Lynn Meskell believes UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites list “generates more conflict than cooperation.”

Around the world, more than 1,150 landmarks have been designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as World Heritage Sites. These range from physical structures like Stonehenge and the Taj Mahal to natural wonders such as the Great Barrier Reef and Yellowstone National Park.

The sites are nominated by the country in which they are located before being certified by a vote of 21 UNESCO elected member states and gaining some legal protections and financial assistance.

The process, however, has too often “become politicized, especially when you have Russia and China as major players” after the US, a founding member, withdrew from UNESCO at the start of 2019, notes Lynn Meskell, Penn’s Richard D. Green Professor of Anthropology. Ukraine, for instance, has seven sites on the UNESCO list and Russia claims to have touched none of them while waging war on the country during the last 18 months. But “this is why Russia feels so entitled and no one can stop them from destroying many other buildings and sites that also have meaning to Ukrainians,” says Meskell, a Penn Integrates Knowledge (PIK) professor with dual appointments in anthropology and historic preservation. Recently, Russia tried to block Ukraine from nominating Odesa on an emergency basis; the city’s historic center was nevertheless successfully inscribed as a UNESCO endangered World Heritage site in January, giving it access to international assistance to protect property and, if necessary, assist in its rehabilitation.

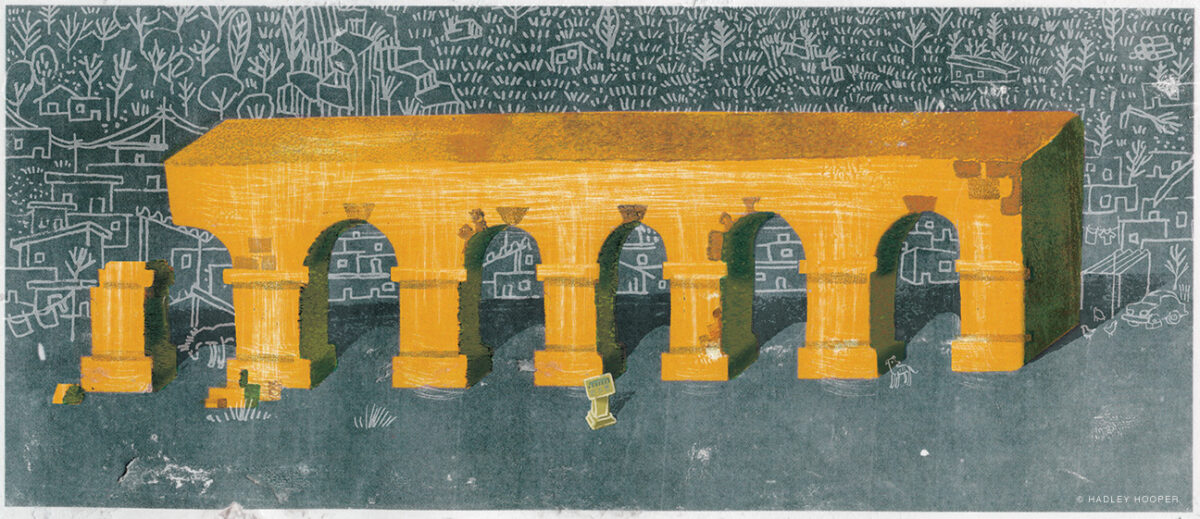

The idea of a World Heritage list is rooted in 1959 pleas by the governments of Egypt and Sudan for UNESCO to help protect and conserve monuments and sites threatened by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. It wasn’t long before other nations began submitting similar requests. But what began as an idealistic enterprise increasingly looks like a tangled mess wrapped inside a knotty web of geopolitics, colonialism, and even war mongering, notes Meskell. “Since the rise of the Islamic State, the international community has been forced to confront the deployment of cultural heritage as a [new weapon],” she says. “The protection, destruction, utilization, and manipulation of heritage by state and non-state actors has become the new normal.”

Meskell’s research investigates what makes cultural heritage “such a strategic resource and target in international conflict,” she continues, adding that in some cases countries attempt to use the list “to self-aggrandize and rewrite history” by nominating war sites like the Battle of the Somme and genocide sites in Rwanda. “It turns the UN into a forum for aggrieved nations, not really the world peace model it set out to be.”

Meskell also believes that UNESCO elevates the interests of “tourists or art historians or preservationists” above those of people who actually live among the heritage sites. “It’s staggering to me that no one asks the people on the ground for their preferences on what to modernize, restore, memorialize,” she says.

In February, Meskell presented research she conducted with Witold Henisz, vice dean and faculty director of Wharton’s ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) Initiative, to a panel of NATO-member delegations. With support from the Penn Global Engagement Fund, Meskell and her team examined public sentiment at World Heritage Sites and found that “having this list generates more conflict than cooperation, which was its initial reason for being,” she says, stemming mostly from intergovernmental and labor issues. “People feel aggrieved that sites haven’t delivered on the benefits that were promised—like, more jobs, for instance—and as such a great deal of hostility is aimed at listed sites. The international community has poured money into sites while citizens are starving. That just doesn’t make a lot of sense in the eyes of those who live in those nations.”

Meskell also recently completed, with colleagues from Princeton, Duke and Australia’s Deakin University, surveys of 1,600 citizens each in Mosul, Iraq and Aleppo, Syria, about the priority of heritage reconstruction in the context of health, education, employment, and security concerns. “It won’t surprise people that it turns out to be quite a low priority,” she says.

A native Australian, Meskell entered archaeology early, embarking on a journey right after high school that took her to some 35 countries with a focus on touring major archaeological sites. “When I look back, I see that I’ve always looked at the field with a questioning eye,” she says. “I’m interested in its contemporary, political life.” Her first book, Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East (1998), published shortly after she completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge, set the tenor of her relationship with her chosen profession. Her most recent book, A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace (2018), is an institutional ethnography that more specifically addresses the challenges and relevancy of the World Heritage program.

She characterizes the collaborative ‘one world’ ideal of UNESCO, which was founded in 1945 in the wake of two destructive world wars, as an outdated vision of heritage rooted in “a mid-century, romantic and Eurocentric perspective.” She doesn’t advocate for getting rid of the list but believes that UNESCO needs to “develop new instruments that [can combat] heritage weaponization, and it also needs to diversify and work with other [community-based] agencies” to better prioritize local concerns.

Meskell will continue to conduct field research around the globe (this summer in Jordan, where she’ll study heritage organizations in the region), on top of a packed schedule of keynotes and summits, her position as a curator in the Near East and Asia sections of the Penn Museum, and this fall’s anthropology and historic preservation course, “World Heritage in Global Conflict,” which will explore the political tensions stemming from UNESCO’s World Heritage list.

“Coming to Penn has changed the research I do, what’s possible for me to investigate, and the way I approach it,” says Meskell, who’s had fellowships with the Wolf Humanities Center and Perry World House. “I am super exhausted, but it’s because the PIK position has opened so many doors.”

—JoAnn Greco