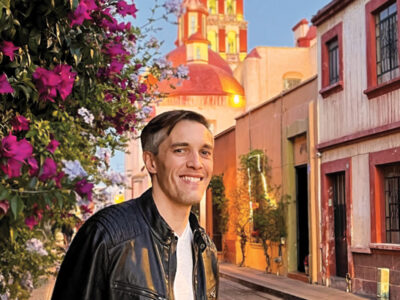

Class of ’82 | Steve Kashkett C’82 may have first heard the siren song of foreign travel in some international-relations classes at Penn, but it wasn’t until he left—temporarily—that his calling became clear.

“I realized that it’s pretty hard to understand what’s really going on in foreign countries while sitting in a study carrel in Van Pelt,” he says, “so I took a few years’ leave of absence to travel with a backpack in the developing world.”

Now, having served as a career diplomat for the past 25 years, Kashkett’s resume includes such diverse—and dangerous—overseas postings as the political officer at the US embassy in Beirut, during a time (early-mid 1980s) when that city was arguably the most dangerous place on earth, and as the political officer in Port-au-Prince during three years that saw four “unscheduled” changes of government. (Balancing that was a stint as US consul general in eastern Canada, based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, “the most peaceful place in the world.”)

Nor could his domestic assignments at the State Department be considered dull. He served as a country officer (aka desk officer) in charge of Northern Ireland in the European bureau, when negotiations for the historic Good Friday Agreement were under way; as senior advisor to the coordinator for counterterrorism during the three years leading up to 9/11; and as head of the American Foreign Service Association, the labor union for US diplomats at the State Department.

But since August 2009, he has been handed one of his most challenging assignments so far: consul general in Tijuana. Though that and other US consulates on the Mexican border have become some of the most dangerous diplomatic places on the planet, he notes, “they get less attention than hot spots in the Middle East or South Asia, because terrorism by narco-cartels is less in the media’s eye than political/sectarian terrorism.”

The Tijuana consulate employs 50 Americans from the State Department and other US agencies, as well as 100 Mexican employees, all “courageously working to help Mexico fight organized crime, drug smuggling, and trafficking in persons,” he says. They’re also helping to modernize the congested San Ysidro border crossing while processing hundreds of thousands of Mexican visa applications each year and assisting Americans who are “victims of robbery/assault/kidnapping, who get arrested, who are serving sentences in Mexican prisons, who lose their passports, and who need other US government services.” Last but certainly not least, he and his staff act as “the eyes and ears of the US government in this volatile and critically important part of Mexico.”

Kashkett recently spoke by email with Gazette senior editor Samuel Hughes about the life and times of a foreign diplomat.

What are some of the most important attributes of a good Foreign Service officer?

Well, the obvious one is just being the kind of person who enjoys the experience of living in different foreign countries—you’d be surprised how many people I’ve come across in the Foreign Service who really don’t like that! But beyond that, the most important character trait is adaptability. Every two or three years, you need to be able to move to a different embassy or consulate in a different country with a different culture, and to adapt to a whole new group of colleagues and friends. You’ve got to be able to wing it in a new language and have an indestructible stomach that can do battle with amoebic dysentery on a regular basis.

What were the most dangerous/sobering/exciting experiences for you in your pre-Mexican career?

I’ve been assigned in the right place at the right time—or maybe it’s the wrong place at the wrong time—pretty often, so I’ve got more stories than most. Some of the memorable ones were: sitting with some embassy colleagues in a restaurant in east Beirut during the civil war when it took a direct rocket hit, and all that the Lebanese restaurant owner was worried about was that the meal for this rare group of American customers had been ruined!

In Haiti, I got to go with our ambassador at 3:00 one morning to the home of one of the country’s last military rulers (who was in his pajamas at the time) to tell him—diplomatically—that it was time for him to leave and that a US military transport [plane] was on the way to pick him up. Jerusalem was a source of endless stories, like being in the room while a steady stream of US envoys tried desperately to make Israeli and Palestinian negotiators play nice, and being confronted constantly in the West Bank by rock-throwing Palestinians and gun-toting Jewish settlers, usually from places like Brooklyn, New York, and Akron, Ohio.

What was involved in being a “country officer” in Washington?

Country officer is the State Department term for the working-level FSO in Washington who’s responsible for handling whatever comes up in the day-to-day bilateral relationship between the US and that foreign country. So when I was country officer for Ireland, I had to draft all the briefing memos on the Northern Ireland peace process and handle all the official visitors from Ireland. The country officer also deals with our embassy in the country on a daily basis—which in my case, as Ireland desk officer in the mid-1990s, meant dealing with the constant, off-the-wall demands from one of our, shall we say, more “challenging” political-appointee ambassadors, Jean Kennedy Smith, sister of JFK.

How bad is it in Mexico, especially the border towns, these days? Are the news media painting an overly negative picture or should they be reporting more on the situation?

Well, the truth is that violence by organized-crime cartels fluctuates wildly, depending on the interplay between the cartels and the Mexican security forces, and the situation is completely different in each part of the US-Mexico border. Here in Tijuana, we had a fairly rocky period last winter when the cartels were going after each other, but things have calmed down a lot since the capture of a few drug kingpins in February. Ciudad Juarez, on the other hand, has been consistently dangerous for the past couple of years.

I didn’t know [the embassy employee or the spouses of employees who were recently murdered in that city] personally, but many members of my Mexican staff here in Tijuana did, so those brutal executions have sent a chill throughout our consulate community.

I do think the US media overall does a poor job of reporting on this complex situation right on our border. In my opinion, it has a lot to do with the priorities of the major US news outlets. They send dozens, maybe hundreds, of correspondents to live in and report from places 6,000 miles away—like Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia—but not one single resident American correspondent here in Tijuana, where a vicious struggle between a friendly foreign government and powerful narco-cartels is taking place just 20 minutes from downtown San Diego.

This must be brutally hard on the Mexican people who want no part of the drug cartels or the violence. Any personal observations?

The vast majority of Mexicans are peaceful, law-abiding people who are appalled by the savagery of the cartels. When you get to know Mexicans who are undertaking huge efforts to improve the quality of life here, you really feel their pain at how this internal war has affected their country.

How is this likely to affect US-Mexican relations in the coming years?

Security issues are already dominating the bilateral agenda between the US and Mexico, and this is probably going to be a major theme in our relationship for a long time. What’s different—and refreshing—since the Obama administration took office is the candid willingness to acknowledge that we share responsibility for this mess because the US market for illegal narcotics fuels the cartels and because lax US gun laws enable the cartels to arm themselves with arsenals of military-grade weaponry. I expect that the new thinking about “shared problems that need shared solutions” will lead to excellent cooperation between the US and Mexico in coming years.

Any advice for Americans thinking of visiting Mexico these days?

I would say they should read carefully the travel warnings that we issue at the State Department. Most people react to the mere existence of a travel warning, but it’s important to see what it actually says. Mexico is a big, diverse country where security conditions vary widely from region to region. The current warning advises Americans to defer travel to certain other Mexican border states, but not here. The governor of Baja California frequently reminds me that my hometown of Baltimore has a higher murder rate than Tijuana!