Can I renounce speech, and almost everything else, for three months?

By Steven Schwartzberg

I’m sitting at a picnic table behind the institutional but stately brick building that houses the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. It’s the last day of summer, and glorious. Blue sky, the air warm and hinting at humidity, even a tad sultry. I’m staring into a thick forest that skirts the property. I can see the forest’s edge, but not what lies just a bit deeper within.

For the 60-odd people gathered here, it’s not just the end of summer. It’s the last day of many things. Soon we will enter into the protracted agonies, delights, monotony, and strangeness of a long communal silence. For three months—from now until just days before the winter solstice—my daily routine will be to awaken (early) and spend every day, all day, in alternating periods of sitting and walking meditation.

Whoa, three months! Remind me: I chose this, right?

Choice seems the closest word, but it doesn’t quite fit. As with many of the large and often unexpected decisions I’ve made in the past few years, this one registered internally as a surprise, more like receiving news than generating it. I awoke one morning and heard myself think, “Huh! I’m going to do a three-month retreat.” As if it were already determined, as if I’d received a terse memorandum from my boss. It was like having your partner announce, “I’ve decided: We’re moving to Zimbabwe.” My follow-up thoughts were, “Really? Are you sure? Can’t we talk about this?”

Of course I could have ignored the urging, or deferred it until it shrank away. But big life decisions are a curious mix of the logical and the preposterous, of steering and getting out of one’s own way, of initiation and surrender. And so now here I was, relishing this last day of summer. Wistful. Excited. Freaked out.

And quite pleased with myself. A kind of how-cool-am-I pleased, a look-who’s-a-serious-Buddhist pleased. Which seems particularly absurd, given that Buddhism’s path to liberation is grounded in the belief that the self is delusion, and that feeding the ego is a basic cause of suffering.

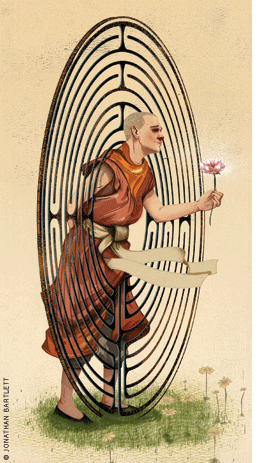

How abundant, the opportunities to revisit that lesson! The night before arriving here, I gathered some friends for an informal ritual of support and camaraderie, a bon voyage before sailing solo into the waters of my own restless mind. The highlight of the ritual came when a friend ceremonially cut my hair monk-short (a style easily abetted by my particular pattern of middle-aged balding, which leaves me with a medieval clerical tonsure even in these most secular of times). This symbolic shearing was meant to buzz me into anonymity and thus ease the entry into my period of temporary monasticism. But here, too, attempts at Buddha-like detachment were counterproductive. I thought the haircut looked kind of hot. It made me feel more attractive, not more neutered.

Plus, to my dismay, when I arrived, I saw that several other men and women had also shorn their hair—shorter and (so I speculated) with less egotistical flair than I had. And probably none had been pretentious enough to invite 12 friends over to witness it. Can three months even begin to dent the depth of my self-absorption?

I stroll around the property and chat with several others who will be part of our community, our sangha. I’m curious about who else is drawn to this period of rigorous meditation and renunciation, of willful withdrawal from the myriad distractions, stimulations, compulsions, and joys of ordinary life. Who else is devoted—or, as my 97-year-old grandmother suggested, nutty—enough to give up talking, reading, music, sex, the Internet, friends, lovers, the gym, sex, alcohol, world news, shopping, hobbies, sex, and television (and oh, have I mentioned sex)?

It’s not that these activities are intrinsically bad. They offer meaning, diversion, relief, and solace. It’s more that we are so subsumed by our habits and routines, so lost, we never have the possibility of coming to see who we are, and how the mind works, without them. Maybe if we can see, or even just glimpse, how the mind works away from these continually muddying waters, we can awaken to a deeper freedom—from the seductive but untrue stories we habitually tell ourselves, from delusions that only seem “real” because the knot of daily life is too thick to disentangle them, from the constant but inadvertent perpetuation of our own suffering.

And so I meet Ted, a friendly, 40-something man with an easy manner and hair shorter than mine (not that I’m fixated or anything). It’s hard not to notice, quickly, the word SLAVE tattooed on his arm. I ask, and he explains: “It’s about alcohol and drugs. I used to be a slave to alcohol. Now I’m a slave to the tattoo.” He says his drug addiction started in his teens, and for decades nothing helped: 12-step programs, inpatient hospitalizations, detox, long-term residential treatments, halfway houses. Nothing got him sober except Buddhism. Meditation had kept him clean now for four years, without one slip.

I also meet Lenny, whose life oddly parallels mine: middle-aged psychologist closes his psychotherapy practice, gives up his home, begins a new life as a spiritually eclectic nomad. And I chat with Lindsay, a bright-eyed, fervent 25-year-old here on her first retreat, deeply enamored of Jesus and encouraged to make this journey into silence by her shrink, a woman who happens also to be a rabbi. What a great image for the spiritual mixings we’ve come to take for granted in the West: a female rabbi—itself heretical just a few decades ago—interested enough in Buddhist meditation to recommend it to her young Christian client.

It’s early evening. Soon we will enter the meditation hall, take our precepts, and officially commence the retreat. I feel a sudden twinge of anxiety, a last-minute bout of loneliness and self-pity. I recall the mildly renegade escape options that had crossed my mind during the day. I could have easily skipped out for one final swim at my favorite swimming hole, not much more than an hour away, a haven since my days at graduate school. I could have driven to Wal-Mart for a small rug to brighten my cell-like monastic room. I have three months free—I could have bought a plane ticket to, I don’t know, Zimbabwe? That I fall prey to none of these 11th-hour indulgences, I take as an encouraging sign.

I linger on the front veranda of the building. The sunset, the last of summer, is multi-hued and soft, the enveloping forest now an indistinct blur. A few isolated trees have already started their flamboyant coloring. Soon they will all be denuded. Winter will come. Everything changes; all is impermanent. It is said that being able to live this one simple truth—not just think it, not just brush by it, but actually live it—is all that is needed to awaken.

I observe some of the other participants. Several are scurrying into last-minute conversations. An attractive middle-aged woman stands with a few others, listening to words I cannot hear. She is rubbing her freshly shaved head unconsciously, disbelievingly. She is smiling. I realize that I, too, am eager for an irrelevant conversation. With anyone. The words don’t matter as much as the underlying yearning: Notice me. Reassure me.

And I recall why I am here: To know more deeply, to get it into my bones, the folly of fearing my own mind.

This silence, the lack of distractions, the multiple renunciations: It all terrifies me. How will I avoid my capacity for worry, my sorrows, the relentless edge of my judgments? Where can I hide from my own failures, my fears of dying, my fears of living?

No escape from myself. This is the last place I want to be, and that’s why I’m here. I do not want to live in selective, distant acquaintanceship with myself. Or, by extension, with life. This experiment in withdrawal is not a way out but a way in.

I enter the hall. For 30 minutes our new sangha meditates together. Then, in a low-key and unpretentious ceremony, we chant in Pali, the language of the Buddha, the ancient precepts of temporary monastics. The language is strange yet comforting; the threshold I am crossing profound, and matter-of-fact.

My season of silence has begun.

Steven Schwartzberg C’80 spent autumn 2007 in silence, practicing Vipassana meditation. He reports that it was an eye-opening, mind-expanding journey that still echoes gently in his life. It may even have begun to dent—just dent—his self-absorption. He can be reached at [email protected].