Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library has a message for students, alumni, and book lovers everywhere. Online or on campus, come up and see us sometime!

By JoAnn Greco | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar | Rare Books Abound in Philadelphia

On the first crisp evening of the Fall semester, some 50 students stuffed themselves into the baronial Henry Charles Lea Library. The room, tucked away on the sixth floor of Van Pelt Library, was overheated, and shrugged-off backpacks and jackets lay in heaps on the oriental rugs. Their owners had come to this session of the weekly seminar in the History of Material Texts to take an intimate look at a very small (five inches by three-and-a-half inches), very old (11th-century) parchment book containing the Book of Psalms. Known as a psalter, the volume is one of the stars of the Lawrence J. Schoenberg & Barbara Brizdle Manuscript Initiative, an effort to help Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML) build its collection of pre-1600 works. That initiative has seen the acquisition of 10 codices—handwritten, bound books (as opposed to scrolls)—and half a dozen fragments in the last two years.

While some items are bought at auction, most of the materials included in the RBML—which was formally created in the 1940s to assemble some 200 years of collecting under one roof and one acquisition program—come via donations. Not every one of the 300,000 or so items that make up the collection is, technically speaking, rare, or even all that old. It includes the entire archives of Philadelphia-based Curtis Publishing, the complete papers of local author and Penn professor Chaim Potok, and dozens of other special assemblages covering everything from the history of chemistry to Shakespeare through the ages.

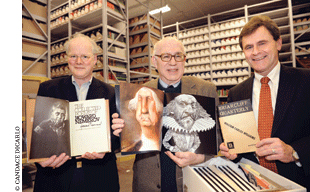

In December, the RBML received the contents of the legendary Gotham Book Mart, a New York institution frequented by generations of book lovers and literary folk, which closed its doors in 2007. In all, about 200,000 items—advance reading copies, small press publications, and volumes of modern and contemporary literature, among other materials—were given to the University by an anonymous donor; they had earlier been bought for $400,000 at auction by the store’s landlords.

Even before the Gotham donation, the RBML had been a decidedly crammed operation. Uncatalogued materials sit in piles in the library’s offices, while tomes that have already received their color-coded slipcases—custom-sized boxes covered in Japanese silk and assembled by a Vermont-based artisan—await shelving. “The need for more space is the primary driver behind what’s turned out to be a five-year call for renovating and expanding our space,” says David McKnight, who directs the RBML.

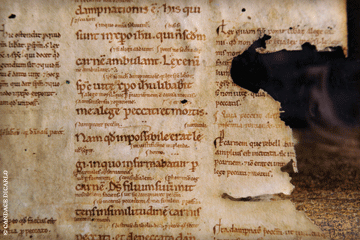

ordinaria fragment (France, between 1135 and 1150).

Improving the facilities and enhancing the accessibility of the RBML’s materials is a major focus of the library’s goal within the University’s ongoing Making History campaign. Plans call for increased storage, as well state-of-the-art climate control, dedicated space for the facility’s part-time conservationist, and—perhaps most important—additional classrooms, so that more people can get in touch with more materials, more often. (For information, visit www.makinghistory.upenn.edu/libraries.)

“We’re really interested in acquiring items that are likely to be useful to the faculty and students,” says Amey Hutchins, assistant curator of manuscripts. “When we started the medieval initiative, we interviewed a lot of faculty to determine their interests. We feel the greater the potential for constant use, the more valuable the book will be to our collection.”

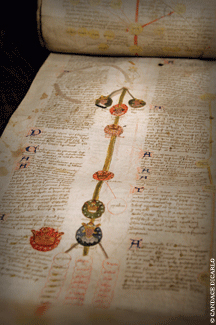

She hands over a small red leather box that opens to unveil not an emerald necklace or a pearl bracelet, but a jewel of another sort: a 15th-century Italian vellum choir book that the library bought at a Sotheby’s auction in London. “Go ahead, take it out,” Hutchins exhorts. “We have a no-gloves policy here.” Bare-hand encounters strengthen the tactile connection between book and reader, curators believe, while reminding us of the material’s fragility and our responsibility to take care.

“We liked this book because we thought it’d be great for a particular faculty member in the music department who’s always looking for primary sources to study music theory,” Hutchins continues. “This book was used as a tool to teach monks what’s known as ‘sight-singing,’ and here”—she turns to the back of the volume—“there’s a drawing of a palm where the joints of the hand are marked with musical syllables. It was a popular memory aid of the time.”

In the case of the tiny 11th-century psalter—also known as Codex 1058—an entire class has been built around examining its secrets: Glossed Books and Medieval Learning, co-taught by E. Ann Matter, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Religious Studies and associate dean for Arts and Letters, and Robert A. Maxwell, associate professor of medieval art and architecture.

At the seminar in the Lea Library, Matter was giving those present a kind of preview of the class and how it would make use of the latest digital technology to study this centuries-old text.

As she spoke about the monastic practice of “glossing,” or translating biblical text and adding marginal commentary, an image appeared on a screen set up in the library: a page crowded with flowing lines of large text on the right-hand two-thirds, and much smaller scribblings on the left third, in between lines, and along the top margin. “By the 12th century, there’s a standard for most parts of the Bible. You can read the same commentary in all manuscripts,” Matter said by way of introducing what she calls “our manuscript.”

“But this is a very interesting example because it’s so small, and since it’s so small, it’s been well-thumbed on the corners, and the glosses are very hard to read,” she continued. Smudges and stains obscure the faded commentary, which is lighter and denser than the biblical text it expounds upon.

The book’s age and condition ensured that the work of the class would be slow-moving, and its rewards incremental. For some scholars, though, such wear only adds to the text’s richness. “The more hand grease, the better,” laughs Peter Stallybrass, the Annenberg Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English and of Comparative Literature and Literary Theory, who directs the History of Material Texts seminar [“Making the Most of the Material Past,” Mar|Apr 2002]. Candle burns? Great! Wax drips, wormholes—bring them on, he says.

“To me, it’s not terribly interesting if something hasn’t been extensively opened and touched,” Stallybrass observes. “It says the book has had absolutely no impact.” Even ink colors—or lack of them—can mean something, Stallybrass believes. When Matter notes that Codex 1058 isn’t lavishly illustrated and that even its rubrication—the medieval practice of adding red to certain bits of text—disappears by the tenth folio, Stallybrass interjects excitedly: “Perhaps that’s something worth examining!”

Maybe so, but because this psalter was glossed decades before a standard text was developed, religious scholars have different questions. “Look at this closeup,” Matter directs the assemblage. “See how the text continues above the line, rather than continuing onto a second line, when the scribe runs out of room? That’s an Irish scribal practice—and that’s one of the questions about this French book. Does it have some sort of Irish cast to it? We know a lot about the different glossing traditions,” she adds, “and this manuscript doesn’t conform with any from the same period.”

As the images on the screen zoom and then zoom again, and Stallybrass and the others present lean forward, Matter emphasizes the contribution of the technical experts who have made such close inspection possible. “The psalter is still a work in progress,” she says, “and it’s a constant collaboration between the folks at SCETI and our class. Every week, we see something we want them to change or to add.”

Down two flights in the Van Pelt building, the small staff of SCETI—the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image—is tooling away at just such wizardry. In a glass-enclosed office, an intern sits in a darkened corner before one of three scanning stations, patiently wading through Box 14 of the 41 cartons constituting the Keffer Collection of Sheet Music, some 2,500 scores—about half of them published in Philadelphia—of 19th-century American popular music. Using a high-end Hasselblad lens and a Phase One P45 39-megapixel digital camera mounted on a copy stand, he photographs each piece. About five seconds later, the RAW image appears on his Mac, opening in an editing program called Capture One Pro. Typically, this digital image will record at 600 dpi, at 100 percent of its size and with as little tech fiddling as possible.

“We may adjust white balance, but that’s about it,” says Chris Lippa, scanning supervisor for SCETI. “We try not to have a need to correct—we’re trying to keep as true to the page as we can get.” Digitizing—the proper term in this case, since scanned implies the use of a flatbed scanner, a machine that records images of a lower quality—serves two purposes, Lippa points out. “There’s the archival aspect, of course, where the material is forever preserved as is, and protected from further wear and tear,” he says. “And there’s the notion of increasing the materials’ accessibility by placing it online or, in some cases, on a CD. Archiving is necessary and practical, but for me, what’s really cool is looking through this stuff and knowing that it’s soon going to be out there for an unknown and, potentially huge, population.”

Lately, the pace of digitizing has been stepped up—with SCETI now working at a rate of 3,000 captures a month, says Lippa. Recent projects range all over the geographic and chronologic maps, from an Abraham Lincoln letter to an 11th-century Koran to “Fragments From France,” a portfolio of comics written and drawn by British World War I captain Bruce Bairnsfather.

Once Lippa and his team digitize a manuscript, SCETI web developer Dennis Mullen usually steps in, charged with moving the material onto the web. “This whole project got under way when [library overseer] Larry Schoenberg [C’53 WG’56] began exploring ways to share his private collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts,” Mullen recalls, “but it’s just taken off since then.”

As the center has expanded its capabilities in the last decade, it has also had to contend with new challenges. For example, because the Glossed Psalter requires such close study, they created an online magnification tool. With such proficiency has come increased demand. “We’re going to have to look at some sort of standardized procedures to decide what gets digitized,” Mullen observes. “What started as a Rare Books initiative now has a life of its own.”

Although SCETI has digitized everything from the University’s art collection to a project called Philadelphia Neighborhoods that incorporates various city planning documents, it’s likely to continue focusing on rare books and manuscripts—and not necessarily only those held by Penn.

The Penn/Cambridge Genizah Fragment Project, for example, has digitized nearly 500 fragments—dating from the ninth to 15th centuries—of the Cairo Genizah (a repository for old, used and damaged books, Torah scrolls, and other documents containing the name of God, whose destruction Jewish tradition proscribes). An attempt to reunite these pieces, the project includes fragments from the collections of Penn, Cambridge University, and the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. “Right now, this is our biggest collaborative effort,” Mullen says, “but there’s no doubt that this will be the wave of the future. The online collection winds up being bigger than its parts, and everyone benefits.”

It also keeps these institutions on the cutting edge of a world increasingly turning to technology to preserve and make accessible everything from texts of unparalleled historic significance to quotidian titles from modern-day backlists. “This is the name of the game,” points out H. Carton Rogers, vice provost and director of libraries. “The Web is a great opportunity for us—but it’s also the curse of the times. If something’s not up there when you do a Google search, it might as well not exist. How we identify and take advantage of these opportunities is what’s going to move us forward.”

Just in the last year, three headline-grabbing stories spotlighted this merger of PCs and parchment: Israeli technicians began digitizing the Dead Sea Scrolls, uncovering previously illegible bits in the process; an international team completed a 10-year effort to study, and digitize, a palimpsest of a 13th-century Byzantine prayer book crafted from folios originally containing texts and formulas written by Archimedes; and Google announced plans to scan millions of out-of-print books and make them available for reading and purchase online.

“For any number of reasons, digitizing helps the world’s libraries do their jobs better,” Rogers sums up. “It’s a great way to empower scholars and readers from around the world to gain access to whatever they desire. And what we’ve found is, the more you digitize, the more the original gets used. It’s not as if a digital version supplants the original. Instead, it whets the appetite to see the original, if not now, then one day.”

In fact, this renewed digitization effort is just one way of realizing the RBML’s goal to get users into contact with the material. “So many alumni tell me that they never went to the sixth floor, that they didn’t know they were welcome up there. I sure want to change that,” says Rogers. ”I make a point of telling incoming freshmen at orientation that if their coursework doesn’t take them there, then they should come in on their own and sit down and have a look at a Shakespeare First Folio. To feel it and smell it is an extraordinary experience, and one that you don’t get all that often in life.”

Seminars like the History of Material Texts, lectures related to aspects of the collections, and exhibits like the current “Life in Boxes: Comic Art & Artifacts” (through March 22), as well as the dozens of courses that focus on specific manuscripts, together bring some 3,000 visitors a year in contact with the holdings. “This stuff, which can be so harmed by water and by fire, also is incredibly durable. It lasts, that’s what’s so great,” RBML director McKnight enthuses. “Vellum and parchment can survive for centuries. It can still be crisp, and brilliant, and colorful.”

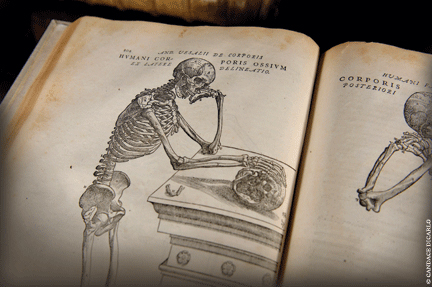

Any book lover who indulges in a short tour through the sixth floor will feel similarly awed. To wander the stacks and small, disparate collections is to be lost in an enchanted paper forest, complete with the smell of beaten leather, the snap of crinkled pages, and the eye candy of etchings and illuminations, of sepia photos and curvy F-clefs. There’s the Philadelphia-related arcana that transcends local interest: from the scores once owned and used by Eugene Ormandy to the 10,000-volume library of recipe books and manuscripts related to cookery, donated by Fritz Blank, chef-owner of the shuttered Center City restaurant Deux Cheminées. There’s the scholarly: from the leather-bound tomes on the Spanish Inquisition and torture that make up the Lea Library to the explorations of the Bard in the Furness Shakespeare Library, donated to the University in 1932 and added to ever since. The Furness collection is so complete that it even includes The Idiot’s Guide to Shakespeare. There’s the specialized: from the still-boxed 23,000 comic books and graphic novels—from D.C. to Disney—donated by Steven Rothman C’75 to the Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection, named for the longtime professor of chemistry and Penn provost from 1910 to 1920. That collection relates the history of chemistry through works on alchemy and pyrotechnics, biographies and vintage photos of eminent chemists, and rare volumes.

The fact that photographs and scores make it into the Library—as well as circus posters and Yiddish record albums—is a testimony to its generous boundaries. “Not everything in here is a book, and not everything is solid gold, not by a long shot,” says John Pollack, public services specialist for RBML, as he leads a tour through the stacks. “Steve’s collection of comic books is not especially valuable, for example. They’re from the 1960s to 1990s, not the ’30s or ’40s.”

So why give them a home? “The sheer volume is impressive, and they’re of great interest visually,” Pollack begins. “But, also, they play an important role in popular American culture, and they, like all comics, address the concerns of their time. So you can examine gender roles. Or violence. I can think of half a dozen potential exhibit topics.” Strolling the aisles, Pollack pauses at another section, running his fingers along one of the shelves. “Now this is clearly a rare book,” he says, proffering an oversized leather-bound edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost from 1688. “You might think this would appeal to a totally different audience than those who are caught up in the world of the Justice League,” he says. “But put this next to a comic book, and they both become more meaningful. Comparing the engravings in this four-century-old book with the artwork in a 1988 graphic novel is fascinating.”

It’s no surprise that the staff here love books. But they’re also forceful advocates for marketing and sharing the wealth of material. “I regularly write emails to the faculty saying, ‘I know you’re teaching such and such, and would you like to come in and take a look at such and such?’” says Pollack.

“It’s just part of our everyday fight against the perception that we’re a closed-door operation.” Any visitor who’s held a 15th-century, three-inches-by-two-inches bit of parchment in his or her hands, or watched as an 11th-century book of psalms came to life on a computer screen, might say that the fight’s being won.

Rare Books Abound in Philadelphia

Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library may be the “elephant in the room,” as Director of Libraries Carton Rogers puts it, but the fact that 32 other rare book and manuscript libraries have joined with it to form the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collection Libraries (www.pacscl.org) showcases the abundance of library resources in the University’s back yard. Members include several other major regional universities, as well as local treasures like the storied Rosenbach Museum & Library, with its Sendak sketches and Moore meters, but also lesser-known libraries such as the Presbyterian Historical Society and the German Society of Pennsylvania.

The founding organizations first came together in 1985, as an informal cooperative with a shared agenda ranging from access to public programs and development. Since then, PACSCL has doubled in size and pursued projects ranging from online public-access catalogs to workshops and seminars for librarians and archivists on a variety of cataloging, collaborating, and acquisition/deaccession issues.

As it looks to the future, PACSCL has identified some key priorities for the next few years, including—naturally—networked cataloging and digitization programs.

—J.G.