Taking his first live snap in the NFL, a rookie field-goal kicker—who also happens to be a 43-year-old sportswriter—learns about pressure.

By Stefan Fatsis | Illustration by Jay Bevenour

Sidebar | Q&A with Stefan Fatsis

During the Denver Broncos’ team camp and minicamp, I felt like I was trespassing. On the field, I didn’t want to steal time from the kickers fighting for a chance. Off the field, I didn’t want to attract any more attention than my presence already did. In 25 years of reporting, I’d never felt so tentative. An NFL locker room, not surprisingly, is an intimidating place.

Time, though, is a good relaxant. Nervousness about my ability and my physique—showering next to my huge, sculpted teammates instantly destroyed the pride I’d taken in my dozen pounds of new muscle—is fading. My presence is no longer noteworthy. Journalistically, this is terrific. The players don’t care anymore that I’m carrying a notebook, and when they remind themselves that I am they keep talking anyway. And they seem to respect that, no matter my skills, I have the guts to be here at all. “You’re doing this stuff,” Amon Gordon, a sensitive, soft-spoken 312-pound defensive tackle, tells me one day. “You’re doing it.” Still, I want to be accepted not just as a teammate but as a player.

Most of the Broncos rarely watch me kick. If they wander out early and witness only one of my inevitable pop-ups or line drives, that kick defines me. That’s a performance issue. Then there’s a confidence issue. I fear failure and its attendant embarrassment, which argues deeply against attempting what I’m attempting. It’s one thing to try, in early middle age, to become an expert Scrabble player. It’s another altogether to try to become a professional athlete.

The fifth day of training camp is the first to include “FG/FG Rush” on the schedule: field-goal practice, with a live rush from the defense. In the training room, I rub Flexall, a mentholated aloe vera gel, on my quadriceps, hamstrings, and groin (a little too close to the private parts), and I slather my neck and face with sunscreen. A training staff summer hire stretches my legs. To make the environment I might encounter feel familiar, I close my eyes and visualize the full assemblage of Broncos watching me kick, the thousand fans gathered on the berm by the far sideline, my technique. I imagine good plants and solid hits—the kicking mantra I’d developed with a sports psychologist.

Still, I don’t think Broncos head coach Mike Shanahan will let me kick with the team. It’s too early in camp. The starting field-goal kicker, Jason Elam, hasn’t even kicked yet. Special teams coach Ronnie Bradford won’t give me a straight answer on whether I will. We have 40 minutes before FG. We stretch, punt, loosen up. I ask Jason the plan.

“We’re going to kick field goals,” he replies. “The idea is to kick the ball between the tall yellow things.”

Jason will kick 10 balls, two apiece with the ball on the 10-, 15-, 20-, 25-, and 30-yard lines, or field goals of 28, 33, 38, 43, and 48 yards. With 20 minutes to go, I pace back and forth on an adjacent fake-turf field where we kickers practice. I need to pee. Inside a Port-O-Let, I hear fans talking about me.

“He hit four in a row the other day,” one says.

“But they were 10 yards out and didn’t get 10 feet off the ground,” another replies.

Everybody’s a critic. I jog back and kick a dozen balls from 25, 30, and 35 yards. Good plant, solid hit. When I connect from 35, Ronnie says, “That’s going to be your distance.” This isn’t casual stand-around-and-schmooze kicker talk. Ronnie is dead serious. Under the lights. Bullets flying. If Shanahan summons me, Ronnie is saying, I’ll be kicking from 35 yards.

“One kick?” I ask.

“One kick.”

I have to pee again. Two more fans are standing near the sideline of the kickers’ field.

“Jason was kicking from here,” one says.

“Number nine’s pretty good, too,” the other says before I trot by. “Way to go, nine!” he says.

I scoop up the orange duffels and my fellow kickers Paul Ernster and Micah Knorr—who are competing for the team’s punting job—and I migrate to the empty grass field next to where the rest of the team is practicing. Paul snaps and Micah holds. From 40 yards, I strike with foot sideways, skip through directly toward the goalposts, and land with my toe pointing straight ahead. Perfect execution. ‘‘Way to go, dog!” a fan screams. But I’m growing visibly nervous. I ask Paul to hold my Broncos cap and my notebook. “Relax, dude,” he says. “Just do what you do. You make a hundred out of a hundred if you do what you do. No sense making it harder on yourself.”

I nod. I’m hungry. Inside my helmet, I feel perspiration form beneath my forehead and burst through the skin. We walk to the sideline. General manager Ted Sundquist mimics John Facenda’s voice-of-God baritone from the classic NFL highlight reels: “The hot breath of the defensive end. The beads of sweat pouring down his cheek …”

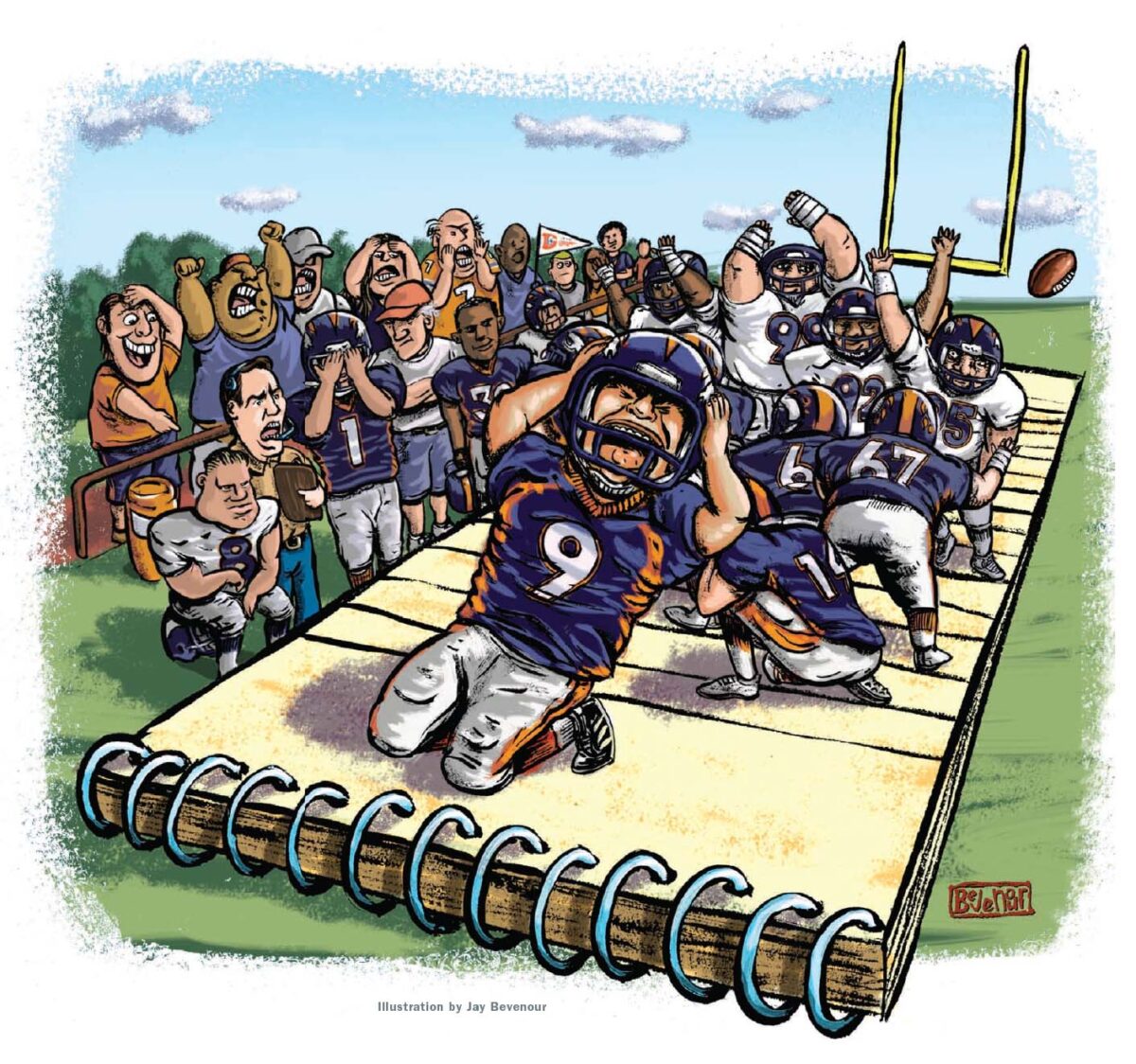

The airhorn sounds: FG. I jog onto the field with Jason for our first moment in the spotlight. Shanahan shoos me off. While Jason kicks, I stand a couple of yards in front of the team, shaking out my right leg, pacing, breathing the way sports psychologist David McDuff recommended to relax and focus: in through the nose for four counts, hold for seven counts, out through the mouth for eight counts. It’s supposed to release tension. But it’s not working. The players are watching. The coaches are watching. The fans are watching. This scene doesn’t feel familiar at all. A few days earlier, Jason had described the kicker’s job as “hours and hours of boredom surrounded by a few seconds of panic.” My few seconds feel like a lifetime.

Each of Jason’s kicks is a tracer bullet that soars through the goal posts and smacks into or passes through the hydraulic video tower scaffolding beyond the end zone. I try another breathing technique, one used when the body’s physiology kicks into overdrive: hyperventilating through the nose to tighten the muscles, then taking some clearing breaths to release the tension. I want to look like I’m preparing to kick. Instead I look like I’m having a nervous breakdown. Paul writes in my notebook: “Pacing rapidly, rigid, frantically breathing, looks like a man awaiting execution. Elam is drilling field goals effortlessly. More pressure on SF.”

Then the horn sounds to signal the end of field goal, and I suddenly realize I’m not going to kick. I’m deflated that Shanahan has left me out—this is why I’ve come to Denver—but also relieved. My mind had been invaded by an army of tiny, hectoring kickers. Smooth steps back! Stay down! Be aggressive! Good plant! Bend over! Chippin’ and skippin’! Head down! Leg to butt! Hips open wide! Foot perpendicular to ball! Solid hit! Follow through toward the goalposts! I couldn’t have made a 35 yarder if you had spotted me the first 25. Having experienced the prekick stress, I think, will help me when I actually do have to kick. Phew.

Shanahan motions the team to the middle of the field before the next drill. “In this business,” he says, “there’s a lot of pressure, and a lot pressure put on kickers. We’re going to put some pressure on our kicker, Stefan. He’s going to kick. If he makes it, meetings will end at nine instead of nine thirty.”

A war whoop rises from the team. As I record Shanahan’s words, defensive back Nick Ferguson snatches my notebook. “Quit writing!” he shouts. The special teams line up on the 12-yard line—a 30-yard field goal—and the fans realize what’s happening, Applause builds. “Come on, nine!” “Let’s go, nine!” “Come on, Fatsis!” Jason approaches. “Stefan, you know there’s a 25-second clock,” he says with a grin. I’m too frightened to ask whether he’s joking.

In the movies of our lives, the most meaningful moments occur in slow motion. We want to preserve them and relive them, find a way to recover the most evanescent details: the first upturn in a smile, the bounce of a bob of hair, the instant when two pairs of eyes meet, the flutter in a skirt. We want to savor the experience. We want to enjoy. Intellectually, I recognize that this should be one of those moments. I am comfortable with my teammates now, and comfortable in front of crowds. I have spoken to audiences in the hundreds, appeared dozens of times on national television, talked to millions of people on the radio, had my work critiqued in the pages of influential newspapers and magazines. I am comfortable with spotlights. I couldn’t have conceived, arranged, and carried out this extended performance with an NFL team if I wasn’t.

In sports, there is nothing quite so appealing as the split second before execution. There’s the anticipation of what will happen, for sure, but also the exquisite beauty of the pause: the moment of nothingness before the explosion of everythingness. But instead of soaking in the attention, in appreciating the most unlikely moment of nothingness in my life, I am totally freaking out. I can’t find a way to slow things down. I can’t smile. I can’t high-five the other players and skip into place. I can’t acknowledge the fans with a rock-’n’-roll finger point, the way punter Todd Sauerbrun does. I can’t pat my long snapper, Mike Leach, on the ass and my holder, Micah, on the helmet. I can’t call the field-goal team together for an impromptu huddle and a self-effacing joke. I can’t see anything around me—but I can’t shut out the fact that I’m surrounded, either. Nothing looks clear. It’s as if I’m standing a few inches from an impressionist painting, the players, the Broncos staff, the fans on the berm all dissolving in a pointillistic blur. I want to fast-forward to tomorrow. I want to disappear.

Suddenly, the offensive line is bending over. I tap the ground with my right foot and take three erratic steps back and two over. I don’t take a practice swing. I exhale hard. My body is shaking, my fingers twitching. I never come to a complete stop. Rather than nodding my head at Micah to signal that I’m ready for him to call for the ball, I say, inexplicably, “Go!” Go? Go? What was that? Then the ball is snapped and I’m racing forward. Left, right, left—I feel my plant foot slip and my body falling backward. I kick the grass first and then the ball. There is no explosive sound, no sound at all, really, no power. No chance. I hear shouts of “Get up, get up, get up!!!” and then “No, no, no!’!” And a crescendo and decrescendo wave of “Awwwwwwww!!!” as the ball shoots under the crossbar.

I grab my helmet with both hands, turn my back to the goalposts, and collapse into a question mark. A chorus of laughter surrounds me. When I lift my head, I see Nick Ferguson leaping up and down and shouting. “Offside! Offside!” He helps me up. “Five-yard penalty!” Shanahan says. “Offside! Do it again!”

“No, no, no!” I shout to Shanahan. I don’t want to go five yards closer! I can make a 30-yarder! But no one listens. Wide receiver Rod Smith cradles my helmet and whispers encouragement in an earhole. The crowd starts clapping. Nick Ferguson raises his arms to pump up the fans. “You can do it! You can do it!” someone shouts. But I feel more alone and insecure than ever. I pace and shake out my legs, daubing the turf with my right foot, then my left. A whistle blows.

Of all the hundreds upon hundreds of footballs I have booted in the prelude to this kick, of all the hooks and slices and short kicks and weak kicks and slips and mis-hits—including the one two minutes earlier—none has been like this one. In fact, in the long history of the NFL, through the eras of dropkickers and toe kickers and never-seen-a-football European sidewinders, no one—no one—has likely kicked a ball like this one. “OOOOoooooHHHHhhhhh!!!!” the crowd and players cry as one. Amid the noise, I hear a single scream of anguish.

The ball flies high enough and far enough. But it is a line drive to the left of the goalposts. A line drive spiral to the left of the goalposts. A spiral!

I drop to the ground as if I’ve been shot and bury my helmeted forehead in the grass. The horn sounds. While the rest of the team runs past my carcass rotting on the turf, Jason Elam, a broad smile highlighting the crow’s-feet around his bright eyes, helps me up. Mike Leach pats me on the back. A defensive lineman named Demetrin Veal puts an arm around my shoulders and says it’ll be okay. I walk the slow walk of the damned to the sideline with Jason.

Sports psychology tells us that, in demanding situations, we need to shut everything out. But I should have let it in—breathed deeply, to be sure, but embraced my slow-motion moment and inhaled my surroundings: the crowd, the grass, the uniform, the taunting players, the video guys in the tower, the coaches, the scouts, the equipment staff, the fans, the media, the preteen ball boys who are beginning to feel like kids of my own. Instead of embracing my few seconds of panic, I simply panicked.

As I leave the field, I can’t look anyone in the eyes, though I know everyone’s eyes are on me. I feel as if I have let the team down—at 30 minutes per player, my misses cost my teammates a total of 45 hours of freedom—and I let myself down. That I had never before kicked a football from a live snap over an offensive line and a full defense is more excuse than pertinent detail. I wanted to validate my presence here. Instead, I failed publicly and spectacularly.

In the seconds after the debacle, a few Broncos try to help me recover. “Your team is going to need you again,” Jason says. “Don’t go into the tank.” Tight end Stephen Alexander whacks me on the shoulder pads and pats me on the helmet. “Shake it off,” he says. Micah reminds me that everyone wants me to succeed. “You heard the crowd. You heard the team,” he says. “They’ll be cheering for you the next time.” My favorite ball boy, Chandler Smith, the polite and adorable 13-year-old son of assistant strength coach Cedric Smith, comforts me best of all. “Close, Mr. Stefan,” he says, either too young to realize just how badly I have performed or too well raised to say anything different.

I sit on my helmet and wipe sweat from my brow while pretending to watch the rest of practice. I apologize to Micah, who tells me not to. Ronnie Bradford says that, watching me bang 35- and 40-yarders with room to spare in warm-ups, he thought, “This is going to be easy.” Then, as curtain time approached, he saw me tighten. Ted Sundquist says that, in my position, he would have spit the bit, too.

When I regain composure, I rejoin the cluster of players standing behind the yellow rope waiting their turn to play. I sneak up on quarterback Preston Parsons and hide my head in his shoulder pads. “Don’t even talk to me!” he says. Tight end Tony Scheffler says he really wanted that half hour off. ‘‘That was pathetic,” offensive tackle Matt Lepsis offers. Cornell Green, another offensive lineman, wants me to run the quarter-mile penalty he incurred for jumping offside in practice. I tell him I will. “They were going to tape you up and throw you in the cold tub,” he says. ‘‘I’ll tell them not to.”

With Jason Elam, I search for new ways to express my embarrassment and disappointment. I say that I’m dumbfounded by how I could have missed so badly.

“You play long enough in the NFL, you’ll miss some kicks,” Jason says.

“But I’m not playing long enough in the NFL,” I reply.

‘‘That’s what I’m saying. You’ve played long enough to miss some kicks.”

A posse of about 30 reporters and cameramen awaits me as I stroll off the field alone. I handle them with greater ease than I did the kicks. They ask who I am and why I’m here. They ask how it’s been going, and I in turn ask whether they saw me bagging 40-yarders. They want to know if I have any kicking experience. They want to know who’s taken me under his wing. They want to know what the stakes were for my kick. They want to know how it felt. They want to know whether it changed how I appreciate and perceive the NFL. I answer honestly, in sound bites.

From his nearby daily news-conference perch, Shanahan is kind. He tells the throng that I didn’t choke. “What was great about that, since he’s been around, he knows what a kicker has to go through,” my coach says. ‘‘When you miss a kick in a game, you’re by yourself, nobody talks to you for a week until the next game. It was a lot of fun.”

Not for me it wasn’t. But I’m grateful that Shanahan is at least charitable. At the back of the crowd, still in shoulder pads, I pretend to be another reporter. “So will you give that kicker a second chance?” I ask. Shanahan sees that it’s me, flashes one of the tight, white smiles that often cross his permanently windburned face, and says that he will.

Amid a pulsing dance beat, I do a perp walk through the locker room. The reviews are not good. Linebacker Keith Burns: “I was thoroughly disgusted.” Center Tom Nalen: “Thanks for fucking us.” Tackle Chad Mustard: “Shit the bed! Call housecleaning! We need new sheets!” Starting quarterback Jake Plummer: “Don’t fucking come near me. Get out of here.” But when the abuse subsides, the players (the more sympathetic ones, anyway) seize on my failure as a happy confirmation of reality, a big, fat I-told-you-so. My going down in an intergalactic fireball illuminates their struggles to play professional football.

Athletes complain that the reporters who smugly judge their performance and behavior can’t possibly understand what they experience. Before joining the Broncos, I was sympathetic to the Atticus Finch principle, that you can’t judge someone unless you walk around in his shoes. I’d watched and reported on enough sports, and talked to enough jocks, to conclude that fans and reporters often absurdly consider athletes as automatons who should never fail. How could that jerk have missed? (That night, when a local TV sports reporter cracks in his report that my book should be titled Worst Kicker Ever, I say to the screen: “Asshole.”) But, trite as it may sound, now I have learned the lesson because I have lived it. And my teammates love that. A half dozen tell me that I got a taste of their lives, that I should multiply the pressure I felt by 25 or 50 or 100, that I was lucky to have had just a half hour of meetings riding on my performance instead of my future employment.

I skip the ice pool out of fear one of the offensive linemen will drown me and instead walk directly to the showers. Just outside, next to the urinals, fullback Kyle Johnson is wearing a white towel and his Broncos ID, waiting to take a drug test.

“How was that for pressure?” he asks.

“More than anything I’ve felt in my life.”

“That’s what it’s like every play of every game. It’ll keep you up at night—if you let it.”

By the end of lunch, my folly seems forgotten. Either I don’t matter much to my teammates, or, I prefer to think, they understand that there but for the grace of God go they. The coaches may expect perfection. The players understand it’s an impossible standard.

Two days after my debut, FG is on the schedule again. Jake Plummer asks if I’m prepared for redemption—and says the stakes are always higher the second time. But my fellow kickers aren’t concerned with whether I’ll have an encore. It’s just another day at camp for them. Jason regales us with tales of buzzing a herd of antelopes in Colorado in his 1957 de Havilland Beaver airplane. Special teams assistant coach Thomas McGaughey—universally known as T-Mac—notes that Jason would rather be killing antelopes than buzzing them. Todd makes the sound of propeller blades and suggests that Jason could do both at the same time.

I laser the ball from 35 yards on the turf field. T-Mac calls it my best hit yet as a Bronco and announces, “He’s full of piss and vinegar!” I hand him my tape recorder. He hits the red button and talks. “Stefan, do not shit down your leg today. Focus. Don’t be scared. Execute. Swing. If you shit down your leg today, your reps will be limited from here on out.” I line up for another from 35.

“You better get the fucking ball up. Get it up! There it is!” T-Mac shouts, not sarcastically. “Whoa ho ho! He’s on the driving range!” he says in a falsetto.

“Back him up,” Ronnie says. “He’ll hit a forty-yarder.”

“Next on the tee box, from New York City, Stefan Fatsis! Whaaaaaaa …” I make the 40-yarder. I’m completely comfortable. Nervous, yes, but in a good way. After my flop, Jason told me that if you’re not nervous, you don’t care. He said he’s nervous kicking an extra point in a preseason game. We repair to the weight room to count down the time to FG. I pee, eat a chocolate brownie Myoplex protein bar, and read the Denver Post. With 10 minutes to go, I make two kicks from 30 on grass and patrol the sideline calmly, stretching my legs and breathing methodically. Paul writes in my notebook: “Looks much better today. More relaxed.” Instead of standing alone to await my fate, I stick close by Micah while he ingathers snaps from Mike Leach. Snapper, holder, and kicker are a unit, after all.

“Field goal and field-goal rush!” Shanahan shouts. “Let’s go!” Jason again converts all 10 kicks from the same distances and locations as the other day. The last ball skims the right upright and bounces through. I watch with stupefied awe, but no intimidation or worry. I’m not shaking or hyperventilating, and I’m not afraid.

“Offense!” Shanahan barks. “Fifty-yard line!” The horn sounds. Redemption will have to wait. “At least you were ready,” Paul says.

From A Few Seconds of Panic by Stefan Fatsis. Published by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright © 2008 by Stefan Fatsis.

SIDEBAR

Q&A with Stefan Fatsis

In Word Freak [“Man of Letters,” Sept|Oct 2001] Stefan Fatsis C’85 explored the history and obscure subculture surrounding the iconic board game Scrabble, training himself to be an expert player along the way. His new book, A Few Seconds of Panic, tells how this “5-foot-8, 170-pound, 43-year-old sportswriter,” as the subtitle puts it, managed to talk his way onto the Denver Broncos roster as a kicker during the team’s 2006 training camp and preseason and what he learned about the subculture—hardly unknown but little understood—of the modern NFL.

While he didn’t exactly become an expert this time (see the accompanying excerpt), he did learn something about what it’s like to be a player—which, given the personal stats listed above, is still pretty impressive—and gain both the trust and the respect of his teammates. This summer, as he was engaged in the somewhat less physically taxing demands of a book tour, Fatsis took time out for an interview with Gazette editor John Prendergast.

Why do this? Just a natural followup to the Scrabble book?

Strangely, yes. Becoming an expert Scrabble player challenged my mind. I wanted to do another piece of participatory journalism that challenged my body (before it’s too late). But as with Word Freak there had to be a larger story about a mysterious American subculture. That may seem an odd thing to say about professional football, which is covered voraciously by a 24/7 media machine. But I’d long believed that the wall between reporters and players had grown so tall and so thick that the public didn’t—couldn’t—get an honest depiction of life inside the sport. The only way to do that, I believed, was to play, and the only act I felt I could perform on a field even remotely credibly compared to the pros was kicking field goals.

How did your family feel about it? Were they concerned for your safety and/or sanity?

The reality of what I was proposing didn’t dawn on my wife, Melissa Block [host of National Public Radio’s All Things Considered], until after a colleague of hers jokingly asked whether I had a good life-insurance policy. I assured her—translation: I lied—that there was no chance anyone would try to tackle me. But Melissa never doubted my sanity because journalistically it seemed like a good idea. Plus, our then-four-year-old daughter liked telling people that I was playing for the Broncos.

There’s certainly a fair amount of humor in the book, but it’s not a lark. You took the training very seriously. Can you talk a little about that?

I did take the physical part seriously. I found a trainer in Washington, D.C., where we live, who worked with professional athletes. Over the course of about 15 months, I ran and lifted weights and ate six meals a day and grew from about 160 to 172 pounds. I was in by far the best shape of my life. At the same time, through the magic of Google, I found a kicking coach, a record-setting college kicker—and failed NFL kicker—named Paul Woodside. Paul was my age and embraced me and my quest without a single doubt. He wanted me to do well and believed I could do well—for him and for every athlete who dreamed about playing in the NFL.

How much of your approach came out of your own desire and how much from trying to distinguish what you were doing from what George Plimpton did in the 1960s with Paper Lion?

My own desire first. I played soccer in high school, in intramurals at Penn (I attended one tryout for the JV, realized I was out of my league and went straight to the DP) and in adult leagues. So I knew I could kick a ball. Plus, I’m fairly competitive. So I wanted to do well. Plimpton, as he described it, joined the Detroit Lions in the summer of 1963 unprepared. His stated goal was to find out “how one got along” if thrust into the company of professionals. Today, we know the answer: He’d be squashed. So I needed to twist the Plimptonian proposition. I needed to try. I didn’t want to just show up in Denver with a notebook.

Do you think your attitude helped you gain acceptance among the players?

Absolutely. There was never a doubt that I wasn’t an “actual player,” as a Broncos quarterback put it. Nor did I harbor any fantasies of becoming one. But it was clear to my teammates that I understood the mechanics of kicking, that I had practiced a lot and, most important, that I was committed to working hard and getting better. One book reviewer accused me of “dreamy self-glorification,” which I found pretty funny. Because my experience was largely about self-humiliation, and in the telling about self-deprecation. I wanted to do well, absolutely, but that’s a natural athletic and competitive drive. And I believed that the only way to understand pro sports and to get the players to open up to me—to talk in ways that they don’t normally talk to reporters—was to demonstrate that I was serious—not good, necessarily, but serious.

There’s a great moment near the end of the book when the owner of another team sees you with the players and asks if you’re a Broncos fan and you reply that no, you’re a Bronco. What did you learn about the NFL as a player that you couldn’t learn as a reporter?

That same book reviewer asserted that I wasn’t a Bronco because I couldn’t experience being cut—because I had a non-football life to return to after training camp. No kidding. But I know that I felt more like a part of the team than like a reporter covering the team. And I’m convinced that allowed me to tell a story I wouldn’t have been able to tell otherwise. I think there are too many artificial barriers in journalism. By breaking down this one—by being a person first and eventually a teammate, rather than a questions-asking reporter, by being there all day every day—I gained otherwise unobtainable insight. I developed friendships with players, coaches, front-office executives, the team owner, the equipment guys, the groundskeeper, the p.r. staffers. That didn’t compromise my journalistic “objectivity.” It simply allowed me to tell a more complete story.

As a player, I was able to examine up close the complexity of pro football. I was able to experience the pressure of athletic performance and the monotony, drudgery, and exhaustion of training camp. I was able to witness the psychological, physical and emotional toll of this painful, Darwinian sport. I got to see the private interactions between players and coaches, players and management, and players and players. And I got to hear—during long, brutally honest conversations—just how thoughtful and introspective many players are about their profession. They’re not dumb jocks. They question the sanity of the tradeoff they make: the impossibly pressure-filled workplace, the total absence of job security, the ever-present threat of temporary or permanent injury in exchange for the exhilarating thrill of competition and the long shot of the multimillion-dollar payday.

Did the book turn out the way you thought it would? If not, how did it change in the telling?

Well, I thought I’d be nailing 50-yard field goals—honestly. So while I did make some 40-yarders—nothing to sneeze at; 40 yards is a long way—I didn’t get as good on the field as I’d hoped, which was sad to me. But the book was never intended to be about my middle-aged kicking adventures. It was about infiltrating the skunk works of the NFL. Thanks to the candor of the Broncos players and the openness of Broncos management, I think the book turned out to be even more revealing than I’d originally hoped.

Although you got to kick in practice with the Broncos, the NFL wouldn’t let you kick in an actual preseason game. How disappointing was that?

In the moment, it was frustrating, because the reason for barring me felt specious. The NFL said that allowing an amateur to play in a preseason game could undermine the league’s integrity. I argued that kicking a short field goal or an extra point in the fourth quarter of an utterly meaningless preseason game would have been harmless and in fact entertaining. Plus, it wasn’t as if I’d just showed up one day to kick; I’d been through camp! As terrifying as the reality of lining up against a team of players who didn’t know me would have been, I would have done it in a second. Broncos owner Pat Bowlen and head coach Mike Shanahan were willing to let me, and my teammates would have loved to see me try.

In the end, though, it didn’t matter. As I said, this wasn’t fantasy camp. I didn’t need to play in a real game to complete the narrative. In fact, I think it might have distracted from the point of the book because kicking in a real game would have been a typical sportswriterly way of judging my experience, and a particularly sportswriterly climax to the story, too. In the movie, though, I’d be happy to see the credits roll after I kick a last-second, 50-yard game-winner.

In the book, you’re 43. You’re a couple of years older now. Still in shape?

Not the same kind of shape. Though I did kick some footballs with Scott Simon of NPR the other day. I blasted a 35-yarder into the netting beyond the uprights. Alas, no other NFL team has called.