Penn’s ambitions have always strained its (relatively) modest resources. How the University keeps up with the Joneses—and the Harvards, Stanfords, and Yales—in a very expensive neighborhood.

By John Prendergast | Illustration by Rich Lillash

“As a University, we are looking forward with bright anticipation and steadfast courage, for while we have never been so fortunate as most of our sister universities, east or west, in accumulated wealth, and while we do not know for sure when the money for our urgent needs, shall come, we have proved the Franklin’s dream was not of baseless fabric.”

—Editorial, “The New Year,” Old Penn, December 16, 1914

Allowing for the early 20th century’s more florid prose style, it’s not hard to imagine a sentiment similar to that 1914 editorial being voiced today.

The University of 90 years ago was expanding physically, blazing new intellectual trails on campus, and extending its influence locally and on a global level. The Old Penn editorial goes on to boast of the “matchless equipment” and international reputation of the dental school’s new Evans Institute at 40th and Spruce streets, which would be dedicated later that winter to much fanfare, and also of the new graduate school (in which, it was hoped “the summit of truth shall be like a mountain peak in a clear sky, not hidden in a fog of words”). The establishment of the School of Education had been announced earlier that year; Wharton’s new “extension schools” in Harrisburg and Reading, Pennsylvania—that era’s Wharton West—were thriving; and the Department of Electrical Engineering was given its own departmental status in the Towne Scientific School. Penn’s international reach was demonstrated by articles on foreign students’ presence on campus and dispatches in the magazine from Penn faculty or alumni in Jerusalem, South America, and China, while other articles highlighted Penn-sponsored charitable efforts—what we’d call service-learning today—in the surrounding community. All of which sounds pretty familiar.

The note of wistful comparison to those more fortunate “sister universities” also has a contemporary ring. A decade later, in 1925, as the University was launching its first fundraising campaign, the Gazette (as we were called by then) editorialized more specifically on Penn’s resource-gap, noting that other schools had already amassed considerable endowments—Harvard, $64 million; Columbia, $48 million; Yale, $40 million—while Penn made do mostly with what it took in from tuition.

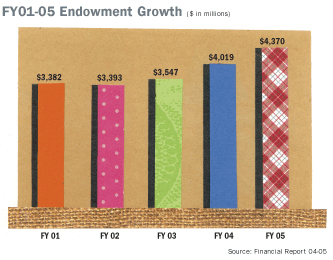

While the University’s endowment has grown in the intervening years to $4.5 billion, Penn continues to lag behind many of its peers. For example, the latest U.S. News & World Report ranking has Penn in fourth place. With the exception of Duke, tied for fifth with Stanford, its companions in the top five are considerably richer: Harvard ($25.5 billion), Princeton ($11.2 billion), Yale ($15.2 billion), Stanford ($12.2 billion).

The gap is even more pronounced when endowment per student is the criterion. According to the most recent figures from the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), Penn’s endowment ranks 12th overall in size, but while Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Stanford remain comfortably within the top 10 schools for endowment per student, Penn plummets to number 71, followed only by Cornell among the Ivies at 73.

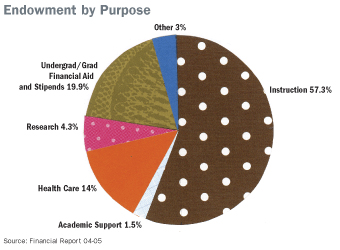

The reason this matters, officials say, is that income from endowment is the engine that fuels new initiatives and bold ventures, and it does so in two ways—first directly, by funding priorities like financial aid and endowed professorships, and then indirectly, by making more revenue available for unrestricted uses by the University.

Financial aid is maybe the clearest case in point. Admission to Penn is “need-blind,” which means that any student qualified to get in is guaranteed a package of grants, loans, and work-study to make attending Penn affordable. In a column in the Gazette last year, Penn President Amy Gutmann called maintaining need-based financial aid “a sacred trust.” However, the great majority of the millions in aid that Penn provides each year comes from the University’s operating budget, while other institutions fund their financial-aid programs largely from endowment income. And the stakes keep getting raised: Several other schools have instituted programs reducing or eliminating loans and increasing grants for students from lower-income families.

Though they have a variety of formulas for deciding how much endowment income to spend annually, Penn and most schools fall somewhere around 4.5 percent; the actual dollars made available are thus a function of the size of the endowment. Given the rate of inflation generally and in higher education, conservative assumptions about long-term average returns, and the need to preserve the value of the funds that make up the endowment, spending more—as wealthy institutions are sometimes called upon to do—is not seen as prudent by decisionmakers.

This imbalance in resources makes the University’s performance over the past decade all the more remarkable, and Penn certainly continues to thrive. Besides the U.S. Newsranking, this fall’s Kaplan-Newsweek Guide to Colleges cited the University among its 25 “hottest schools”—specifically, as the “Hottest for Being Happy to Be There”—and early-decision applications for next year’s freshman class were up by 21 percent.

The University is about to stretch itself once again, with the implementation of President Gutmann’s Penn Compact and its aim to take Penn from “excellence to eminence” by increasing access to a University education, integrating knowledge across disciplines, and engaging locally and globally [“Special Report: Presidential Inauguration,” Nov/Dec 2004]. To support those broad goals, Penn is preparing to embark on a multi-billion dollar fundraising campaign, likely to be announced officially by the end of next year.

Which makes this a good time to take a look at “whence the money” comes from and how Penn makes the most of it.

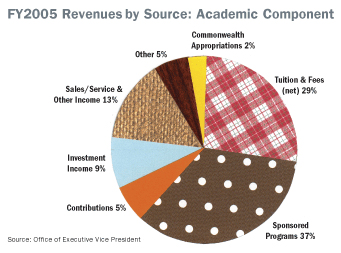

For many purposes, it makes sense to think of the University as a company composed of two principal operating divisions—the health-care component (made up of Penn’s hospitals and physicians’ practices) and the academic component—and to talk about them separately. For fiscal year 2005, which ended last June 30, the University’s total operating revenue was $4.05 billion, divided about equally between the two. (We won’t say much about the health system’s share here—except to share the good news that 2005 was its fifth straight year in the black since the financial crisis of the late 1990s, when deficits ballooned into the hundreds of millions.)

Breaking down the academic component’s FY2005 revenues:

- Sponsored programs, which includes direct and indirect costs of research, contributed about $733 million of the total. By far the largest provider of funding is the National Institutes of Health, with federal funding overall accounting for three quarters of research funds. Penn ranks second nationally in NIH funding, and research support has grown by nearly 9 percent annually over the past decade—though the NIH budget is projected to see much smaller increases in the coming years. New grants were essentially flat in FY2005 at $750 million. Research support from other sources was up, however—foundations up 21.6 percent to $95.5 million, corporations up 5 percent to $45.6 million. The pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, for example, made a second $10 million unrestricted grant to support academic research last year, following up on another gift in 2003.

- Tuition and fees totaled $553 million —after spending on student aid. In FY2005, the University provided $104 million in grants to graduate and professional students and $116 million in undergraduate financial aid. Of the undergraduate amount, $87 million came in the form of grants or scholarships, of which $73 million were from University resources. Grants from endowment income have grown about three times faster than from general funds over the past five years, but the University still funds only 12 percent of its grants from endowment income. (By way of contrast, Princeton, Yale, and Harvard fund about 80 percent or more of financial aid from endowment.)

- Other principal sources of revenue were investment income ($373 million) and contributions ($343 million).

The bulk of expenditures go to fund instruction (40 percent; $767 million) and research (31 percent; $579 million), with the rest distributed among additional educational and other expenses, management, and auxiliary enterprises.

A Penny Saved …

Making all those dollars stretch as far as possible is the job of Penn’s executive vice president, Craig Carnaroli W’85. The University’s chief administrative and financial officer, he manages the areas of finance, public safety, human resources, information systems and computing, audit and compliance, investments, and business services.

The divisions reporting to Carnaroli have garnered a number of external accolades in recent years—as one of the Best Places to Work in IT by Computerworld magazine, and for innovations in electronic commerce, for example—but he takes special pride in a recent citation from Charity Navigator (www.charitynavigator.org), which describes itself as “America’s premier independent charity evaluator.” It gave Penn a score of 67.40 out of a possible 70 in terms of fundraising and operational efficiency.

Savings and cost-avoidance through management efficiencies is one way that Penn competes with its better-endowed peers. “It’s not sexy stuff, it’s blocking and tackling,” says Carnaroli.

For example, to secure lower interest rates Penn has restructured $869 million of the health system and University long term debt of $1.4 billion, for gross savings of $75 million.

Penn also takes advantage of its clout as the city’s largest employer to squeeze deeper discounts from health-care providers and vendors of other services, and uses electronic technology to reduce paper consumption and speed transactions in areas from student services to regulatory compliance.

A number of measures have aimed to control employee-benefits costs, a major concern in an institution where about half of all expenses are people-related. This has included introducing wellness programs, seeking deeper discounts with health providers (like a $1.7 million cut in administrative fees), and performing regular audits of Penn’s retirement population (to ensure eligibility for benefits received) and of payroll to confirm that employees are not getting extra compensation, Carnaroli says. Cost savings related to prescription drug programs for retirees and current employee health-plan participants are projected to save about $15 million annually, for example.

Since FY 1997, the University’s electronic procurement system has generated an estimated $79.6 million in savings, while also reducing the average time it takes to create a purchase order and get it to a supplier from 18 days to less than one. Now used for 70 percent of purchase-order transactions, it recently won an award from the Aberdeen Group for “best practices in e-procurement”—the only award winner from higher education.

(These savings have been gained without compromising Penn’s commitment to buy from West Philadelphia and minority suppliers, Carnaroli emphasizes. In FY2005, Penn spent $70.1 million with West Philadelphia suppliers, and purchased $49.3 million from minority-owned companies.)

Penn has been an early and enthusiastic adopter of various web-based self-service systems for students, faculty and staff. For students, the Penn Portal provides services like course registration and drop/add, dining and housing choices, and financial transactions, while faculty and staff use a site called U@Penn to access benefits information, update personal information, find human resources policies and health and wellness information, and make changes in their benefits. Recruiting and departmental requests to hire new staff are also handled almost entirely online, saving paper and staff time, while speeding the time to fill jobs by about five days.

A system called PennERA (for Electronic Research Administration) has helped reduce the time it takes to establish an account to draw on grant funds by 2-4 days and shortened the protocol approval process from 46 days in 2003 to 22 days. The University is also implementing a new advancement system, called ATLAS, in order to “improve the interface with the alumni community,” says Carnaroli. The system will replace “disparate and aging systems that did not talk well with each other” and improve things like address updating and recordkeeping, as well as coordinate the operations of the treasurer’s office and development and alumni relations with regard to gift information.

The Chronicle of Higher Education recently highlighted Penn’s measures to control energy costs, which save about $5 million annually by closely monitoring usage and taking action—like turning off lights and turning down air-conditioning in the summer—when it rises beyond a certain level. “We have a very successful but unpopular energy-conservation program where we very much try to control peak demand,” which determines rates under the University’s contract with PECO, its energy-provider, Carnaroli says.

Various “strategic outsourcing” initiatives have also added revenues while providing professional service, he adds. These include the Barnes&Noble-managed Penn Book Store, a contract with the food-service giant Aramark to manage Penn’s dining services, and the University City Sheraton and Hilton Inn at Penn hotels. These and other “auxiliary services” accounted for $298 million in FY2005 revenues.

Penn has also partnered with private developers on various construction and renovation projects, limiting the University’s exposure to risk while still encouraging the addition of new retail and residential opportunities in the neighborhood. The first project of this type was the Left Bank at 31st Street between Walnut and Chestnut, in which the one-time GE building was redeveloped into luxury apartments by local developer Carl Dranoff in exchange for a long-term lease on the property. Similar arrangements were used for the new WXPN studios and World Café Live, and for the $71 million retail and high-end residential “Domus” project now under construction by the Houston-based Hanover Company on the former parking lot at 34th and Chestnut streets, as well as another mixed-use development further up Chestnut at 40th Street.

“This came out of a recognition that the University has limited debt capacity, and it needs to preserve it for academic priorities,” says Carnaroli. “So to the degree we are able to do that for some of the support activities that enable the University to grow and be a vibrant place, it’s a very shrewd strategy,” for which he credits Penn’s trustees, former EVP John Fry, and current Vice President for Facilities and Real Estate Omar Blaik.

Agreements of this type might also be a part of plans to redevelop the postal lands east of campus now being acquired by the University, but it’s too early in the process to say for sure, Carnaroli adds.

Another recent partnership is with the computer company Lenovo, which has agreed to offer IBM laptops at a discount to students, faculty, staff—and alumni—through Computer Connection in the Penn Book Store. Any money raised will be directed into financial aid, says Carnaroli.

That’s the end purpose of all the penny-pinching, he adds—to make more funds available to meet the University’s academic priorities. It’s also why endowment funds are so important. Because “so many of the dollars that come into the University are restricted in what they can be used for, unrestricted dollars are the most valuable commodity,” he explains. “So to the degree that you can endow an activity you are able to free up more unrestricted dollars to use for academic purposes.”

An Accelerated Pace

Smart management can only take you so far, and so the University is also looking to increased fundraising and investment returns to maintain and strengthen its competitive position in the years ahead.

The laments that were voiced in 1925 at the start of Penn’s first fundraising campaign still resonate today, says Vice President for Development and Alumni Relations John Zeller, who will be running its next one. “People say, ‘You’re incredibly wealthy,’” given the University’s multi-billion dollar endowment, “yet in terms of its mission and activities, Penn is significantly under-funded.”

As high as they are—$32,364 this year at Penn—tuition and fees don’t come close to covering the cost of education, and can only be raised by so much, while federal, state, and local sources of support and other contractual revenue sources “have been diminished or restricted,” Zeller says. Beyond the percentage of operating budget it accounts for, philanthropy, as one of the “last influenceable revenue streams,” is a “critical, critical component to the success of an institution.”

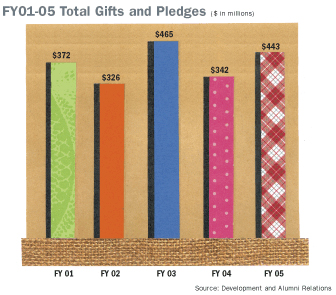

Penn is coming off a very successful year of fundraising in FY2005, raising $443 million in new gifts and pledges and $394 million in cash receipts. Both represent sizable increases over the previous year, and are close to the record amounts posted in FY2003—which, however, included a $100 million contribution from the Annenberg Foundation. There were 83 gifts of $1 million or more, which was a new record, including 33 first-time donors at that level. The number of new scholarship funds established—140—also set a new mark; $32 million went to financial aid, of which $29.4 million was for endowment.

According to a survey by the Council for Aid to Education released in February, Penn’s $394 million in cash was good for fourth place among university fundraising programs. Besides being a source of departmental pride, such rankings send a message externally, says Zeller. “It signals the strength and confidence that its constituency has in the institution. And I think the upward trajectory that development and alumni relations has enjoyed over the last 10 years—and particularly over the last five years—is a very powerful signal.”

During FY2001-2005, gifts and pledges have increased from $372 million annually to $443 million, while cash receipts have grown from $266 million to $394 million. Zeller notes that last year’s totals represent strong showings at both ends of the gift spectrum. There were 127,000 gifts under $100,000, accounting for $111 million, or more than a quarter of the total. “So when somebody says I can only give you $50, or $100, or $500, the importance of that as a cumulative-type of giving level can never be understated,” he adds. Annual giving programs, which generally attract smaller donations, raised $43.3 million last year, up 13.3 percent from FY2004.

The increase in $1 million-plus gifts is a mixture of demographics and the explosion of wealth in the 1990s—half of Penn’s alumni population graduated in the last 20 years. The most successful have accumulated wealth, and “as they begin to be in a position to make gifts, they’re starting to do that,” says Zeller.

Ability to give, of course, is only half the equation. “You look at the continuum of philanthropy and it begins with engagement,” he adds, which is where alumni relations, the Gazette, and other linkages and communications come in. “When people are least able to afford to make contributions is when the institution has to sustain those relationships and continue them,” he says. “A lot of the success we are enjoying today has to do with a lot of hard work over the last 20 years.”

Zeller came to Penn in January 2005 knowing that a major campaign was in the cards—and eager to run it. In his previous post as vice president for development and alumni relations at Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Institutions, he raised more than $1.5 billion over two fundraising campaigns, starting the second the day after the first one ended.

Nearly a billion dollars was raised to support the Agenda for Excellence in 1995-2000, and several Penn schools have had campaigns running in recent years, but this will be the first University-wide effort since the Campaign for Penn, which was the first to break the $1 billion mark when it concluded in 1994. Currently in what is known as the “quiet phase,” Penn’s next campaign—scheduled to be formally announced in late 2007—is likely to seek $3 billion or more, though no official number has been determined yet. “There’s always a pressure to put a very large number on the board,” says Zeller, “but the key to campaigns today is the impact that they can have on the institution and its mission.”

Besides raising the sights of donors in terms of what they might consider as a gift—“it’s a unique, creative time in the history of the institution”—campaigns also create a heightened institutional focus. “What’s important? What is it that you want to say? Where do we want to be at the end of seven years that we aren’t today? What is the impact?” says Zeller. They also engage people in a variety of ways, creating a rallying point for donors, volunteers, other alumni, and staff. “There’s an accelerated pace to everything you do.”

“Perfect Storms” & Long Term Views

Penn’s five-year return on investments places it within the top tier of endowments over $1 billion, but that didn’t stop the editors of The Daily Pennsylvanian from headlining their editorial on the endowment’s FY2005 performance “Endowment Stagflation” and complaining that “Penn’s overly conservative investment strategy is crippling.”

Penn posted a return of 8.5 percent for the year. That was slightly below the 8.7 percent return of its composite benchmark (made up of indices in a variety of asset classes weighted proportionally to Penn’s holdings) and a bit better than the S&P 500 return of 6.2 percent. But it fell short of the average for all higher-education endowments and was well below the performance of most other $1 billion-plus endowments.

According to NACUBO’s annual survey of higher-education endowments, the average change (which includes gifts as well as return on investments) in endowment value for FY2005 was 9.3 percent. For endowments over $1 billion, the figure was 13.8 percent, attributed to their greater diversification and exposure to alternative investments. Penn’s percent change in endowment was put at 8.7 percent. That was last in the Ivy League, with other schools scoring double-digit results ranging from 10.6 percent (Dartmouth) to 19.4 percent (Yale).

None of this came as a surprise to Chief Investment Officer Kristin Gilbertson, who calls last year “a perfect storm” in which “everything that Penn didn’t have did spectacularly well.”

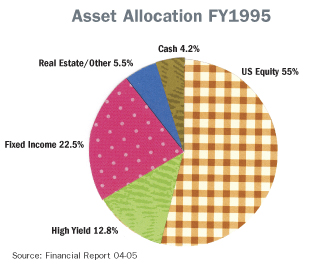

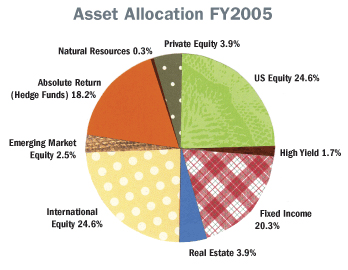

Gilbertson—who had previously managed public equities for Stanford’s management company and before that was a principal investment officer and strategist at the World Bank—was appointed CIO in the summer of 2004, just as the fiscal year was beginning. “Based upon what I knew of Stanford’s portfolios and all the other portfolios and the preliminary returns that I’d seen,” it was clear that Penn would suffer, she says. “We all knew that we were differently positioned than other universities because we did not have private equity. We did not have as much real estate. We had no emerging markets when I arrived here. We had much more U.S. public equity and much more U.S. fixed income than our peers, and we had very little natural resources or commodities.”

The reason for this goes back to decisions made five and 10 years ago, says Gilbertson, which is when many of the investments reaping benefits now were initiated. One prominent example of that would be the money several institutions put into an obscure Internet search engine called Google through venture capital firms back in the late 1990s, which contributed mightily to last year’s gains—especially Stanford’s stunning 23 percent rise in endowment. More generally, investments in assets like real estate and natural resources, typically done through limited partnerships, can take years to mature.

Penn was just then in the midst of setting up its office of investments in its current form, after two decades during which its portfolio had been run—for the most part, with spectacular success—by emeritus trustee John Neff Hon’84 [“An Eye for Value,” March 1998]. Neff stepped in when the University was in real trouble, after a series of missteps had left Penn’s among the worst performing endowments of the 1970s. Under his stewardship, the endowment grew from $200 million at the end of 1979 to $2.5 billion at the end of FY1997. But Neff was leery of the stock market’s apparently unending rise in the late 1990s. The University largely missed out on the tech boom and was slow, compared to its peers, to diversify out of U.S. equities and fixed income into the alternative investment categories that have outperformed in recent years.

“We have been a little bit more conservative than some of our peers,” says Gilbertson. “This office has only been in existence for eight years. David Swenson has been at Yale for more than 20 years now. Jack Meyer was at Harvard for 15 years,” she adds, citing two of the most successful—and controversial—endowment managers of recent years.

Harvard has come under fire for the compensation paid its managers, which contributed to Meyer’s departure to start his own firm last year. Gilbertson, a Harvard alumna, notes that “Harvard runs differently than we—and every other endowment—do, because they are actively investing dollars” rather than hiring outside managers. “To keep people on that level after they’ve learned on your dime is really critical,” she says. “What those guys are earning at Harvard is a lot of money—it’s a lot more than I’m getting paid—but it’s a fraction of what a good hedge-fund manager can make when they’re shooting the lights out.” (For the record, though the University won’t disclose salaries, no one working in the investment office is among Penn’s top five highest-paid employees.)

At Yale, the criticism of Swenson has focused on claims of excessive secrecy regarding the university’s investments, but Gilbertson insists that there is a “strategic need” for secrecy. “We put a lot of time and dollars into finding these ideas. Endowments are in competition, and the last thing you want is to be talking about your World’s Greatest Idea and then have [someone else] go do it,” she says. “I’d hate to give up our trade secrets to other people, because there’s only so much capacity in great ideas, and they tend to go away when they get bid up with other capital going in.”

As CIO at Penn, Gilbertson works with a subcommittee of Penn trustees headed by Howard Marks W’67, chair of Oaktree Capital Management, to develop the office’s “strategic asset allocation,” which defines in broad terms how the University’s resources ought to be distributed among different investment classes. They also look for opportunities that merit deviating from those targets—what Gilbertson calls a “tactical asset allocation.” For example, the University was “overweight” in international equities in FY2005. Those investments, particularly in Japan, performed exceptionally well, helping bolster returns. With those decisions made, the final step is manager selection—“finding smart people to be invested with,” she says.

Endowment funds, which are seen as long-term investors—“smart money”—are generally valued over private investors or other institutional investors such as pension funds. In Penn’s case, there is also the advantage of the University’s extensive alumni network in the financial world. “Some of these investment vehicles are very small-market, and there are a couple of phenomenal investors that everyone wants to be invested with,” she explains. “They can only let so much money in the door and being Penn really helps in these circumstances.”

Since arriving at Penn, Gilbertson has been developing a staff with expertise in key market areas such as real estate and natural resources, private equities, hedge funds, public equities and fixed-income, and emerging markets. “Endowment performance is critical to the financial health of the University and to its academic programs, and because of that more and more universities are setting up endowments and managing them professionally,” she says. “This turnover in the endowment world has given me the opportunity to approach a couple of great people and bring them to Penn.

“I can come up with two or three or four great investment ideas a year. But you need a team of people doing that,” she adds. “And I think that we’re really getting some great people here to help on that.”

Gilbertson estimates that it will take three to five years to build up Penn’s portfolio in alternative asset categories like private equity, real estate, and natural resources. Rushing that process “would be an enormous mistake,” she says. “Evaluations are very challenging right now across all asset classes. There ain’t a whole lot up there that’s cheap.”

Simply matching Stanford’s or another high-performing endowment’s investment in real estate, for instance, would “be insanity because we’d be paying top dollar for those assets,” she says. “Best to wait for a little distress and we’ll get our opportunity.”

Looked at over the past five years, she says, Penn’s measured approach to remaking its portfolio paid off. Over five years, the endowment had an annualized return of 7 percent; the three-year return was 9.9 percent. The five-year return puts Penn among the top 10 performers among endowments over $1 billion.

“Penn looked bad in 1999 and 2000 because we had this enormous value tilt in U.S. equities, but we hung in to that value tilt when it was very painful, very difficult, and that was why Penn outperformed in 2001 and 2002,” she says. The University had positive returns in June 2001, “when the tech bubble was really starting to burst,” and in June 2002, “the summer when the S&P hit its low point,” when many other endowments saw negative returns (-3.6% in 2001 and -6% in 2002, on average).

While the University’s portfolio will look more like its peers, that’s for the sake of diversification—doing a better job of spreading the risk—and not to chase past returns. “We don’t today have the buyout portfolio that Stanford does or that Yale does. But we will be there. We’re gearing up to get that,” Gilbertson says. “But quite honestly, are buyouts or real estate really going to be the engine that drives performance in fiscal year 2007? I don’t think so.” While the lack of private-equity investments hurt Penn last year, “there are going to be years and years to come where people are going to pay for having a lot of private equity,” she adds. “You want to have different bets working for you. You need to have a couple of balls in the air.”

A Positive Trajectory

As the University passed the half-way point in the current fiscal year, the three administrators were looking forward with, well, “bright anticipation.”

“We’re doing very well. I think we’re on a very positive trajectory,” says Zeller. “People are focused on what the institution’s needs are, and I think, in preparation for the public launching of this campaign, we’re beginning to see a lot of resonance with it and people are starting to support it.”

Through the end of December 2005, giving totals were on a pace to exceed last fiscal year’s performance. At $228,443,676, gifts and pledges were ahead of last year’s results at the half-year mark by about $12 million; while cash receipts were up by about $32 million at $234,772,455.

Gilbertson is still “pinch hitting” on public equities and fixed income, but otherwise her management team is fully staffed. Led by strong international returns, results for the calendar year 2005 were trending positively. More important for the long term, though, “We’re planting seeds for the future,” she says. “We are finding select opportunities,” she adds, referring—obliquely—to Japanese equities and German real estate. “There are some other things out there that are cheap—and I’m not going to tell you what they are.”

After declaring himself “bullish,” Carnaroli takes a prudent step back, noting various causes for caution and concern: “Energy costs are hitting us hard, and security costs, and we’re seeing people feel the pinch in the strains of the economy—some of the inflationary pressures—that we are going to have to address in a proactive way.”

Still, he says, he sees “a lot of good things coming.”