A Franco-American worries that he’s not quite French enough.

By Maxime McKenna

Frank has been getting by on an Esperanto of his own making, an amalgamation of Romance language stereotypes effective enough for ordering food and beer. “You speak French, that’s so cool,” he pants at me as we climb the hill of Montmartre, our sweatshirts zipped and trousers long. It is always mild, pleasant walking weather whenever I come to France, and this summer is no exception. “That’s so … useful,” he says. He heard me checking in at the hostel and immediately suggested we go out for a drink. We also wrangled up Ryan, whose French is little more than a guttural extension of his Spanish. The bar we’re going to comes highly recommended by a blog Frank’s been following.

It’s also the kind of place where my talent means nil. Frank comes back with a round and a couple of planches, the wooden boards draped in cheese and charcuterie that constitute French pub grub. “Tres cervezas y tres plan-chess, s’il vous please und mercy, bucko!” goes the linguistic butchery that acquired our dinners. It scarcely matters: everyone at this place is young, hip, and English-speaking.

For the last five years, my annual trip to France, in addition to being a vacation and a family reunion, has been a project of self-edification. Before, I took my French heritage, language, and nationality for granted. But young adulthood, with the dual pressure of careerism and identity-building, cast doubts. I had always been French, but how French was I? Certainly, I couldn’t carry on a college-level discourse in French. Nor could I write this essay. Why wasn’t I more French?

Whenever I fail to “pass” completely, I never hesitate to hyphenate. I’m not American; I’m Franco-American. If having a French mother and more than half of my extended family in France has not given me a flawless accent or cultural fluency, it has at least granted me the use of that prefix.

My Frenchness has been an indispensible factor in promoting myself to universities, graduate schools, and employers. But I fear that the rusty language skills that actually prop it up could atrophy beyond rescue. This has spurred a personal French revival. The summer after high school, I brought a friend to Paris and showed her the city with all the panache of a Parisian. See? I am French. Of course, maps were consulted in private and mistakes retroactively masked with intention. Montmartre is bloated with tourists, anyway. We’re much better off in Montparnasse. We can visit Sartre’s grave! Such are the pitfalls of the hyphen.

Now I put Franco- to the test. With each trip, I try to elevate the conversation with friends and family. I dig myself deep into French current events, try to engage with as many French people as possible, and skirt the more popular and frequented locales. Movie theaters, unassuming cafés, and parks in residential neighborhoods take the place of the Louvre, Notre-Dame, and the Champs-Élysées.

This summer I made a point of going to flea markets in the banlieue, where I haggled with an elderly Frenchman over neckties from now-shuttered department stores. It went so well that, at least in that moment, I was Franco-nothing but instead full-fledged French. If only I could spend enough time in France, I could do away with self-examination altogether, and with it that hyphen.

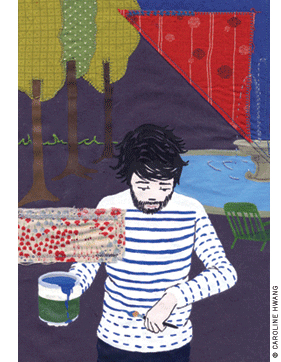

To wage the fight on the homefront, I came into possession of an accordion. Fulfilling a stereotype, sure. But claiming a heritage is tricky. For my American friends, I couldn’t be French unless I enjoyed foie grasand owned at least one striped shirt.

So my outing with Frank and Ryan was to be another test. Compared to them, I was Charles de Gaulle born on the Fourteenth of July. But could I still pass for French in the company of such blatant Americans—twentysomething beer-drinkers whose style and behavior could betray my split cultural heritage at any moment?

This question became irrelevant.

“Qu’es-ce que tu veux?” a shaggy bartender asked as I approached him for the second round, and without realizing it I answered his informal query with the formal vous. This is part instinctive and part self-conditioned, following an episode five years before when, basking in pride at having talked a street merchant down to cost in my secondary language (for a kitschy umbrella hat, properly emblazoned with the Eiffel Tower), I realized I had referred to him the whole time in the informal tu. Mortified by my unintentional condescension, I had resolved to beat the vous–tu distinction deep into my brain.

Back at our table, I flushed with embarrassed epiphany. I must have seemed so stiff. Sure, my mother would never have reciprocally tutoyer’d the bartender, had he been so brash to address her that way. But we were peers, or at least that’s the impression I sought to give. With my s’il vous plait’s and merci, monsieur’s I betrayed something more like a systematic rehearsal of the language than seamless fluency.

It turns out that Frank, with his Babel-babble, was onto something new. I expected people in the bar to be cosmopolitan, switching between instinctive French and practical English. Instead, they were speaking French but doing away with honorifics. English flattened the formal and informal registers long ago—losing the thee and thou you only ever see now in the King James Bible—but the distinction is still second-nature for speakers of many other languages.

Where had this register-neutral French come from? And how common was it? Now I was faced with a new problem and with it a fresh arsenal of personal tests. You might have an incredible vocabulary and command of grammar, but you’re not fluent in a language until you’re fluent in how, when, and where to use it. I was stymied all over again. I would never overcome the hyphen.

Two o’clock, the morning after Bastille Day, and I’m walking back to the hostel after fighting for hours through the congested Metro. With the rest of Greater Paris, I had been down to the Champ de Mars for the free rock concert and Eiffel Tower fireworks.

All the best vantages had been claimed since the morning, but by the creative use of transit, plenty of excusez-moi’s, and some strategic but forgivable rudeness, I scored a spot on the lawn with a view of the stage. Johnny Hallyday, France’s iconic answer to Elvis, was singing Bob Seger in translation. This is akin to Tina Turner singing Edith Piaf on America’s Independence Day. And when Piaf herself made an appearance, it was in a remix sound-collage.

So there was the truth of the matter: I wasn’t the only one with hyphen anxiety. It runs all the way through modern France. In America, the trope of the “melting pot” allows us to celebrate the country’s singularity even as we honor the plurality of her cultural makeup. The French, on the other hand, must embrace the cultural mishmash that is the globalized new world order. Their most nationalistic day becomes the most internationalistic. A DJ can hyphenate Piaf with African rhythms and no one flinches. The quintessentially French Johnny Hallyday can derive from the quintessentially American Elvis Presley and it somehow makes sense. What else would you expect when the crowd itself brims with people from all over the world, who came to Paris to witness a spectacle honoring a country they don’t even belong to?

Meanwhile, barhopping young citoyens speak degraded versions of both French and English, and are no less French for it. There are still people who scratch out Coca-cola from café menu boards and slam Nike-wearing city kids, but by and large they live in rural areas. The other end of the French hipness continuum embraces cosmopolitanism—not only accepting English’s victory over French as the world language, but appropriating American slang and habits. Miami crime dramas are the new cowboy comics, and there have to be more McDo’s in Paris than in any city Stateside. I straddle these two aesthetics, and suspect most French people do as well.

I may want to transform Franco-American into Americo-French and finally into just plain French. But American-ness and Frenchness are harder than ever to define. Figuring out just what these designations mean may turn out to be the greatest challenge.

Maxime McKenna is a College senior from Cape May, New Jersey.