, Gustav. They spent a single season digging, establishing the chronology of the Citadel Mound (Gordion was inhabited continuously starting around 2300 BCE) and excavating five tumuli. “They didn’t tackle the biggest one”—Tumulus MM, the Midas Mound—“because they knew it was just too difficult logistically or highly dangerous,” Darbyshire says.

After that, work on the site didn’t resume until after World War II. In the late 1940s, Penn was looking for a major archaeological mission in Turkey, Darbyshire says, and scouted various possibilities. Among them was Sardis, the capital of the Lydian kingdom in what is now western Turkey, whose best known ruler was Croesus (as in “rich as…”). But Gordion was chosen for its historical interest, potential, and accessibility. Since there had been no previous significant excavation of Phrygian sites, “the world of the Phrygians was still a great mystery,” Darbyshire explains. And because Gordion was not “masked by a major modern settlement,” archaeologists would have free rein to dig.

Penn’s first team, led by the archaeologist Rodney Young, excavated for 17 seasons between 1950 and 1973, uncovering much of the eastern half of the Citadel Mound and 30 burial mounds. A second set of digs, directed by Mary Voigt, took place between 1988 and 2006. Summer excavations supervised by Rose began in 2013 and continue in tandem with site conservation and surveying. Only once before the current show, in 1958, has a display of artifacts from Gordion been mounted at Penn, Darbyshire says.

In the early 20th century, artifacts found by archaeologists generally were allocated by partage—a sharing between the sponsoring institution or institutions and the source country. Without partage, museums such as Penn’s could not have accumulated their great collections. But, Rose says, beginning in the 1930s, national cultural-heritage laws began mandating that excavated antiquities remain in their country of origin.

With the Pennsylvania Declaration in April 1970, Penn became the first American museum to promise that it would decline to purchase “any antique that did not have a clear archaeological provenance and an export license from the country of origin,” Rose says. The move was aimed at deterring looting and the resulting destruction of archaeological sites. “We were at the forefront,” Rose says. “UNESCO later formulated its own declaration [in November 1970], but ours came first.”

A museum application to the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism for a loan triggers an investigation, Rose says, “to determine whether the museum in question is an ethical museum and does not purchase antiquities on the art market.” In Penn’s case, the investigation in connection with the Gordion loans raised a question about some Early Bronze Age gold jewelry, from about 2400 BCE, in the university’s collection. The jewelry, which the museum had purchased on the art market in 1966, four years before the Pennsylvania Declaration, resembled Heinrich Schliemann’s so-called Treasure of Priam from Troy, on the western coast of modern Turkey. The issue, according to Rose, was, “Had we acquired something that had been illegally taken from Turkey?”

As Rose tells it, George Bass Gr’64, a curator at the Penn Museum and a pioneer of nautical archaeology, said that the jewelry could have originated in either Greece or Turkey, where Early Bronze Age styles were similar. To help resolve the question, Rose, who had co-directed excavations at Troy for 25 years [“The (Continuing) Tale of Troy,” May|June 2010], brought in his co-director, the German archaeometallurgist Ernst Pernicka, to analyze the gold. One of Pernicka’s colleagues spotted a grain of soil lodged in a gold pendant. On analysis, it proved to be high in arsenic. “And high arsenic levels,” Rose says, “are characteristic of the soil of Troy.”

Given the likelihood that the gold was Trojan, Turkey wanted the jewelry back. In the end, a deal was struck, Rose says: Penn consented to an “indefinite loan” of the jewelry to Turkey, and Turkey agreed to lend Penn 123 artifacts from Gordion and related sites for the Midas exhibition.

A blown-up photograph of Rodney Young introduces the finds from the Midas Mound. He looks far more like an adventurer than an academic—a dashing figure in the Indiana Jones mold, with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. (In fact, during World War II, before the Gordion excavations, he served as an American spy in Greece [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2012].)

Alongside Young’s image, a film clip shows his team constructing a tunnel to penetrate the massive burial mound. About 230 feet long, the tunnel was dug by coal miners from a Black Sea town, Rose says. They worked in shifts around the clock for three weeks so looters could not access the site.

“We’re just very lucky, with 174 feet of earth on top of this wooden tomb chamber, that it didn’t collapse,” as many other such chambers did, Rose says. “Now, this was clearly a tomb built for a king, so they had the best carpenters, the best engineers … They built it to last forever, and it has, in a way—or at least for 2700-plus years.”

The tomb chamber measured about 17 by 20 feet, with a nearly 11-foot-high ceiling; it had a cedar floor, walls of pine, and outer walls of juniper. It had been closed up—with rubble, limestone, dirt, and clay—after the coffin and grave goods were lowered inside. Among those goods, from a funerary feast for more than 100, were three giant cauldrons decorated with small figurines and 167 bronze bowls, ladles, and pitchers. Some of the bowls, Rose says, had wax rectangles added to their sides where mourners had inscribed their names. Also found were 182 bronze fibulae, or garment pins, many likely left by the mourners as gifts; several bronze belts; and 14 wooden serving and dining tables, too fragile to travel to Philadelphia.

“They never bothered to wash the dishes,” Rose says. And that was Penn’s good fortune. While Turkey retained the artifacts, the museum took home traces of the feast and put them into storage. In 1997, Patrick E. McGovern Gr’80 [“Man, the Drinker,” Jan|Feb 2011], now scientific director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project, was able to use such techniques as infrared spectroscopy, liquid and gas chromatography, and mass spectrometry to analyze the residue. This was “the first time really that a whole meal has been reconstructed just from the chemical evidence,” McGovern says. “I was sitting in a laboratory that was two floors below where the bags were of the collected materials, so I always say it was the easiest excavation I was ever on.”

McGovern shows off samples in his office—golden sediment for the beverage, dark brown clumps representing dried-up stew. The stew, he says, was barbecued lamb or goat with lentils, unidentified spices, and “hints of honey and olive oil, which would go well to marinate the meat or to add extra flavor.” The beverage was a mix of grape wine, barley beer, and honey mead, which would have been “on the sweet side.” Dogfish Head, a Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, craft brewery, markets an award-winning re-creation under the rubric “Midas Touch.”

Young thought he had uncovered the tomb of Midas himself. But dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) and radiocarbon dating eventually indicated that its construction was several decades too early. Its size and splendor nevertheless marked it as royal, almost certainly the resting place of Midas’s father.

An interactive display shows visitors what the tomb chamber looked like when it was discovered. Nearby are two of the hefty cauldrons (and a replica of the third), several beautiful bronze vessels and fibulae—and a plaster reconstruction of the dead king’s head.

“The skull had been artificially elongated”—wrapped, when the king was a child, with bandages and boards, as “a marker of royalty,” Rose tells a group of Penn students during an exhibition tour. “You find it in the Old World at Gordion and the New World in Peru, and you’ll see a similar kind of thing used for the aliens in the last Indiana Jones movie.”

When the reconstruction was done, in the 1970s, the king—aged 60 to 65—was still assumed to have been Midas. The Roman writer Strabo claimed that the despairing monarch had committed suicide by drinking bull’s blood after marauders from Southwest Russia invaded his kingdom.

“They made him look like a man who was about to commit suicide and was eyeing a glass of blood on a nearby shelf,” Rose tells the students. “In fact, it’s not Midas, it’s his father; there was no invasion of the marauding tribe from southwest Russia, the so-called Cimmerians, at this point in time; and if you drink bull’s blood, it doesn’t kill you. Those I know who have drunk it say that it’s a kind of energy drink, a kind of Red Bull, coupled with an aphrodisiac. I don’t recommend doing it at home, but it doesn’t kill you—that’s the point.”

Rose also offers an intriguing theory about another Midas myth. Analysis of the royal shroud and other fragments of elite clothing revealed an iron oxide pigment called goethite, after the German poet Goethe, which makes cloth shimmer in the sunlight. “So we think that this is the origin of the golden touch,” says Rose. “Not that people were using a lot of gold, but [that] they were literally wearing it … garments that looked golden as they walked through the streets of the city.”

In fact, just one gold necklace from a Gordion burial is displayed, since little gold was found at the site. But the exhibition glitters with gold from neighboring lands: Persian coins, Lydian jewelry, Scythian shroud decorations. And one glass display-case is filled with silver from a late eighth-century BCE tomb, a woman’s burial in Bayindir, in an area known as Lycia in southwest Turkey. Alongside bowls and fibulae in Phrygian styles and a high-hatted statue of a priest is a silver belt with a filigree buckle and embossed geometric patterns.

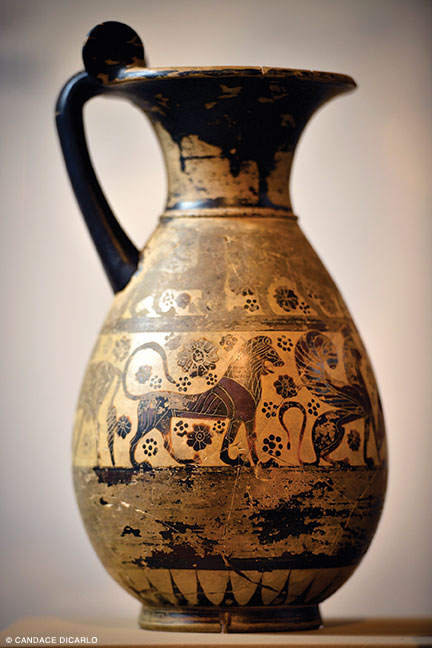

The Phrygians’ predilection for geometric patterning is reflected throughout their material culture: in ceramic drinking vessels, textiles, painted terracotta tiles, and a remarkable ninth-century BCE colored pebble mosaic—the oldest known example of its type. The terracotta and ceramics also sport figural motifs, usually of animals; one tile may portray Theseus confronting the Minotaur in the labyrinth at Crete.

Gordion’s well-fortified citadel is represented by a model depicting its factories for the production of clothing, food, and beer, as well as a palace area. Most of the work was done by female slaves, presumably from conquered kingdoms, Rose says. A rich trove of artifacts was found at the so-called destruction level of the citadel, the result of an accidental fire in about 800 BCE. (Young had a more dramatic, if again mistaken, theory, attributing the scorched-earth cataclysm to an attack by the nomadic Cimmerians a century later.)

The Golden Age of Midas introduces visitors to lingering, and surprising, traces of Phrygia in our own culture. The Phrygian mode of music, as described by Greek and Roman sources, was an antecedent of flamenco and has echoes in the tunes of Metallica and Santana, Rose says. The slouchy, conical Phrygian cap, perhaps confused with a similar cap worn by freed Roman slaves, became associated with liberty in both France and the United States, and still adorns the US Senate seal.

The exhibition also situates Phrygia in historical and geographic context. A timeline, moving backward from the present, is punctuated by Persian and Roman coins and a third century CE papyrus fragment of Homer’s Iliad, which was probably first written down during Midas’s reign. The Phrygians figured in the epic as Trojan allies—not surprising, since Priam’s wife, Hecuba, was Phrygian.

Yet Midas himself was apparently partial to the Greeks. In the fifth century BCE, Herodotus described him as the first foreign king to have made a dedication to the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. The object he dedicated was a wood and ivory throne. On exhibit is an ivory furniture attachment from the late eighth century BCE that depicts a man beside a standing lion. A loan from Greece that was found at Delphi, “it almost certainly would have been part of that throne,” Rose says.

A section of the exhibition uses rarely seen artifacts from Penn’s own collections to introduce Phrygia’s neighbors, allies, and competitors. Highlights include a bronze helmet fragment from Urartu, to the east; gold necklaces and earrings from wealthy Lydia, to the west; Phrygian-influenced ceramics from Greece; intricate ivory carvings from Assyria; and a Persian vessel celebrating “Xerxes the Great King” in four languages.

“Midas was distinctive in that he was reaching out to the powers that lay at both east and west as no other Near Eastern king was doing in those days,” Rose explains. But his reign marked the acme of Phrygian influence: The Lydians would overrun Phrygia in the late seventh century BCE, while the Persians conquered Asia Minor in 546 BCE. A sampling of the arrowheads they used in besieging Gordion is on display.

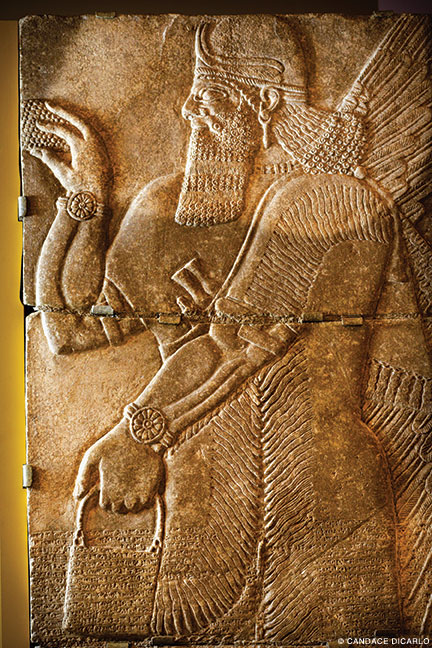

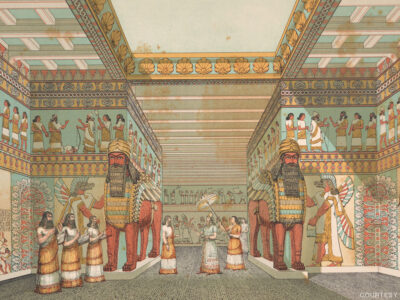

One of the largest objects in the show is what Rose describes as an “elaborate Assyrian relief of a winged man with pine cone and a bucket, symbolic of fertility.” It decorated the palace of Ashurnasirpal II in Nimrud in the ninth century BCE. In today’s war-torn Iraq and Syria, similar treasures are under threat—or already gone. “One of the subtexts of the exhibit,” says Rose, “is that we were highlighting the greatest achievements of the ancient Near East during the early first millennium BC at a time when the tangible evidence of those achievements … was systematically being destroyed by ISIS.”

The excavations at Gordion go on— complemented by conservation efforts and the use of newer technologies such as remote sensing, which can help detect walls and streets below the surface. Rose says his favorite recent discovery is a secondary monumental entrance to the citadel, spanning the ninth to sixth centuries BCE. It ties into a network of roads through the residential district, and represents, he says, “a major advance in understanding the city plan of ancient Gordion.”

Surely, though, the real archaeological prize at Gordion is Midas’s elusive tomb? So far, only 44 of the 124 tumuli at Gordion have been excavated, leaving many discoveries yet to be made.

“Would I like to find it? I would,” says Rose, who has clearly been asked this question many times before. “Do I know where it is? I don’t. Is it something that archaeologists of the future will determine? I suspect it is.

“If I ask myself where would such a tomb be, where would I put it, I would put it next to the tomb of the father, I would make it a dynastic grouping of tombs.

“But the other big tombs in the vicinity of the Midas Mound have been excavated, and Midas isn’t in there because these are tombs that date to the wrong period,” he says. “I’d like to find a tomb with an extensive royal assemblage that I can place in 700 BC, and if that happens, it’s a good chance that it’s Midas’s tomb. But that has not yet happened.”

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, is a contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review and a contributing book critic for the Forward. Her last piece for the Gazette was on Kermit Roosevelt III. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.

Its sad that almost all of the statuettes of women had their faces bashed in by men of the rising male cults of the patriarch between 2nd century bce and the 1st century ce. Including the Cybele (the Mother Goddess).