In much of her own work, the poet Marilyn Nelson channels African-American history. As the founder of Soul Mountain Retreat, an artists’ colony in rural Connecticut, she is nurturing the next generation of writers.

By Meredith Broussard | Photography by Don Hamerman

Sidebar | A Mentor to Many

For a writer who craves both quiet isolation and stimulating company, Marilyn Nelson G’70 may have the ideal living arrangement. The former poet laureate of Connecticut and University of Connecticut emeritus professor of English spends much of her time in rural solitude in a sprawling old nine-bedroom house in the middle of a nature preserve in East Haddam near the unspoiled Eightmile River. But Nelson’s house is also the home of Soul Mountain, an artists’ retreat she founded in 2003 after retiring from teaching. In addition to her living quarters—dubbed “Lady Marilyn’s wing”—there is space for four writers at a time to, in the words of the retreat’s website, “enjoy contemplative writing time, the respectful companionship of peers and mentors, and the inspiration of the natural surroundings in a diverse and intimate community that honors the freedom and the responsibility of the creative act.”

Many people imagine that the writerly life is just about walking down to the river and contemplating. “It can be, if you’re willing to just live for yourself,” says Nelson. “I made a decision to try to live with a larger commitment. It’s like deciding to have three children instead of two—it requires a lot more of everything.”

Nelson’s voice is high and gentle, and she wears her narrow dreadlocks pulled neatly back from her face. “Enchanting” is the word the poet Daniel Hoffman uses to describe her demeanor. Now an emeritus professor of English at Penn, he taught Nelson as a graduate student and was an early champion of her work (see box on p.51).

That work includes books of poetry, poems for children, and translations, and it has garnered a slew of awards over the years. Her collection of biographical poems about George Washington Carver, Carver: A Life in Poems, won the 2001 Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for excellence in children’s literature as well as the Flora Stieglitz Straus Award. It was also a Newbery and a Coretta Scott King honor book. Her poetic memoir, The Homeplace, which came out in 1990, won an Anisfield-Wolf Award for books that contribute to understanding racism and appreciating cultural diversity, while 1997’s The Fields of Praise: New and Selected Poems won the Poets’ Prize, given annually by a committee of about 20 American poets who serve as judges and also contribute the prize money. All three volumes were also named as finalists for the National Book Award. Other honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, two awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Fulbright teaching fellowship, a pair of Pushcart Prizes (honoring the best small-press publications), and the 1990 Connecticut Arts Award. Her term as poet laureate of Connecticut ran from 2001 to 2006. Besides serving on the UConn faculty from 1978 to 2003, Nelson also taught summers at the MFA program at Vermont College and at Cave Canem (a nonprofit organization dedicated to the “discovery and cultivation of new voices in African-American poetry”), while raising two, now adult, children.

For her most recent book, 2007’s Miss Crandall’s School for Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color, Nelson collaborated with poet Elizabeth Alexander Gr’92, professor of African-American studies at Yale University, whose collection American Sublime was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2005. The book consists of 24 sonnets in the voices of the young women who attended the school that Prudence Crandall ran in Canterbury, Connecticut, from 1831 to 1834. Miss Crandall, a Quaker, began the school as a boarding school for white girls in 1831, but after blacks were admitted she faced harsh opposition from the community. In addition to suffering various acts of vandalism against the school, Crandall was arrested and faced three trials for breaking a law passed specifically to prevent her operating the school for black students. Though the case was ultimately dismissed, a mob attacked the school in September 1834, forcing its closure. The building is now the site of the Prudence Crandall Museum.

In the book, Alexander and Nelson inhabit the personae of the different girls, showing a breathtaking range of personalities. Consider the words of this feisty young woman, Miss Ann Eliza Hammond, from Nelson’s poem of the same name:

I ain’t payin’, and I’m stayin’. People’s dreams brought me

to this school.

I’m their future, in a magic looking-glass.

That judge and the councilmen can kiss my rusty black.

In these few lines, the reader can see Hammond’s determination, doggedness, and desperation to achieve. Nelson imagines one girl’s perspective on a historic struggle in a way that illuminates the struggle faced by an entire community.

A historical perspective also animates The Homeplace, although here Nelson’s own past is the focus. She explores her family’s identity and tangled history, starting with Diverne, her great-great grandmother, who was brought to the United States from Jamaica unwillingly. Diverne was enslaved on a plantation in the American South and bore a child to the plantation owner’s son. “I started writing the book as a way of writing out my mourning for my mother, and as a way of making a kind of posthumous tribute to my mother and to her family,” Nelson says. “I can’t explain why, but it came out as poems. After a while, I realized that what I was doing was writing a public book, an explanation of the source of a black family’s pride in its roots.”

Nelson’s immediate roots trace to Ohio, where she was born in 1946 to Melvin and Johnnie Nelson. Melvin was in the military, a member of the renowned Tuskegee Airmen, and Johnnie was a teacher. The family moved around as her father was assigned to different military posts during Marilyn’s childhood. She wrote her first poem at age 11, and was known in her family as a dreamer. She graduated high school in California, and then went on to the University of California, Davis before coming to Penn for graduate school in 1968 to study English.

Nelson’s time at Penn wasn’t exactly idyllic. “My boyfriend was in Venezuela, I was 3,000 miles from home, I lived in a rooming house,” Nelson recalls. “Everywhere, it felt like revolution was around the corner. I was so very poor. I’d go to the grocery store and stand there, looking at all of the food, and have fantasies about stealing steaks.” For months, Nelson waited for a check to arrive from the Veterans Administration, which was helping to pay for her education because of her father’s service. Finally, she discovered that an administrator at the VA had forgotten to send in all of the students’ funding paperwork.

At the same time, Nelson formed some important artistic and personal relationships at Penn. She studied with the late Robert Lucid, then professor of English, and took an American Literature class with Dan Hoffman, who became her mentor.

“Knowing that I’d published poems, Marilyn shyly asked if she could show me hers,” Hoffman recalls. At the time, he was compiling student work for a collection published as New Poems 1970 and chose a poem of hers to include. “It was always a special pleasure to find a student who was talented and dedicated to writing poetry, so I enjoyed getting to know Marilyn in this way,” he says.

“That relationship with Daniel Hoffman is worth every day I stood in the grocery store fantasizing about stealing food,” Nelson declares. In fact, it was Hoffman’s encouragement that helped get her back into writing poetry after a long fallow period. For several years after she left Penn with a master’s degree in 1970, distracted by personal issues and occupied with childrearing, Nelson did not write an original poem. When she did, she sent it to her former professor. Hoffman wrote back immediately, urging her to send him more of her work.

“I read her work eagerly and was really struck,” says Hoffman. “This was a time—in the seventies—when most poets of color, except for their elders like Sterling Brown and Robert Hayden, were in the grip of an aesthetic of rage and protest, poetry as propaganda. Another feature of the zeitgeist was another sort of protest: angry feminists demanding that gender wrongs be righted immediately. Marilyn’s poems were different.”

Once Nelson began writing again, there was no stopping. She grouped her poems together into a manuscript, which Hoffman read and recommended to his publisher, Louisiana State University Press. “What do we ask of a new poet but that she compel us to share the breadth of her experience, the depth of her feelings?” he wrote to the press. “Marilyn [Nelson’s] poems reach past feminist anguish and black rage; they spring from her own sources in an accomplished style that is at once lean, subtle, and strong. A first book to be welcomed.”

Nelson published For the Body, the first of her many books, in 1978, and the following year earned her doctorate from the University of Minnesota. Next came two collections of children’s poems written with Pamela Espeland: Hundreds of Hens and Other Poems for Children, a translation from Danish of poems by Halfdan Rasmussen, in 1982; and 1984’s The Cat Walked Through the Casserole and Other Poems for Children, an original collection inspired by things the authors found amusing about their own early years.

During this time Nelson was also raising a son and daughter. She explored the theme of motherhood—and femaleness—in her 1997 collection, The Fields of Praise: New and Selected Poems. In addition, poems like “The Life of a Saint,” “Psalm,” “I Dream the Book of Jonah,” and “Letter to a Benedictine Monk” addressed spiritual themes, while her historical roots were the focus of the book’s second section, a series of poems that dealt with the Tuskegee Airmen.

As Nelson’s friend and fellow poet Marilyn Hacker wrote: “[Her] airmen, though, are individuated in a different (and indeed more familial) way, in narratives and dramatic monologues (wrought from informal interviews) counterpointing the daily routines, triumphs and losses of men at war with the incontrovertible weight of race in their lives, from the ‘full-bird colonel’ mistaken for a porter in an airport to the squadron of black officers imprisoned for refusing to sign an agreement not to enter the officers’ club—while German POWs smoked and laughed outdoors.”

In an appreciation of Nelson’s work published in the Women’s Review of Books,Hacker detailed how Nelson’s poems explore all aspects of the ordinary and the extraordinary life. Her work deals with the love and loathing that a young mother has for her children; it deals with the trauma faced by Tuskegee Airmen asked to give up their lives for their country, yet punished by irrational segregation and Jim Crow policies; it deals with the quotidian and the sublime.

Nelson’s later work builds on these same themes, with a wider range of characters. In Carver: A Life in Poems, a series of sonnets creates a biographical portrait of scientist and inventor George Washington Carver. The book takes the reader through Carver’s early years in slavery, his education, and his years of prodigious research and educational efforts. In today’s parlance, Carver could be called a pioneer of environmentally friendly and “green” manufacturing practices. In his most famous research, he discovered or developed some 325 peanut-derived products, from an “evaporated peanut beverage” to baby-massage cream to a substitute for rubber; other inventions include a process for making paint and stain from soybeans, 75 products derived from pecans, and 108 new ways to use the sweet potato.

“She’s really a pioneer among African-American poets in writing to a young adult audience,” says Penn English professor and fellow poet Herman Beavers, another admirer of Nelson’s work.

“No one is more technically gifted” than Nelson, he says. “In Carver, the poems are just as challenging, technically complex, and well-crafted as ever—they’re just written to a young adult audience,” Beavers adds. “She really recovers George Washington Carver in all of his complexity and brilliance in ways no history or biography has done. The history is magnificent—and then you realize you’re reading poems.”

“Like many, I fell in love with George Washington Carver as a child. I thought that I’d be a scientist,” says Nelson. She wasn’t planning to write about Carver when she began the biography project; in fact, she was researching and planning to write a saint’s life about St. Hildegard of Bingham when a friend brought up Carver in conversation. “It came out of nowhere! I realized he was the saint I wanted to write about.”

In the course of her research, interviews, and thinking about Carver, Nelson developed what she calls “a real romantic respect” for him. “I had a picture of the young Carver over my desk while I was writing—he was smart, he was delightful, and he was so handsome,” she says. “I sometimes looked at him and said, ‘Professor Carver, it is a shame I wasn’t around when you were—we could have been something together!’” Knowing of her affection for Carver, Nelson’s assistant dubbed the pond in front of Soul Mountain Retreat “Peanut Pond.”

Nelson describes Soul Mountain’s beginning as “a seed of a dream, kept in the back of my mind for seven years.” She imagined a “space to which I could invite young poets to have a quiet place to write,” she says, and at first considered building an addition to her family house, but that proved impractical. “So I began looking, and I found this property: a humongous nine-bedroom house that was originally built as a family’s summer house,” she says. “I just took a leap of faith and sunk everything I had into this big house in the country.”

In the years since Nelson established Soul Mountain as a nonprofit foundation in 2003, following her retirement from teaching, her leap of faith has succeeded. With the support of the University of Connecticut and individual donors, the retreat now offers three residency cycles each year for about four writers at a time. Both established and emerging poets have sought out Soul Mountain’s particular blend of space, time, solitude and beauty. Residencies are available during spring, summer, and fall. If a writer’s application is accepted, he may stay for as little as a few days or up to four weeks, sharing cooking and everyday life with a community of other writers.

Many Soul Mountain residents perform their work at the nearby Florence Griswold Museum, which hosts readings and receptions for visiting artists. “They’re happy to collaborate with us because we’re doing exactly what Florence Griswold herself did, years ago,” says Nelson.

From 1899 until her death in 1937, Griswold, a former resident of nearby Old Lyme, Connecticut, turned her family mansion into a boardinghouse for artists, primarily American Impressionists, who sought rural solitude in which to create art. Griswold’s artists’ colony, known as the Lyme Art Colony, was the epicenter of American Impressionism in the first decades of the 20th century. Its famous visitors included landscape painters Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and Henry Ward Ranger.

Last year Nelson participated in an exhibit at Griswold’s mansion-turned-museum that combined her poems with pictures from the museum’s collection in a meditation on history, culture, landscape, and art. The Freedom Business: Connecticut Landscapes Through the Eyes of Venture Smith featured poems by Nelson inspired by the life of Venture Smith (c. 1729-1805), an African-American landscape painter and businessman. Smith, a former slave, purchased his freedom and that of his family.

To create the poems, Nelson browsed through the museum’s collection and chose landscapes that connected with aspects of Smith’s autobiography, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa but Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America, Related by Himself, which he dictated to a schoolteacher in 1798. The narrative covers Smith’s childhood in Africa, the horrors of the Middle Passage, his long years in slavery, and the prejudice that he battled while becoming a successful businessman, the owner of 20 boats and 100 acres along the Connecticut River. Nelson chose some paintings that suggested specific incidents in the book: a couple on the riverbank who might be conspiring to escape, or a farmhouse with a red glow beaming out of its window, suggesting a burning whip. She chose other landscapes, like a snowy bend in a country road and an image of lush, orderly farm fields, for their allusions to places in the story, and others, representing different seasons, to give the viewer a sense that time was passing.

In the exhibit, 14 of Nelson’s poems hung next to 13 landscapes from the museum’s collection. The pairs were arranged in chronological order according to the events recounted in Smith’s autobiography between 1751 and about 1790, when he was able to purchase freedom for himself and his son and daughter. A book version is scheduled to appear in October.

The Connecticut River was a great part of Venture Smith’s success, and the nearby Eightmile River plays a similarly important role in Marilyn Nelson’s life as a spot for contemplation, meditation, or inspiration. To get to the river, Nelson walks down a paved path, a third of a mile long, wide enough for only a single car. Sometimes, her destination is a picnic table on the riverbank, a table she placed there shortly after she bought the property and turned it into Soul Mountain. Many visitors remember it as a favorite spot for thinking, she says.

On a recent stroll to the river, as Nelson tells it, she saw a fox cross the path in front of her as she made her way past the flowering dogwood trees to the picnic table on the banks of the river. The fox trotted from the riverbank to the meadow, oblivious to Nelson, who stood still a few feet away. The fox ambled into the underbrush. Stopping suddenly, it turned to contemplate Nelson. Then, the fox leapt in the air to get a better look. Surprised, they stared at each other for a moment, the quick brown fox and the casually dressed poet.

The fox had the right idea. Marilyn Nelson is the kind of remarkable person, and the kind of remarkable poet, who demands a double-take.

Meredith Broussard is the editor of an anthology, The Encyclopedia of Exes. Her website is www.failedrelationships.com.

SIDEBAR

A Mentor to Many

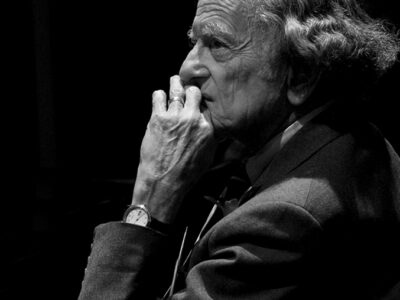

Poets Daniel Hoffman, emeritus professor of English, and Marilyn Nelson G’70 were both new to the University when they met in 1968. She was a graduate student working on her master’s in English and an aspiring writer, and only the year before Hoffman—whose first book, An Armada of Thirty Whales, won the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1954—had led the first creative writing seminar at the University. Although she didn’t take that class with him, Nelson would be among the first of dozens of students Hoffman would mentor in the succeeding decades, while cementing his own reputation as a major poet with works like The Center of Attention, Brotherly Love, Hang-Gliding from Helicon: New and Selected Poems, 1948-1988, and Middens of the Tribe.

“For 26 years, I had the great good fortune to meet every week with some of the most talented young people in the country,” Hoffman reflected last spring, following an Alumni Weekend event at Kelly Writers House at which some former students read their work and Hoffman presented poems by his late wife, Elizabeth McFarland Hoffman.

Hoffman taught the seminars from 1967 to 1993. Initially they were limited to undergraduates, but after a few years he persuaded the English department to let him add a graduate course as well. Students had to apply to be in the seminars, and Hoffman recalled that he always asked one question in interviews to help him make his selection: Which poets do you read for pleasure?

“If the answer was, ‘Oh, I don’t really read poems,’ or, ‘I want to be original so I don’t read other poets,’ I permitted those wannabes to write their verbal spaghetti elsewhere,” he said. “Those who loved poetry, had tried to write it, and had some facility with the language, were soon seated around my table every Thursday at 2 p.m.”

Some 30 of those students have sent Hoffman copies of their published work over the years, and they represent “an amazing roster of excellence,” he said: Two MacArthur fellows; the director of the Guggenheim Foundation; and winners of the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the New Criterion Poetry Prize, and a host of first-book, translation, and other poetry prizes. (See our website, www.upenn.edu/gazette, for a list of former students and their works.)

“A writing teacher can’t claim credit for his students’ talent—they come with that,” Hoffman added, “but he can give them encouragement and guidance, introduce them to the resources and the history of their art and of our language, show them the ways that form and diction and sound and rhythm and the appearance on the page all contribute to a poem’s success.

“I’m proud that none of my former students tried to imitate me,” he said. “A teacher should help his young acolytes find their own voices, in which, when they have had more experience of life, they will express their individuality.

“I’m sure that Penn’s recent and current students will prove, as the years pass, as gifted and original as those from my time at Penn. I look forward to reading their work.”

—M.B.