“Camp Nou became my living room.”

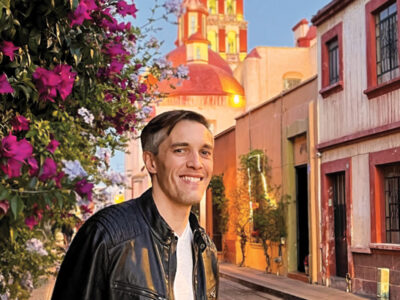

By Andrew Pollen

When Emili told me it would cost 600 euros to rent an abono at Camp Nou—a season pass at the home stadium of FC Barcelona—I was as giddy as a kid being given a puppy. It was 2011. Barcelona had just been crowned kings of Europe by winning the Champions League with a Lionel Messi-led squad widely considered one of the greatest of all time. A handshake agreement with the abono’s rightful owner, a new father who wanted someone trustworthy to keep his seat warm for the season, would entitle us to a Row 15 view of Messi, Pedro, and David Villa feeding off the midfield wizardry of Xavi, Andrés Iniesta, and Sergio Busquets—three of the most sublime passers ever to suit up.

It felt like winning a lottery. Most abonos are passed down from generation to generation. A few hundred turn over every year—but the waiting list was 10,000 deep. And even joining the end of that queue was an ordeal. You had to turn up at the club offices for an in-person interview, and then repeat the process annually lest you lose your place in line.

Without hesitation, I told Emili I was all in.

The two of us had met in 2006, during my semester abroad as a Penn student. At that time Barça were the reigning European champions and Messi was a precocious teenager. I went to three matches at Camp Nou that year. My budget dictated the cheapest tickets high in the nosebleed sections of the stadium’s outer bowl, which were often half-empty. Even an attendance of 65,000 was only two-thirds of cavernous Camp Nou’s capacity, and the 2006–07 campaign turned out to be underwhelming. But I was sitting at the perfect angle behind the goal when Brazilian legend Ronaldinho curled an incomparable free kick into the upper right corner against Zaragoza on November 12, 2006, and I was hooked. Cheap seats to contests against mid-table opponents were all well and good, but I left Catalonia wanting more—Champions League matches and El Clásicos against rival Real Madrid.

Fast forward to 2011 and our abono included entry to all Barça’s league and cup competitions, even the prestigious Champions League. Barça B, the reserve team, was also on the table—which was nothing to sneeze at since they were one of the better sides in Spain’s second division.

With so much football to watch, I learned to optimize: the shortest route from the metro to my seat; where to stop en route for a bocadillo; how to sneak in a beer if I fancied one; what to wear given the wind chill. I familiarized myself with the cheers—and ditto the heckles, especially for Sergio Ramos and Pepe, the villainous defenders for Real Madrid. I learned the second verse of the Barça hymn.

Camp Nou became my living room, a place to drop by on a whim. Sometimes I popped in between engagements for half an hour, arriving 15 minutes late or at halftime to avoid the crowds. If the contest was dull, I did homework. I was now an MBA student at Barcelona’s Esade Business School.

As the season progressed I cataloged the characters in our section. In front: the referee hater. “Fill de puta, collons!” “You’re blind!” “Your mother!” Regardless of the scoreline, his repertoire married ingeniously foul language with bloodthirsty relentlessness. On the right: the cold-shoulder couple. He tuned in to the radio broadcast but she didn’t. They attended the matches together—who could say why?—but hardly spoke. A few rows back, an elderly gentleman furtively soundtracked the match on his trumpet. I ran into him one day at a neighborhood olive oil festival. “Ja no em deixen passar la trompeta!” (“They’re not letting me take in my trumpet anymore!”), he sobbed in a state of drunken bereavement. I got his next round and commiserated about the cruel struggles honest men faced squirreling brass instruments into football grounds. I learned later that this man was Ferran Estrada, a diehard culé who ran for club president several times, without the slightest success.

Being a Camp Nou denizen made me feel more connected to the city than ever. Barça truly is “more than a club,” as its slogan asserts. It’s an extension of the city’s personality: proud, modern, artistic, a little uptight. Sinking into the rhythms of Row 15 deepened my immersion, which stretched from joining a neighborhood youth organization to learning Catalan well enough to pick up on the way the Franco dictatorship’s ban on regional languages had smudged the syntax of Catalonians of a certain age.

Much has been written elsewhere about Messi, who won a club-record 34 trophies for Barça and the 2022 World Cup with Argentina before taking his otherworldly talents to the US and Inter Miami. Watching him live, his close control, speed, vision, and finishing were simply breathtaking. Once or twice a game he did something that made the Camp Nou faithful bow and chant, “Messi, Messi,” in a descending minor third. As far as I could tell, this adulation was invented for Messi and reserved for him alone, save for its occasional extension to the majestic Iniesta.

Yet Messi’s sheer magnificence was beginning to warp Camp Nou—and by extension the city itself—in unsettling ways. An explosion of football tourism threatened to eclipse the organic atmosphere that had enraptured me in 2006. Fueled by the rise of budget airlines, Airbnb, and online ticket brokers, tourists descended upon Barcelona on package deals that included a Barça match. Although these trends affected all of Europe, Barcelona had the added advantage of sunshine, cheap sangria, and an enormous stadium where local fans, spoiled by success, were happy to sell off some of their tickets to fat-walleted foreigners seeking a glimpse of the Great One.

After earning my MBA and leaving Barcelona I fell more in love with football, if that was possible. Whenever an opportunity arose, I canvassed the continent devouring whatever I could—top-flight matches across England and Spain; Champions League tilts in Porto, Valencia, and Villarreal; and even more exotic fare, like the English second tier and Spanish third tier. But nothing compared to the cauldron of Camp Nou on a significant night, with 95,000 rising as one to serenade Messi, Iniesta, Xavi, Puyol, and many other all-time greats.

Yet no cauldron boils forever. Back at Camp Nou in 2016 to watch Barça trounce Getafe 6-0, I was struck by how the listless crowd barely mustered polite cheers for the goals. “A comfortable rout of a hopeless opponent,” chuffed one fan blog, perhaps unaware of the extent to which the same adjectives also described the home supporters. Complacency seemed to permeate every level of the club—which soon began to crumple beneath staggering financial debts incurred in pursuit of marquee talents it hoped would reenergize a fan base that yawned at anything less than beautiful football and spectacular results.

Turning to Joan Laporta, a Spanish politician who’d led the club at the beginning of the Messi era, FC Barcelona tackled its financial crisis with a series of compromises that, like all such compromises, mixed undeniable prudence with a prick of pain familiar to any American football fan who wakes up one day to discover that the Citrus Bowl has been renamed after Cheez-It crackers.

Emili insisted to me that Laporta was defending the club’s culture against the worst depredations. And far be it from me to question my oldest Barça buddy. Yet on my most recent visit to the newly christened Spotify Camp Nou in 2022, with Emili and my friend Eric Schwartz C’08, the experience was more commercial than ever. We marveled at the slick Estrella Damm-branded fan zone; the new restaurants and shops; the penalty-kick simulator where kids can face a robotic goalie for five euros. Each element was doubtless an obvious business proposition, but the corporate vibe felt novel in a country where many stadiums retain the gritty, improvised feel of a county fair—the very atmosphere that pulled me into football fandom, and Barcelona itself, to begin with.

They say you can’t step in the same river twice. Yet I can’t help thinking that Catalonia’s flagship football club is too deeply interwoven with its host city to fall victim to the flavor of any one moment. What’s new gets old, what’s old becomes new.

Messi, after all, decamped to Paris Saint-Germain in 2021—the same year that the trumpeter Ferran Estrada, aged 87, again ran for Barça’s presidency. If you want a beer while you watch, you’ll still have to sneak it in. And the old cheer continues to rain down from Camp Nou’s nosebleeds: “Ser del Barça és el millor que hi ha”—Rooting for Barça is the best thing there is.

Andrew Pollen C’08 W’08 lives in Alicante, Spain. FC Barcelona, now coached by Xavi, won its first league title in four years in 2022–23.