While no one seems quite able to define what a Young Adult, or YA, novel is, exactly, lots of people—of all ages—are reading them. And quite a few Penn alumni (including the one who asked that question) are writing them.

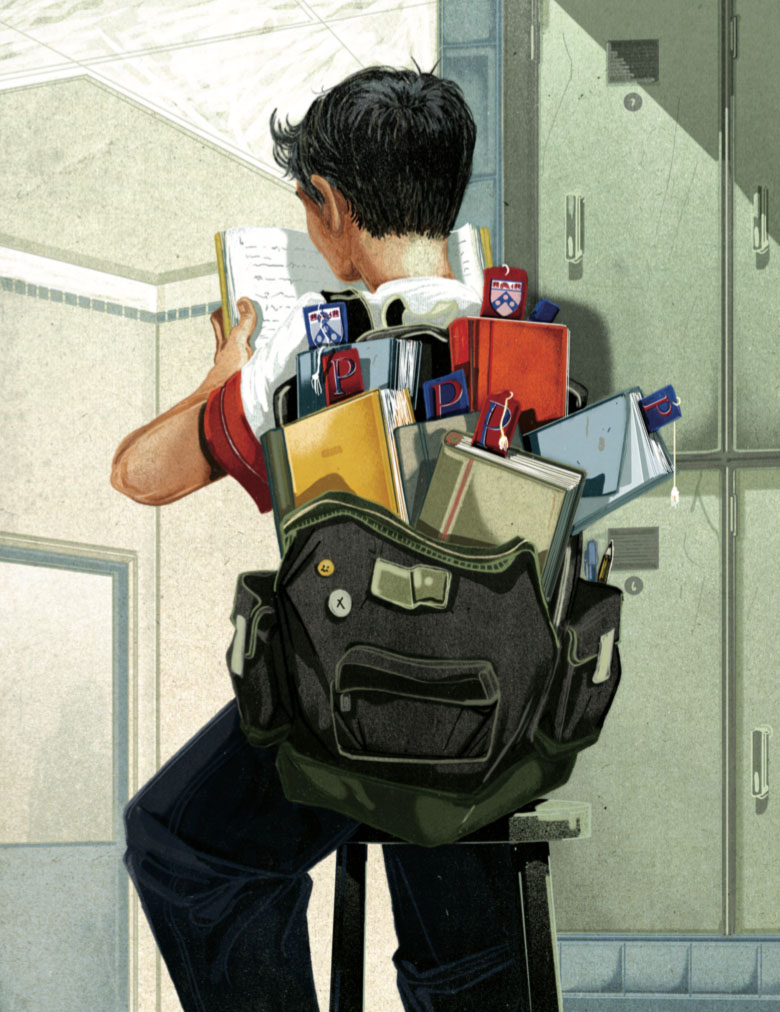

By Molly Petrilla | Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

Jordan Sonnenblick C’91 worried about his eighth-grade student Emily. Though she giggled her way through every class lesson—often to the teacher’s annoyance—when it came to her younger brother’s cancer, she “clammed up and wouldn’t talk about what she was going through,” Sonnenblick says. As an English teacher, he hoped that the right book could help Emily process her pain. With her mother’s blessing, he set out to find it, but soon encountered a hurdle: “I went everywhere and could not find a book about a middle schooler whose younger sibling had cancer.”

Instead of shelving the idea, Sonnenblick spent the next three months writing the novel he’d wanted to buy. He hadn’t written a book before and already had a full-time job, but never mind that. He’d come home after teaching all day, help his wife put their young children to bed, then sit down in his kitchen and pour out the story of Steven, a 13-year-old who thinks mostly about drumming and girls until his younger brother is diagnosed with leukemia.

Some 270 pages and very little sleep later, Sonnenblick had created Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie—a novel for and about young adults. (In the literary world, the term “young adult” is a loose one. Depending on whom you ask, it can refer to books written for kids as young as 8 or 9 and up through 18 and even beyond.)

Sonnenblick soon discovered just how many of those YA readers and their parents had been looking for a book like Drums. He says it’s sold more than 400,000 copies since it was published in 2006 (“it just keeps selling and selling”) and has been added to classroom curricula across the country. It’s won a slew of awards and maintains a near-perfect reader rating on Amazon (4.8 out of 5 stars, with comments such as “a touching book that makes you want to laugh and cry at the same time”).

After publishing Drums, Sonnenblick left teaching to become a full-time author. He’s since released seven young-adult books with male main characters—most recently, Curveball this past March—and has another novel due out next year. “I don’t know what I did right,” he says, “but I’m thrilled, because what I write isn’t about vampires. It’s not about zombies. It’s not about werewolves and it’s not about wizards. It’s not dystopian. I write really realistic fiction, which is a fantastically unfashionable neighborhood of the YA genre right now. I don’t try to analyze the market trends because I’m thrilled that I have my own little niche and it’s working.”

It turns out he’s not the only one. At least a dozen alumni, all of whom graduated from Penn within the last three decades, have revisited their painful, funny, embarrassing adolescent years to create young-adult novels. As Sonnenblick puts it, YA is “a hot field, and Penn is hotly represented in it.” And while their subgenres cover a broad swath of literary ground, there isn’t a vampire, wizard, or dystopian future in sight.

The funny thing about the genre these Penn-educated YA novelists have chosen is that it didn’t yet exist when they were young adults themselves—at least not in a form easily recognizable to anyone who passed their adolescence with venerable book series like the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew and such “children’s classics” as Little Women, The Swiss Family Robinson, and Treasure Island. There were bits of a teen-focused canon out there—The Outsiders, A Wrinkle in Time, several Judy Blume works—but certainly not enough to warrant its own section of the bookstore.

“When I was in high school, I think there was one shelf in the children’s section for teenagers,” YA author Susane Colasanti C’95 says. “In school, the books we read were presumably Young Adult, but really they were classic literature. I love that teens have a really good selection now of novels written for them, and I love that there are so many subgenres within YA that they can connect to.”

There’s been some disagreement over when and how the genre became what it is today, but lots of fingers point to a certain lightning-scarred wizard who invaded the US in 1998.

“It had to have started with Harry Potter, as so many things did,” Melissa Jensen C’89 G’93 says. “That’s when I started noticing and paying attention to what was on the bookshelves for adolescents and teenagers.” Jensen speaks from a unique vantage point. She’s written two young-adult books and has also taught a class at Penn on “writing for t(w)eens” for several semesters. “There absolutely was a stigma attached to people who were trying to write young-adult books before Harry Potter,” she adds. “Had Stephenie Meyer written Twilight 20 years ago, she would have been absolutely stigmatized as writing puff about neck biters. Instead, she is now iconic and her books are read by millions of people.”

But what makes them young-adult books, exactly? There were plenty of not-so-young adults reading the Harry Potter books and the Twilight series—and likely some not-yet-young adults reading them, too. “Everyone has a definition of YA that ultimately, at core, is one thing,” says Beth Kephart C’82 [“More Light,” Nov|Dec 2010], a YA author who teaches nonfiction writing at Penn and also writes occasionally for the Gazette. “It’s a story told through the eyes of a teen and limited to what teens understand at that point in their lives. Within that, you can do—and should do—almost anything.”

There are also basic differences in telling a story to teens. “We can’t wait for some of the tricks of adult storytelling to work,” Kephart says. “We have to enter the story right away. We have to move it crisply.”

“Adult novels can be longer and more meandering,” Sonnenblick adds. “When you read a young-adult novel, it’s so much more tightly crafted and edited because editors are so aware of teenagers’ attention spans. You wind up with a much more tightly plotted novel. I’m very aware of that when I read adult novels now. A lot of times they seem very meandering to me.”

People typically associate YA writing with the crazes it has unleashed. First wizards and magic invaded pop culture due to Harry Potter. Then vampires grabbed us by the neck after Twilight. And most recently, The Hunger Games trilogy turned dystopian landscapes into the newest YA trend. To Kephart, these fads can overshadow the rest of the storytelling that young-adult writing has to offer.

“I do mind that so much of the conversation is about Twilight and dystopia and all of that,” she says. “There are a lot of us working in the trenches here who are doing everything we can with language and who are honoring the intelligence of our readers and who believe that we can do meaningful work without going to a dystopian landscape. I’m not in any way dismissing the form; I just wish there was more conversation about the real art that’s going on out here in YA.”

During the most tumultuous years of her life, Susane Colasanti slept with a copy of The Outsiders under her pillow. She now sums up those middle- and high-school years as “horrible.” She woke up dreading school every morning, bracing herself for the inevitable teasing from classmates and lunches eaten alone in the bathroom. “I’m from a family without a lot of money,” she says. “I went to a high school with a lot of rich kids, and I just didn’t fit in. If you show up in a $2.99 K-mart T-shirt and everyone else is wearing $100 Esprit sweaters, you stand out.”

As if that weren’t enough, “I was a huge science nerd and nerdy kids always get picked on,” she says. “And I was just a very awkward teenager. I had bad skin, my hair was really short—I just didn’t fit in physically with the girls.”

In S.E. Hinton’s novel, Colasanti discovered kindred outcasts who struggled with economic disparity and the same feeling of exclusion. “I clung to that book like a life raft,” she says. “When I say The Outsiders saved me, I’m not kidding. It kept me sane. It kept me going every day.”

You’d think Colasanti would desperately avoid looking back on those painful teenage years. Quite the opposite. The teacher-turned-full-time-novelist spends every day immersed in young adulthood, writing about teen girls who grapple with “soul mates and true love and romance.”

Though she’s woven many of her own experiences into her six novels, her latest book is especially personal. Published this past May, Keep Holding On follows Noelle, a girl from a poor family who goes to high school in a rich town. “It focuses on the consequences of bullying,” Colasanti says. “It’s a book that I just felt really strongly about writing.”

Just as there is no standard young-adult book, there is also no standard young-adult-author; yet in speaking to Colasanti and other Penn alumni YA writers, there are certain shared teenage experiences that emerge: feeling shy or awkward or uncomfortable around peers; a love of books and reading; questions about what adult life will entail—and a willingness to dive back into all the dramatics and broken hearts and struggles of those chaotic younger years.

Like Colasanti, Sonnenblick describes a difficult young adulthood. “I was a miserable teenager,” he says. “I was hyperactive and unhappy and angst-ridden, and I got in trouble all the time in school. I was an unchallenged smart kid with a fast mouth.”

So why revisit that time? “I’m fascinated by that period in kids’ lives,” he says. “It’s such a tumultuous time that you never run out of stuff. If you picked any other six years of a person’s life—if every book I’d written had been about characters between the ages of 40 and 45, for example—those would be such boring books. But there’s such an amazingly fertile period of growth and development and change and topsy-turvy-ness [during adolescence] that there’s endless fascination there.”

Colasanti has another explanation for her chosen career: “People who go through traumatic experiences tend to get really attached to that time and make it their purpose to reach out and help other people survive the same thing. I love writing about [young adulthood] now because it makes everything I went through worth it. Now I can reach out to teens and hopefully help them feel less alone. I’m all about turning negative experiences around into positive ones.”

Lisa Ann Sandell C’99 often writes about the challenges of teenage girlhood. She remembers her teen self as “painfully shy” and “desperate to fit in,” and has drawn on both feelings in her three free-verse YA novels. “Everything felt heightened during my adolescence,” she says, “so those feelings of alienation, confusion, and great, glowing hope have stayed with me, often suffusing my writing.”

In her second book, Sandell—who works full-time as a YA book editor at Scholastic—found inspiration in her academic endeavors in addition to her adolescent angst. Almost a full decade after studying medieval literature at Penn and crafting a senior thesis on the legendary King Arthur and Sir Lancelot, Sandell wrote Song of the Sparrow. Set in the year 490, the novel follows a 16-year-old Elaine of Ascolat (the Lady of Shalott) as she struggles with unrequited love for handsome Lancelot and envy of the beautiful Gwynivere.

Sandell, Colasanti, and Melissa Jensen—author of Falling in Love with English Boys and The Fine Art of Truth or Dare—have all found success in the YA-for-girls market. Books written specifically for young boys had become relatively rare as the YA genre burgeoned and also broke down increasingly along gender lines—with books targeted to girls generally leading in sales. In a New York Times article lamenting this trend, journalist and YA novelist Robert Lipsyte cited a publishing executive who said at a 2007 American Library Association conference that “at least three-quarters of her target audience were girls, and they wanted to read about mean girls, gossip girls, frenemies and vampires.” He called for richer reading options for boys than the typical “supernatural space-and-sword epics that read like video game manuals and sports novels with preachy moral messages.”

Penn YA novelists are doing their part.

After writing books and a weekly e-newsletter about his own life, comedian Aaron Karo W’01 recently decided to give fiction a try. He came up with the title first—Lexapros and Cons—and then his main character, a teenager named Chuck Taylor who has obsessive-compulsive disorder. “People got very excited about this idea in the YA world because there aren’t a lot of guy-focused books,” Karo says. “I didn’t even know what young-adult [fiction] was. My agent said, ‘This would make a great YA book,’ and I said, ‘What’s ‘ya’?”

It turned out Karo had stumbled into a YA subgenre still in its infancy—or perhaps its young adulthood. When Stuart Gibbs C’91, a TV and film writer, had approached publishers in the early 2000s about writing books for boys, he’d heard a resounding no. “They said boys go straight from picture books to reading their dads’ stuff,” Gibbs says. “There didn’t seem to be a market for it. And then about five years ago, suddenly there was.”

In 2010, Simon & Schuster published Gibbs’ first book, Belly Up. Lightly inspired by Gibbs’ experience working at the Philadelphia Zoo while a student at Penn, Belly Up takes place in the fictional FunJungle—“the newest, most family-friendly theme park in the world.” When the park’s superstar hippo turns up dead, 12-year-old Teddy Roosevelt Fitzroy suspects foul play and sets out to uncover the truth.

Gibbs has continued writing adventure and mystery stories for the youngest young-adult readers. Spy School came out in March, and he is now in the midst of a Three Musketeers trilogy called The Last Musketeer. While his books feature male protagonists and storylines that will appeal to boys, Gibbs says he hopes girls and parents enjoy them, too.

Sonnenblick, who has been writing books with boys as main characters for longer than most, says he created his most recent novel, Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip, for his teenaged baseball-playing son. In the book, Peter Friedman—named, coincidentally, after one of Sonnenblick’s Penn friends—suffers an injury that ends his high-school pitching career. At the same time, his grandfather is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Sonnenblick says he doesn’t write specifically for boys, noting that they make up only about half his readership. Still, the fact that he’s writing male main characters in award-winning YA books sets him apart. As one reader noted in a Goodreads review of Curveball, “Sonnenblick has quickly become one of my favorite YA writers for guys. He does an amazing job of mixing humor, realistic characters, and honest presentations of tough issues that kids face. This most recent novel doesn’t disappoint. It is a page turner and Peter, AJ, and Angelika are really strong characters that you can imagine walking the hallways in any high school.”

Once a misfit teen forced to eat lunch alone in the school bathroom, Susane Colasanti now has a legion of devotees. After watching an interview with her on YouTube, one viewer wrote: “Colasanti is the most Awesome person ever!!!!!!!!!!!” Another added: “Susane! You’re so down to earth and cool.” She has nearly 3,000 fans on Facebook and answers almost every comment they write on her page. She recently agreed when a fan called one of her male characters “a real jerk” and told an effusive teen admirer, “Thanks for the warm fuzzy :).”

Though Colasanti could only imagine having such candid, direct interactions with S.E. Hinton and other beloved writers during her own teenage years, such back-and-forth is commonplace—expected, even—between today’s young-adult readers and authors.

When Stuart Gibbs began writing books a few years ago, his publisher made it clear that a blog, Facebook page, and email address were “de rigueur,” Gibbs says. “I actually think that’s one of the things that might be spearheading this interest in young-adult fiction,” he adds. “Now with the Internet, kids can be very active in their relationships with authors. They can write to me. I Skype with schools. They have all these tools now that we didn’t have when we were kids.”

Sandell says that enthusiastic readers make writing for young adults especially rewarding. “They are incredibly responsive [and] eager to be in touch with the authors whose books they love,” she says. “I’ve been lucky to have repeat correspondence. Some girls have read one of my books and then written to me again after they’ve read others. It’s always gratifying to hear from someone who’s taken the time to reach out not just once, but twice.”

Both Colasanti and Sandell have heard from a number of girls who say they previously hated to read. “It really pains me to hear from readers who tell me that my book was the first one they’ve ever read cover to cover,” Colasanti says. “I hear that from a lot of readers, actually. On one hand, I’m glad that they’re finally getting into reading, but on the other hand, I’m really sad that they haven’t loved it up until now.”

Admiring readers come in all ages. The story is too personal to name names, but Sonnenblick talks about a famous fan that Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pieearned him. The drummer from a well-known rock band (again, no names offered) emailed Sonnenblick after picking up a copy of Drums at Barnes & Noble and reading it while on tour. He offered the author two backstage passes to an upcoming concert and invited him to come chat afterward. “It turned out that he’d had a sister who had cancer when he was a kid,” Sonnenblick says. “It wasn’t the drumming that had made him contact me and send me backstage passes to his concert, it was that he was a cancer sibling.”

The anonymous rock drummer isn’t the only grownup reading—and relating to—young-adult books. Penn’s alumni-authors have all heard from adult readers who connected with their books or just plain enjoyed reading them. It backs up what several of the authors claim: They aren’t writing books specifically for teens, but rather for readers.

“I don’t think I write for young adults,” Sonnenblick says. “I think I write about young adults. I think the idea of writing for young adults sounds like you’re writing these pre-canned books, like you’re writing down to kids, and I don’t do that.”

Beth Kephart, the Penn writing teacher and author, is careful to make the same distinction. “When I began writing YA, I said I would never write down—I would never simplify—because I have such enormous faith in the intelligence of young people,” she says.

Still, plenty of adults continue to dismiss the YA genre. “I’ll go to author events and people will say, ‘What’s your most recent book?’ and I’ll say, ‘It’s a young-adult novel that takes place in Spain,’ and they’ll say, ‘Oh. Tell me when you write something for adults,’” Kephart says.

Even her friends are guilty of such comments. “I would like to be able to walk into the next cocktail party and not have someone go—and someone did say this to me, and he was joking, but he meant it—‘She only writes YA. You don’t want to talk to her. Talk to someone intelligent.’ He was joking, but you get that as a young-adult author.”

Kephart may not have to smile through the “jokes” for much longer, though—at least by her own estimation. “I give it three to four more years before we stop seeing all the stories about YA,” she says. “I think that there are so many books in YA that are also being read by adults that maybe, hopefully, we’ll stop talking about it as a category and just be looking at books as books.

“I’m certainly not suggesting that we’re going to take away the YA label,” she adds. “What I am suggesting is that we’ll stop musing about it. We’ll stop wondering, ‘Why this category?’ I think it’s just going to be accepted and the books are going to be honored and read by broader audiences more and more.”

Molly Petrilla C’06 writes frequently for the Gazette and oversees the magazine’s arts & culture blog.