Class of ’95 | Few companies have more palpably influenced American life than Bethlehem Steel. For nearly a century and a half, the giant company’s factories churned out everything from I-beams to artillery, and it’s no exaggeration to say that the things it made helped pioneer the skyscraper and win two world wars. Although defunct since the 1990s, much of its Lehigh Valley plant still anchors the eastern edge of what has come to be called the Rust Belt. Lately however, machines and workers have returned to the once-powerful company’s former electric repair shop, for it’s in this building that the much-anticipated National Museum of Industrial History was set to open its doors to the public last month.

The museum’s first president and CEO is Amy Hollander GFA’95, and she and her colleagues have been working for many months to ensure that it opens on schedule. When we spoke to her in June, Hollander said she had been “developing procedures and policies, bringing on an exhibit design team, and coordinating to renovate the building, which dates from 1913.

“We’re very sensitive about the work being done to it and are making sure that the building itself is treated as the artifact it is, and I’ve also gotten many of the large exhibits installed,” she added. “It’s been a pretty amazing effort, and through it all, every time we’ve needed anything, our neighbors have been stepping in to offer help.”

The museum is actually just one component of a sweeping redevelopment scheme that already includes a casino, a public-television station, and a performing-arts center.

“People are very excited,” Hollander remarked. “Bethlehem Steel decided to take this site, to preserve it for the future by cleaning it up; it’s an incredible example of private, public, and nonprofit all partnering to develop these 1,800 acres.”

The idea of a museum devoted to America’s industrial past first materialized in the late 1990s, and many former Bethlehem Steel executives lent their support to the project. It was around this time as well that the embryonic museum forged a crucial relationship with the Smithsonian Institution, becoming the first of more than 200 official affiliates of the institution through a program established in 1996.

“This partnership allows us to borrow artifacts from the Smithsonian and also to have access to their experts,” said Hollander. “Our museum is also unique in the affiliate program in that most have only one or two artifacts, but we have over 20.”

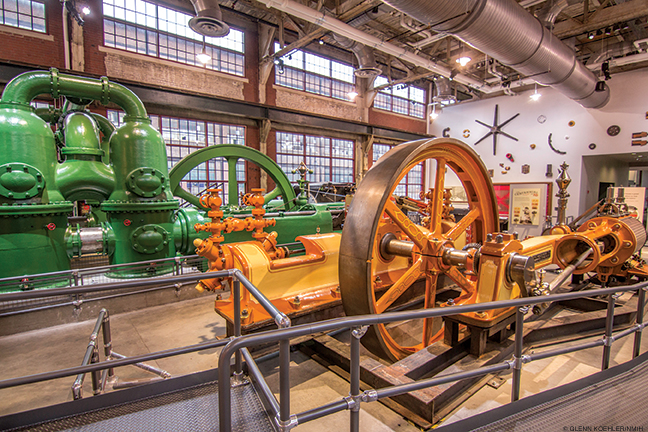

Among them are the Otto Silent Engine, the oldest surviving American four-cycle engine, once used to power Princeton’s observatory dome; the Nasmyth Steam Hammer, one of the first in America, used to make railway car parts by the Union Iron Works in High Bridge, New Jersey; and the Linde-Wolf ammonia compressor, the oldest surviving refrigeration compressor, which allowed the American Brewery in Baltimore to increase its output from 40,000 to 100,000 barrels of beer a year.

Many of the loaned pieces were featured in an exhibition at the Arts and Industries Building in Washington during the 1976 Bicentennial celebration. Part of the intent behind that exhibition was to pay homage to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia a century before—a watershed moment in American history that Hollander hopes her museum will inspire visitors to think about.

“The Centennial Exposition was the first official world’s fair on our soil,” she observed. “It was America’s industrial debut on the world stage, and a pivotal point in the way other countries perceived America. A real transformation was occurring from an agrarian to an industrial society, and visitors from 37 nations went back and reported on what they saw. It struck them as massive in scale, a country with seemingly unlimited natural resources, and they saw a level of ingenuity that said America was on the rise and that if other countries didn’t start innovating that they would fall behind very quickly. So a lot of these really beautiful pieces allow us to talk about that particular takeaway.”

In designing the exhibits, Hollander and her staff made a concerted effort to immerse the visitor in the world of America’s industrial past.

“The artifacts are balanced by a variety of interactive experiences, because we felt it was very important to convey a sense of real people and real peoples’ stories,” she remarked. Video installations, for instance, allow visitors to watch archival footage of machines in action—in some cases machines similar to those on display, and in others things that simply couldn’t fit into the galleries, like a blast furnace or a gigantic hammer used to manipulate steel. In addition, an oral-history phone system brings the voices of American industry to life.

“You can listen to stories of workers, of entrepreneurs, of union leaders, of inventors,” said Hollander. “That runs throughout the whole museum and ends with the ability to hear from the people who were responsible for transforming this site, from Bethlehem Steel, to the mayor, the governor—all the different people who worked together to build this incredibly thriving community center.” Also on display will be the collection of Homer Laboratories, Bethlehem Steel’s former research and development department, which comprises a group of operable scale models of every machine once needed to produce steel in the company’s plant.

For Hollander herself, it all began with a barn-raising she attended at the invitation of a mentor. Fresh from an undergraduate program in art history, she had assumed a career in art museums awaited her, only to start having second thoughts.

“I had come to realize that I was much more of a hands-on educator,” she reflected, “and that I was much more interested in the time periods of the paintings than the paintings themselves—why they looked the way they did based on what was happening in the culture, and how that changed style and technique.” Watching the post-and-beam frame of the barn take shape captured her imagination in a way that art history hadn’t.

“I decided to pursue historic preservation because I’d become fascinated with the concept of how traditional craftsmanship had changed, and how important it was for people to understand those kinds of developments,” she said. “So I took two classes at Penn as a non-matriculated student, then applied and fell in love with historic preservation. It’s not in any way surprising to me that the classes that I took are still very much alive in my day-to-day work.”

After getting her degree, she went on to do consulting and curatorial work, then to directorships at the Readington Museums and the Red Mill Museum, both in New Jersey. Finally, in early May of this year, she arrived in Bethlehem.

Although a museum of industrial history is by definition about what once was, Hollander is equally focused on the future, and hopes that some of tomorrow’s innovators will be among the 50,000 people who are projected to visit in the first year alone.

“Our mission is pretty simple—to forge a connection between America’s industrial past to today, by educating the public and inspiring the visionaries of tomorrow,” she said. “So every time something new goes up after having this empty shell of a building, I just get a big smile on my face—because I can see what could only be imagined before, and can see the impact it’s going to make. I’ve actually had kids come through now and I see their eyes light up, and that’s how I know we’re moving in the right direction.”

—David Perrelli C’01

Preservation of our history is vital to educate our future citizens and intrigue the young to

Implement their ideas and inventions.