Penn’s recently approved master plan envisions playing fields and green space where there are now parking lots; the transformation of Walnut Street’s “dead zone” into a mixed-use mecca; new housing, research, and athletic facilities—plus river views and a seamless connection between University City and Center City.

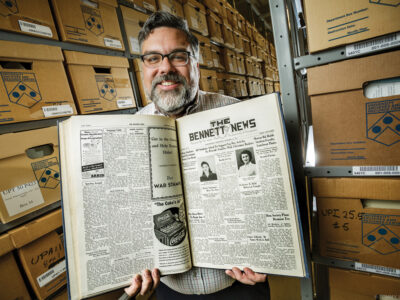

By John Prendergast | Photography by Bill Cramer

“It is only possible for us to move to the next level of eminence if we have the space to do so,” Penn President Amy Gutmann is saying in her College Hall office. She’s talking about the University’s long-anticipated acquisition of the “postal lands”—24 acres east of campus bordering (almost) the Schuylkill River, currently occupied by the former main branch of the U.S. Post Office, a postal annex and associated maintenance buildings, and lots and lots of cracked asphalt and weedy patches—which is scheduled to become final this spring.

“If we were contained physically, we could not engage the way the Penn Compact aspires to engage,” she adds, referring to her program to increase access to the University, foster interdisciplinary research and teaching, and to engage locally and globally. “We need more housing for our students, we need teaching and research facilities, and if we’re going to continue to have the increasingly excellent relationship with our local community, we need to create an ever more vibrant presence, not only for Penn, but for West Philadelphia and Philadelphia.”

The added space will allow Penn to build needed academic and athletic facilities, while also creating more green space and recreational fields “not only for our students, but for the community as well,” she says. At the same time, the construction of new dormitories will bring students back to the campus core, opening “more opportunities for our neighbors, faculty, staff, and people unaffiliated with Penn, to have nice residential opportunities in West Philadelphia.”

On the table in front of Gutmann, along with some notes for our interview, are a couple of copies of a document titled Penn Connects: A Vision for the Future describing Penn’s new master plan for the east-campus development, approved by the trustees in June. That this “executive summary” is 25 pages long gives some idea of the scope of the project.

The product of 15 months of research and analysis by Penn planners and project consultants Sasaki Associates, with input from a wide range of University constituencies and building on a 2001 planning effort, the document lays out a “phased development strategy for the next 25-30 years.” (Interested readers can download a pdf of the document at www.evp.upenn.edu.)

To take advantage of the ripple effect of an acquisition of this magnitude, planners also looked at ways the new space could affect future development of the existing campus—with particular attention to concentrating academic activities close to the historic core of the campus. Among the key elements:

• Most of what are now surface parking lots (about 14 acres) will be replaced with major new athletic fields and passive green space, and the area around the Palestra and Franklin Field will be redeveloped into a plaza and promenade that will extend Locust Walk to the new fields and eventually—by way of a proposed pedestrian bridge—across the river to Center City.

• Walnut Street between Center City and campus—variously described as a “void,” “dead zone,” or “industrial wasteland”—will be developed with a mix of retail, hotel/conference, residential, and office space, plus research and cultural facilities, lining what will become a striking new entrance to the campus.

• The highly congested area around the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the medical campus south of Spruce Street will be improved with the addition of a major new green space where the Penn Tower now stands. Future medical expansion will also be provided for.

• Taking advantage of the differential between the elevated streets at Walnut and South, some 4,600 parking spaces will be added in four garages built below the street level on the floodplain. The garages will form the base for new construction—likely to be commercial development on Walnut, and sports fields at South, adjacent to a reconstructed South Street Bridge. A variety of road improvements will provide access and ease traffic flow.

• New construction proposed in the plan within the existing campus footprint includes a 350-bed college house on Hill Square added to Hill House to create a new quad; an approximately 100,000-square-foot facility for nanotechnology research adjacent to the Laboratory for Research on the Structure of Matter (LRSM) on what is now a parking lot on Walnut Street; and a new field house north of the Palestra on the current site of the Levy Tennis Pavilion. Further in the future, the plan contemplates potential future redevelopment of non-historic structures—such as the Franklin Building—to better consolidate academic activities in the heart of campus, with administrative functions relocated east.

It’s no secret that the University has a major capital campaign in the wings [“Whence the Money?” Mar/Apr], and the implementation of many elements of the master plan will be closely tied to achieving the University’s fundraising goals for that effort. Another big chunk of the estimated cost will come from the Health System. And other parts, particularly the mixed-use developments on Walnut Street, will be financed through a variety of leasing arrangements similar to ones the University has used in the past for the Left Bank apartments and projects now under way on Chestnut Street at 34th and 40th streets.

The overall price tag is an estimated $6.7 billion, spread out over the 30 years of the plan’s four projected phases. The first two phases, which will take about a decade to complete, should cost $3.8 billion in current dollars, according to Craig Carnaroli W’85, Penn’s executive vice president. Of that, the University (non-Health System) share will be about $900 million, anticipated to come from fundraising (44 percent), the University’s operating budget (18 percent), long-term debt (28 percent), and grants and government support for infrastructure elements (10 percent). Another roughly $1.5 billion will come come from the Health System to support its expansion, and the rest will be “third-party money,” says Carnaroli, in projects involving commercial development.

The plan is organized around what the executive summary calls four “bridges of connectivity”—some purely metaphorical, others physical. These include a “living/learning bridge” on Walnut Street; a “sports/recreation bridge” encompassing the new fields, field house, and Franklin Plaza and Promenade; a “health sciences/cultural bridge” at South Street, where the medical campus and Penn Museum meet; and a “research bridge” to encompass future expansion of the medical campus.

This led to the overall theme of “Penn Connects” for the plan, which President Gutmann embraced with characteristic enthusiasm. “I’ve emphasized from the beginning how important it is to break down silos,” she says. “Another way of expressing that is to connect—to connect our 12 different schools, to connect ourselves even more with the community than we’re doing now.”

“We are living NOW with the flying waste paper of Woodland Avenue, the roar and rattle of traffic at all hours of the day and night … We are the ones who must contend with the eyesores which now dot the campus, —the repellent parking lot at 37th and Woodland Avenue, the shacks which serve as stores along 37th Street, the old dormitories familiarly known as the “barracks” … Anything and everything uses our campus as a thoroughfare.”—Daily Pennsylvanian editorial, May 15, 1937

This excerpt from the DP, reprinted in the Gazette, gives a vivid picture of the campus some 70 years ago—before Woodland Avenue was closed to traffic, Locust Street became Locust Walk, and Blanche Levy Park and other landscaping projects of the 1970s created the College Green and campus we know today. In recent decades, renovation projects in the Quad and the high-rise college houses, the Perelman Quad and Wynn Commons, the Penn Bookstore and Inn at Penn, and new academic facilities such as Huntsman Hall, Levine Hall, and the McNeil Center, among others, have furthered enhanced the environment.

That transformation of the campus “really resonates with people” says Carnaroli, who has been sharing various iterations of the east-campus plan with audiences for months, including presentations to the Alumni Board and Council of Representatives and other alumni groups. “When you show people Woodland Walk from the 1940s and you show what it is today, it plants the seed that positive change is possible,” he adds. “There have been these historic opportunities in the University’s past to embrace change and adapt the campus to the wonderful urban place it has become, and we’ve seized those moments.”

Gutmann takes the analogy back even further—to the early 20th-century expansion after Penn moved to West Philadelphia, when the University became an institution of national note. “Without that expansion, with major building and the creation of the academic core, we would not be where we are today,” she says. “This is, to the 21st century, what the early 20th-century expansion was to Penn.”

Penn has been eying the postal lands at least since the early 1980s, and with increasing interest as postal officials went forward with the relocation of mail-handling facilities to a site near Philadelphia International Airport, but the $50.6 million deal wasn’t made until near the end of President Judith Rodin CW’66 Hon’04’s term in office—and, of course, Penn won’t actually take possession of the land until this spring.

In April 2005, Gutmann appointed a 10-member Campus Development Planning Committee (CDPC) composed of deans and senior administrative staff, and co-chaired by Carnaroli and Penn Provost Ron Daniels. As consultants, the University brought in Sasaki Associates. “Sasaki helped guide the committee as it looked at this in a really comprehensive way,” says Carnaroli, pointing to the firm’s “international experience and global perspective” as well as its strong track record in the U.S. higher-education market (clients include Harvard). The company had also completed a study for the Schuylkill River Development Council, an umbrella group in which the University is involved, looking at both banks of the river a few years ago, which meant they were familiar with the site and the related issues.

An ad hoc committee of trustees was also involved, and the CDPC collected advice and feedback from constituencies representing deans, senior administrators, students, faculty, staff, and alumni. A series of town hall meetings was held on campus last fall, and a student survey was conducted as well. Comments were also invited for an interim report that was published in Almanac, Penn’s journal of record, in February.

“The committee took a great deal of time to ensure broad consultation in its deliberation,” says Daniels. “That meant everything from meeting with various groups, from faculty to alumni to students to staff to constituencies outside the campus, to holding town hall meetings, to doing presentations, to having an interim report, which was an opportunity to do our thinking out loud and to get feedback.”

As a result, Daniels adds, the various stakeholders were able to convey their needs “in a fairly clear and compelling way,” and the final plan is “responsive to a lot of those concerns and dreams for the campus.”

Student interests included housing, athletics, and the preservation and expansion of open green space on campus. “There was the real sense that one of Penn’s defining features is its status as an urban campus, but one that has a significant amount of open space, and there was a very strong concern that, as we thought about development, we were attentive to the need to preserve and create the additional open space,” says Daniels.

The need to improve the eastern entrance to the campus was a sentiment that cut across all groups—“particularly the so-called ‘dead zone’ along the Walnut Street Bridge,” says Daniels—and to ensure that development along the corridor “really created a lively and dynamic campus community that would be on that edge of the campus.” Such concerns were especially prominent among graduate students, who are more likely than undergrads to live in Center City, and must brave that now rather bleak trek every day; they also favored additional graduate-student housing in the area.

Among the faculty, there was a strong response to the need to expand “core academic space,” with the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School of Medicine, and the life-sciences component within the School of Arts and Sciences being particularly “concerned about the need to expand the core research space, because that was a priority, clearly.” The need to provide more cultural space was also recommended.

Alumni concerns tracked the interests of a number of other constituencies, Daniels adds. “They were concerned about the linkages to Center City, concerned about the open space, concerned about the athletic facilities, student housing, so there wasn’t one particular issue that came from them.”

Once planners had a sense of the perceived needs, they took a look at how they could best be met by the space, given site conditions, financing, and other issues. Besides the recently acquired 14 acres now occupied by surface parking, planners also took into consideration another 18 acres already owned by the University—now taken up by sports fields, the Class of 1923 Ice Rink and Levy Tennis Pavilion, and a few smaller plots.

If the east campus were a movie, its title might be Floodplains, Trains, and Automobiles. Besides the Schuylkill Expressway (I-76), which runs along the river, the site is crossed by ground-level train tracks used by SEPTA’s regional rail lines and AMTRAK’s Northeast Corridor trains, and the CSX “Highline” freight railway, elevated some 60 ft aboveground on stone and steel supports. Much of the land also lies within the floodplain, and uses need to accommodate periodic flooding when the Schuylkill rises above its banks.

“You have a classic ‘brownfield’ situation—a transportation corridor, a single-use zone, that today is seen as a place of great value,” says Sasaki President Dennis Pieprz, who headed the team working with Penn. “The gateway to Penn is the back of a postal facility, highways, rail lines, parking lots, very poorly defined streets.”

The situation wasn’t much better up above, he adds. “Walnut Street just a bit further [West] is great, and as you go into Center City, Rittenhouse Square is one of the most remarkable urban districts in America. Yet there’s this void here. Our work was very much about making urbanity, extending the relationship of the University to the river, to Center City, so that people would feel welcome coming into the University and coming into Center City.”

The plan as ultimately approved evolved through “many, many diagrams and drawings,” Pieprz says. “We had six very different concepts early on, some very radical—decking of everything, creating a whole new edge of buildings—and we slowly evolved the plan to its current state through simply [asking]: What is the most achievable? What creates the most successful urban environment? What gives the University the flexibility it needs?

“Some schemes required very heavy investment upfront in ways that you can’t easily justify, so we eliminated those,” he adds. “We have a lot of infrastructure passing through the site areas. You have the multi-level and floodplain issues. It’s a very complicated thing.”

Architectural renderings courtesy Sasaki Associates

While a number of elements in the plan are contingent on funding, logistics, or other factors, the very first thing the University will do, once it takes possession and gets all the necessary clearances, is to dig up the asphalt and turn it into green space. Reversing the lyrics of the old Joni Mitchell song, Penn will tear up “parking lots to put up a bit of paradise,” says Gutmann.

“This is not 20 years out, this is two years out.”

Fields for softball, soccer, and multi-purpose recreation are envisioned, along with more purely park-like areas. Planners estimate that, by about 2010, campus green space will have increased about 20 percent as a result. Landscaping will create a series of grass terraces, accommodating flooding in the low-lying areas and rising to the height of the bridges, where a boardwalk will be built to link Walnut and South streets and provide views to the river, past the train tracks and highway.

Right now, pedestrians trying to reach, say, Bower Field, must pass by the Hunter Lott Tennis Courts in front of the Palestra, walk through the parking lot between the Hutchinson Gym and Franklin Field, and traverse a narrow footbridge and circular stairway—only to find themselves in another parking lot adjacent to the Levy Tennis Pavilion. In the future, the approach to the new fields will serve to extend Locust Walk to the river’s edge while creating a new frame to highlight the Palestra and Franklin Field.

The tennis courts will be moved to Highline Park at 31st and Chestnut to make way for a new open space—a sunken lawn with shade trees and seating areas—that will improve the view of the western façade of the Palestra, while the parking lot will become a new plaza leading to the sports and recreation fields, reached by a series of ramps and stairs bridging over the existing SEPTA train tracks.

Along with renovations to the Palestra and Hutch, construction of a new field house will include a deck over the SEPTA line connecting the area to Walnut Street to the north, and also extending to South Street. Immediately adjacent to the South Street bridge would be an 800-car parking garage below the bridge level, with a multi-purpose field built over the top level of the parking deck. Besides adding recreational space, this would also let people get a good look at Franklin Field’s eastern façade and create a “green gateway” to the campus from South Street. The deck might later be extended over I-76.

Other plans for the South Street corridor include a new cultural building to the west of the Hollenback Center and a possible addition to the Penn Museum, following the demolition of an existing parking garage.

“If I had to pick the single most creative part of the plan for Penn and Philadelphia, it would be the walkways—extension of Locust Walk and the extension of Woodland Walk through the campus, connecting West Philadelphia and Center City by your sight lines,” says Gutmann. The reality of the Penn Connects theme is “made most vivid in the plan to get a natural extension of Locust Walk from 34th Street, the center of campus, to the river.”

Besides making aesthetic sense, she adds, it also reinforces community building and makes efficient use of resources. “Franklin Field and the Palestra are iconic buildings. We want to keep those buildings up,” she says. “And if you want to keep them up, you have to make them accessible to people, and they’re not. They’re hidden to people unless you know where they are. So we want to open them up, and invest in our athletic and recreational precinct in a way that will be accessible to more people.”

Extending the walkways also will expand the sense of campus, she notes. Though technically contiguous, the campus doesn’t always feel that way because of the obstacles to walking through it. Remove those obstacles by opening up the space “and it becomes an even more beautiful and vibrant campus,” she says. “I emphasize vibrant, because the vibrancy of urban life has to do with use, and we have large parts of our campus that are not well used because you can’t get to them.”

“The other thing which is very important is to create a lively edge along Walnut Street, which is now an industrial wasteland as you come into Penn,” says Gutmann. Under the plan, this area will emerge as “the consummate mixed-use neighborhood,” she adds.

In considering the Walnut Street corridor, the plan looks at development west and east of the Highline—a divide currently marked, as regular commuters know, by the peeling UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA painted on the overpass.

To the west, plans call for construction of a 200,000-gross-square-feet (gsf), 350-bed college house around Hill Square. Combined with Hill House, the buildings would create a new quad that would preserve about 70 percent of the existing open space, as well as the text-based sculpture by Jenny Holzer commemorating 125 years of Women at Penn, dedicated in 2003. The new college house will “create another wonderful quadrangle on campus, leaving the center of Hill Field green, but creating a structured space that is more usable than the space now is,” Gutmann says.

Providing research space for Penn’s burgeoning expertise in nanotechnology [“Small Technology, Big Promise,” May/June 2005] is another priority. The plan proposes a 100,000-gsf facility on the site of a parking lot just east of the LRSM building. “We have a School of Engineering and Applied Science that is on the move,” says Gutmann. “The east campus allows us to build a nanoscience building on the east without isolating it, but rather, it will be integrated into our campus. At the same time it’s going to help foster more technology transfer in Philadelphia.”

In general, developments along this stretch of Walnut are expected to emphasize “learning, research, and support amenities,” according to the plan document. Other academic or research facilities could be developed on the other side of Walnut, in the area north of the Palestra. The ice-rink site might also be redeveloped.

East of the Highline, things get more, well, lively. Planners estimate that about 1.7 million gsf of development is possible, mixing retail, restaurants, and residential space; a possible hotel and conference center; cultural and performance centers; and offices and more research space. This will all happen at the height of the Walnut Street Bridge, constructed on a deck with parking below. Eventually, the plan envisions 30-story mixed-use and 15-story mixed-use and research towers above the deck, but the first building will likely be a “cultural gateway” at the eastern edge. “We’d like to create right off the bat some kind of artistic edge along Walnut,” says Gutmann, “even before all the development is possible.”

More commercial development is likely for the blocks north of Walnut also included in the parcel. As for the historic Post Office building itself, only the branch operations will be kept open. The University is in negotiations with potential tenants—the IRS has been mentioned as one possibility—to occupy the existing office space in the building.

Even without the traffic that frequently blocks it,Spruce Street has historically been both a physical and psychological barrier between the University and its Health System, and one that Gutmann has taken pains to bridge. “A lot of the doctors have commented to me that just over the last two years we’re breaking down what they call the ‘Spruce Street Divide,’” she says, through efforts like interdisciplinary programs and events that bring doctors and other faculty together. “Now we’re actually going to break it down physically by making it easier to walk from our core academic campus into the medical and Museum precinct.”

Though they are “right next to each other,” the medical campus and Penn Museum don’t mesh well at all. The Museum’s entrance is not conducive to drawing people in, and it also isn’t near where you enter the medical precinct, Gutmann notes. Architect David Chipperfield, who is working on a master plan for the Penn Museum; Rafael Viñoly, architect for the Center for Advanced Medicine, now under construction on the old Civic Center site; and Sasaki’s Dennis Pieprz are working to “create in this area a cultural/medical mecca, where it will be much easier to walk and drive to the CAM, to a hospital, and at the same time make use of our Museum,” Gutmann says. “That feasibility study is already under way, so we know we have a way of creating better driveways and walkways here.”

Eventually, the existing Penn Tower, now used mostly for medical offices, would be demolished and replaced with a new plaza, providing some welcome open space in what is perhaps the busiest corner of campus, and also improving access to the SEPTA line. A pedestrian bridge over the SEPTA tracks and under the Highline would link the plaza to the River Fields area. There, anticipating future medical expansion, the plan identified a potential 1.55-million gsf of space for this purpose. As along Walnut Street, the buildings—four 15-story towers—could be constructed over an 1,800-car parking garage.

The medical/museum precinct “is contiguous to the athletics and recreation, which is contiguous to Walnut Street, so there are going to be multiple corridors to move from Center City to West Philadelphia,” notes Gutmann, “so it will be functional as well as beautiful. It’s a great combination.”

“The sky is always blue and the birds are always flying,” says Craig Carnaroli, referring to the idyllic world of artist’s conceptions. The business of transforming the watercolors into reality is another matter.

“It has to do with priorities, and also what’s actually possible,” says Gutmann. “You have to do some things before you can do others, so the priorities have to include housing for students, research facilities for faculty, recreational/green space for everybody—because we’re committed to responsible urban development.”

Money will have to be raised for projects like the college house, research facilities, and new field house. “We need to have commitments before we build things,” Gutmann notes. “We have a lot of enthusiasm for that, and our fundraising in the last two years has gone spectacularly well,” with fiscal year 2006, which ended June 30, setting an all-time record for Penn, she adds. “So, I’m optimistic that we will be able to raise the money.”

While gifts will also support development of the mixed-use neighborhood along Walnut Street, it also includes “at least as much, if not more, that we will [fund by] entering into commercial leasing arrangements,” with interested private developers, she adds.

Beyond the most general information on square footage and massing, the plan did not address the architecture of specific buildings. But Gutmann has an idea of what she wants.

“A great university needs great architecture, and I’m committed to making sure we have distinguished architecture on our campus,” she says. Styles will vary, with the site being one imporant factor—a building on Walnut Street might have a far different style and materials than one nearer the campus core. Whatever the style, though, “I want to make sure the buildings that are built to last are all distinguished in their own way,” Gutmann says. She cites as examples Skirkanich Hall, the bioengineering building now under construction designed by “rising architectural stars” Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, and Viñoly’s CAM design, which are successful both aesthetically and functionally.

“I want to marry form to function in an imaginative and lasting way for a lot of our buildings,” she says. “That’s part of what attracts people to an urban campus—a variety of architectural forms that serve practical functions. So I imagine different styles and designs, as many as there are functions and different sites on this multi-hundred-acre campus.”

Approval of the development plan by the trustees prompted a flurry of stories in the local media over the summer. One striking feature—in marked contrast to Penn’s own expansion efforts in the 1960s, and current programs at other urban institutions like Harvard and Columbia—is that so far no voices have been raised in opposition, The Philadelphia Inquirerrecently noted.

“It now seems so natural, this plan; it seems absolutely the future,” says Gutmann. “Everybody knew it was a great opportunity, but nobody knew at the beginning how much we could make of it. Now we’re poised to move forward—and we have a phasing plan which makes sense.”

While specific needs may change as new opportunities arise, “there’s a place for everything in this plan,” Gutmann adds. “When we create more housing or another research building, when we lease land for retail or a restaurant or a new hotel, we can be confident that we are putting it in the right place, not just for today but for decades to come, because it has such great connections from the campus to Center City.

“It’s that sense of fluidity and of welcoming people in and enabling people to make better use of everything that Penn and Philadelphia have to offer that makes this such an imaginative plan.”