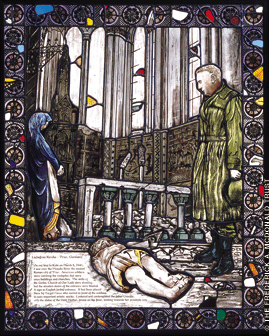

Former Army Chaplain Frederick Alexander McDonald inside the bombed-out Liebefrau Kirche in Trier, Germany (left) and in the artistic imagination of Peter Eichhorn (right). “I entered and contemplated the fallen Crucifix, with the statue of the Holy Mother, prone on the floor, looking towards her prostrate son.”

Architectural historian Robert Bevan has written of the “horror and fascination at something so apparently permanent as a building, something that one expects to outlast many a human span, meeting an untimely end.” September 11 well taught us that the crumbling of iconic architecture is powerfully symbolic, but the strategy goes back to the Classical era, and more recently to Hitler’s “Baedeker” raids against England’s historic tourism sites. Those raids are in fact referenced in “Remembered Light: Destruction and Resurrection (Glass Fragments from World War II),” on view at the Arthur Ross Gallery through June 15. The show features 25 “windows,” many suspended from minimalist steel frames, that incorporate shattered glass collected from Europe’s bombed churches. The vision of San Francisco stained-glass artist and restorer Armelle Le Roux, “Remembered Light” brings together 13 artists whose mission was to use stained-glass fragments from a specific place of worship to fashion a narrative of its destruction.

“They were given a tape and an envelope, and that was it,” laughed Le Roux in a talk at the Ross Gallery in late March, when the exhibition opened. “What do you do? Where do you begin? It was totally up to each individual.”

Out of the tapes came the strong voice of a 91-year-old former U.S. Army Chaplain, Frederick Alexander McDonald, reminiscing about the two-dozen churches he had visited while ministering to soldiers in 1944 and 1945. Out of the envelopes spilled glass shards—the color of amethysts and lapis lazuli, of sapphires and emeralds—he had picked up from the ruined sanctuaries.

Any beachcomber who’s ever stooped down to more closely inspect a glowing flotsam of sea glass mixed in the sand will understand what drew McDonald to save the fragments. But more than sparkling mementos, these jagged, jewel-toned bits are the fractured souvenirs of a “witness to history,” says Le Roux. “Fred was a collector, and once we started working on formally putting together this project, he’d constantly be pulling something out of his pocket to fill in a story.”

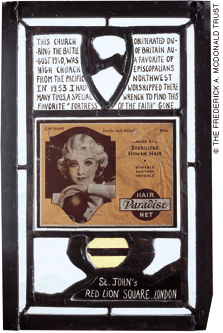

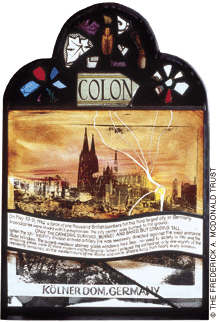

Shattered inspiration: Liebefrau Kirche in Trier, Germany (left). London, England, St. John’s, Red Lion Square (middle), by Armelle Le Roux. Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, Germany (right), by Irmigard Steding. “Only the Cathedral survived, burned and baked, but standing tall.”

“Remembered Light” began in 1999, when friends and family convinced a then-ailing McDonald (he died in 2002, at age 92) to dig out his collection and do something with it. The project landed in the hands of Reflection Studio, an Emeryville, California stained-glass restoration outfit where Le Roux worked.

“That he had kept the shards for 50 years separated in different envelopes convinced me that the glass and the story had to stick together,” she says. “This was not one large story, but a collection of smaller, intimate ones.”

So while glass is the crux of the exhibition, each window is informed and deepened by McDonald’s memories, through a few sentences written into each work.

“I entered and contemplated the fallen Crucifix, with the statue of the Holy Mother, prone on the floor, looking towards her prostrate son,” he wrote of Liebefrau Kirche in Trier, Germany. In response, Trier-born glass artist Peter Eichhorn, in one of the exhibit’s more literal works, places 43 shards around the border of an image of McDonald in combat boots staring forlornly, helmet in hand, down at the scene described.

Several of the artists’ statements are as powerful as McDonald’s simple impressions. “When I had these ancient shards—the remnants of bombed-out windows—in my hands, they felt to me like thorns,” writes Narcissus Quagliata of his piece commemorating the Cathedral of St. Stephen in Metz, France. The work intertwines 33 shards—one for each year in Christ’s life—into a vivid crown of thorns, backed by fiery panels the color of blood. “It was an honor to … place them against the light again, where they really belong,” Quagliata writes.

Le Roux’s Coventry piece situates a silk-screened photo of the severely damaged St. Michael’s Cathedral at the bottom quarter of the work, its black-and-white somberness relieved by a few amber and ruby shards sparkling in burned-out bays. The rest of the composition is dramatically devoted to a cascade of new stained glass rising to the sky.

“This window is [about] reconciliation,” Le Roux’s commentary notes. “The bombed cathedral from which rises the glorious stained glass of the new one.”

Not all of the creations—or the churches they pay tribute to—aspire to such heights. One of the most poignant works uses a sandblasted glass background to mimic a wash of ultramarine watercolor sky. Here Le Roux, who crafted about half the works on display, lines up 11 citrine triangles of glass from an unidentified Maastricht sanctuary. The pieces reminded her of markers for fallen soldiers, comments Le Roux, a Frenchwoman who grew up not far from the Normandy beaches.

The presence of so much glass placed in the context of war brings to mind, almost as a matter of course, an early event in Hitler’s campaign: Kristallnacht. Besides ruining the livelihoods of thousands of Jewish shopkeepers, the shattered glass that pierced the cold German and Austrian night in November 1938 resulted in the destruction of nearly 300 synagogues. But while the fate of religious architecture during the horror of wartime is a central theme, there’s more going on here. As its name suggests, “Remembered Light” is about memory and faith, color and light—and their power to inspire and impel in the face of great loss.

“The city center [of Cologne] was burned to the ground,” wrote McDonald. “Only the Cathedral survived, burned and baked, but standing tall.”

— JoAnn Greco

To learn more about the project, visit rememberedlight.org. Eventually the organizers hope to install the windows in a new wing to be built at the Spanish Colonial Revival chapel in San Francisco’s Presidio, a decommissioned military base now part of the National Park system.